-

Andrew Bujalski: COMPUUTER CHESS (2013)

ANDREW BUJALSKI: COMPUTER CHESS (2013)

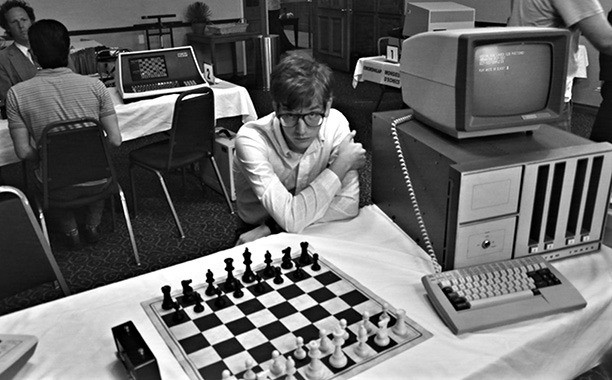

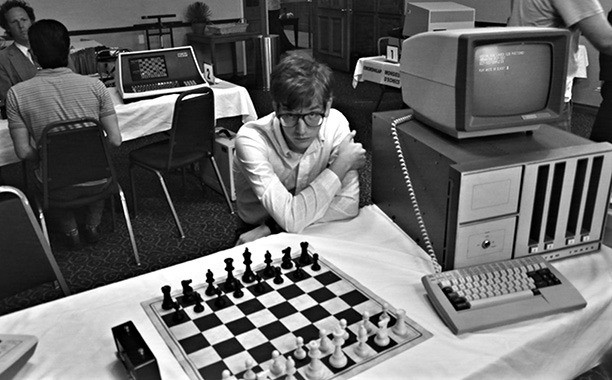

PATRICK RIESTER IN COMPUTER CHESS

Terrifyingly nerdy

Mumblecore "godfather" Andrew Bujalski (Mutual Appreciation, Funny Ha Ha, Beeswax) takes a new tack in his latest film, Computer Chess, away from his own generation and time into a moment that might seem for him resonantly, awesomely prehistoric. He reconstructs (or invents?) a weekend circa 1980 computer chess convention long before the sleek age of smart phones and Mac Airs. To do this he uses a combination of improvisation, studiously bad hair and unfashionable clothes, and ancient Portapak videotape equipment, mimicking the shooting style that goes with this technology, thus recapturing in the round a scary nerdiness. The result can seem brilliant -- or totally stupid, depending how you look at it. The cult potential of this film is unquestionable. It is instantly recognizable as unique. It may not initially be a whole lot of fun to watch -- unless, that is, you're consciously filtering it through Pynchon and comparing it favorably with Pablo Larraín and and Harmony Korine, which not all viewers will manage. Distinctly odd this certainly is, one of the year's most original American films; and conceivably a bold new step for Bujalski to greater scope and a wider audience.

But this is a movie that will polarize audiences. When it showed at Sundance "squares" like Hollywood Reporter's Todd McCarthy ("deadly dull") and Variety's Justin Chang ("Hit or miss") dutifully noted the singularity and authentic look of the film but didn't particularly like it. "Hipsters" like Mike D'Angelo ("78/100, "Deeply, deeply, deeply weird"--it's now no. 2 on D'Angelo's year's running ten-best list) and Vadim Rizov ("major filmmaking") on the other hand were thrilled to the core. (These were January, pre-release, reviews.)

As so often the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Both sides acknowledge the spot-on evocation of period (even though that period's a bit vague). The consciousness-raising est-like meetings (with a dash of group sex) also happening at the dinky hotel that weekend could be well before 1980 and Spotpak cameras go back to 1969. The bad hair and clothes and sexism evoke something like thirty years ago well, as does the fuzzy black and white video (Bujalski's ironic response to chiding about when he would move to -- modern -- video from 16mm. film).

But authenticity and bad acting are not the same: they may come close, but they will never meet. It's also true that the humor here falls flat, and if this isn't a comedy what is it? Computer Chess is original but also a long slog whose cringe-worthiness peaks when the middle-aged couple try to lure the shyest, youngest programmer Peter Bishton (Patrick Riester) into sex with them. The pervasive nerdiness has a terrifying way of making you feel it's entering you and becoming you and reflecting everyday life more than any other movies do.

And there is the meta-fictional realization that all this "realism" is highly stylized. In fact what's lacking are the one or two cool guys who'd set off the gang of nerds and make them nerdier, as a drop of black paint is said to make a gallon of white paint whiter. But everybody thinks this seems like real found footage. It does -- sort of. And one does appreciate what the Guardian writer Andrew Pulver admiringly noted, "a wide-eyed appreciation for just what humble, shabby beginnings the digital revolution sprang from."

Real computer programmers and various personalities participate as cast members in Bujalski's geek game along with huge clunky period computers with clackity keyboards and black screens spewing rows of white digits. They are outsized -- but still not capable yet by a long sight of beating a living human chess master. As A.O. Scott notes, "the triumph of I.B.M.’s Big Blue seems a very long way off." The program of the event is to pit various rival computer chess programs against each other in playoffs, and at the end the winning program gets to play against a human, the arrogant conference leader Henderson (played by academic and film critic Gerald Peary). Some programming team heads like the experimental psychologist Martin Beuscher (Wiley Wiggins) coyly vaunt their personal aims and methods. Others, like Shelly Flintic (Robin Schwartz), repeatedly touted as the tourney’s first female participant, or the shy and possibly brilliant youngster Peter, hover mutely in the background. The boastful and evidently disliked Michael Papageorge (Myles Paige) is for no good reason forced to wander the hotel at night searching for a room. A skinny call girl hovers in front. In a mystical sci-fi touch, Peter thinks the computers have souls and the one he's involved with is failing because it doesn't want to play against another computer but against a human. The goofy, invasive free love encounter group conference, led by a tall black "African" Papageorge thinks may just be from Detroit, is an obvious contrast, and helps round out the sense of period goofiness. The plump lady who tries to seduce Peter says he'll never reach his "true potential" if he sticks to programming or the 64 squares of a chess board -- and so on.

Sudden split screens interrupt the otherwise period video images, which as has been pointed out are more consistently dated in visual style than the use of Sony U-matic cassette video cameras in Pablo Larraín's No. For a few minutes in an unrelated scene of Papageorge at his mother's, Bujalski reverts to blotchy color film. If you have seen the documentaries about the human-computer chess wars (notably Kasparov vs. Deep Blue) you will miss here any depth or excitement in the snatches of games that, as Todd McCarthy wrote, "are excerpted in ways that offer no insight or, God forbid, tension." In fact Bujalski's deadpan humor here bets on deliberately letting everything fall flat. That's the point.

There is much to ponder here, perhaps most resonant being the idea of a crowd of geeks and nerds who don't yet know they are to rule the world and of a burgeoning technology that now looks ridiculously primitive, reminding us how ruthless progress is and how clunky and limited present technology is likely to look thirty years hence.

Now that the film has had its July US theatrical release and will get more widely reviewed, awareness of it is likely to spread; and it has had time to percolate in my mind as something memorably unique. They don't make 'em like this any more (if they ever did). A.O. Scott of the NY Times describes Computer Chess as "sneakily brilliant" and ends, "Artificial intelligence remains an intoxicating theory and a heady possibility, about which I am hardly qualified to speak. But I do know real filmmaking intelligence when I see it." Aaron Hills of the Village Voice calls the film "So far the funniest, headiest, most playfully eccentric American indie of the year." In five months or so he may want to drop the "so far."

Computer Chess debuted at Sundance (surprisingly, a first for Bujalski), in its "Next" section. It was also shown at Berlin, Montclair, the SFIFF (the latter where it was originally screened by me). US theatrical release (at Film Forum, New York) was July 17, 2013.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:30 AM.

-

Ramon Zürcher: THE STRANGE LITTLE CAT (2013)

RAMON ZÜRCHER: THE STRANGE LITTLE CAT (2013)

Leon Alan Beiersdorf and the cat in The Strange Little Cat

Kitchen life: choreographed poetry and zaniness of the quotidian

The quiet magic and lurking humor of the quotidian are subtly dramatized in this seamless film about several generations of a good looking family puttering around the a kitchen of a Berlin apartment. Two dozen people and creatures come and go, including a black dog, an orange cat, and a moth (which keeps coming back). A rat is also mentioned. Comparisons with Jacques Tati, Michel Gondry, and François Ozon have been made. Zürcher is only 30; the film is only 72 minutes long. Accomplished filmmaking, though conventional expectations are frustrated and the hilarity of Tati is certainly missing. My memory is the sort of obligato of the presiding figure of the kitchen and the film, the unnamed mother played by Jenny Schily, whose Sphinxlike face reminded me of Charlotte Rampling's. For those who can't tune in -- and small English subtitles that vanish in a millisecond may undermine those efforts -- this may seem much ado about nothing. But the originality of the conception and the precision of the execution are unmistakable and critics at the Berlinale ranked this film high.

First a cat loudly whines to be let in, and then that seamlessly morphs into the voice of the youngest child, Clara (Mia Kasalo), who likes to screech at kitchen appliances. Zürcher works with what there is, so there are electric blackouts, a noisy espresso machine, a bottle that magically spins in a pan, and a washing machine, briefly menacing, repaired by a handsome neighbor with whom Schilly's character has a wordless sexual chemistry. There is a shopping list whose orthography is much discussed as a recurring family record of childhood, and people come and go. Zürcher's art is in the smooth choreography of the many people moving around and dodging each other (or kissing later when another group visits for the long prepared for dinner that evening), constantly talking, sometimes seen from below, constantly in action, as if naturally, yet with a perfection, a geometrical rhythm, that suggests preparatory diagrams and many rehearsals -- but the effort never shows.

There are recurrent motifs: the moth reappearing, the ginger cat slinking in and out, the dog coming and going, arguments over buttons and shirts, "grandmother's sleeping!" said to quiet noisy children. Cheery music by San Francisco rock trio Thee More Shallows ("a shiny chamber-orchestra affair in sub-Michael Nyman vein" explains Stephen Dalton in Hollywood Reporter) helps keep things light and smooth.

Zürcher is interested in interrelationships and overlappings, both familial and physical. Sometimes people briefly recall a recent incident, which bears this out. For instance Schilly's character recalls going to a movie with grandmother, when a man who sat beside her put his right foot over her left one. She didn't know that it was intentional: maybe he was just too engrossed in the movie to notice he'd done it. When she didn't pull her foot out right away, she was stuck and had to leave it there, as grandmother fell asleep and breathed heavily, making her fear she'd snore. Finally grandmother woke up with a start and she could retract her foot. Zürch sees his scene and perhaps life as a kind of "Twittering Machine" like a Rube Goldberg gadget only less eccentric. He has been for some time and still is a student at the DFFB Berlin film school, and made this film reportedly as a result of a seminar with Béla Tarr, whom he thanks in the credits.

Zürcher was "The first-timer with perhaps the most distinctive sensibility" at Berlin this year, wrote Dennis Lim in the NY Times. His unmistakable talents may show to even better effect in future if he relaxes a little and lets things get simpler, but it seems essential to his effect to give equal weight to everything, people, animals, and objects, "such that nobody and nothing is sidelined," as Charles H. Meyer writes for Cinspect.

Das Merkwurdige Kätzchen, 72 mins., in German, debuted at Berlin. The Swiss-born filmmaker, now resident in Berlin, has made videos. This is his first feature.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:31 AM.

-

Justine Malle: YOUTH (2013)

JUSTINE MALLE: YOUTH (2013)

ESTHER GARREL AND ÉMILE BERTHERAT IN YOUTH

A girl's shaky coming of age, her famous father's death

A short feature debut at only 75 minutes, Youth/Jeunesse is more or less 39-year-old Justine Malle's much-delayed memoir of her father director Louis Malle's last days and her shaky coming of age at twenty when he rapidly declined after being diagnosed with a brain-destroying virus. It's also a homage to the Nouvelle Vague style, with its simple mise-en-scene, sweeping drives through the country, and rapid-fire notations of temporary romances, Youth has a classic simplicity and contains beautiful, touching moments perhaps worthy of the filmmaker's illustrious father, but in important ways it also disappoints. It's no coincidence perhaps that Juliette, Justine's alter ego, is played by Esther Garrel, daughter of director Philippe and sister of Louis Garrel. They have things in common.

Esther embodies the protagonist's mixture of defiance and immaturity up to a point. She has her brother's strong Mediterranean face, if no quite his presence and charisma. The younger male leads being pretty generic, it says something that the best work may be by Didier Bezace, an actor who's rarely even had serious talking roles in films. Though his on screen moments are few -- this is still more about the girl -- Bezace is touching and technically convincing in portraying the rapid physical and mental decline of her father. Whether he has the presence of Malle, however, is doubtful.

Juliette's father is superficially so like Louis Malle he made a documentary in India (there is even an excerpt shown), and had two other children with different mothers. Malle died in California with Candice Bergan, however; this Papa's current spouse is Portuguese and they live in the French countryside (the actual Malle estate is used). Juliette has an on-off relationship with a classmate, Benjamin (Émile Bertherat of LOL), who refuses to have sex with her when he learns she's still a virgin ("I need things to be simple; if not it makes me nervous"), but then relents, for one time. Juliette seems to like his coldness and failure to make a fuss over the tragedy of her father's impending demise, which she at first is in denial about, and then avoids being present for his very last days.

I have to concur with Screen Daily's Dan Fainaru, who says the references to Iranian cinema and Eric Rohmer and to fashionable songs and to Leibnitz and Nietzsche and the shots of hip left bank cinemas like the Saint André des Arts and the Champollion ("Le Champo") evoke a New Wave-ish flavor in a rapid catalogue without integrating them "into the fabric of the plot." The director, who co-authored the script with Cécile Vargaftig, might have done better to keep things simpler and go into more depth. She may be ruthlessly honest in representing herself as unformed and a bit cowardly at twenty (a little step-sister seems better and more sensible at caring for her father), but this vague protagonist may not be the best lens through which to view these events.

Unfortunately this film is content to be more a series of sketches than the kind of searching and precocious work one has seen from Mia Hansen-Løve, the outstanding young French woman director, who is seven years younger. Hansen-Løve's The Father of My Children, while not autobiographical, but based on the life of her mentor, the influential French producer Hubert Balsan, is a richer study both of a cinematic father figure and of a family.

Jeunesse, 75 mins., has had showings in Italy (at Rome's Alice nella città sidebar) and Denmark, and is included in the New Directors competition of the San Francisco International FIlm Festival (showing 1, 4, and 5 May 2013), where it was screened for this review. It opens in France 3 July.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:31 AM.

-

William Vega: LA SIRGA (2012)

WILLIAM VEGA: LA SIRGA (2012)

JOGHIS SEUDIN ARIAS IN LA SIRGA

Political unrest embodied in wind and water

This boldly abstract debut film, well received at Cannes, an award-winner at Lima, nominated for a Discovery Director Award and FIPRESCI at Toronto, emphasizes windy sound and wild open spaces over story: it's a mood piece, magical if you give yourself to it, richly if vaguely evocative. A teenage Colombian refugee, Alicia (Joghis Seudin Arias) is a downcast young woman who sleepwalks, tries to rebuild her life at a guest house located on the shores of a great lake in the Andes in William Vega's atmospheric, quietly haunting film. She is running from the burning of her house and killing of her parents by unspecified hostile forces. Alicia spends her days working with Flora (Floralba Achicanoy), with her uncle Cesar (Julio Cesar Roble) and his son Freddy (Heraldo Romero). No one is very friendly and everything is tenuous but perhaps her greatest ally is Mirichis (David Fernando Guacas), a man who does errands on a boat and wants to go away with her. All is uncertainty ("I don't know" is the main answer to questions) and I never believed these people had real identities or functions; it's all about metaphor, the dilapidated inn representing Colombia itself. But the place itself, the vast quiet lake and swampy borders and big plants, is also all very real.

Menace and uncertainty vie with solitude and emptiness. Vega opens with the image of a dead man hung on a spear, a reference to the horror Alica is fleeing from. La Sirga (it means "The Towrope"), the "inn" Cesar watches over, seems more like a multi-layered shack fully of cracks and holes letting in the rain and howling wind, and we never get a precise idea of its upper storeys. The "restoration" Alicia, Flora, and for a while Freddy work on is vague, involving sheets of plastic, varnish, and potted flowers set around on the front porch. The idea of "Tourists" seems fantastic; there is no one around for many miles. Vega is deliberately waiting and revealing nothing of what may come to pass: but the hidden subject is danger and corruption, a national "house" that isn't safe to visit or really stable. There's something clearly hard and menacing about Freddy, and both he and Uncle Oscar spy on Alicia at night through the omnipresent chinks in the walls: no privacy, no stability, no future, no hope.

Sound and image (by dp Sofia Oggioni Hatty) are excellent, and use of location is seamless and mysterious. This is one of these things where you wonder how the filmmakers ever got there, and the location is what you remember most.

La Sirga, 88 mins., a Colombia, France, Mexico co-producion, debuted at Cannes, showed also at Toronto and San Diego, Chicago and Boston, many other locations, and included in the San Francisco International Film Festival, in connection with which it was screened for this review. To be released in the US by Film Movement. French release is set for 24 April 2013. US DVD release 6 August 2013.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 02:59 AM.

-

Belmin Söylemez: PRESENT TENSE (2012)

BELMIN SOYLEMEZ: PRESENT TENSE (2012)

Senay Aydim and Sanem Öge in Present Tense

Quiet desperation in Istanbul

Documentary filmmaker Belmin Söylemez focoses in her beautiful, atmospheric feature debut on an enigmatic woman called Mina (Sanem Öge), recently divorced and living alone in Istanbul, who dreams of escaping to the US, though there is an air of patient hopelessness about her. She is about to be evicted from her apartment (the building is being turned into a hotel) and at the film's start works as a cipher in some big office. She gets a job as a fortune teller in a cafe reading coffee grounds and in this setting, is befriended by the owner Tayfon (Ozan Bilen), and another employe, Fezi (Senay Aydim), who are both as much adrift as she is. Through these associations and her fortune telling she begins ruminating about her past. People come and go; a recurrent trope of the film is the fortune telling. Mina's good at it; women often are pleased with her descriptions of their lives and like her, inviting her to private sessions. If only she could see into her own problems as well as she sees into other people's.

Söylemez constantly hovers around her protagonist, who projects a subtle blend of determination and exhaustion, with hints of other aspects, a serious accident as a child, poor relations with other family members. What little money she accumulates she puts into dollars, but she hasn't the documents or other requirements for study-travel to America and she floats in uncertain limbo.

Söylemez shows some influence of Iranian films. Her first documentary feature, the 2005, 34 Taxi, depicting Istanbul through cab rides, could be an idea of Kiarostami's. Here the screenplay written by the director and Hasmet Topaglu conveys a strong sense of urban ennui and alienation, and with it, to leaven the glumness, a pleasing mystery. And it doesn't hurt that as Jay Weissberg of Variety suggests, Sanem Öge looks a good deal like the young Juliette Binoche. He also rightly compliments Austrian dp Peter Roehsler whose work here is a continual pleasure to watch, for "his stately, mutedly rich lensing," in which figures together, sitting at the cafe to talk, say, are often framed formally and distantly "to gently emphasize their separation." The color Roehsler captures is delicately beautiful too, with much emphasis on yellow, turquoise (the word may come from "Turkey") and pale green, and there are many shots of the wonderfully complex bottoms of Turkish coffee cups: the possibility of seeing all the world in those scattered and hardened grounds has never been more evident.

Present Tense/şimdiki zaman, in Turkish, 110 mins., debuted at Sarajevo (April 2012), and was shown at Istanbul, where Sanem Öge was given the Best Actress award, Hamburg and Turin. It is included in the April-May 2013 San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review.

Present Tense won the New Directors feature award at the San Francisco International Film Festival.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:34 AM.

-

Mike Ott: PEARBLOSSOM HIGHWAY (2012)

MIKE OTT: PEARBLOSSOM HIGHWAY (2012)

ATSUKO OKATSUKA IN PEARBLOSSOM HIGHWAY

Looking for dad, missing grandma

Mike Ott is a skilled super-indie American filmmaker who gets at the heart of being an off-the-radar young American partly by introducing foreign characters, and his last two films are both set in "the buttcrack of the Antelope Valley" (Doug Harvey), a poor-white stoner small town California desert world. Both also feature the sweet, touching Cory Zacharia and his co-writer Atsuko Okatsuka in the lead roles. In fact it's a bit confusing to watch Ott's 2010 Littlerock, his second feature, in close proximity with his new on Pearblossom Highway because of the way characters and situations overlap without being quite the same. In both, Ott deftly uses his simple methods and materials to deliver something touching and authentic. They're both good, though Littlerock may leave more of an emotional wake behind it and have a more clear and present time sequence.

In Littlerock, Atsuko (her character's name too) and her brother meet Cory (Cory Zacharia) and his friends while visiting from Japan and on their way to San Francisco and Manzanar. Only the brother speaks any English, and the linguistic non-understanding is a brilliant study in point of view. In Pearblossom Highway, Atsuko has become Anna, who has no brother, is living in California, speaks English, is preparing for a citizenship exam, misses her grandmother, and sells her body to pay for a visit home. Cory (same name) is her best friend (as he wanted to be in Littlerock), sort of, and is about the same person, only it's a couple years later and he's recently had a DIY conviction -- he drinks and smokes drugs too much -- and his life is a mass of artistic plans that aren't happening. And instead of talking all the time to the uncomprehending Atsuko, he talks into a video diary, expressing doubts and aspirations, where it's often hard to tell whether the actor is talking about his character or himself. This film is punctuated by jarring video-game shot sounds: it's intentionally more disjointed than the previous one. In Littlerock Cory wanted to go to L.A. and become a model and an actor; now he makes videos, works part-time for his stepfather, is the lead singer in a death metal band called Cory and the Corrupt, and wants to get on a TV reality show, "Young People." He's the one who has a brother this time who takes Cory and Anna to San Francisco to meet Cory's biological father. Anna's emotional story is told through phone calls to Japan. She hasn't the money to go there but her grandmother may be dying.

Some of the other cast members reappear too, a handsome, maybe not so nice black guy, Markiss (Markiss McFadden), and a Latino man, Francisco (Roberto 'Sanz' Sanchez) whose first name and role changes, and who, like Okatsuko's character, speaks perfect English now but in the previous film was a short-order cook who couldn't understand much outside the kitchen. He seems at home explaining things to Atsuko (in Littlerock) in Spanish, while she replies in Japanese. All through Littlerock Cory talks constantly and caringly to Atsuko in English, and she replies in Japanese, neither understanding exactly what the other one is saying.

Ott is good with transitory, superficial relationships. Rarely as in Littlerock has anyone captured so well how people, young ones anyway, can become friends and even lovers for a few days, and then drift apart. And maybe the relationship between Atsuko and Cory is the most touching one he captures. As Doug Harvey noted, Anna and Cory may only really connect while watching a Chaplin movie at the Roxie in San Francisco. The hunt for his father with his macho, disapproving older brother Jeff (John Brotherton ) leads to Cory's conclusion in his video diary that in the end, it "wasn't that interesting." Doug Harvey thinks Ott's channeling the French New Wave and calls Cory Zacharia his Jean-Pierre Léaud. Harvey makes great claims for Ott, and I don't know if they're all justified, but his use of and collaborations with his little troop of actors and writers is successful and ongoing. Lake Los Angeles is coming in 2014, with the same writing team and some of the same actors and characters. This seems like American indie filmmaking at its best and most humanistic.

Pearblossom Highway, 78 mins., debuted at the Viennale, following at AFI and other festivals, including the San Francisco International Film Festival in May 2013, where it was screened for this review. Littlerock got much fest attention including an Independent Spirit Award and a Gotham award that included a NYC theatrical release, followed by pickup by Fox Lorber: it is on DVD and instant play at Netflix. Pearblossom Highway was partially funded by the San Francisco Film Society.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 03:01 AM.

-

Michel Franco: AFTER LUCIA (2012)

MICHEL FRANCO: AFTER LUCIA/DESPUÉS DE LUCÍA (2012)

TESSA IA IN AFTER LUCIA

Bereavement, bullying, blowback

It's funny to go from Mike Ott's very natural and organic American indie films Littlerock and Pearblossom Highway to one that's completely self-conscious, contrived, and staged. An IMDb viewer's suggestion that Franco is a "new Mexican Haneke" is going overboard. He lacks Haneke's boldness and mastery, and this doesn't seem like a Haneke topic. Franco may deserve credit for depicting the nastiness of bullying with chilly thoroughness. Either this is a newly widespread phenomenon or there's a newly pervasive awareness of it. "Bullying" -- the English word is used also in other languages for this hot button topic. If Después de Lucía is to be believed, it's just as ugly at upscale Mexico City high schools as in the United States. This won the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes (jury headed by Tim Roth) and was Mexico's entry for the Best Foreign Oscar of 2013. But I have reservations about it. It's an example of taking one idea and hitting on it over and over relentlessly, except for a morally dubious finale that caters to the worst impulses in the audience, and there are elements that seem implausible. Ultimately despite its rubbing our noses in cruel teen behavior for a while, this film doesn't so much fully develop the theme of bullying and its consequences as use it, to cite Charles Grant of Variety, as "an attention-grabbing hook."

Lucía is the wife and mother, dead in a car accident. Her widower (Gonzalo Vega Jr.), a successful chef, and their teenage daughter Alejandra (Tessa Ia), move from Puerto Vallarta to Mexico City to a new restaurant (for him) and a new posh school (for her). They're cut off from emotion, he especially, but then according to Letterboxed contributor Preston, Franco may have started off meaning to do something "sober" and then been "carried away by the more sensational aspects." This seems unlikely but the parts don't quite fit. Others (back to IMDb) suggest the first 40 minutes are just deadly dull and could be lopped off. Alejandra falls in quickly with the in crowd at school (but we know those seek victims) and is doing well; her father plainly isn't. But then Alejandra gets drunk at a party and has sex with the alpha girl's boyfriend José (Gonzalo Vega Sisto), which he cellphone-films. It goes around the school, and the attacks begin, gradually escalating and peaking on a school trip to Veracruz -- a surprisingly boozy and druggy one (one of the implausibilities) given that it's a school trip and the school has rigorous drug tests. At first "Alé" fights back vigorously to her tormenters but she becomes more and more meek and passive, borderline catatonic on the trip. Due to her dad's having a hard time, she tells him nothing till things get quite advanced.

Then things take several new directions, essentially dropping the social issue of bullying for other outcomes, partly unexpected. Franco maintains cool art house style with diegetic sound, no music, a measured pace, avoiding conventional mainstream appeal. The effect sometimes is to make shots uninformative. Certain group scenes of the kids seem unconvincing, the non actors, reportedly some of them Ia's real life classmates, perhaps not well directed; and some of the scenes shot from the middle distance aren't wholly clear. However the latter part certainly deserves credit for being surprising and exciting, especially compared to the beginning.

Después de Lucía, 93 mins., debuted at Cannes as mentioned May 2012, included at a number of major festivals including London, Glasgow, and Rio with releases in various countries, including France (critical response fine: Allociné press rating 3.7). Also included in the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review (showing 26 and 29 April 2013).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:35 AM.

-

Marcel Gisler: ROSIE (2013)

MARCEL GISLER: ROSIE (2013)

Fabian Krüger, Sibylle Brunner and Sebastian Ledesma in Rosie

Dealing with family problems opens up the heart of a cynical writer

Rosie is a slightly clichéd theme: the cynic who finds love and becomes reconciled to his past. It's all handled in such an understated way that the filmmaker (who co-wrote with his previous collaborator Rudolf Nadler) carries it off, but the energy level is never very high. It's fueled by Sibylle Brunner as the mother, Rosie, a feisty old dame who drinks and smokes too much but maintains her independence even in the face of old age's indignities. Brunner's performance is pitch-perfect, scene-stealing at moments yet still mostly understated. Rosie and her jaded gay novelist son Lorenz (Fabian Krüger) share a cigarette and glass of wine now and then. If fact everybody shares a cigarette and a glass of wine now and then. Rosie's defiance gives her a twinkle in her eye sometimes. Indeed sometimes she's outrageous. At those times she's probably drunk. In fact she's an alcoholic. Lorenz and his sister, the grumpy, troubled Sophie (Judith Hofmann) frown at this, but tolerate it. The story is about everybody coming together, a bit. Rosie is about facing life on life's terms, but it's not made to look so terribly hard.

The thread that makes this a gay movie, but less overtly so than Gisler's previous films, is Mario (Sebastian Ledesma), a handsome, soulful young man who turns up eager to have sex with Lorenz. He's been a huge fan of his novels since he was a kid. Lorenz, a veteran of one-night stands, cooly chronicled in his books, does go to bed with Mario once -- despite back trouble -- but will have none of the youth's clinginess. Besides, he's dealing with Sophie, Rosie, and his agent. He's supposed to be on a book tour, or something. The film's transitions are usually shots of drives along the highway, accompanied by classical music. Frankly, if you don't know the landscape, they don't mean much. Presumably Lorenz has to go back and forth to Berlin, but it's not clear.

You don't quite know whether to root for Rosie or shake your head. Sure, tippling and smoking all day are her ways of having a good time, but there's something a little sad about her. And about Sophie.

A lunkish girl called Chantal (Anna-Katharina Müller) turns up who does chores for Rosie. Then despite Lorenz's having rebuffed Mario, he turns up helping Rosie too, in time to give Lorenz a very loving back rub. Lorenz is twenty years older than Mario, but Fabian Krüger is handsome and youthful. He may need the bad back to show he has some age. In the course of things, Rosie takes several gradual turns for the worse. And there's news from the past. At a birthday dinner for Rosie, an old man appears, a friend of the family, it seems. Lorenz looks into his history with Rosie and his father (about whom he has been having dreams) and gets some revelations.

All the stuff that's happening brings Sophie and Lorenz closer together, and in his acceptance of the importance of ordinary love relationships and his sadness about facing his mother's decline, guess what? Lorenz turns to Mario. Sophie gets back with her estranged boyfriend. Reluctantly, but with her usual aplomb, Rosie makes a go of life at an old people's home. Lorenz and Mario move to Berlin together. Lorenz's new novel is about Rosie and the triangle he discovered when he explored his father's past.

Whether or not this film is autobiographical (and he, like Lorenz, is a Swiss gay artist long resident in Berlin) it appears more family-oriented than Marcel Gisler's previous ones. It met with a warm reception at this year's Solothurn (Swiss) Festival, where it was nominated for Best Feature Film, Best Screenplay, Best Actress, Best Actor, and twice for Best Supporting Actor. Sibylle Brunner won the Best Acress award. This film however is not a patch on Ursula Meier's exciting and original film, Sister, the Swiss Oscar entry last year, which won Best Fiction Film and Best Screenplay. But Swiss film successes on the international scene are rare, so we must welcome the engaging, thoughtful Rosie, despite its low pulse.

Rosie, 106 mins., in German, is also is included in the 2013 San Francisco International Film Festival, in connection with which it was screened for this review. It opens in the German speaking region of Switzerland in June 2013.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:35 AM.

-

Longman Leung, Sunny Luk: COLD WAR (2013)

LONGMAN LEUNG, SUNNY LUK: COLD WAR (2013)

AARON KWOK, CHARLIE YOUNG AND TONY LEUNG-KA-FAI IN COLD WAR

New directors, old theme, less success

Given California's proximity to Asia, certainly a big flashy new Hong Kong police drama is worthy of inclusion in the San Francisco film festival, especially with two new directors, Longman Leung and Sungy Luk, at the helm and som major names in the cast. But despite good scenes, mostly in the first half, this must be written off as a muddled attempt to spin a variation on the mole-in-the-force theme developed in the hugely successful Infernal Affairs (on which Scorsese's The Departed was based) and its sequels. Readers are advised to refer to Asian film reviewer Derek Elley for an expert rundown on the plot and acting highlights of this movie. I will provide a more impressionistic treatment. Suffice it to say at the outset that there are some terrific, high drama scenes here, but as Elley puts it, the film "suffers from the perennial Hong Kong problem of a weakly developed script just when things are getting interesting" -- and probably heavy editing that makes many threads get lost and some hard to follow, a flaw that was to be experienced in Infernal Affairs too. Are we not really supposed to be paying attention? The writing matters. It really does.

A lot of slickness here, with much emphasis on the high tech equipment, chiseled cool modern office interiors, chiseled-faced actors with impressive eyebrows and immaculate suits, with lots of play with focus in action scenes, cameras that like to fly down from above, sweeping symphonic background music, and an editor who knows the value of cutting from a showdown at the harbor to a beautiful babe's soft legs silhouetted in her bedroom.

The opening is provocative enough (if only it were fully developed, instead of taking a new tack in the second half). While the police commissioner is in Copenhagen at a conference touting Hong Kong as "Asia's safest city," there's apparently a diversionary operation during which a whole six-person squad of the force is kidnapped for ransom, with the cops cleverly misled into following a false trail. The deputy commissioner names himself acting commissioner and treats this as a terrorist threat to be fought by an operation dubbed "Cold War." But his aggressive manner of behaving leads to opposition on the management side and a "cold war" between operations and management. The action is a little like a Shakespeare history play. Opposing forces, particularly Tony Lau Ka-fai as the operations acting commish and Aaron Kwok as the younger management opposition, stand around glaring and addressing fiery speeches at each other.

There is suspicion that the kidnapping couldn't have happened without a cop or former cop involved -- a mole, something rotton inside, as in Infernal Affairs. The film shows great American influence in the police department, or at least a lot of American English terminology thrown about concerning procedures. Everything is staged to make an impression of top quality facilities. Gone are the dingy police station offices of yore. This film certainly celebrates the Force. However, whether all this action is meant to support or ironize the "Asia's safest city" claim remains moot. The second half's investigation by the ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption) draws a red herring across the scene. However this half has nice features, such as the young ICAC hotshot known as Billy Cheung (Aarif Rahman), an impressively cocky overreacher if there every was one. This segment is both investigative and action-centered, but it all gets a little too analytical. Gone is noir, all is corporate glass and steel, with quick gun fights and noble final declarations, and a setup for a sequel.

Richard Kuipers, who reviewed this film for Variety, overwhelmed by all the introductory material at the outset, found the first half of this film hopelessly confusing, "Bombarding auds with details and depriving them of much in the way of clarity for the first half hour,' and thought it settled down and made sense in the second part. The first half is fast-action, but it's overall structure seems clear enough, so I'd have to side with Elley's view that the real weakness comes later. Anyway, there's good stuff here, but it doesn't hang together: that much is clear.

Cold War 寒戰, 105 mins., in Cantonese, was released in Oct. and Nov. 2012 in Hong Kong and played at Taipei Golden Horse Film Festival. It was also included in the April 25-May 9, 2013 San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:36 AM.

-

Jeremy Teicher: TALL AS THE BAOBAB TREE (2013)

JEREMY TEICHER: TALL AS THE BAOBAB TREE (2012)

OUMBUL KQ IN TALL AS THE BAOBAB TREE

Tradition vs. the individual talent: arranged marriage in a Senegal village

Tall as the Baobab Tree is a striking first feature shot in Senegal by the 23-year-old American filmmaker Jeremy Teicher. The students and families of Sinthiou Mbadane, Senegal, collaborated with Teicher as cast members in making the film shot primarily in the village where they live, which he knew from previous work there.

The idea is to show the clash of generations through focusing on a high school girl attempting to resist the rather ruthless survival strategies of an African village where her father decides on an arranged marriage of an underage girl, "selling" his 11-year-old daughter Debo (Oumul Ka), the older girl's sister, to raise the money needed to pay to treat his elder son Sileye (Alpha Dia), whose leg is injured early on in a fall from a Baobab tree. Coumba (Dior Ka) vows to raise the money any way she can. She wants herself and Debo both to get an advanced education, and she gets a boy who has a crush on her to mind the cattle she's supposed to be watching as Sileya rests up, while she goes to town and works housekeeping in a small inn. It's a risky deception. Meanwhile their father (Mouhamed Diallo) looks for a man who'll take Debo as a second wife.

Coumba has trouble, constantly asking for more money and rebuffed by the inn owner. She seeks encouragement and advice from her former schoolteacher, who stands on the side of progress. With him and at the inn the spoken language is French; the rest is in the local dialect of the Pulaar language. With help from her admirer who's been watching the cattle, Coumba raises the needed money, and their father is welling to pull out of the marriage arrangement, but the village elder tells him he can't. The men are devout muslims, and their words are constantly laced with Arabic formulas expressing humility and faith in the will of Allah, and this attitude prevails, despite the counter-valance of the will of the young and the French-educated. So after a rebellious gesture, without more ado Debo goes off in a cart with her new husband.

Everything is nicely understated, with no effort at drama, the non-actors delivering their dialogue with quiet conviction, knowing very well the situations they are dramatizing. The feeling of authenticity is beautifully maintained. However, the whole thing is so low-key that only the most ethnographically inclined are likely to maintain interest to the end. However, Teicher did not act unwisely in avoiding overt violence in his story.

The outstanding feature of Tall as the Baobab Tree is the visuals and the way they capture the authentic locations and cast. Crisp digital cinematography by Chris Collins does a fine job of bringing out the beauty of the people on screen and their colorful looks and clothing and velvety dark skin. Obviously state of the art HDSLR equipment was used. Jay Wadley’s African harp score provides a delicate and natural background, aiding the rhythm and never intruding. Teicher had worked in this Sengalese village, lacking running water, electricity or other amenities, for years doing a documentary short, This Is Us (2011), previous to making this film, and has a feel and a reverence for the life that comes through here. Obviously only a well-established trust enabled Teicher to use all these villagers in roles that, in various ways, call their traditional culture into question. The issue of arranged marriages in Senegal, as he has explained in many interviews, is a big one and had come to the fore when he was making the documentary.

Tall as the Baobab Tree/Grand comme le Baobab, 82 mins., debuted at Montreal and has shown at Rotterdam and other festivals, including the April 25-May 9, 2013 San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review and where it was a nominee for the New Directors award. Also included in the June 2013 Lincoln Center Human Rights Watch Festival. Bruce Bailey's review and interview on Flickfeast from the LFF provide more information than I have here.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:36 AM.

-

Sergei Loznitsa: IN THE FOG (2012)

SERGEI LOZNITSA: IN THE FOG (2012)

SERGEI KOLESOVV, VLADIMIR SVIRSKIY, VLADISLAV ABASHIN IN IN THE FOG

Long day's journey toward moral ambiguity

Western frontiers of the USSR, 1942, the film description goes. The region is under German occupation. A man is wrongly accused of collaboration. Desperate to save his dignity, he faces impossible moral choices.

Mike D'Angelo's Cannes 2012 Tweet review: "In the Fog (Loznitsa): 50. Much more conventional than MY JOY, and somehow feels simultaneously sparse and bloated. Adaptation issue?" He means he thinks "there's an interior monologue gone missing here, as is so often the case." And indeed it often is, with loss of intellectual content over heavy mood and stark visuals. Full D'Angelo AV Club review <a href="http://www.avclub.com/articles/cannes-2012-day-nine-the-director-of-precious-drop,75685/">here.</a> People noted the director's fiction feature debut <a href="http://www.chrisknipp.com/writing/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=1588">My Joy</a> (Cannes 2010, NYFF 2010), for its formal daring with its very long POV tracking shots (admired by a cinematographer I watched it with at the NYFF), but it went haywire at the end losing narrative coherence and rubbing one's nose in increasing, pointless violence. But Variety gives In the Fog a good <a href="http://variety.com/2012/film/reviews/in-the-fog-1117947639/">review</a>, which means that it will play. And if its moral issues and plotline are all too simple, as noted by D'Angelo, therefore also people will have something easy to latch onto, which they will like. And the contemporary bleakness and absence of any musical they will admire.

When Sushenya (Vladimir Svirskiy) rescues the wounded man Burov (Vladislav Abashin) who was going to kill him for allegedly causing the hanging of the other partisans, that's where you might need interior monologue, to give Sushenya good reason for this gesture other than simply to make him seem morally superior, because it's' an unwise-seeming move, on the face of it.

As in My Joy, Loznitsa begins with a remarkable authentic-feeling crowd scene involving a long tracking shot. This is where three men get hanged and later Sushenya is released. We see the two men come to get him at home because they assume his release was due to his betraying the other men. Sushenya thinks he was released as a decoy, and repeatedly wishes he'd been hanged with the others. The purpose of the scenes that follow can only be to discuss issues of moral courage. Obviously the unhandsome, weasely Voitek (Sergei Kolesov) is despicable. His compadre Burov (Vladislav Abashin) is a well-meaning fellow, but maybe not too smart, anyway not saintly like the long-suffering Sushenya, who lasts the longest, perhaps for no reason in terms of the plot, which is gear to emphasize the pointlessness of fate.

But if this is a Beckettian journey to nowhere, as it pretty much turns out to be, one might really prefer if it were even more pointless, but more eventful. There seems to be a good deal of time spent just sitting around waiting, exhausted, wounded.

Despite its rough period atmosphere and vivid locales, its titular fog and its looming trees, In the Fog seems very talky and theatrical, one of those many films that could have been done just as well, maybe better, on the stage. Which is fine, and this is a well-crafted film that must have done something to justify its Cannes award, the opening sequence itself showing Loznitsa's ability to stage and shoot scenes in ways few can. Except that at the end I'm left agreeing with D'Angelo that there is not enough here to justify the over two-hour run-time ("The story is simple, arguably too simple").

In the Fog/В тумане, in Russian, 130 mins., debuted at Cannes May 2012, where it was awarded the FIRPRESCI Prize. A dozen festivals and releases in as many different countries followed. The last festival is San Francisco, where it was screened for this review. The film has been acquired by Strand Releasing for US distribution.

In the Fog/В тумане, in Russian, 130 mins., debuted at Cannes May 2012, where it was awarded the FIRPRESCI Prize. A dozen festivals and releases in as many different countries followed. The last festival is San Francisco, where it was screened for this review. The film has been acquired by Strand Releasing for US release (NYC) Fri., 14 June 2013.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:37 AM.

-

Mika Matilla: CHIMERAS (2013)

MIKA MATILLA: CHIMERAS (2013)

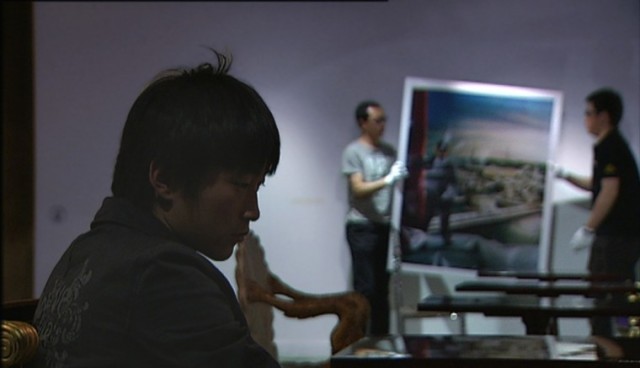

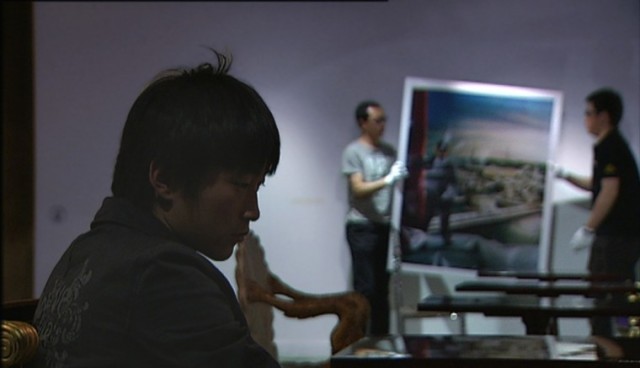

LIU GANG DURING INSTALLATION OF HIS WORK IN CHIMERAS

A complicated beast: two post-Mao contemporary Chinese artists from different generations

Wang Guangyi, puffing on big cigars, his goatee and long hair wagging, is a formidable opponent spouting angry denunciations of westernized academics in Chinese art discussions -- his clout not lessened by his being perhaps the richest artist in China. But his work, which has blended burnished Mark Kostabi-like manikin figures with Dali knockoffs and a multiplicity of images blending US pop brands with social realist poster art and revolutionary slogans (Coca Cola and Mao and "No"), important as he may be justified in saying he was as a mover and shaker of China's first wave of contemporary art, big money-maker though he is now, seems a little dated, a little Eighties, and certainly less newsworthy compared to the brave and provocative Ai Weiwei. Wang himself admits to feeling disappointed. Young Liu Gang on the other hand, cherubic and cute as a button, is still hungry, even greedy ("ten thousand is as low as I'll go"). Quietly busy and driven, clicking away with his tripod and his expensive digital camera and playing with subtle pastel images of crinkled ads ("Paper Dreams" his first big show, exhibited worldwide, was called), seems more truly contemporary and interesting. His work captures the kind of confused globalized identity mish-mash the great Jia Zhang-ke talked about in his 2004 film, The World. Liu too roams vast expensive Chinese mockups of European cultural treasures. Wang sought to fight oppressive Chinese political forces; Liu only comments obliquely on culture. Now he's wrestling, in his musings anyway, with the issues Liu depicts of Chinese East-West cultural schizophrenia.

The old and young artists' styles are very different: Wang's is declarative and coonfrontational; Liu's in contemplative and indirect. But both have the same complex: international contemporary art is a Western thing, its hunger for exotic artists a source of their success, and this has unintentionally led both of them, whether several decades ago or only recently, to see the world through Western lenses. Liu is most overtly troubled by this, because it's what he has been criticizing and delineating in his own work.

Mika Maitilla, who is Finnish but lives in Beijing, is ingenious in the way he makes the two artists strong contrasts, and at the same time a single voice of Chinese contemporary art's uneasy relationship to the West. In the end the message is rather simple and contains no revelations. But this is, already by this point, a beautiful and elegant film.

In his last third, entitled "Marriage," Matilla drifts a bit to one side. We see Liu wants to get married, but his parents object, wanting him to focus on career, all the pressure on hiim because he's of the "only child generation." Matilla keeps showing Wang pacing around impressive shows of his work, but then when Liu goes ahead and gets married, we realize we don't know a lot about the private lives of either artist. Though we repeatedly see him with his parents, Liu is private and noncommittal: how did he even meet this young woman? Wang on the other hand is very public: but has he a family or a home life? Anyway, Liu's art career seems temporarily derailed by his marriage. What a cute couple! He takes a regular job in Beijing with the Dutch cultural agency SICA, and the film ends with many handsome photos of him posing with his pretty wife. His first series exhibition was "Paper Dreams," his second "Better Life," his third, to be called "Only Child Generation," still remains uncompleted. Are Wang and Liu both chimeras, illusions, odd mixes of two unrelated beasts? Matilla's handsome film is more food for thought than an answer. With the very rich at the top of China's heap, art is a big investment game -- that aspect a topic only touched upon here.

Chimeras, 88 mins., debuted at the Toronto Hot Docs festival April 25, 2013 and was also included in the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review. Matilla is a cinematographer on documentaries who has lived in Beijing for years. He has another film in the works.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:37 AM.

-

Ilian Metev: SOFIA'S LAST AMBULANCE (2012)

ILIAN METEV: SOFIA'S LAST AMBULANCE (2012)

MILA MIKHAILOVA IN SOFIA'S LAST AMBULANCE

No prompt response in Sofia

Young Bulgarian-born, German-resident Ilian Metev, who's 22, made this film chronicling a corner of Sofia's degraded ambulance system by mounting three cameras on the dashboard of one of the city's rickety old emergency vehicles and then editing together material gathered over the course of two years. Mostly we do not get to see the victims and must rely on dialogue. A little girl is injured and the nurse, rather charmingly, asks her questions and talks and talks to keep her mind off it as they rumble over two hundred potholes on the way to the hospital. A drunk run over on the highway with a broken leg keeps trying to get up as the nurse ties on a splint and patiently orders him, over and over, to lie still till they arrive and carry him in. One place they arrive where neighrors have called he patient is not only dead, but her head half eaten away by worms. It is good we do not see. Mostly, nothing works. Yes, this is no competition for the dryly ironic nightmare of Cristi Puiu's Romanian feature, the Cannes 2005 Un Certain Regard prize winner, The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, (NYFF 2005)</a> but it makes a sort of companion piece further illustrating the nature of Eastern Block medical meltdowns. And the humanity of the endeavor and the trio of ambulance staffers is unquestionable. They come off well, given the pressures, though they show little sympathy for an aborted abortion, nor full understanding of how drug addiction works. But then, neither is really their job, which is to keep people alive on the way to the hospital, if they can get to them in time, or at all, which often they cannot. Its documentary realism will make this of interest, but for a great film, watch Dr. Lazarescu.

Are we jaded by endless American TV series about disasters and police, or films like Scorsese's dramatic Bringing Out the Dead? Or is this not the best way to compile information about what after all involves a lot of running around, when it focuses mainly on sitting in the front of an ambulance, chewing the fat, chewing gum, and smoking cigarettes? Anyway, Sofia's Last Ambulance is really about not being able to find the place, not being able to get through to headquarters, arriving too late. Other ambulances -- this isn't quite the last one -- break down. People are quitting. "There's nobody left," Krassi (Krassimir Yordanov), the male technician, says. There are two others on camera, the patient, good-natured driver, Plamen Slavkov, and the nurse practitioner, Mila Mikhailova.

There are just 13 ambulances for two million people, the film's blurb says, but we get no view of the other dozen. Poor Mila, Plamen, and Krassi seem to live in their own slow frustrating bumpy little world. Of which, due to the filmmaker's remote shooting method, we get too little a view much of the time. A health care professional reviewing the film was disappointed the injuries and treatment methods and tools were never shown.

Sofia's Last Ambulance/Poslednata lineika na Sofia, 80 mins., debuted at Cannes in 2012, where it won a new youth prize, the France 4 Prix Révélation, at Critics Week, and it has shown at easily a dozen and a half other festivals since. It is part of the documentary feature competition of the San Francisco International Film Festival, April 25-May 9, 2013, where it was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:37 AM.

-

Kiyoshi Kurosawa: PENANCE (2012)

KIYOSHI KUROSAWA: PENANCE (2012)

Guilt, murder, penance, revenge flow through four or five hours of elegant, restrained Japanese horror from Kiyoshi Kurosawa in his TV mini-series

Hollywood Reporter's overview (Deborah Young): "Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s made-for-TV serial drama Penance is a wild, uneven ride through the oddities of the Japanese psyche, as much as it is a psychological thriller examining the far-reaching aftereffects of a little girl’s murder. Complexly plotted, elegantly shot and orchestrated, this is the kind of long-winded, intermittently involving festival package that will earn the director of Tokyo Sonata more critical appreciation but will struggle to find a theatrical audience. For a film that requires nearly five hours of viewing investment, it feels terribly stingy on the emotional payoff. Divided into five interlinked chapters, it aired on Wowow television in January, shored up by an all-star cast and the morbid fascination and human interest of best-selling author Kanae Minato’s original book." Derek Elley points out that Minato's previous novel Confessions, powerfully adapted for the screen by Tetsuya Nakashima, is far darker than this, but in either case the moral complexity to which murder seems to lead in Minato's world suits well with Kurosawa's own outlook.

Four little girls see a murderer who kills their wealthy classmate Emili. Emili's mother Asako (Kyôko Koizumi, wife of the unemployed father in Tokyo Sonata) becomes the avenging angel-guilty conscience-evil presiding spirit of the piece, and she puts a spell in the girls, telling them they must do penance, whatever that means, for not identifying the killer. Asako reappears in the four stories -- 50-minute TV episodes -- that follow. I don't quite see why some think story number four, of the perky Yuka (Chizuru Ikewaki), who opens a flower shop, scoffs at Asako's threats, and indulges a penchant for policemen and adultery, provides any kind of light relief. What you realize by the time her tale is told is that all four girls have grown up to be killers, only not for revenge; it just sort of happens in the course of their differently ill-starred lives. Is Yuka more "normal" than the fragile, doll-like Sae (Yu Aoi) who marries a corporate heir even stranger than she is (Mirai Moriyama), in the first story, "French Doll"? Or than the over-strict teacher Maki (Eiko Koike), who carries martial arts a bit too far in story two, "Emergency PTA Meeting"? Or than the somehow appealing reclusive longhaired "bear" Akiko (Sakura Ando), in jail for killing her brother (Ryo Kase) in story three, "Brother and Sister Bear"? No, in her story, "Ten Months, Ten Days," Yuka turns out to be just as weird as the others and more manipulative, a home wrecker as well as a killer. The important thing is that somehow the material and Kurosawa's handling of it makes each segment feel like a piece of the picture, and yet quite unique in its own way.

Kurosawa adopts the method of staging the early childhood events in full color and the stories of present time fifteen years later in pale grays with touches of color, heightening the coolness and artificiality of it all -- in view of which the brittle, airless first tale of Sae works particularly well, serving as a good introduction for how everything is going to go (badly). As the presiding high priestess of revenge, Kyôko Koizumi, always dressed in impeccable elegance and not having aged a single minute in fifteen years, is always in control, so it's no surprise that she gets her own final episode. Though revelatory, dramatic and climactic in its own way, however, given the complexity of the whole structure this episode hardly provides a sense of full resolution.

Furthermore, though Penance is elegant and compulsively watchable, the whole setup works best if you don't think about it too much. Why should the girls do "penance" well into their twenties for not identifying a killer they didn't know? Why should each young woman seem to think her unrelated act of violence would appease the grieving mother, Asako? Well, both novelist Minae Minato and adaptor-director Kiyoshi Kurosawa understand that in the psychology of horror tidy logical connections aren't necessary -- may even work better when they're clearly askew. But the final "Atonement" section is the usual elaborate string of explanations (with more of a police procedural setup) with little real connection to all that came before. And thus the overall structure remains factitious and dubious in ways that fall well short of what one gets in great art.

Time is wasted at the outset of each 50-minute TV segment by repeating the early moments of the killing and Asako's menacing speech to the four little girls latrer. If these repetitions, needed to introduce weekly episodes, could be elided the whole would play faster and smoother in a theatrical presentation, were there to be any.

This miniseries is great fun for Kiyoshi Kurosawa admirers, not to mention its interest to fans of the wilder shores of Japanese culture. But the flaw remains that, as Deborah Young says in her Hollywood Reporter review cited above, "For a film that requires nearly five hours of viewing investment, [Penance] feels terribly stingy on the emotional payoff." This lacks the intense humanity of Mika Niskanen's 1972 miniseries Eight Deadly Shots, also included in the San Francisco 2013 film festival, or the narrative drive, charisma, and excitement of Assayas' Carlos. This was spoken of at Venice as likely to become a US theatrical release, but reviewers were dubious and the prospect now seems unlikely. What is to be hoped for is a US and UK DVD release.

In its subtitled theatrical form the miniseries (AKA Shokuzai), 270 mins., debuted at Venice in August 2012, having shown on Japanese "Wowwow" TV in January. It has also shown at Rotterdam in 2013 and in Lincoln Center's Film Comment Selects, and was part of the April 25-May 9, 2013 San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review. While Tokyo Sonata (NYFF 2008) was Kurosawa's last feature release, he has a new one, Real, debuting in May 2013 at Cannes, based on a novel by Rokurô Inui.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:38 AM.

-

SFIFF 2013 ROUNDUP (compiled for Flickfeast.uk)

SFIFF 2013 ROUNDUP

It's a bit premature to be summing up the festival. After all there are seven whole more days of films coming, counting today, Friday, May 3, 2013. But except for going to see BIG SUR at the Pacific Film Archive Sunday, I am probably done with my SFIFF film-watching. And I have watched nearly forty films. So here is a little summary along with some tentative 1-10 star ratings compiled for the website Flickfeast.uk. Those are in progress.

As usual, I have written about every film I saw. The SFIFF can be a last chance to see last year's festival films before the new ones begin, since the cycle truly starts over in mid-May with Cannes. I watched nine of the ten New Directors award nominees. Of these I particularly liked the touching little sci-fi film of Lima, Peru, after a plague, The Cleaner, but the Brazilian film, They'll Come Back, is also great and the cinematography in the Turkish film Present Tense is hauntingly beautiful.

My most memorable viewing experiences were the most lengthy ones, two made-for-TV mini-series: Mika Niskanen's 1972 Finnish saga of an alcoholic farmer, Eight Deadly Shots, starring the director, and Kiyoshi Kurosawa's intricate five-part psychological thriller of murderous women, Penance.

Of the nine films I'd already seen before I'd recommend A Hijacking, the Danish feature film about Somali pirates, a significant real phenomenon, and Sarah Polley's autobiographical Stories People Tell is a strong documentary debut for the Canadian actress-director. Also the weird, oppressive, memorably fish-eye doc, Leviathon.

In their stylish opening and closing films, Siegel and McGehee's What Maisie Knew and Richard Linklater's third in the talky Ethan Hawke-Julie Delpy romantic two-handers, Before Midnight, the festival organizers struck a very good balance of quality and audience appeal.

In my other choices I'm pleased to say that though it may not sound like it, I did well enough, so everything was decent: none that rocked my world, but no duds. I got as much variety as possible with an emphasis of fiction over documentary but with some good documentaries. So I got to range around from one language to another constantly, seeing films in Japanese, Korean, Spanish, Turkish, Farsi, Italian, French, Chinese, Finnish, Danish, and an African dialect I never previously heard of. At least a third of these may not come available on DVD, and that's the value of festivals.

I'd also single out Andrew Bujalski's uniquely nerdy 1980-set video recreation of an early Computer Chess convention. Similarly I discovered a talented super-indie American director, Mike Ott.

I hope you enjoy my reviews and through them discover some films to watch later on your own.

RATINGS:

Act of Killing, The (Joshua Oppenheimer 2012).

This is a harsh documentary about massacres in Indonesia and I did not like its tone, but it has been widely admried. Grade: 6

After Lucia/Después de Lucía (Michel Franco 2012)

A Mexican fiction film about brutal bullying at a posh high school. It has occasioned much comment, but as a treatment of the theme it is weak, and has a vague ending. Grade: 5

Artist and the Model, The (Fernando Truba 2012)

A beautiful black and white film about an aging sculptor (Jean Rochefort) who's momentarily revivified by finding a beautiful, vibrant young woman model. Nice enough but the theme is hackneyed and the action is bland. Grade: 4

Before Midnight (Richard Linklater 2013)

Julie Delpy's character has become peevish and crabby in this sequel where the couple are finally married. The romance has gone out of it but the talk is still as energetic as ever. Grade: 6.5

Chimeras (Mike Matilla 2013)

A new documentary by a Finn long resident in Beijing contrasting and linking two contemporary Chinese artists. Beautiful and elegant, if inconclusive. Grade: 6

Cleaner, The (Adrian Saba 2012)

A touching, perfectly pitched little Peruvian first film about a city employee and a little boy he rescues in the wake of a virus wiping out the male population of Lima. Grade: 8

Cold War (Longman Leung, Sunny Luk 2013)

A new Hong Kong gangster flick by two new directors with some big name stars. Very slick, but in two halves that don't fit together enough. Grade: 5.5

Computer Chess (Andrew Bujalski 2013)

Well beyond mumblecore, its godfather recreates the mood, look, and ultra-nerdiness of 1980 when computer chess was still rudamentary. This one is unique. Grade: 7.5

Ernest & Célestine Stéphane Aubier, Vincent Patar (2012)

By the guys who did A TOWN CALLED PANIC, this time adapting a popular French comics series with lovely watercolor style animation. Grade: 7.5

Eight Deadly Shots (Mikko Niskanen 1972)

Finnish 5-hour 1972 TV miniseries about an alcoholic farmer's gradual meltdown is deeply memorable and a remarkable tour de force by director-star Mika Niskanen. Should become a Criterion DVD set. Grade: 9

Fill the Void (Rana Burshtein 2012)

This was in the NYFF 2012, about an ultra-orthdox wedding in Israel. Much admired and well done (with short NYC release), but it's like an advert for a very retro style of living. Grade: 5.5

Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach 2012)

Black and white talky improv drama debuted at NYFF 2012 is like mumblecore for young white New York hipsters. Greta Gerwig is in her element but I don't think Baumbach is. Grade: 5

Futuro, Il (Alicia Scherson 2012)

I loved Chilean Scherson's debut PLAY. Here she adopts a hitherto untranslated Roberto Bolaño novel (his last) set in Italian in Rome. An oddity. It's got Rutger Hauer. Grade: 4

Habi, the Foreigner (María Florencia Álvarez 2012)

An extreme form of cultural tourism, a young woman temporarily pretends to be a Muslim in Buenos Aires to escape her drab life. Good cultural details but it doesn't quite add up. Grade: 4.5

Hijacking, A (Tobias Lindholm 2012)

Escellent, highly realistic evocation of what it's like for a Danish shipping company and a crew to be victims of Somali pirages. Grade: 7

In the Fog (Sergei Loznitsa 2012)

Much admired festival film about men in WWII Bellarus wandering through a forest mired in moral ambiguity. Metaphor over action. Grade: 5

Juvenile Offender (Kang Yi-Kwan 2012)

Well-written and acted little Korean film about a parent and child both victims of a judgmental and exclusive society. Grade: 7

Key of Life (Kenji Uchida 2012)

A gangster and a failed actor switch identities. Regarded by some as clever and witty, but this gets bogged down in detail and the pace lags. Grade: 5

La Sirga (William Vega 2012)

A young woman takes refuge in the Andes with a cousin and helps repair his crumbling shack of a tourist inn in this metaphor for Colombia's national condition. Beautiful location, draggy action. Grade: 5

Last Step, The (Ali Mosaffa 2012)

Witty and convoluted Iranian film about jaded artist intellectuals and what did and didn't go right in their lives, with the actress who starred in Farhadi's A SEPARATION. Grade: 6

Leviathon (Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Verena Peravel 2012)

NYFF 2012 Harvard ethnography doc center product fish-eye view of Mass. fishing tanker, exhausting to watch, one of their most emersive experiences and most admired efforts. Limited NYC release earlier. Grade: 8

Memories Look at Me (Song Fang 2012)

A young Chinese filmmaker goes to visit her parents and shoots herself talking to them. Much admired at fests (NYFF 2012) but I find it hopelessly drab and obvious. Grade: 4.5

Museum Hours (Jem Cohen 2012)

Cohen received the POV (Persistence of Vision) SFIFF award this year and this shows his elegance and subtle humanism as a documentary filmmaker blending a view of Vienna's Kuntshistorisches Museum with the viewpoint of a low-key couple. Grade: 6

Nights with Théodore (Sébastien Betbeder 2012)

Young Paris couple meet at a party and start spending the nights inside a park. A big creepy and not much to it. Original premise, though. Grade: 4

Night Across the Street (Raul Ruiz 2012)

Too complicated to explain here but this acts as a kind of summing up of the late master's themes. Grade: 8

Patience Stone, The (Atiq Rahimi 2012)

A very handsome but overly symbolic and theatrical film based on the director's own novel about an Afghan couple trapped in the war in Kabul. US release. Grade: 6

Pearblossom Highway (Mike Ott 2012)

A young ultra-indie US director worth knowing about, he focuses on marginal young people in a nowhere SoCal town. His previous LITTLEROCK you can watch on Netflix instand play. Grade: 6.5

Penance (Kiyoahi Kurosawa 2012)

In between TOKYO SONATA and the new REAL Kurosawa made this elegant 4-5-hour TV miniseries about murderous women based on the novel by Kanae Minato. This is going the rounds and was in Film Comment Selects. Grade: 8

Present Tense (Belmin Söylemez 2012)

A divorcee getting by barely in Istanbul as a fortune teller. Captures marginal survival strategies well and has lovely cinematography. Grad: 7

Rosie (Marcel Gisler 2013)

Little film about a gay writer who returns from Berlin to deal with his alcoholic, ailing mom. Sibylle Brunner won Best Actress at the Swiss awards. Grade: 5.5

Sofia's Last Ambulance (Ilian Metev 2012)

Three HD cameras stapled onto the dahsboard made a chronicle of exhaustion over a two-year period, but a fuller documentary of Bulgarian emergency services to have gone out with the crew more, wielding a handheld camera, and showing more of the actual treatments and patients. Grade: 5

Something in the Air (Olivier Assayas 2012)

Assayas, attractive, but shapeless autobiographical feature about kids chasing the revolution that vanished after May '68. Grade: 6

Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley 2012)

(New Directors 2013 entry). Polley's strong doc debut is about her own life and investigates her confused patrimony. Grade: 7

Strange Little Cat, The (Ramon Zürcher 2013)

German first film is more a logicstical game than a film but very clever and precise as a Swiss watch. Grade: 5.5.

Tall as the Baobab Tree (Jeremy Teicher 2012)

A young American's gorgeously shot drama about teenage girls in revolt in a village in Senegal profits from his excellent rapport with all the people. Ultra low-key action though. Grade: 6

Thérèse Desqueyroux (Claude Miller 2012)

Claude Miller's last film is the Mauriac novel redone with less verve than Georges Franju's 1952 version and Audrey Tautou instead of Emanuelle Riva. Grade: 6

What Maisie Knew (David Siegel, Scott McGehee 20113)

Typically cold-blooded and unfun, this Siegel-McGehee remake of the Henry James novel fits its plot neatly into cotempo Manhattan. Their best since THE DEEP END. SFIFF opening night film. Grade: 7

Youth (Justine Malle 2013)

Alas, daughter Justine Malle's fictionarlized study of her celebrated New Wave director father's last days and what she was doing at the time seems too little, too late and in the protag role Esther Garrel hasn't at all her brother Louis's charisma or sex appeal. Grade: 4.5

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:41 AM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks