-

Newton i. Aduaka: Ezra (2007)

NEWTON I. ADUAKA: EZRA (2007)

MAMOUDU TURAY KAMARA AND OTHERS

A flawed drama of boy soldiers in Africa

Mamoudu Turay Kamara is brooding, charismatic and stylish as Ezra, a sixteen-year-old trained killing machine who has escaped from "The Brotherhood," the rebel army in what is obviously Sierra Leone, though not named here. He is an innocent boy of nine in a prologue when the rebels overrun his school and kidnap him. Ezra is a Sierra Leone civil war story told, unlike Edward Zwick's effective but Euro-centric Blood Diamond, entirely from the African point of view and with Africans in all the main roles. The director is a Nigerian who lives in the UK.

In the frame-story of the film, Ezra stands before a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (on the South African pattern) headed by American Mac Mondale (Richard Gant) and his sister Onitcha (Mariame N'Diaye), though she has had her tongue cut out, bears witness that he was present in an attack on the family village in which their own parents were killed and may even have been the one who killed them. Before such attacks, including this one, the boy soldiers are injected by their superiors with amphetamines, so they can fight for four days, killing heedlessly, in a state of wild excitement and with no shred of a moral sense. After two days if they don't eat, Ezra says, they hallucinate and see demons all around them. After many such experiences the boys develop protective amnesia. The Commission isn't a trial, but Mac Mondale wants Ezra to confess to crimes. He won't. He denies any memory of them.

In its opening passage about the young kidnapped Ezra the film sketches in how the new recruits are indoctrinated, motivated by fear, and brainwashed to forget their families and live for the cause, worshiping their AK-47's. "No hand, no vote" was the rule of the raids: villagers' hands were cut off to frighten them from voting. Ezra has plenty of trauma, but this atrocity is depicted more graphically in Blood Diamond. A surprise and shock: to find that there are girl soldiers too. One Ezra meets up with, Mariam (Mamusu Kallon), becomes the mother of his child. While he can't remember how to read, she comes from a Maoist intellectual journalist father and joined up out of conviction.

Ezra eventually leaves "the Brotherhood" with others, including Mariam, in protest because they are not being fed properly. We also get glimpses of the subject of Blood Diamond, the whites who trade weapons and also drugs for diamonds, the glittering but tainted fruits of this warfare.

It's important to have this material in a film with authentic settings and actors and from the boy soldier's point of view. The film points out at the end that there are about 300,000 child soldiers fighting on the globe, 120,000 of them in Africa.

This film has a convincing look, but it's marred by very serious flaws. The framework of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is its first undoing, because it leads the screenplay into a chaotic series of flashbacks whose chronology is impossible to follow; some reviewers have commented that their order is as blasted as Ezra's drug-addled and traumatized mind. And in the switching back and forth between the flashbacks and the Commission proceedings, the latter are increasingly overwhelmed by the war drama and begin to seem anticlimactic.

The chronology of the various flashbacks becomes even more confusing as Ezra's escape from the Brotherhood gets mixed in with his earlier service, and the rhythm of the story is hobbled. This is one reason why things are confusing. Equally damaging to the natural flow is the fact that all characters speak English rather than whatever they might actually have spoken in individual scenes (Sierra Leone's official language is English but there are 24 native tongues). And to make things worse the voices are post-dubbed, so they're noticeably out of sink. Even Mamoudu Turay Kamara often delivers his English lines in a stilted manner, and you can see the mouths moving before the voices come out. In a few scenes the dialogue is barely comprehensible.

Given how sketchy the story becomes in this treatment, it would be better to read one of several books on the subject of boy soldiers in Africa, notably Ismael Beah's A Long Way Gone: Memories of a Boy Soldier (Feb. 2007), which presents the experience eloquently and in more detail, though even Beah's memories are not always completely reliable, for the same reason that Ezra's are absent: protective amnesia and damaged recall due to drugs and stress.

Ezra was introduced at Sundance 15 months ago where it was nominated for the Grand Jury prize, received several awards in Africa, and has been in limited US release since February. Given this chronology and the film's inherent weaknesses, its inclusion in SFIFF 2008 is open to question

Seen as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-26-2014 at 02:06 AM.

-

Serge bozon: La france (2007)

SERGE BOZON: LA FRANCE (2007)

PASCAL GREGGORY, SYLVIE TESTUD

Lost souls skirting the field of battle, singing songs

This peculiar musical war movie about a woman disguised as a man in search of her soldier husband in World War I France has the courage of its oddball convictions--or does it? It was disconcerting, at least, to hear from director Bozon that his original intention was a film about Arabs in the French-Algerian war of the Sixties. For a French art film you need public money, he said, and to get that the dialogue has to be in French--so voila!--no Arabs, and the dial was turned back to WWI.

La France is the kind of thing that truly delights some of the most ardent festival attendees: a film that's genuinely weird and original, that comes from left field, is quite sure of itself, and is sustained by some of the best actors in its country of origin, good cinematography, and unusual music used in an unexpected way. To others, this is likely to seem merely remote and inexplicable; a long slog even at only 102 minutes. To me, it evoked memories of Bresson, or the Rohmer of Percival, while still seeming a cluster of missed opportunities. Opening in France last November, it received a respectful critical reception and the occasional rave. It also ran in Lincoln Center's New Directors/New Films series early this year and was singled out for special praise by the Village Voice's Nathan Lee.

Bozon and his scenarist, Axelle Ropert, deserve credit for following their own path in constructing what French reviewer Christine Haas called "a melancholy ballad and a humanistic fable."

Here's the premise: a young woman gets a strange letter from her loving husband at the front: "Stop writing me, you will never see me again." She cuts her hair, binds her breasts and, posing as a seventeen-year-old boy, joins a unit whose members she finds sleeping in a field. Of course they try to get rid of him/her, but "Camille" (Sylvie Testud)--she can use her real name, because it's a boy's as easily as a girl's--each time does something so risky and dramatic (gets shot in the hand, jumps off a bridge) that they have to rescue her and keep her in tow a while longer. Eventually her initiative saves them, and she's accepted, even though the Lieutenant (Pascal Greggory) has declared on her first appearance that he/she has the face of somebody who's "seeking death." The surprise is that the essential unmasking will be not of Camille but of the unit she joins. Guillaume Depardieu comes in for an appropriate cameo at the end looking suitably hopeless, pretty, and shattered.

Good use is made here of Testud's androgyny and Greggory's habitual hangdog look. This scrawny, determined "Camille" really resembles a boy, while the Lieutenant's soft, sad visage hints at something very wrong.

Every so often--and this is what the film will be remembered for--the soldiers take out a bunch of handmade junkyard musical instruments and in unprofessional but harmonized falsettos sing a Sixties-style ballad, which is always from a woman's viewpoint--and has, by intention, absolutely nothing to do with the action. Bozon claims that it's a Hollywood tradition and not purely his avantgardism to make war movies with songs that are anachronistic and not plot-related.

The resulting effect, anyhow, lacks any sense of the actual, without slipping over into a purely conceptual or fantastic framework that might have given the themes of loss, loneliness, failure of nerve, and sexual identity (or whatever all this is about) really free rein. Camille is an interesting character with rich picaresque possibilities that are insufficiently explored. Testud seems to give so much, yet get back so little from the film. Greggory's sick-soul character never develops or changes. The other soldiers never take on real personalities. The essential mechanism of most war movies--the sounds and effects of battle--is absent. Instead, violence comes from an unexpected quarter. The resolution is bitter-sweet.

Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008. It won the Prix Jean Vigo in France for independent spirit and originality of style.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-26-2014 at 02:10 AM.

-

Aditya assarat: Wonderful town (2007)

ADITYA ASSARAT: WONDERFUL TOWN (2007)

ANCHALEE SAISOONTORN

In the land of the tsunami, love and menace

Fledgling Thai director Aditya Assarat begins the stunning Wonderful Town with flat, screen-filling images of gentle waves that introduce the locale of southern Thailand hit hard by the 2004 tsunami. This opening heralds the film's strong visual sense as well as a prevailing serenity that is not without edges of menace as time goes on. Convincing performances and lovely visuals serve a subtle, haunting screenplay and the whole shows a strong narrative sense that pays off with the cumulative power of the finale.

This is the story of a young man and woman who come together in a kind of limbo. Their personal stories emerge in bits and pieces as a romance develops between Ton and Na. Ton (Supphasit Kansen) is an architect who comes from Bangkok and stays at a very ordinary hotel where he meets Na (Anchalee Saisoontorn), who seems a clerk and maid, but emerges as the sole member of the owner family who is present to run the place. Ton's work is on a project nearby where luxury resort buildings are under construction near unrestored, perhaps haunted relics of the storm damage. He's volunteered to be here to please the client and in effect just spend a peaceful two months away from the noise of the capital doing not very much. The setting itself, the tsunami town of Takua Pa, is the inspiration for the film.

Ton is interested in Na right away, as he openly reveals when he goes out on a rooftop to help her fold up laundry. He's not so much flirtatious as open and relaxed in a way that shows he wants to be with her. Na is reserved but receptive. A scene where she listens to him singing in the shower shows she's interested too. They go on a little "date," they kiss, they walk together here and there.

There aren't many people around: an older man and woman who work at the hotel; then after a while Wit (Dul Yaambunying) appears, a dicey individual who might be an estranged husband (he's moved out; she asks him to come back), but turns out to be Na's brother, a self-declared reprobate who won't come to help run the hotel.

The romance between Ton and Na is marked by beauty and delicacy. The whole locale seems a place of openness and quiet, despite the noise of the construction site, which Ton has to drive back and forth to. Ton's personal ease is underlined by his tendency to break into little songs. He turns out to have had an earlier life as a musician and his father so disapproved that for five years they've been out of touch.

There's disapproval closer at hand. Four boys on loud motorcycles who circle around and around are the first powerful sign of threat; they're like Cocteau's avenging angels or the hot-rodders in Manuel Pradal's Marie baie des anges. Now Na's warning to Ton that this is a small place and they need to be circumspect makes sense. From then on every scene effortlessly communicates its hints of hostility, perhaps serious danger.

Assarat makes it all seem so simple. The earlier scenes are flat and undeclarative, with the camera often still. The Director of Photography Umpornpol Yugala provides lovely, soft colors and is equally effective in eye-filling closeups of Na's bare skin as with landscapes with figures in the distance. The tight-lipped dialogue keeps the viewer attentive. Zai Kuning and Koichi Shimizu provide delicate guitar backgrounds that hint at uncertainty as well as fill in a sense of calm. Every moment counts. The sense is of a place that's as much traumatized as it is recovering.

Ton's and Na's back stories are a little mysterious. It's not certain what Ton is planning to do at the end.

Aditya Assarat has produced a remarkable film that promises much for the future. It received awards at Las Palmas and Rotterdam and was part of the New Directors/New Films series at Lincoln Center this spring as were six other SFIFF selections. It opens in Paris May 7,2008.

Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-12-2016 at 01:18 AM.

-

Constantina voulgaris: Valse sentimentale (2007)

CONSTANTINA VOULGARIS: VALSE SENTIMENTALE (2007)

Depressed punk love in Athens in the summertime

Voulgaris' raw, mercurial film about two twenty-somethings falling in love during a hot summer in Athens is perfectly in tune with its subject. Artistic, angst-ridden Stamatis Anastopoulos (Thanos Samaras) and Goth-girl Elektra (Loukia Mihalopoulou) meet cute in a video shop. Since both adore Carrie their first encounter is a clash over who'll get to rent it that evening. Reluctantly, they watch it together, which leads to an exchange of names, addresses, and cell phone numbers and subsequent dates and tentative making out, finally sex. They not only share musical and film tastes but above all for their time in life the most important thing, they both passionately hate the same things, which means most things--including families, summer, and vacations. He reinforces her dislikes. It's okay to feel bad, better to feel bad together. The two of them against the world. It's a good match, if not a smooth ride. Jerky editing and scenes that don't come in when you would think or end when logic requires become a virtue. The film's construction ignores conventional expectations as do Stamatis and Elektra and the people they sometimes hang out with. If the relationship doesn't progress very visibly from scene to scene as Valse Sentimentale unfolds that makes perfect sense too, because these kids don't know if the relationship is on or off from one day to the next.

On one early date, they sit outdoors and talk about the best suicide methods. Stamatis favors drowning, Elektra, pills. The camera drops back and shows they're sitting in a grassy, sun-kissed park on a lovely afternoon. And ironically, both are good-looking. She wears cute outfits that show off her cleavage, mostly black. She's not incapable of smiling. He's not incapable of funny remarks. But the style is dark, as is the look of the film. One day she comes in red: "everything else was dirty," she apologizes. Despite cutoffs, suspenders, and Doc Martens, he's surprisingly straight-looking and wears a Chapklinesque mustache and short, well-trimmed hair. Perhaps he's too insecure to be conventionally hip; he is a loner and given to self-mutilation in moments of inner pain, which come regularly in the little flat where he lives with a wall full of brush drawings and a cat.

Sometimes they talk about music and Elektra has a nameless pal who writes songs. In one typically abrupt scene she's alone with the pal on a rooftop at night as he plays a small electric keyboard and the two of them sing the dark verses at the top of their lungs in joyous nihilism. Later she gives Stamatis a CD and wonders if he'll like it. In the classic youthful search for elective affinities, they're always on tenterhooks about whether the other will like the same drink, the same book, the same song, the way they both liked Carrie. An image of perfect union--Platonic, perhaps?--lurks behind their constant mismatching of mood and taste.

Both are too depressed and insecure and flat-out negative to go into a "relationship"--he handles the word uneasily, as if with tongs--with any confidence that they even know what such a thing is, and yet little by little it happens in the jerky, stop-and-start rhythm of the film--whose irregular cutting echoes the couple's moods and uncertainties. (A blow-job pops in suddenly between one scene and another that follows it. An awkward tongue-tied scene between the pair on a couch is inter-cut with another in which he's tenderly waching her hair in the tub--whether before, after, or never we don't know.)

Anyway he does hesitantly ask her to come to his place to take that "relationship" to "the next level"--to make awkward love, which they both love, but can hardly stand the pleasure of. And then naturally things get messy--on the next level.

A movie has rarely caught the uncertainty of young lovers so well. The relationship is painful, and painfully real and touching. It's also punk and Goth, nihilistic and depressed, and glad to be so. It asks for understanding but never for pity. The two main actors are utterly convincing. Voulgaris comes from a well-known writing and filmmaking family and there are likely to be more good things from her.

This was included in the New Directors/New Films series at Lincoln Center and at least one New York writer called it "the one to beat" while others reviled it for being unspeakably vile looking and self-indulgent. Some films do bring out the worst in people, but really, Valse Sentimentale is fresh, urban, youthful, and truthful.

Seen as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-26-2014 at 02:19 AM.

-

Lance hammer: Ballast (2007)

LANCE HAMMER: BALLAST (2007)

JimMyron Ross[IFC FILMS]

An intense debut shot with love and conviction in the Mississippi Delta

First-time LA-based director Lance Hammer's powerful, naturalistic film seeks to capture what he sees as the prevailing sadness of the Mississippi Delta landscape through its concentrated portrait of a little black family torn by terrible grief and gradually struggling from despair to reconciliation and hope. Ballast begins with a shaky camera shot of a flock of birds flying away across a plain in the Mississippi Delta, then to violent events too fast to grasp completely. A white man, John (Johnny McPhail), comes to the door of a little house to ask Lawrence (Micheal J. Smith Sr.) what's wrong. He won't speak, goes outdoors and a shot rings out. He's shot himself. John calls 911 and Lawrence is rushed to the hospital. For a while this almost looks like an episode of "Cops." The hand-held camera throws the viewer in the heart of all this action with a palpable documetary-style intimacy.

Things cool down a bit as the camera moves over to the house nearby on the same lot where a mother, Marlee (Tara Riggs), lives with her teenage son James (JimMyron Ross). Marlee works in a lousy job cleaning latrines. James is on break from school and pays visits to young drug dealers he owes money to. Rudderless and confused about his dead father, a recent suicide and Lawrence's twin, who never visited him, James turns to desperate and risky behavior that he tries to hide from his mother. The drug dealers pay a threatening visit to James's house.

Back from the hospital Lawrence remains so paralyzed by grief over his brother's suicide perishables are going bad in his little convenience store and he can barely speak, let alone reopen the store and resume normal life. Marlee gets fired from her job and there's no money. James wanders the fields, his only friend perhaps the family dog, the half-wolf Juno. Slowly, the three let out their grievances and begin reconciliation and a solution that involves the property the twins' late father left them and an uneasy cooperation between Lawrence and Marlee.

Hammer's filmmaking, which got him consideration at the Berlinale and two top prizes for directing and cinematography at Sundance in early 2008, involves a strong camera and meticulous natural sound (with no music), but above all the director's own commitment to humanistic integrity. His various models include Mike Leigh, Charles Burnett, and the Dardennes--Leigh for the attention to family conflicts, Burnett for truth about African-American life, the Dardennes for a method in which the camera literally dogs the footsteps of ordinary people in crisis.

This isn't digital but 35 mm. Technicolor in widescreen, by Lol Crawley, edited by Hammer. Dolby Digital sound designed by Kent Sparling of George Lucas' Skywalker Sound and edited by Julia Shirar (who's worked with Sofia Coppola and Noah Baumbach) was designed by Sam Watson, a Mississippi native, all with close, committed involvement in the project.

Essential to Hammer's approach was to use local people in the main roles and a screenplay whose dialogue was frequently rewritten by the actors who embellished their scenes with improvisation. Even when James' dialogue at some points is nearly inaudible, the sound crew kept that. Though this may be a dubious nod to authenticity, the film is so involving that it hardly leaves the viewer time to think. If this is the Dardennes, it is the Belgian brothers working in top form--save for the ending, which is no resolution or even a question mark, just an abrupt blackout. However, the whole second half of the film is a struggle toward resolution that gives a surprise sense of hope slowly emerging out of what middle-class viewers in particular might tend to see as an utterly hopeless situation.

Seen as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008. To be distributed by IFC Films in late August 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 12:59 AM.

-

Celine sciamma: Water lilies (2007

CELINE SCIAMMA: WATER LILIES (2007)

ADELE HAINEL, WARREN JACQUIN, PAULINE ACAUART

Portrait of young girls in flower

Water Lilies is a well-made first film from France about young female sexuality and friendship. Sciamma works with specialized, slightly sanitized material that is as off-putting to some as it is alluring to others. The film focuses exclusively on three middle-class teenage girls in a tidy new Paris suburb. Their lives revolve around a big indoor swimming pool where two of the three are part of a synchronized water ballet team.

Such distractions as parents, siblings, work and school have been neatly excised from the equation. The central sensibility belongs to the attractively sullen but skinny Marie (Pauline Acquart), who is not on the team, but thinks she would like to be. Marie worships Floriane (Adele Haenel), an alluring blonde and team standout whom the boys are after. This takes Marie away from her former best friend, also a member of the water ballet team, the somewhat plump Anne (Louise Blachere). Being less special Anne is more truly accessible to the boys. Floriane, like this film, promises a bit more then she truly offers. Marie has the more essential quality for a teenage girl: she suffers inwardly. Floriane doesn't so much suffer as jump into situations and then bolt.

Marie is dazzled by the glamor of the water ballet as well as Floriane. Floriane takes advantage of this to make Marie first her slave and a cover for her assignations, then, lacking any other friends, her confidante. All the other girls think Floriane a slut, an illusion she encourages in the men and boys she teases, because it leads them on. She suffers the pretty girl's fate of being not a person but an object, and she can't resist the validation the boys give her by wanting to kiss her and bed her, but she doesn't really care about any of them and knows her involvements with them are a trap. Enlisting Marie to act as her pal so her (unseen) mother won't know she's going out to meet boys, she also gets Marie to rescue her from the boys later. It looked the opposite at first, but Floriane needs Marie as much as Marie thinks she needs her. Anne is left with her discomfort with her body and a desire to get laid that's earthier and more real than the other girls'.

Keeping all external context at bay, Sciamma can highlight subtle shifts in the delicate equation of the three girls' goals and interactions. On the other hand the film's water madness, which includes lots of showering and spitting as well as underwater swimming shots, makes it feel completely airless at times and some of its 95 minutes do not pass so quickly. Luckily the film has a sense of humor and lets the trio sometimes forget their ever-present goals and avoidances and just do silly, pointless girl things. It's the offbeat moments that give the film life; too bad in a way that there aren't more of them. But Sciamma has the courage of her obsessions and what remains as one walks out of the theater is the personalities and their dynamics. Along the way of course it is pleasant also to watch the swimming and to gaze at the girls, who understandably love to gaze at themselves.

<SPOILER ALERT>

There's no great revelation or drama on the way, but things get a bit more interesting when it emerges that Marie doesn't just admire but truly desires Floriane and is jealous of her boyfriends--whom Floriane always stops before they go all the way. In a typical irony of this kind of plot, Floriane actually decides she wants to have her first real sex with Marie--but Marie is the one who holds off, because she knows it won't have the significance to Floriane that it will have to her. When it happens, it's a timid, mechanical affair. Meanwhile Anne has a huge crush on Francois (Warren Jacquin), a male swimmer, but of course he is after Floriane. Boys are not an element that's been subtracted and there always seem to be several dozen ready at poolside or on the dance floor, but they are just bodies and faces, available studs.

Water Lilies, whose actual French title Naissance des pieuvres ("Birth of Octopi") has been given various interpretations, none of which I quite follow, debuted in April of last year to fairly good reviews in France, it appears. It has gathered a couple of awards in France and three Cesar nominations; and was presented in the Un Certain Regard series at Cannes. It has a US distributor, Koch Lorber, and opened in New York April 4, 2008.

Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 01:06 AM.

-

Barry jenkins: Medicine for melancholy (2008)

BARRY JENKINS: MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY (2008)

WYATT CENAC, TRACEY HEGGINS

Medicine and melancholy

Micah (Wyatt Cenac) takes Joanne (Tracey Heggins) to the Museum of the African Diaspora on a Sunday afternoon. They woke up that morning in somebody else's house not knowing each other's names after a one-night stand at a party where they both got very drunk. It's San Francisco. They're black. They ride bikes. She was very unfriendly at first, not just because it was a drunken coupling but because she has a white curator boyfriend she lives with who just happens to be in London for the moment, but she loves him.

The first part of this first film by Barry Jenkins, which is shot in digital video tuned to be almost but not quite totally drained of color (like the city, as we are to learn), with pale grays and very white whites, is sustained by Micah's efforts to make Joanne want to spend some time with him. He thinks they ought to get to know each other, and it's a Sunday. She's not at all interested at first. They're both hung over, after all. She lets him take her home in a taxi and then just gets out and runs. But she leaves her wallet on the floor. To go back and find her it takes a search, on his bike, across town, because the address on her license isn't current. The film is also sustained by being very specifically shot in San Francisco. When Joanne goes to a gallery to run an errand it's a very specific gallery. The Museum of the African Diaspora is the Museum of the African Diaspora. The light is San Francisco light. Micah and Joanne are young urban sophisticates. That, as Micah points out, is not only specific but makes them a small minority of a small minority, because gentrification has shrunk the city's blacks to 7% of the city population (New York's proportion is 28%).

Later buying groceries for dinner at his place (because Micah succeeds and Joanne does spend the day with him, and more) they happen upon a group discussing what appears to be the imminent banishment of rent control in San Francisco. Is Jenkins lecturing us, or just treading water? It doesn't matter so much, because the interactions of Micah and Joanne and the wry, cautious words they use when they talk to each other remain central, and are as specific and accurate to who they are (if not to San Francisco) as the cityscapes and the special light.

These two fine actors and this sensitive filmmaker certainly know how to make it real and to record how unpredictably things change from minute to minute. When Micah takes Joanne to the museum, instead of SFMoMA (her original suggestion), and then to the Martin Luther King Memorial at Yerba Buena Center, maybe it's turning into a pretty cool date. But when he leads her over a little bridge there and says, "This is like LA," she just rather coldly says, "Never been," and then, rubbing it in once more and pulling back, "This is a one-night stand." A ride on the merry-go-round at Yerba Buena, she seems to be saying, isn't going to change anything. This delicate homage to a moment is also a rueful acknowledgment of how hard it is to alter the way things are.

And it has to be a bit of a lecture, because Micah is "born and raised," while Joanne is a "transplant," and he wants to remind her how the Fillmore and the Lower Haight were wiped out in the Sixties in "Urban Redevelopment:" goodbye black people, goodbye white artists. Micah lives in an immaculate little apartment in the Tenderloin. Micah, as the voice of Barry Jenkins, wants to reclaim San Francisco for everyday people.

Actually, Micah and Joanne seem like a perfect couple. Is that why they can't be together, except for this one day? You want to just shout out to them, "Can't you just be friends?" They fit so well together. Is this Medicine for Melancholy or jut melancholy? Maybe it's medicine and melancholy. That must be it. A fine little lyric of people and a place. And wholly without cliche' except maybe for the tag-line: "A night they barely remember becomes a day they'll never forget. "

Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008. This had its debut at SXSW, the South by Southwest Interactive event in Austin, Texas. In San Francisco Medicine for Melancholy shared the Audience Award for Best Narrative Feature with Rodrigo Pla's La Zona.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 01:07 AM.

-

Gillies ya-che yang: Orz boyz! (2008)

GILLIES YA-CHE YANG: ORZ BOYZ! (2008)

LEE KUAN-YE ON THE SHOULDERS OF PANG CHIN-YU

Kids fleeing from reality in Taiwan

A lot of twee meanderings have to go by before some human emotional content enters this cute but disorganized story about two mischievous schoolboy pals whose gym teacher nicknames Liar No. 1 (Pang Chin-yu) and Liar No. 2 (Lee Kuan-yi). Yang lets every shot and every scene run too long; the nearly two-hour film could benefit from some radical cuts.

Nonetheless first-timer Yang, previously author of Blue Gate Crossing, a successful Taiwan youth novel about teenage girls that was made into a movie by Yee Chi-yen, does have a grasp of the boys' imagination and gets nice performances from his young stars. The film, which includes animated sequences by Wang Teng-yu involving the boys' fantasy escape, the Kingdom of Orz and "Qatar King," is technically accomplished and makes good use of local settings in its Taiwan coastal town of Danshui and dozens of cooperative extras.

Though many scenes take place at school, classroom activities and individual classmates aren't the focus because they aren't for the boys, who also rarely confront the adult world. For their constant pranks (a scam to grab classmates' money opens the film), No. 1 and No. 2 are forced to spend much of their summer repairing library books after school. But they use their time scheming to fly to Orz, imagining a bronze school statue coming to life, and on other boyhood follies.

Liar No. 1 is the bigger boy and takes the lead, and has a peculiar, deranged father. This father and son are vaguely reminiscent of Kurosawa's Do-des-ka-den, and there's material here for a heartbreaking study of deprivation and loneliness. The film winds up spending more time with the living situation of Liar No. 2, who's reluctantly cared for by his mildly abusive shopkeeper grandma (Mei Fang), who doesn't like her son's farming out his kids, and actually loses his baby daughter, Mei--who No. 1 steals as a joke, but then loses in a park.

Granny goes bonkers, but the sequence wanders off at the end, and what preoccupies the boys and the film much more is their project to save money so they can go to the Kingdom of Orz--and their desire to get hold of a winning coupon to get the special edition Qatar King from the local toy shop.

"Orz" also refers to an emoticon of Japanese origin depicting a figure bowing toward the left and denoting surrender, dejection, or deference. Perhaps it refers to the obedience to adults No. 1 and No. 2 don't want to grant. In that sense they're certainly not "Orz boyz," and adults don't come off as very supportive or helpful here.

The filmmaker in Chinese style is also known as Yang Ya-che. Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 01:09 AM.

-

Philippe barcinski: Not by chance (2007)

PHILIPPE BARCINSKI: NOT BY CHANCE (2007)

RODRIGO SANTORO

Urban intersections in São Paolo

Not by Chance (Não Por acaso) is set in São Paolo, Brazil. Its crossed-paths (Amores Perros, 21 Grams, Babel, Crash) plot structure is getting pretty tired by now, but this is a sophisticated and polished and engaging enough work to have been bought an overseas branch of Twentieth Century Fox. It's already on DVD.

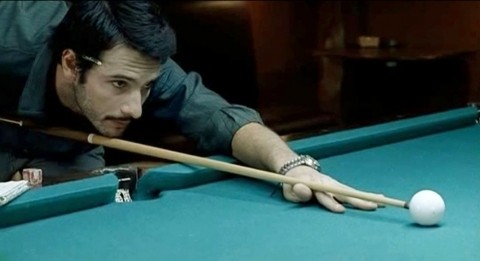

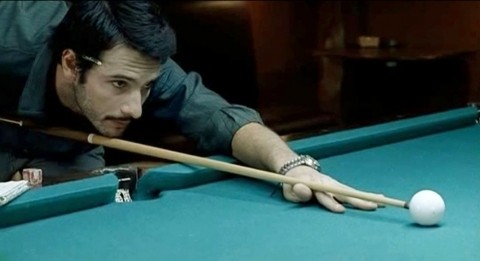

We begin with Enio (Leonardo Medeiros), a weary traffic controller who works in a large visually impressive control room. Shortly after a reunion with his ex-wife Monica (Graziela Moretto), who tells him his daughter Bia (Rita Batata), now grown, wants to meet him, he spies an accident and, rushing to it on foot, miraculously in a few minutes, sees Monica and her current husband lying dead. Meanwhile inter-cut with Enio's story is one of a university student, Teresa (Branca Messina), who rents out her large apartment to move in with her boyfriend Pedro (Rodrigo Santoro), an expert pool player who, like his deceased father, builds pool tables. Teresa's mother incidentally, like Enio and Pedro, is a kind of control freak. Teresa's old flat's new occupant is Lucia (Leticia Sabatella), a commodities trader particularly interested in coffee. In the course of the film relationships will be rearranged.

There's a parallelism between Pedro's diagrams of pool play (which he talks through mentally in voice-overs) and Enio's ideas about fluid dynamics, which his boss wants to utilize in some sort of unspecified more "humane" traffic system (rather than a German system of "smart" traffic signals he's not keen on adopting). Traffic controlling as seen here is fabulously technical and precise, while pool and cabinetry of course are art forms. The symbolism avoids seeming too forced because each area of expertise is presented interestingly.

The trouble with these schemes of interconnection, stressing the dire--people do interconnect under positive circumstances, after all--and the arbitrary is that they will seem, well, arbitrary, cooked up by the screenwriters (and there were three, Barcinski, Fabiana Werneck Barcinski and Eugenio Puppo) to give a story a sense of life's complexities that only a long novel, or better yet a series of novels like Proust's In Search of Lost Time or Anthony Powell's Dance to the Music of Time, can really convey. Representing several clusters of characters in a film of just an hour or two runs the risk of feeling like a chopped-down TV miniseries.

Nonetheless this first feature shows Barcinski to be a fluent and accomplished filmmaker. He gives us a sense of urban anxieties with the focus on apartment-hunting and traffic snarls. It's cool the way he uses phantom images of the pool balls to show the player's control to contrast with the movements of a girl killed through a random error in traffic. Since this sort of story views life diagrammatically, Barcinski seems to feel, why not diagram it openly? And it works. What you can't diagram are joy and grief, and that's where the actors come in handy...

Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008. It was shown at the Chicago and L.A. Latino film festivals and won a prize at the Chicago one.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 01:10 AM.

-

Mushon salmona: Vasermil (2007)

MUSHON SALMONA: VASERMIL (2007)

NADIR ELDAD, DAVID TEPLITZKY, ADIEL SAMRO

Beersheba ain't for sissies

This rather downbeat Israeli first film about soccer and social and ethnic problems focuses on three at-risk teenagers whose involvement in a team gives them some hope of saving their otherwise messy lives. At center stage is the luminously sullen Russian immigrant Dima (David Teplitzky), who's involved in petty drug dealing with shady, older fellow countrymen and despises school and his unemployed stepfather. His mother wants him to play the piano at some school ceremony, but he doesn't even go to school most of the time.

The 100% Israeli is Schlomo, (Nadir Eldad) who also has brutish, gangsterish connections and a violent attitude; he's hostile toward his equally mean, violent (and much bigger) boss at a pizza shop. Schlomo however shines at soccer and is captain of the little team coached by yet another tough cookie, Matan (Matan Avinoam Blumenkrantz).

Adiel (Adiel Samro) was born in Israel but as an Ethiopian he's still very much an outsider. He wears a yarmulke, ostensibly because he used to go to a religious boarding school, but perhaps also because people still question whether Ethiopians are really Jews. He's a good soccer player but has to overcome racial prejudice to get to show his ability, and must also worry about a sick mother and a little brother.

At the Jerusalem Film Festival last July Vasermil was viewed as breathing life into the proceedings and it won the Wolgin prize over The Band Visit. Judges admired the nervously expressive camera and use of non-actors and naturalistic sequences worthy of Ken Loach. It's significant that Salmona spend ten years in London. He grew up in Beershiva, where the film is set; Vasermil is a stadium there. He was aware that things were always tough in that town and have gotten tougher.

The Jerusalem judges also were impressed by the director's gritty confrontation of social problems and his avoidance of any Hollywood resolutions. There's no triumph in the Big Game coming. On the other hand, the sequences of soccer play are unusually natural. The only stretcher is the idea that Dima is only water boy and then, because he's a scrappy kid, is called in by Matan to replace the injured goalie--and immediately commands the position.

The implication is that a survivor of the hardscrabble life of the streets can excel in other spheres. Unfortunately the dangers and unwanted commitments faced by Schlomo and Dima are too great for them to ride sports to worldly success. And though Adiel is good and likes playing, he's unwilling to leave his family again to accept a scholarship.

It's indeed impressive the way Ram Shweky's camera in Vasermil makes these boys and the people they must deal with loom very large on the screen, and there's certainly no fluff in Reut Hahn's editing. Not every moment or every performance is convincing, however, and the roughness sometimes seems like disorganization. It would have been nice if Salmona had let his scenes and his characters breathe a bit more. Dividing up events among three boys may be essential to conveying a segmented and restless modern urban society, but while depicting social and family and ethnic conflicts, Salmona doesn't allow his main characters to emerge fully as personalities, and only Adiel gets to have anything like a gentle side. It's fine to avoid a Hollywood ending, but there's nothing very artistic about the way the narrative just suddenly stops. I'm not utterly convinced this was better than all the competition for the New Directors Award at the San Francisco festival (which it won), but it does convey vividly a sense of diving into social realities.

Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-11-2010 at 12:08 AM.

-

Alex rivera: Sleep dealer (2008)

ALEX RIVERA: SLEEP DEALER (2008)

LUIS FERNANDO PEÑA

Tripping at the border

Sleep Dealer is a bright, shiny, hard-working little sci-fi movie that bristles with allegorical and literal messages about technological imperialism, globalization, the exploitation of foreign labor and other serious matters. It's also about the theme of Sterne's A Sentimental Journey: a "traveler" who essentially stays at home--and about how the world's clamoring have-not South in the future will be as full of technology as he North, as indeed it is already. The means of exploitation will be extended into the land of the exploited.

What saves this heavy talk is a soulful innocent who's connected, or 'branché,' as the French say--in the most literal sense: he gets fitted with electronic "nodes" all along his arms, neck, and back, so he can be plugged to a central computer in at the border and thereby help America to achieve its fondest dream: making others do all the menial physical work, but without allowing them to enter the country. Thus Mexicans in virtual factories , at a distance, in 12-hour night shifts, walled off by a militarized barrier, do America's hard labor by proxy just outside the actual physical USA. Memo (Luis Fernando Peña), Sleep Dealer's young hero, comes to the "Sleep Dealers" in a mixture of desperation and hope, to save what's left of his little family in a rural village in Oaxaca.

Memo isn't a lily-white Candide. He has hope and love to give, but he also has a kind of primal curse upon him: he has caused disaster to his nearest and dearest by eavesdropping on a totalitarian northern force that sends drones to make strikes anywhere and blow up what it defines as "bad guys." They detected his radio, assumed he was an enemy, and brought down tragedy on his family. Both as penance and because nothing keeps him in the village any more, he goes to Tijuana, "the world's largest border town," and gets a pretty woman named Luz (Leonor Varela) whom he meets on the bus to fit him with the necessary set of body nodes. She calls herself a writer. Actually she works for a high tech firm that sells memories, and in this Orwellian world of spiritual deprivation, his experiences become fodder for her.

All the machinery in Sleep Dealer is grotesque and comic but it works inexorably to serve the North. Farming has become impossible for Memo's father since the river was damed and a private company took control of the local water supply. In their part of Oaxaca the "future" has become a thing of the past, the father says. They must appease a machine that will shoot them if they disobey, just for permission to go to a river and collect water that they must pay for. Later another threatening gadget gobbles up Memo's Sleep Dealer earnings and transfers them, minus a big fee and taxes, to his family further south. He can talk to his mother and brother on a videophone.

It seems an unintentional irony in Rivera and David Riker's screenplay that the man who ultimately helps Memo and his family, though of Hispanic origin, is an American "pilot,' himself "connected by nodes: the system not only stands for immigrants who can't work at home but for how technology alienates people from real work everywhere.

Sleep Dealer was made after a long struggle through Sundance financing, and got good buzz at the Sundance Festival itself. Because the Hispanic-oriented distributor Maya is buying the film and may finance a substantial stateside theatrical release, Rivera was saying in December, it may have a better fate than the mere straight-to-DVD issue Justin Chang of Variety predicted. It's hard to see why Chang, who did acknowledge the film's colorful visuals and "A for effort" f/x, indeed remarkably polished and stylish and at times even mind-blowing considering the low budget, describes Pena, who's like a combination of Javier Bardem and Robert Downey, Jr., as "a blank." The actor makes a sympathetic little man hero in the classic picaresque mold, and the film's story dramatizes its theme of how immigrants are at once exploited and excluded in a way that's not only full of vividness and irony, but trippy. Though Rivera said his real models are more in sci-fi literature than film, one can see why he'd also describe Terry Gilliam's Brazil as "the Holy Grail."

Rivera made the film in Spanish in Mexico, but is an American whose first language is English. One parent is from the US and the other from Lima, Peru, and he grew up in New Jersey. He has previously explored global have/have-not issues in documentary formats.

Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival. It was also in the New Directors/New Films series at Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-11-2010 at 12:09 AM.

-

ABDELLATIF KECHICHE: THE SECRET OF THE GRAIN (2007)

ABDELLATIF KECHICHE: THE SECRET OF THE GRAIN (2007)

HAFSIA HARZI, HABIB BOUFARES

Tragicomic epic of Arab immigrant life in a French port town, a new triumph for Kechiche

Abdellatif Kechiche, who is also an actor, stands with Turkish-German director Fatih Akim as the preeminent director dealing with diaspora experience in western Europe. He was born in Tunisia but was brought to France at the age of six and grew up in Nice. La graine et le mulet, the title, refers to (mullet) fish couscous (grain) and Kechiche has said he's as stubborn as the mullet. The action is in the southern French port town of Sète. Most of the cast are non-actors.

Though marred by a jittery camera in intimate scenes, over-close closeups, and some sequences that are allowed to run too long, The Secret of the Grain is nonetheless a triumph, an emotionally powerful, overwhelmingly rich, epic-feeling tragi-comedy that overflows with wonderful performances, evokes a host of masters including Jean Renoir and the Italian neorealists, and fairly bursts off the screen with its loving and complex portraits of Magreban society in France and the harsh world in which they struggle and survive. The main focus for all this is food: two grand meals, one intimate and familial, the other in a projected couscous restaurant on an old boat where friends and family and local officials are all invited to show off cuisine and entertainment in an effort to prove that an old man at the end of his tether can, with the help of his family and friends, make a go of it in a new business, against all odds. Kechiche and his cast focus not so much on any plot-line arc, though there are dramatic turns of events right up to the end, but on the way they work as an ensemble to make each moment come alive. In the somewhat stilted, over-polished and over-sophisticated and often dry world of French cinema, it's not hard to see how the rough, irresistible energy of the world Kechiche brings to the screen here would seem a welcome tonic. And, it has to be admitted, giving the same very gifted Arab director the run of the Césars twice can't help but be soothing to the consciences of the left-liberal intellectuals who tend to dominate the world of French film criticism. It doesn't hurt that Secret is offered by Pathé and has the imprimatur of the prestigious producer Claude Berri.

Kechiche's previous (and second) film L'Esquive ("The Avoidance"), retitled in English Games of Love and Chance (after the 18th-century playwright Marivaux's work that's central to the plot) which, like Secret won four Césars, including Best Director and Best Film, was about the young mixed population of children of immigrants who live in the ghetto-like suburban Paris banlieue. This new story is a homage to the "fathers," the generation of Kechicne's parents, who immigrated to France forty or fifty years ago.

Hence the protagonist is the sad but determined Slimane Beiji (Habib Boufares), who as the movie begins is told by his boss at the port shipyard workshop that, now sixty-one, he is no longer "rentable" (profitable), his work is too slow, he doesn't keep up with the schedule on projects. Threatened with no benefits because earlier in his 35 years at the site he was off the books and now offered only half-time status, he quits. He lives in a room in a little hotel run by his lover, Latifa (Hatika Karaoui), whose daughter Rhn (Hafsia Herzi) considers Slimane her own dad and defends him against his mean sons by his ex-wife Souad (Bouraouia Marzouk). He owes her alimony, but brings fish instead. The sons say he ought to go back to the bled, the old country; they want to be rid of him.

Slimane's son Hamid (Abdelhamid Aktouche) is married to a Russian woman. The family evidently knows about Hamid's philandering and especially his affair with the deputy mayor's wife--the need to conceal which becomes a plot pivot-point.

While Slimane is alone in his little hotel room Souad has a big fish couscous dinner with their offspring and their French husbands and children. This sequence is irritating at times for its clamorous, shifting closeups, and its cacophonous talk, but at the same time the way this lively, tumultuous gathering in close quarters has been shot is a tour-de-force of complex naturalism. When the sons bring Slimane a dish of the fish couscous, he gets the idea of enlisting his ex-wife to be the cook in a restaurant he might establish in an abandoned ship. Rhm goes with him to the bank and city offices to present the project where they're politely received, but not given the green light. This is where the idea comes to give a grand dinner on the ship to convince everyone Slimane and company can make a go of it. A lot of the second half of the movie consists of this dinner.

The naturalism of the sequence may be suggested by the fact that Bouraouia Marzouk actually did a lot of the cooking for 100 people for the dinner. The theft of Slimane's Mobylette is a conscious homage to De Sica's Bicycle Thief (Ladri di biciclette). La graine et le mulet is a thrilling, amusing, moving, excruciating screen experience that takes Abdellatif Kechiche to a new level of accomplishment, but the vagaries of his methods will continue to create enemies as well as admirers as he goes along. As Jacques Mandelbaum wrote in Le Monde, The Secret of the Grain "mixes romance and social chronicle, melodrama and comedy, the triviality of the everyday and the grandeur of tragedy. A simple family meal becomes a classic sequence, a table of old immigrants becomes a Greek chorus, a belly dance a high point of erotic vibration and dramatic tension." For all its flaws, this movie packs a huge wallop and brings Adbellatif Kechiche to the brink of greatness.

Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-31-2009 at 04:10 PM.

-

Bard breien: The art of negative thinking (2006)

BARD BREIEN: THE ART OF NEGATIVE THINKING (2006)

Stop smiling and it'll hurt less

Breien's film about handicapped people is a corrective. It mocks programs that offer false cheer, repress the need to express anger, and don't give people who need to do so the right to take things in their own hands.

Things get lively as soon as Tori (Kjersti Holmen),a smug therapist who works for the Norwegian state health system, takes her group of variously dysfunctional folks in a van to the house of Geirr (Fridtjov Såheim), a wheelchair bound man who's refused to join the program. If she thinks she's going to win Geirr over, she's got another think coming. As we see before the group arrives, Geirr, who's paraplegic and impotent from a car accident, doesn't get along with his wife Ingvild (Kirsti Eline Torhaug) and likes to spend his time getting high, drinking beer, listening to Johnny Cash albums and watching war movies.

Tori has brought quite a motley crew. There's Lillemor (Kari Simonsen), a middle aged divorced woman in a neck brace. Marta (Marian Saastad Ottesen) is a pretty woman. She is paraplegic too, from a mountaineering accident. Gard (Henrik Mestad) is her self-righteous, self-pitying boyfriend. Asbjorn (Per Schaaning) is an older man who is seriously damaged by a stroke and can hardly speak. Tori imposes a regime of forced cheer. It's obviously gone too far with Marta, who wears a fixed rictus smile. Lillemor is perpetually whining. She gets to voice her complaints into the knitted "shit bag," which Tori passes to people who want to say something uncheerful.

Ingvild has invited the group over because she can't take Geirr's withdrawn grumpiness much longer and is desperately hoping they can get through to him. The surprise is that it's he who gets through to them. Geirr doesn't want anybody to try to tell him that things are okay for him. By shaking up the group and expelling Tori and encouraging the others to admit what's really going on inside or alternately dropping their facades of self-pity, Geirr releases a swoosh of energy in the group that flows back to him. It turns out he's a pretty together fellow. He becomes the leader--and the exponent of The Art of Negative Thinking. The group helps him by pointing out that of all of them, he's materially the best off. He lives in a big, beautiful house, while some of them are struggling to survive financially. Others also reveal what else is going on with them, that Tori's bossiness had kept from coming out. Marta stops smiling long enough to point out to Gard that his failing to tie her off is why she fell. On the other hand he needs to stop agonizing over that and move forward. Lillimor deesn't really need the neck brace. Asbjorn gets so involved in the proceedings, which involve some useful drunken revels, that he regains some of his power of speech. In time Tori is allowed back to apologize and the air has been cleared.

The solutions the group, with Geirr, arrive at relate to 12-step recovery, which assumes as a given that people must help themselves and you don't know what it's like unless you've been there yourself. Nobody who hasn't dealt with the minute to minute hardships of being disabled has the right to tell handicapped people to keep their chin up. You have to acknowledge the dark side to get to the light. When being honest is the prime requisite it also comes clear who has been faking and who can get a lot better fast if they try.

But this isn't some kind of instructional film. It's a somewhat theatrical happening, whose improvisational surprises at times suggest the work of Lars von Trier. The actors manage to seem real and at the same time somewhat stylized.

This is a nice little film that somehow seems ideally a product of the angst-ridden world of the Scandinavian northland. But a lot of what goes on here is universal, and by no means restricted to the handicapped--or to Norwegians.

Seen as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-26-2014 at 02:31 AM.

-

SERGEI BODROV: MONGOL (2007)

SERGEI BODROV: MONGOL (2007)

ODNYAM ODSUREN (as the young Temudjin)

To the right of who?

Mongol, the Russian-directed semi-historical epic (big emphasis on the semi- here) shot for $20 million in China (and Mongolia and Kazhakistan) with a multi-national cast and crew and Japanese and Chinese stars, purports to depict the first thirty-five years of the life of the emperor Genghis Khan. I say "purports," because not much is known of this period and even in depicting legend, Bodrov chooses to leave out many of the essential connectives that make a good story (or fairy tale or legend). Temudjin, as the young super-Khan is called, is a yoked prisoner, for example, awaiting execution; then, inexplicably, the yoke is off and he's free. He sinks through thin ice deep into the frozen water below; then, inexplicably, he's lying on land and getting rescued. He is languishing in a Chinese prison--his face seeming to acquire a patina of dust and sand (I liked that part: Bodrov excels at faces and tableaux); then he's miraculously found by his faithful wife Borte. She throws him a key and sets him free. Then, inexplicably, he is leading a vast army to defeat his arch rival. Over and over, how we get from point A to point B is left on the cutting-room floor. This is enjoyable as spectacle but unsatisfying from other standpoints.

How Genghis Khan got to be Genghis Khan, in short, is one thing this movie doesn't begin to try to explain. Could anyone? That I don't know; but Mongol presents a its biographical narrative without the connectives that make sense of a life. Despite lots of dramatic scenes with snappy dialogue, striking images, and above all computer-assisted battles with crunching bones and crackling arrows and ringing swords, the film has an epic style without epic themes because its great issues are not so much resolved as abruptly, magically removed. This may in fact be more an epic love story than anything else. It is that in the backhanded way the Odyssey is a love story, because, though Temudjin is away from Borte a lot of the time as Odysseus is mostly away from Ithaka and Penelope, Mongol's opening sequence gives Borte a primary importance, because she (as played by Bayertsetseg Erdenebat), belonging to another tribe, a liberated young woman of the twelfth century, isn't chosen by but chooses Temudjin when he's nine years old and she's ten. It's not supposed to be that way--and maybe it wasn't; it seems a bit implausible. Temudjin is traveling with his Khan (tribal chieftain) father (Ba Sen) on their way to placate another tribe by choosing the boy's wife from their girls. When they don't, the father is promptly poisoned by the other tribe. And its leader, Targutai (Amadu Mamadakov), vows to kill Temudjin--but not for a year or so, because "Mongols don't kill children."

Well, what Mongols do or don't do seems up for grabs, and probably at the time, historically, "Mongol" itself must have been a rather vague concept. In fact that is another running theme: what's a Mongol? What are their primary values? There is no satisfactory answer, though killing and stealing are advanced as major concepts.

Surprisingly, since not too many are "to the right of Genghis Khan," and since he succeeds in wiping out all his enemies, Temudjin as played (as an adult) by the imposing Tadanobu Asano is a gentle-faced, zen-like fellow who's a strong advocate of fair play. Tadanobu, along with the somewhat over-histrionic Chinese actor Honglai Sun as Jamukha, his childhood blood brother and eventual arch rival, are both impressive. But the real star, with some substantial help from computer-generated effects, is the vast landscape of steppe, snow, mountain, and sky that dominates many scenes. With effective use of lenses and light, the filmmakers have created an epic look, and it's this, plus the authoritative acting, that make this film worth viewing--but only if you like this kind of thing and if you don't mind that you're not going to emerge from it with any historical knowledge. Said to be the first of a trilogy. One will approach the sequels with a certain reserve.

Shown as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival April-May 2008 and in US theatrical release June 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 06-29-2008 at 08:00 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks