New York Film Festival 2009

Welcome to the Festival Coverage thread for the 47th New York Film Festival, fall 2009, put on by the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

ANDRE DUSOLLIER IN RESNAIS' WILD REEDS

(OPENING NIGHT FILM NYFF 2009)

The full schedule of public screenings with thumbnail descriptions of the 28 official selection films will be found on the Film Society of Lincoln Center's website here. Press and industry screenings begin September 16.

The FilmLeaf open comments thread for the NYFF is here, starting with the list of films. Below are links to the Festival Coverage thread reviews.

INDEX OF LINKS TO REVIEWS

Antichrist (Lars von Trier 2009)

Around a Small Mountain (Jacques Rivette 2009)

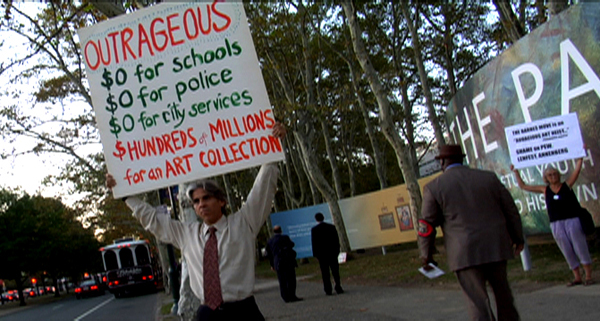

Art of the Steal, The (Don Argott 2009)

Bluebeard (Catherine Breillat 2009)

Broken Embraces (Pedro Almodóvar 2009)

Crossroads of Youth (An Jong-hwa 1934)

Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl 2009)

Everyone Else (Maren Ade 2009)

Ghost Town (Zhao Dayong 2009)

Hadewijch (Bruno Dumont 2009)

Henri-Georges Clouzot's 'Inferno' (Bomberg, Medea 2009)

Independencia (Raya Martin 2009)

Kanikosen (Sabu 2009)

Lebanon (Samuel Maoz 2009)

Life During Wartime (Todd Solondz 2009)

Min Ye; Tell Me... (Soulaymane Cisse 2009)

Mother (Bong Joon-ho 2009)

Mummy, The (Shadi Abdel Salam 1969)

Ne Change Rien (Pedro Costa 2009)

Pier Paolo Pasolini The Rage of Pasolinii (Pasolini, Bertolucci, 1963, 2008)

Police, Adjective (Porumboliu (2009)

Precious (Lee Daniels 2009)

Room and a Half (Khrzharnovsky 2009)

Sweetgrass (Barbash, Taylor 2009)

Sweet Rush (Andrzej Wajda 2009)

To Die As a Man (Rodrigues 2009)

Trash Humpers (Harmony Korine 2009)

Vincere (Marco Bellocchio 2009)

White Material (Claire Denis 2009)

White Ribbon, The (Michael Haneke 2009)

Wild Grass (Alain Resnais 2009)

PENELOPE CRUZ IN ALMODOVAR'S BROKEN EMBRACES

(CLOSING NIGHT FILM NYFF 2009)

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks