-

OBVIOUS CHILD (Gillian Robespierre 2013)--ND/NF

GILLIAN ROBESPIERRE: OBVIOUS CHILD (2013)--ND/NF

JAKE LACY AND JENNY SLATE IN OBVOUS CHILD

Foul-mouthed girl comic gets sweet hunk

The vulgarity, sexual explicitness and compulsive personal honesty of female standup comic Donna Stern (Jenny Slate) protagonist of Obvious Child, which may suggest neurotic, self-destructive behavior, are in contrast to the movie's straightforward upbeat outcome. The movie, set in Brooklyn and Manhattan, begins with vagina and penis jokes, but turns out to be a rom-com whose denoument is a feel-good abortion sequence. Though Obvious Child has twists along the way, the oddest note may be the suggestion that a girl can still meet a Mr. Right, and on the rebound too. But what recommends the movie isn't so much its storyline as its appealing central character, sold by the from-the-heart style of its good looking, smooth talking star, Jenny Slate, a Saturday Night Live vet whose standup here becomes (within the film's storyline) strictly autobiographical.

Her first lines about her vagina onstage lead to describing her boy friend as "having a working penis." Perhaps working overtime, since as soon as the act's over this individual announces to Donna that he's leaving her for her best friend. When she gets drunk aided by her gay comic friend Joey (Gabe Liedman), she's joined by a tall, hunky, super-straight and "Christian" (Donna being very self-consciously Jewish) young businessman called Max (Jake Lacy).

When she goes home with Max, who is never turned off by any of her frank talk, they dance, act wild, and have sex. Next thing she knows, helped through the drama of a first pregnancy test by her friend (Suzanne Lenz), Donna indeed discovers she and Max didn't actually properly use a condom, and she's pregnant. As an extra, her place of work, a bookstore, is suddenly about to close. Dumped, pregnant, out of work.

Today's Apatow-style comedies are usually about young men avoiding responsibility. Here, where the woman is at the center, this is a non-issue. Max simply keeps coming around. He turns out to be a favorite student of Donna's business-school-prof mother (Polly Draper - from thirtysomething!), so Donna sees him not only at the bookstore but by chance at her mother's. Donna wants to tell him she's pregnant, but can't quite. She reveals it finally when Max turns up for one of her comedy routines, where she announces she is having an abortion, on Valentine's Day (there's a reason). Max neither advocates nor apposes this; it's not his decision. At first he bolts but he is soon back, and is simply present for the event to support it. Likewise Donna's mother is a breeze about the whole thing. She is just relieved the news is an abortion and not a move to Los Angeles; turns out she had an abortion once herself.

One obvious interval is an abortive evening at a fancy loaned apartment with Donna's comedy club boss Sam (David Cross), who is going to Los Angeles. What was just to be a drink is obviously an attempt to take her to bed, and she bolts. Sam is yucky, a clearcut Mr. Wrong. He makes the already appetizing Max look even more perfect. But Donna doesn't leap into the arms of Max either. Again belying the rules of rom-com that require making all the wrong moves, Donna simply does the sensible thing under the circumstances and accepts Max.

For conservatives about religion or childbirth the film's embracing of a possible mixed (Jewish-Christian) union and wholehearted acceptance of abortion might be doubly offensive. Certainly Max is a woman's fantasy of a knight in shining armor (who obligingly keeps his opinions to himself, except to approve). But Obvious Child's standup comedy dirty talk is combined with grownup attitudes and good sense and free of the usual sickly rom-com mix of of snide jokiness and sentimentality. There's not much to Obvious Child. It lacks the stars or the punch to be a big hit at the box office. But on the whole it's a pleasant surprise. It's a Sundance hit (which A24 paid a good price for there) that succeeds by not setting its sights too high, yet going its own way.

Obvious Child , 83 min., debuted at Sundance. It was screened for this review as part of the FSLC-MoMA New Directors/New Films series, where it is the centerpiece film, showing Thursday, March 27, 9:00pm at MoMA's PS1 and Saturday, March 29, 3:00pm at Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-01-2015 at 06:22 PM.

-

TRAP STREET (Vivian Qu 2013)--ND/NF

VIVIAN QU: TRAP STREET/SHUIYIN JIE (2013)--ND/NF

LU YULAI AND HE WENCHAIO IN TRAP STREET

Romance in the world of total documentation

One of the beauties of Trap Street, a quietly auspicious debut by Chinese former producer Vivian Qu, is its genre-jumpiing. It begins as a rom-com with coming-of-age overtones, then moves into noir-thriller territory, and winds up with strong hints of ominous sociopolitical sci-fi. And it's all flowing and natural thanks to seamless storytelling and editing, handsome cinematography, and cast members who act their heads off, without the effort showing. There's plenty to think about afterwards in this fresh, subtle film that has Hitchcockian overtones with its trapped innocent man theme. The young but experienced star Lu Yulai is excellent here, and we can only hope to see more very soon from this new director, Vivian Qu.

The very young Li Quiming (Lu Yulai) is working at several main jobs. He moonlights installing security cameras for a somewhat unsavory pal, and also at testing for bugs in hotel rooms. But his main gig is as a trainee for a private surveying company that tracks the ever-changing city. Quiming, whose mother (Xiang Qun) works in a mall stall and father (Zhao Xiaofei) is a woman's magazine editor, seems barely out of his teens. Video games are his favorite pastime, but he's also looking for girls and makes excuses to linger in a neighborhood he and his partner Zhang Sheng (Hou Yong) have been surveying when he glimpses the pretty, stylish Guan Lifen (He Wenchao). They stay for dinner to avoid rush hour and get caught in a downpour -- and Quiming spots her stranded under an umbrella and they give her a ride.

From then on Quiming is smitten by the mysterious LIfen. She is a bit out of his league, and also turns out to work at a secret lab on "Forest Lane," a street not on any map or GPS system. Lifen leaves a card case containing computer index data in the survey company car, which leads Quiming to her, though when he dresses all up to meet her her supervisor (Liu Tiejian), or so he calls himself, turns up instead -- a hint of trouble to come.

The film focuses wholly on Quiming, the buddies he shares a flat with, the parents he sees now and then, his various jobs, and captures his innocent youthful spirit. Typically when he and his survey partner rush into the car out of the downpour, the first thing he does is arrange his hair. And each of his few but key "dates" with Lifen is memorable, yet light-hearted (despite the dark undertones coming). She may be fancy, but he takes her to the zoo to look at monkeys; riding bumper cars; to a pool hall and dancing; they share soft drinks. His gesture of grasping her hand and reading off his latitude/longitude watch reading and saying"Quiming first held the hand of Lifen here" is a gesture out of the romantic novels cannibalized so skillfully at one time by Wong Kar-wai. Life seems to partake of Quiming's lighthearted spirit, or feed off it. But his innocence is his alone.

That innocence is shattered when on a date after a mysterious break (when Lifen's cell phone has been out of the system), we stay with Lifen, and Quiming seems to have disappeared. Hereafter Qu takes us down a dark and Orwellian road, one that may fit the age of Edward Snowden and whatever China's NSA is. Mystery and paranoia and worse seem ahead, but Qu wisely doesn't really explain anything, leaving Lifen's work and her role or the lack of it in what happens as mysterious as she was to start out with. She could be the future; she could be an angel of doom. She could be as innocent as Quiming.

A "trap street" in cartography terms is nonexistent street mapmakers hide on a map to protect copyright. But here it has an additional meaning, since the off-the-map street where the alluring Lifen works proves a dangerous lure for the young protagonist.

Highly recommended.

Trap Street/水印街 [Shuiyin jie], 94 mins., debuted at Venice 1 Sept. 2013 and was at Toronto and at least 18 international festivals, and was screened for this review as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center-Museum of Modern Art series New Directors/New Films, showing Fri. 28 Mar. 2014 6:30pm at Lincoln Center and Sat. 29 Mar. 4:00pm at MoMA.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-01-2015 at 06:21 PM.

-

THE STRANGE COLOR OF YOUR BODY'S TEARS (Hélèe Cattet, Bruno Forzani 2013)--ND/NF

HÉLÈNE CATTET, BRUNO FORZANI: THE STRANGE COLOR OF YOUR BODY'S TEARS/L'ÉTRANGE COULEUR DES LARMES DE TON CORPS (2013)--ND/NF

More gorgeous glossy S&M from the Belgian couple

The Belgian couple Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani's 2009 Amer (ND/NF 2010) was a celebration of or stylized homage to Italian Dario Argento-style slasher-horror "giallo," and their new one, the 2013 The Strange Color of Your Body's Tears/L'étrange couleur des larmes de ton corps is more of the same, presented as a more coherent whole but also, if read carefully, maybe more offensive. This time instead of being divided into three parts that don't fit together very well, it's one continuous feature, except that again the narrative element is limited, and the material is very repetitive and often spins into the purely visual or sonar. Again this is an evocation of genre for cultists that's more lush visuals and sound than a regular film. The sound and visuals are gorgeous, with the problem that if you don't like buckets of blood and people (particularly nude women) being cut to pieces with long knives, you may find the content of the images increasingly off-putting, as time wears on.

This time rather than focusing on the weird Freudian childhood of a little girl, as Amer initially did, the film has more of a detective-story premise (and giallo, by the way, comes from a Mondadori series started in 1929 and generally refers to what is called "noir" or French "romans policiers," Seventies slasher movies being just an offshoot). Dan (Denmark’s Klaus Tange) comes back to his Brussels apartment expecting to see his wife Edwige (Ursula Bedena) ), but it turns out for some time she hasn't been answering his phone calls, and when he gets home, she is missing and the door is chained shut from the inside.

This is the time when, to add a real policier note, the police need to be called in, but that doesn't go very far, and Dan starts an investigation of his own. Dan and Edwige's place is in a small, unusually handsome apartment building, which we're later told consists of subdivisions of what was formerly a large single preivate residence. As Jay Weissberg says in his not at all admiring Variety review, what follows is as interesting for the "fabulous art-nouveau spaces" this building affords as for any narrative content, which is hard to follow at best anyway. We get an over-sexed old lady upstairs (Birgit Yew) whose husband disappeared through a hole in the ceiling. We get a raven-haired young woman in kinky red leather. We get a building manager with news of former occupants and of double walls and connections between all the apartments. And this time we get a lot more slashing and blood. And decapitations.

Visually, this largely being an experiment in imagery, as in Amer, we get pinwheels, lots of extreme closeups, particularly of eyes and mouths; split-screens, kaleidoscopic effects, keyholes, holes, wounds, Weissberg implies, standing in for predatory pudenda (which he finds offensive; women might too). Again it all combines to present murder and cruelty and S&M with the glossy glamor of a fashion shoot. Mike D'Angelo, who saw this at Toronto, explains in his personal Letterboxed review that he initially liked how each successive person Dan meets launches into "crazily stylized digressive interludes," but was disappointed that the filmmakers eventually settle into "their meaningless narrative." He is certainly right, judging by these two films, that Cattet and Forzani "can't do a sustained story" (in feature-film terms). Normal viewers watching this film uninterruptedly in a cinema find it becoming very, very long toward the end, its beauty of image and sound not enough to offset a parade of repetitiveness and gore whose pure exercise in style might disappoint Argento. It's too aesthetic to be truly scary. But Cattet and Forzani have a formidable technique to work with if they could abandon their cultism and move on to an actual narrative film.

The Strange Color of Your Body's Tears/L'étrange couleur des larmes de ton corps, 102 mins., debuted at Locarno 12 Aug. 2013 and showed at ten or twelve other international festivals including London and Toronto. It opened in French theaters 12 Mar. 2014 with a mediocre critical reception (Allociné press rating: 2.9). Screened for this review as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center-Museum of Modern Art joint series New Directors/New Films (as was Amer in 2010).A Strand Releasing release. At ND/NF it shows Fri. 28 Mar. 2014 9:00 pm at MoMA and Sun. 30 Mar. 1:15 pm at Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-01-2015 at 06:44 PM.

-

SHE'S LOST CONTROL (Anja Marquardt 2014)--ND/NF

ANJA MARQUARDT: SHE'S LOST CONTROL (2014)--ND/NF

BROOKE BLOOM IN SHE'S LOST CONTROL

Misguided therapy

Anja Marquardt's dour first feature about a woman majoring in social psychology working as a sex surrogate is a drab exercise in middling indie style that offers fewer rewards than it might. Ronah (Brooke Bloom) takes on a small number of clients with intimacy issues who are referred to her through a therapist (Dennis Boutsikaris). Watching Ronah and the therapist consulting together on one of her clients in the therapist's office makes one suspect they, and particularly Ronah, whose face seems slow to register authentic emotion, may have intimacy issues of their own.

We don't learn much more about Ronah other than her dreary current life. Her apartment has a leak. The plumbers leave holes in the bathroom wall that make taking showers difficult. She has lonely meals in this apartment, except for one time with a female neighbor she invites over -- who later turns out to be suing her. She gives herself daily hormone injections, in order, she reveals later, to freeze her eggs in case she might later want to have a child. For reasons unexplained -- just her harried existence, presumably -- she has no time to have a boyfriend of her own. A Skype conversation with her brother in the country (Ryan Homchick) reveals their aged mother has wandered off, a worry that till the end of the film is dropped.

One skyline seen from a window indicates this is taking place in New York City. But locations, or any establishing shots, are a mere blip, part of the apparently intended coldness and colorlessness of a film that seems to partake of the problems it depicts. Any warmth or atmosphere might presumably disturb the angst-ridden mood, which may owe something to Lodge Kerrigan of Kerane (acknowledged in the end credits), though this film lacks the intensity and sense of place of Kerrigan's work. If the affection Ronah offers is intentionally generic, why should she have to seem such a blank otherwise? It's not till the title comes true that anyone breaks out of blandness, and by then the film is nearly over.

The one bright spot is Ronah's teacher and mentor (Laila Robins), who has done this kind of work herself earlier. She is a warm and spontaneous person, showing the field is not wholly filled with by-the-numbers geeks like Ronah and the referring therapist.

The trajectory is obvious. Ronah gets a new client, Johnny (Marc Menchaca), a bearded anesthetist's assistant, a particularly hard case that she feels is a challenge. Johnny is resistant at first even to arm-touching and barely willing to make eye contact. But aren't they all like this? We get no others to establish a frame of reference. "I want to crack him," she tells the therapist -- not a very warm and fuzzy way of stating her aim. Johnnny expresses dislike of Ronah and at one point says he'd like to strangle her -- a hint of danger left unheeded. Doubtless like other clients Ronah has dealt with, Johnny seems to have had bad past experiences that make him self-protective, and they keep him from wanting to have sex with anyone he knows, He won't tell Ronah who he does have sex with. (It's a sign of the screenplay's lack of clarity that it's unclear if her asking him about that is routine, or a breach of it.)

It's clear Johnny will warm up, Ronah will get too interested in Johnny, and there will be trouble. At the clinically formal first meeting when Johnny must sign an agreement and take a mouth swab sample to show he has no sexually transmitted diseases, yet he is informed that the meetings are "not for sexual gratification or entertainment." What are they for, then? This is another confusing curve ball from the script.

In the event, when they both get interested, sexual gratification clearly occurs. But that's where the trouble starts. Maybe after it's clearly all gone wrong, Ronah ought to decide to get a masters in something else, or realize social psychology doesn't require playing at sex therapy. But the ending does't take Ronah anywhere, except upstate to visit her brother.

Marquardt may intend to provide an unnerving portrait of contemporary alienation. But what we see is a film without warmth based on a screenplay that lacks clarity. There is something clumsy about She's Lost Control (even the title is gauche) that its intentionally "austere" style can't mask. If you want to see a screen treatment about a sex surrogate, better to watch Ben Lewin's superior The Sessions, an interesting, touching, and true story admirably acted by Helen Hunt as the sex therapist and John Hawkes as the needy and grateful client. Helen Hunt's character shows that performing this job with professional restraint need not mean a lack of warmth and humanity. As for She's Lost Control, it's better avoided.

She’s Lost Control, 90 mins., debuted at Berlin Feb. 2014. It was screened for this review as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center-Museum of Modern Art series New Directors/New Films, where it shows Sat. 29 Mar. at 9 pm at Lincoln Center and Sun. 30 Mar at 4:30 at MoMA.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-01-2015 at 06:50 PM.

-

SALVO (Fabio Grassadonia, Antonio Piazza 2013)--ND/NF

FABIO GRASSADONIA, ANTONIO PIAZZA: SALVO (2014)--ND/NF

SARA SERRAIOCCO IN SALVO

A new pair of filmmakers to reckon with in Italy

My sympathies were with Fabio Grassadonia and Antonio Piazza's first feature Salvo all the way, even when it disappointed expectations early on with its strange jump from a gun battle and mafia killing to an almost too close and prolonged focus on a beautiful blind girl, a relative of the assassinated man, who somewhat implausibly regains her sight. It's a wholly original mix, and the assassin, who goes into hiding in Sicily, where all this transpires, with the blind girl, has some of the chiseled, laconic mystery of Alain Delon in Jean-Pierre Melville's classic Le Samouräi. But the filmmakers are trying to pull a fast one on us, bringing out all the trappings of an Italian gangland thriller and just letting them wither away. That stuff is durable. It can't wither away. However the Sicilian interiors, overdecorated and decrepit in a Victorian-Italian way, the industrial exteriors, rusty, clanging and abandoned to mafiosi, are memorable. So is the light. And so are Palestinian actor Saleh Bakri as the assassin (who may bring Chemises Lacoste back in style), and Sara Serraiocco as the blind girl he literally loves to death. Talk about doomed romances. This is a genre-bender, with elements of noir thriller and operatic romance and some of the images, dialogue and pace of spaghetti western.

And there is the memorably odd piccolo-borghesi couple (played by Giuditta Perriera and Luigi Lo Cascio) at the first hideout, an old apartment, who serve Salvo (whose name,rather ironically, means "safe," as in "sano e salvo," "safe and sound," as well as being short for the common Sicilian name, Salvatore). And also Mario Pupella as the gnarly mafia boss who comes, in vain as it turns out, to call Salvo back to to do his duty, and kill.

But first of all Salvo (no name though till much later, when Rita, the blind girl, asks for it), a bodyguard, is cornered by some rival assassins on a road, and captures one and forces him to say who set them on him ("Renato") then executes the man. The scene shifts to Renato's house (darkened against the Palermo heat) and a long remarkable single-take sequence focused on Rita, at first sitting at a table listening to her favorite song, "Arriverà" by the Modà and Emma, and happily counting money, then gradually realizing that danger and death have invaded, and moving around gradually in growing terror. Remarkable sound design, light (dim, yet revealing), and acting by Sara Serraiocco introduce us at perhaps slightly overindulgent length to the sheer sensuality of this film and its ability to convey an unusual point of view. At this point, Renato is not there. Hence the waiting.

Then Renato comes and the killing takes place, though we don't see it, because we're still with Rita. Somehow Salvo can't bear to treat her as necessary collateral damage, and keeps her a prisoner. Boyd van Hoeij gives an excellent (and justifiably admiring) description of all this in his Cannes Variety review. It's virtuoso work that, even if Grassadonia and Piazza don't gain a wide audience with this offbeat debut, will guarantee them attention from cinephiles in future both for richness of technique and originality of concept. And when von Hoeij says, in the traditional Variety lingo, "Tech package is simply superb," these are not idle words.

However von Hoeij is unfortunately also right to suggest the second half doesn't wholly mesh with the first or match its originality. This long finale ranges between the dingy apartment and an abandoned factory warehouse where Salvo's keeping Rita prisoner, and then on to an escape when a bunch of mafiosi associates come and boss Mario Pupella orders Salvo to finish her off. This whole second half feels a bit like back-peddling, especially considering the high energy and physical intensity of the earlier section. But the finale scene is wonderfully iconic and austere.

Screening for this review as part of the New Directors/New Films 2014 series (of MoMA and the Film Society of Lincoln Center) one had the feeling that the press and industry audience had a very mixed reaction, some obviously unsatisfied, others simply not knowing quite what to make of it. But parts of this film are clearly brilliant and highly original. Salah Bakri is riveting. He isn't as handsome as the young Delon but he has the stoical assurance, upright bearing, and ability to hold the screen in thrall. And Sara Serraiocco's blind act and transformation into a beautiful sound young woman keeps pace with Bakri's mysterious strength. Given the generally low blood pressure of contemporary Italian cinema, anything this original and assured is good news. What the directors do from here forward we'll have to wait and see.

Salvo, 104 mins., debuted at Cannes May 2013 where it won the Critics' Week grand prize. A French and Italian co-production which Jeanne Moreau had something to do with. In the US it's a Film Movement release. Released in France 16 Oct. 2013 with a good critical reception (Allociné press rating: 3.4) and Les Inrockuptibles loved it, but Cahiers thought it too showoff-y, more a directors' calling card than a film; and others argued (not without reason) that it lacks narrative backbone. It was screened for this review as part of the FSLC-MoMA series, New Directors/New Films, showing Sat. 29 Mar., 2014 at 9pm at MoMA and Sun. 30 Mar. at 4pm at Lincoln Center.

SALEH BAKRI IN SALVO

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-31-2014 at 09:05 PM.

-

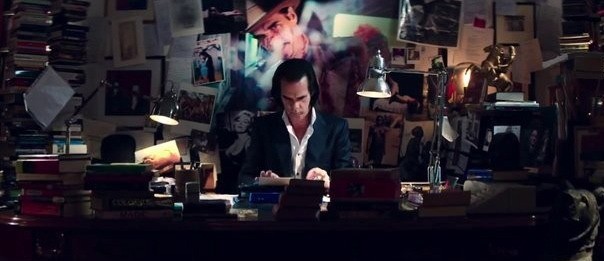

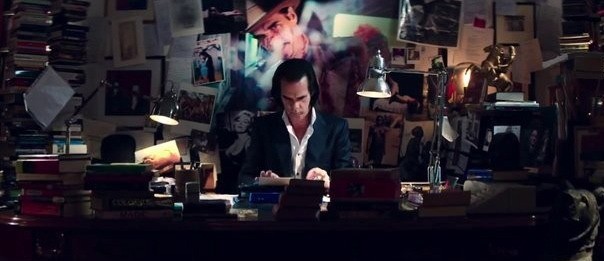

20,000 DAYS ON EARTH (Ian Forsyth, Jane Pollard 2014)--ND/NF

IAN FORSYTH, JANE POLLARD: 20,000 DAYS ON EARTH (2014)--ND/NF

NICK CAVE WRITING ON HIS TYPRWRITER IN 20,000 DAYS ON EARTH

An immersive fiction-stye self-portrait by the Australian Nick Cave

For those wanting or needing a fill-in on Nick Cave, the Australian-born, long UK-resident singer-songwriter, there will be some gaps after watching this film, but it makes up for that in a nearly non-stop visit with the man, who, collaborating with writer-directors Ian Forsyth and Jane Pollard, wisely eschews the conventional vintage tapes and straightforward bio in favor of a Shandean tale enabled by lots of talk about himself in the present time, semi-magical, noir-ish conversations with old friends (including Ray Winstone and Kylie Minogue) and wife in the light tan leather seats of his black Jaguar (as he drives around his chilly wet resort town of Brighton), expounds to a shrink, and visits his archive where attendants go through photo files and he identifies himself at various stages, in elementary school, in grammar school, in his tiny hideaway in Berlin. It's an elegant fiction-style film worthy of the man's originality, intelligence and wit. It culminates with "climactic concert footage of Cave and the Bad Seeds performing explosive renditions of 'Higgs Boson Blues,' 'Jubilee Street' and 'Stagger Lee' at the Sydney Opera House," "well timed to allow for catharsis after so much formal control and highbrow talk" (Rob Nelson, Variety). And this segment, it might be added, cunningly inserts some split-second overlap-clips showing Cave performing similarly at earlier stagesof his now considerable career.

The sessions with the shrink are artificial and expository. It may be said that nothing is more static cinematically than exposition constructed via shrink sessions; yet they were used in "The Sopranos" with success and added interest and contrast there. Cave tells the shrink his father died when he was 19. He does not say he learned of the death from his mother as she was bailing him out of jail for burglary; that it was the time in his life when he was most confused. "The loss of my father created in my life a vacuum, a space in which my words began to float and collect and find their purpose," he has said. This comes through in the film: like so many of us, he wove meaning out of confusion through writing.

He notes to the shrink that he was a drug addict, which he was told was a dangerous way to behave. He also recounts that his father read him the opening chapter of Nabokov's Lolita when he was a young boy, an important moment of rapport. He composes the lyrics to his songs tapping on a small manual portable typewriter. The results are cut out and pasted into a notebook he props up on a piano to sing them. He dresses in the same dark suits to walk around and perform on stage. His present wife when he first saw her (he recounts this as she sits in his Jaguar behind him) embodied all the movie stars and models and divas and beauties in history and paintings he'd ever seen.

There is a wealth of music in the background, but this is not a music film, rather a film about a musician and writer. (He penned the script of the striking Australian film The Proposition, though this is not mentioned.)He is shown, using the collaged notebook of lyrics, with his musicians the Bad Seeds recording their 2013 album Push the Sky Away, and here we see he composes quite interesting words. But this moment, of interest to viewers learning consciously of Cave's lyrics for the first time, does not arrive till 50 minutes into the film.

The film does not discuss the extremely eclectic nature of Cave and his various groups' music, nor name or date his earlier groups (though with his current group they mention a line he's singing sounds like Lionel Richie, which sounds plenty eclectic). It does not say when he moved to England (in 1980, when he was 23) or why. It doesn't mention that he has written novels. It mentions his twin sons born with his current wife former model Susie Blick, but it does not mention his other sons by two other women, or the six years after his time in West Berlin when he lived in São Paulo, Brazil, where he was married to Brazilian journalist Viviane Carneiro and had a son, Luke.

In short, this is not a thorough review of Nick Cave's life and work. It is, however, an artistic and engaging portrait of the man that fans and others may enjoy. But "While the film is seemingly accessible as a portrait of an artist who seems particularly attuned to his own creative process, and particularly adept at describing this attunement, it's unlikely that many who aren't already whole-hog Bad Seeds fans would be able to stomach much of Cave's self-styled pomposity" (Slant Magazine). This comment is a bit unfair: he is humorously self-aware about his self-centeredness, noting that in an old mock-last will and testament he provided that all proceeds from his estate were to go to "The Nick Cave Memorial Museum."

Some of Cave's generalizations about the creative process in the film are rather over-general and obvious. But his opening statement about how you compose a song is interesting as a talking point. "Songwriting is about counterpoint," he says, "like letting a child into the same room as a Mongolian psychopath or something." He suggests a song (the lyrics that is) brings together two unrelated and contrasting things, and sometimes a third thing. This resembles the famous definition of surrealism as "the random encounter between an umbrella and a sewing-machine upon a dissecting-table."

20,000 Days on Earth , 95 mins., is a Drafthouse Films release. It debuted 20 Jan. 2014 at Sundance. It was screened for this review as part of the FSLC-MoMA series New Directors/New Films, of which it is the closing night film showing Sun., 30 Mar at 7 pm and 9:30pm. at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. This film will be distributed by Drafthouse Films with release date 17 September 2014.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-31-2014 at 09:00 PM.

-

Selects

Selects

FEBRUARY 17-27 2014 PUBLIC SCREENINGS

MARCH 19-30 2014

PUBLIC SCREENINGS

Rating New Directors/New Films 2014; comments on Film Comment Selects

Though New Directors features some provocative and radical new work, some of the films, the best, were straightforward dramas that had resonance with our times of worry, paranoia, and economic and environmental crisis. Top marks to the two Romanian features, The Japanese Dog (Jurgiu ), the story of a father devastated by flood reunited with his expatriate son, and Quod Erat Demonstrandum (Gruzsnetczki ), a tale of Eighties intellectual repression, which are not groundbreaking in technique but simply well-made and relevant films. A sparkling Chinese debut was Trap Street (Qu), a romance with a nod to government oppression. The Israeli Youth (Shoval) is a kidnapping thriller full of economic and job desperation. The Italian Salvo (Grassadonia, Piazza), with impressive performances and virtuoso technique rings changes on the mafia thriller, blending in a doomed romance and exalted spaghetti western style, another strong debut. There were a couple of powerful documentaries: Return to Homs (Derki), following young Syrian rebels up so close the filmmaker risked his life constantly, is an absolute must-see; We Come As Friends is another important statement about the exploitation of Africa, South Sudan this time, but not as coherent as Hubert Sauper's earlier Darwin's Nightmare.

Other New Directors films were certainly worth seeking out, such as Ayoade's The Double, a polished Brazil knockoff, but not as great and warm as Ayaode'sSubmarine. Obvious Child (Robbespierre) is a successful US female comedy; Salvation Army (Taïa) is a beautifully stark, pioneering gay film from Morocco. And there are many other more radical titles of interest for various reasons that are what give the series its depth and character.

This is still a great series and it was a great pleasure and an honor to be able to watch every one of the feature-length selections. Special thanks to John Wildman FSLC Senior Publicist and David Ninh Publicist for all their help in covering the series and keeping it running so smoothly; to all the staff at the Film Society and MoMA; to Glenn Raucher of the Film Society, Theater Manager, who keeps the theaters providing world class screening quality.

I liked the Film Comment Selects titles I chose, Felony (Saville), Me & You (Bertolucci), Cherchez Hortense (Bonitzer), Our Sunhi (Hong), but can't list "best of" this series because as before, it was impossible to sample a large enough chunk of this more eclectic and chronologically free-ranging series.

FSLC Programming Director Dennis Lim

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-01-2015 at 05:40 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Selects

Selects

Bookmarks