-

Raul Ruíz: NIGHT ACROSS THE STREET (2012)

RAUL RUÍZ: NIGHT ACROSS THE STREET (2012)

SANTIAGO FIGUEROA AND SERGIO SCHMIED IN NIGHT ACROSS THE STREET

A summation with a light touch

Raúl Ruiz is the Chilean auteur known for Time Regained (a symphonic riff on Proust) and his lush recent miniseries Mysteries of Lisbon (but director of more than 100 films if we include shorts and documentaries). Though he lived in exile ever since the dictator Pinochet came into power in 1973, he was reportedly greeted affectionately on the street in Chile as "Don Raulito." He died in France last year, shortly after his seventieth birthday, after a serious illness that had been temporarily reversed by a liber transplant, and after a celebrity funeral in Paris his body was returned home and a day of national mourning was declared. La noce de enfrente/Le nuit d'en face/Night Across the Street is an intentionally posthumous cinematic last testament. Ruiz told the younger crew members on the rapid shoot that it was his last film, but concealed this from friends and family and producer (and friend) François Margolin. The title could be translated as "the coming night" -- as it is at a key point in the film's English subtitles -- and thus mean the oncoming darkness, the approach of death. Conversely it's already being celebrated for its youthfulness, for being more like a first film than a final one. Indeed it is a lighthearted, amusing, playful and surreal film that slides around in time with a freedom that may baffle the first-timer. For that matter it may not be too clear on the fifth or sixth viewing -- if you haven't done your homework in between. This is a film for Ruiz aficionados and selected festival-goers.

But it's not like the film itself is a total, baffling mystery. Ruiz himself provides an excellent Night Across the Street for Dummies in the form of a brief Cannes Statement about the film. His starting point, he explains, is the Chilean writer Hernán del Solar (1900-1985), one of a group of Imagists who went against the naturalism that grew up in the Forties and Fifties. "In Del Solar's works," Ruiz writes, "daily life coexists with the dream world, with tenderness and cruelty, the literary evocations and the omnipresence of the universe of childhood." That tells you also what to expect in his film. Two of Del Solar's stories, Ruiz also tells us, are "Wooden Leg" and "The Night Across the Street." "Wooden Leg" is derived from Long John Silver of R.L. Stevenson's Treasure Island, of which Ruiz, whose father was a ship captain and who had a lifelong fascination with pirates, had done a screen adaptation. He's a character in the film, this Wooden Leg (Pedro Villagra) , and so is Beethoven (Sergio Schmied), or a Chilean child's imagined version of the German composer.

The film begins with an engaging scene of one Don Celso (Sergio Hernandez) sitting in a class taught by the writer Jean Giono (Christian Vadim), a provincial Frenchman whose daughter Ruiz, he tells us in his statement, once met. She told him how Giono, who feared even going to Paris, once announced to his family that he was going to move to Antofagasta, a port in the north of Chile, which he picked solely because he liked the name. In the film he is there, teching a class in French literature in which he asks students to close their eyes and meditate on his words.

The story of the film, Ruiz tells us in his statement, takes place in Antofagista in the present time, and there are modern buildings, as well as ones from the past; but the characters don't see the modern ones. The film, we could say, creates a limbo between past and present, real and fantasy, and lingers there, ready to shift back and forth at a moments notice.

Starting with the poetic classroom of Jean Giono, the film plays with various verbal motifs, particularly recurring to the word "rhododendron." The little boy in the story, the young Celso (Santiago Figueroa), is sometimes known as "Rodo." The old Don Celso works in an office and is about to retire; but the film often shows him in his imaginative boyhood, when he has conversations with Beethoven and Wooden Leg. Following what he considers an Imagist stye worthy of Hernán del Solar, Ruiz imagines the mature Don Celso likewise having conversations with Jean Giono, even though Giono is also a writer working in France. And Don Celso is also in a rooming house, where he expects someone is going to come and kill him. As Ruiz puts it, "the horror of an impending crime grows in importance." He also says this is "a weaving narrative, only half explicit, and a dark story of crime and treason."

This threatening plot element serves as a thread pointing toward a definite finale (the "coming night") and thus offsets the playful shifting back and forth between present and past, reality and fantasy, of the film's minute-to-minute texture. It's a Whodunit! Or almost. Several pistols are introduced, and they have to be used, except that we don't ever literally see them used; we only view corpses, and figures with red bullet wounds, who are alive. In the context of this film "Imagist" evidently means "surreal," and the mindset of Ruiz's film is certainly more surrealist than super realist. The ghost of Jorge Luis Borges (perhaps due to the affection for Stevenson) seems to hover somewhere, even though Borges was from Argentina and not Chile. Borges' dates are very close to Del Solars, 1899-1986.

Ruiz ends his film statement with a funny mistake -- confusing two utterly different modern artists. The "possible world" of Giono in Antofagasta that threads through Night Across the Street contrasts with the "real" world of the modern town that the characters "ignore and refuse." He says this is like the painting "of Matisse" that shows a pipe with underneath it the legent, "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" ("This is not a pipe"). He meant Magritte, of course. But who knows: perhaps in this kind of auteurist cinematic world, "Ceci N'Est Pas Une Pipe" was painted by Matisse!

Justin Chang's Cannes review for Variety has a fine description of the film's modality. Mentioning the director's "smoothly panning camera movements and ingenious sense of staging" he goes on to say, "Ruiz has a way of positioning the protagonist both within and outside his own recollections, as though observing and participating at the same time. The director's frequent use of doorways and mirrors to frame and isolate his characters suggests many layers of (un)reality nestled within this curious dreamscape, whose transparent artifice is underscored by the film's intense level of stylization, especially apparent in the gold-burnished tones of d.p. Inti Briones' HD lensing." Prepare not only for a head trip but a sweet and dreamy visual experience, which may remind you of recent films by the now 103-year-old Manoel de Oliveira.

Night Across the Street is the quintessential justifiable festival film, much more so than the mainstream release titles, Story of Pi, Flight, and Hyde Park on Hudson, shamelessly included in the Main Slate of this supposedly "elite" and "highly selective" festival to sell tickets, not to mention arty but drab and uninspired titles like Memories Look at Me, Araf, or Here and There.. Richard Peña, the director of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, has said that the New York Film Festival has chosen Ruiz films to be in the elite selection of its Main Slate, but never just any Ruiz film. This is hardly any Ruiz film, because though it may be hermetic and obscure it is also beautiful -- its delicate images in a lovely haze created by the yellow filter -- and as the final work of the great exiled Latin American auteur, it deserves a very special place. I didn't really very much enjoy watching it but I enjoy thinking about it, and I would probably enjoy watching it again.

La noche de enfrente debuted in Cannes' Director's Fortnight in May and has continued to a number of festivals including Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver and New York. Watched at the NYFF press screenings for this review. It also opened in Paris in July receiving critical raves (Allocné 4.1).

FRENCH FILM POSTER

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-28-2012 at 08:29 PM.

-

Ang Lee: LIFE OF PI (2012)

ANG LEE: LIFE OF PI (2012)

SURAJ SHARMA IN LIFE OF PI

Ang Lee films an unfilmable book, and does a pretty bang-up job of it

Ang Lee's film adaptation of Yann Martel's 2001 Booker-Prize-winning sea adventure of an Indian boy and a Bengal tiger is a winning combination of the narrative and the visual. Thanks to Suraj Sharma, the young actor who plays the oddly named Pi during the key period of his 227-day ordeal in a lifeboat, and to state-of-the-art CGI that makes a hyena, a zebra, a baboon and the tiger come to vivid life in 3D as they duke it out in the confines of the boat, this Life of Pi is a stunning experience. If it has shortcomings, they are those of the book. Despite the terror and the beauty, not to mention the considerable wit and invention, something is emotionally lacking. An initial description of the father's zoo in French Ponticherry, India and the boy's swimming lessons and spiritual explorations -- he is a hindu, but also joins the Catholic church and becomes a practicing Muslim -- sets things up and conceivably makes the long Jobian torment on the water seem like a testing of the soul. But that's an idea, not a passion or a spiritual truth. This inner shortcoming may not matter to many in the audience, because as in Crouching Tiger (this tiger does a lot more than crouch), Ang Lee provides stunning eye candy and lots of excitement too. Do we ever think Pi isn't going to make it? I don't think so. But Sharma, who carries off his long period on screen with flying colors, is being spoken of for an Oscar nomination. Dev Patel has a rival, one with more soul and warmth if less of a comedic edge, and a similar sports and martial arts background.

What is Life of Pi ultimately about? The frame story in which the mature Pi relates his experience to a writer in Canada seeking material (Rafe Spall is the writer, Irfan Khan the older Pi) tells us that he now teaches religion and philosophy. The focus returns to him when he describes how Richard Parker (the Bengal tiger's name), once they finally reach land on the coast of Mexico, simply walks off along the beach and disappears into the woods. Pi desperately wanted some closure, after that long time together. When he recounts this meaningless parting he weeps. He began terrified of Richard Parker, then managed, if not to tame, at least to train, him, so he didn't get killed, and finally, exhausted and starving together, they almost became loving companions.

I think the tiger is Pi's key to survival. Maybe the struggle with the tiger kept the struggle with hunger and the elements from being overwhelming. Ultimately Richard Parker was company: strange company, but he kept Pi from being alone. Or maybe Pi is the tiger, or the tiger is the inner demon in himself that Pi must tame (or train). There are hints -- stronger in the film than in the book, I think -- that all this may be invention. And then the animals in the boat may have an allegorical meaning, while the story becomes a study in the meaning of narrative itself. But this may be asking a bit much of a film that's so pretty and ultimately so light, adapted from a book that is so focused on physical events.

It's a good story. It's an old-fashioned story. In a way it's like Robinson Crusoe -- only without the island and without Friday, which takes away a lot, but adds novel creatures as well as natural phenomena which the film also stunningly recreates. Ang Lee's movie is a pleasure. But ultimately I'm not sure that it matters. However, though you never know how it will turn out when the selection is first made, it seems like a good choice for the New York Fim Festival's opening night premiere film, which it is -- well calculated to appeal to patrons who are not film buffs but might respond to an original tale beautifully told.

On the other hand, like Flight and Hyde Park on Hudson, two other selections, Life of Pi doesn't seem like the kind of film you need to include in an "elite" and "highly selective" event like the New York Film Festival, (whose Main Slate is honed down to only 33 films). But economic and box office reality mean that you need something that won't put off those patrons, and you need to sell tickets. Life of Pi is likely to sell plenty of tickets when it's released, as well.

The cinematography is pretty, but the music by Mychael Danna; is conventional. The screen adaptation by David Magee (of Finding Neverland) captures a lot of the book, but minus the grittier and more harrowing or grotesque details that would take us as deep into the ordeal as Martel does. Rafe Spall is probably a less interesting presence than Tobey McGuire, who was originally going to be the writer. For that matter Irfan Khan is not as winning as his younger avatars, and the narrative sessions between Khan and Spall are somewhat clunky and obtrusive. Ayush Tandon, on the other hand, is very appealing as the young Pi who first takes on the world's major religions. Gérard Depardieu seems wasted as the oily and repugnant ship's cook: one can't help feeling some of his footage wound up on the cutting room floor.

But to compensate for any shortcomings in detail or superficiality in the story, Lee provides virtuoso displays of old-fashioned cinematic skill embellished with state-of-the-art techniques, the CGI augmented by the use of the world's largest self-generating wave tank, where the smoothly circling camera builds astounding images of the shipwreck and the lifeboat at sea, with Sharma going through heroic and convcincing changes of weight and appearance and emotion in the course of Pi's shattering but triumphant ordeal.

Life of Pi, 127 mins., debuted at the NYFF. Screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, in which as mentioned it was the opening night film, and premiered, on September 28, 2012. It shows at Mill Valley Oct. 14. The US theatrical release date (Fox) is Nov. 21; the French one (as L'Odyssée de Pi) Dec. 19; and in the UK, the day is Dec. 21.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-17-2016 at 01:06 AM.

-

Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Véréna Paravel: LEVIATHAN (2012)

LUCIEN CASTAING-TAYLOR, VÉRÉNA PARAVEL: LEVIATHAN (2012)

Into the net

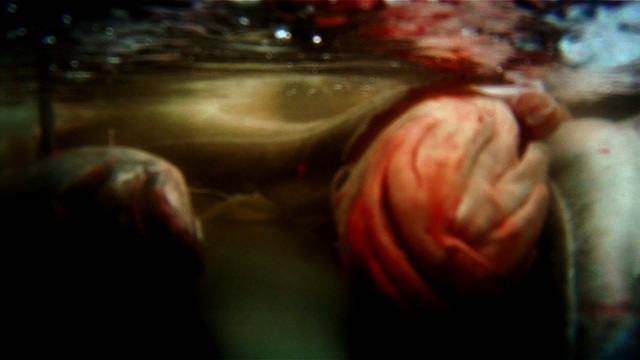

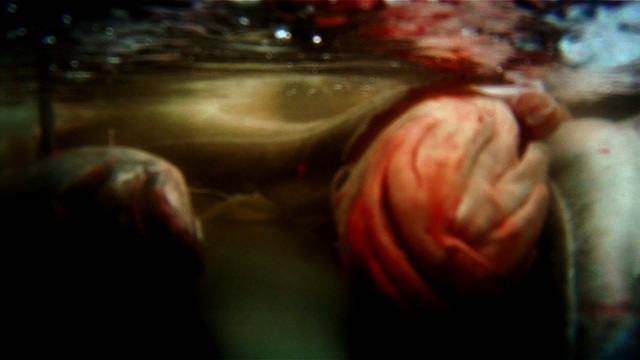

From a Locarno debut, this grueling but beautiful documentary film by Lucien Castaing-Taylor (Sweetgass) about fishing on a big vessel with giant nets. The filmmakers had lost all their equipment and went back with tiny non-pro waterproof digital cameras and used them for fly-on-the-wall (or on the wave) shots that sometimes give the fish-eye view. Oppressive loud noise from engines and machines (and weather and water) both overwhelm and calm, as violence in Hollywood movies, now so familiar, can sometimes put one to sleep. There is a sense of a vast process going on over which nobody has very much control. Who are the fishermen and who or what is being caught? The small cameras produce raw, sometimes slightly fuzzy images and when the colors of the fish go garish -- ther is a lot of glossy white and a lot of red -- the paintings of Chaim Soutine and Oskar Kokoschka come to mind. iIt's that kind of lush beauty-in-ugliness photography. Seeing the film at Toronto, Mike D'Angelo in one of his puzzlingly-precise instant Twitter reviews gave it a (for him) very high score of 73, and commented only: "Still wish human beings were kept strictly on the periphery. Purely abstract imagery astounding." This is true, but he might consider that we as viewers are in fact "kept strictly on the periphery." It's just like watching as a child taken aboard for the day and not allowed to do or understand anything. No explanations. And no likelihood of mainstream interest. Another utterly justifiable festival film choice and one that keeps the New York Film Festival honest, eclectic, and still edgy and fresh. But there is not much to say because the honest reaction is to be left speechless.

If you do go on to question and discuss, up comes the issue of the politics of such a film. Are the fishermen and the industry being unjudgmentally embraced, or brutally caricatured? Or do the filmmakers really know? As the Variety review points out, in the first twenty-five minutes it's very hard even for the viewer to know what he or she is looking at. It's just confusing, loud, elemental, and scary, and that's surely intentional. This could be the novice or visitor's initial bafflement, or it could be the captured fish's helplessness. We as viewers are rendered as passive as the catch. The fishing trawler near New Bedford, Massachusetts is going to be followed "without any context or commentary." But it is not going to be made pretty (except for a few shots of seagulls flying across a pale sky, which it seems many have chosen, misleadingly, as an emblematic images of the film).

The cameras are used roughly, strapped to the fishermen's arms, set on a floor jammed with dying fish, floating on or stuck under water. And fish are gathered and sloshed around en masse, confusingly. It is often hard to recognize that they even are fish or what fish or what parts of them are in view. In a way this is a film about the gathering and preparing of food for humans. That's what's essentially going on. One thinks of another New York Film Festival film from 2005, Nikoilaus Geyrhalter's Our Daily Bread (NYFF 2006). That documentary too is wordless, with no explanation, except for some data at the end. But it's a comprehensive survey of various food factories in Germany, coldly, cleanly, and elegantly filmed. It's an alienating film, with a kind of smugness about it. Leviathon is the opposite in every way. It might make people angry too, but for sure it's not smug. There's a kind of mute passion in it.

But the British-born Castaing-Taylor, a Harvard ethnographer and filmmaker, may simply be trying to reflect the messiness of life. That's what he told the New York Times in an August 2012 interview: “If life is messy and unpredictable, and documentary is a reflection of life, should it not be digressive and open-ended too?” Castaing-Taylor's e Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard was responsible for both Sweetgrass (NYFF 2009) and the new film. Sweetgrass, with its vast open landscapes and grazing sheep and long silences, provides an utter contrast to the clangorous, wet, noisy, in-your-face Leviathon. And as Sweetgrass benefitted from special long-distance remote sound recording, Leviathon profits from its tiny portable waterproof cameras that seem able to wedge their way into anything. Castaing-Taylor and his partners are committed to tempering intense ethnographic research with post-shoot aesthetic reconsiderations. He eschews the information-heavy, didactic bent of most documentaries in favor of something completely different. And we do get tired sometimes of films that read like Power Point lectures. Much as we like being provided with memorizable and digestible information, the world is a very indigestible and confusing place, and enlightenment may best begin from the kind of sensory overload and challenging cinematic experience Leviathon provides.

Castaing-Taylor's collaborator this time, Véréna Paravel, worked with J. P. Sniadecki on the Iron Triangle doceuentary, Foreign Parts, shown as a Special Event in the 2010 New York Film Festival (I watched it with pleasure but did not review it).

As mentioned Leviathan debuted at Locarno and was shown at Toronto. Screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, September 2012. It was shown right after Life of Pi at the press and industry screenings. One was a little waterlogged by the time they were over.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-14-2015 at 04:37 PM.

-

Miguel Gomes: TABU (2012)

MIGUEL GOMES: TABU (2012)

CARLOTO COTTA AND ANA MOREIRA IN TABU

a

Shooting back in time to an exotic forbidden love

The title the director Migues Gomes has given his third feature, Tabu, alludes to a fictitious mountain in an undesignated Portuguese African colony in the 1960's. It's also an allusion to F.W. Murnau's 1931 movie, Tabu: A Story of the South Seas . The second half of the new film, shot in 16mm. black and white film and converted to 35mm. in old fashioned square format (as is the lackluster first half) tells a story of doomed but passionate adulterous love between a dashing, mustachioed musician, Gian Luca Ventura (Carloto Cotta) and Aurora (Ana Moreira), the young wife of an equally young but less exotic tea plantation owner (Ivo Müller). The story like a Somerset Maugham short story without the punch line, or Hemingway one without the moral complexity. It's a bit shallow; but it's nonetheless beautiful, stylish, and inventive. Gomes' first half, centered on the adulterous lady as a tiresome senior citizen in Lisbon (Laura Soveral) who loses everything at a casino and then dies in hospital, is heavily scripted and featuring several drab, uninteresting older women. It's only when the former love, Ventura (Henrique Espírito Santo), still distinguished looking, appears after the funeral and begins telling the story that the good stuff begins. You could certainly argue that the first part is necessary to set up the long voiceover and semi-silent dumbshow of the adultery tale, but it doesn't need to be so long. One brief description in the Village Voice by Nick Pinnkerton calls this "a broke-back, diptych film," noticing that Murnau's Tabu is similarly split. As Pinkerton's word, "broke-back," suggests, there's something uneven and disabled about this film's construction.

When the filmmakers got to Mozambique they threw away the strict playbook they used for the first part and instead improvised their story's details from day to day. They got the cast to pretend to talk, but as we watch their many activities, including music by a depressing pool and a brief scene of surprisingly sexy lovemaking (given the period formality of much of the rest), we only hear the voiceover, and ambient sounds of nature, suggesting the place is still alive but the people are long gone; also alluding to silent film, though the date of the events is during the time of rock and roll, and the musician-lover is drummer in a band that plays and sings in English in an American rock-pop style. Gomes really does achieve a sense of time-travel with this mood and format.

While Gomes' film is flawed, it is evocative and very cinematic; even the name Aurora is a reference to Murnau's 1931 film, though in a Q&A after the NYFF press screening, the Portuguese director made clear that his memories and allusions to earlier films are vague and impressionistic -- and that the film isn't meant to be a comment on the Portuguese colonies that were freed in 1974 but rather a comment on movies (and stories?) about adulterous love affairs in this kind of setting. Ventura becomes guilty about the forbidden relationship and tries to end it. But many decades later the two lovers still pined for each other; Aurura's husband had died young but she had never remarried.

The music has an excellent period flavor. Gomes' dp Rui Pocas shot the Lisbon contemporary scenes in 35mm, the flashback ones in 16mm, contrasting a crisp look with a blurrier more vivid one. With his tan, sinewy slimness, and little mustache Carloto Cotta, as the young lover, has a deliciously seedy-sexy quality and the Variety reviewer Jay Weissberg, who saw the film at Berlin, is right to mention also that "he has the suave, captivating elegance of a young Errol Flynn." Cotta gives the doomed romance sequences their signature look. A part of the visual theme too is the cunningly old-fashioned way the starkly mountainous landscapes are shot, and the motival use of a small crocodile that Aurora's husband gives her as an eccentric present, but later disappears and winds up at Ventura's place -- twice.

Flawed, slim, Tabu is nonetheless memorable and a good choice for a film festival, but is also getting world releases. It's distributed in he US by the new label Adopt films (Jeff Lipsky), as is another NYFF Main Slate item, Christian Petzold's excellent Barbara. It debuted at Berlin and has shown at other international festivals, and will be released in the UK Sept. 7, in France Dec. 5 and the USA (NYC) Dec. 26, 2012. Watched for this review as part of the press & industry screenings of the 50th New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, Sept.-Oct. 2012.

Tabu begins a limited US release Dec. 26, 2012 at Film Forum, NYC.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-16-2015 at 07:52 PM.

-

Marc-Henri Wajnberg : KINSHASA KIDS (2012)

MARC-HENRI WAJNBERG: KINSHASA KIDS (2012)

Runaway child "witches" join a band

Kinshasa Kids is at least an admirable idea: to make a mixed-genre movie using the street kids of Congo's semi-wrecked capital. There are twenty-five or thirty thousand of them, mostly branded as "witches" by father's whose wives have left them or by second wives who don't want to raise somebody else's child. They are sent to churches for expensive (and terrifying) purification rituals (shown at the film's outset), but those don't keep the kids from being rejected and so they run away to live by stealing (the film follows one). The Belgian director Marc-Henri Wajnberg decided to make a sort of musical. Or at least the little group he narrowed down to his core cast of eight kids he groomed as a band. He found a local rapper called Bebson Elemba, dubbed in the movie "Bebson de la Rue" -- the local patois has a liberal mix of French in it and some of the street people -- a prostitute, for example -- can speak an approximate form of the Gallic tongue. Bebeon becomes the group's leader.

When Jose, the kid we follow from home to the streets and rooftops of Kinshasa, joins a group with one boy who befriends him, he's asked to sing, to justify inclusion among them. Bebson takes the boys and the one girl to a makeshift studio and "auditions" them and sees their potential marketability. His own as yet unrealized hope to make a CD is alluded to amid the rapid and chaotic dialogue that accompanies the camera's sweeps through the streets.

The result is colorful, alright. The Congolese and these kids in particular are warm and funny and full of life. But as filmmaking, despite nimble camerawork by Danny Elsen and Colin Houben that even follows a fast foot chase through the rubbish-strewn streets, is mediocre. This partly due to the editing: Wajnberg appears to have had too much footage to deal with. It's also due to his peculiar notion that documentary style is scarmbled and only semi-coherent as narrative. It seems Wajnberg is trying to do something like Marcel Camus' classic Black Orpheus -- without the mythological theme or the charismatic stars or the inspired filmmaking. But he can't bring out his gang of eight clearly enough from the surrounding crowds. There is a lot or funning around, squabbling, and chatter, and while the film uses fake cops to dramatize the constant demands for bribes (justified by the fact that the police had not been paid for many months), there's also a real car crash and real cops who rush in afterwards. There's all this stuff happening, and the kids' story half drowns.

You get a view of insanely overloaded train cars, people hanging out of every wondow and standing all over the roof; and insanely overloaded motorcycles. There's some snappy, hard-driving music from the little band; there's also a classical concert with orchestra and chorus performing Mozart's Sanctus that is supposed to inspire the kids to collaborate with Bebson in a public concert using borrowed or stolen audio equipment. Wajberg and his collaborators don't know how to get close enough to the individual kids for personalities to emerge, except one, Rachel, is a girl, and another, Mickael, who wears a tilted bowler and does a passable Moonwalk, aspires to be like Michael Jackson. Bebson wears these weird sunglasses. Wajnberg may have had a bang-up time, and his instant kid stars may have been lifted from Third World poverty and homelessness, but his flashy postcard falls flat. Wajnberg has made pure documentaries up to this. He doesn't seem to have quite understood how to morph his methods into a fictional story. A Screen Daily review from the Venice screening suggests this film "is most obviously a feel-good story in the long-running ‘society outcasts form a band and achieve success’ genre – and it’s here that it doesn’t quite deliver," for the reason that the trajectory is not convincingly followed. All the local color gets in the way. Fiction means telling a satisfying story, and for all its vivid material, that goal eludes Kinshasa Kids.

There is a throwaway appearance by Congalese musical superstar Papa Wemba. The core street kid group: Jose Mawanda, Rachel Mwanza, Emmanuel Fakoko, Gabi Bolenge, Gauthier Kiloko, Joel Eziegue, Mickael Fataki, Samy Molebe , plus Bebson De la Rue.

Kinshasa Kids debuted at Venice and also played at Toronto. Screened for this review as part of the Main Slate of the 50th New York Film Festival, at Lincoln Center, October 1, 2012.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-01-2012 at 09:55 PM.

-

Alain Berliner: FIRST COUSIN ONCE REMOVED (2012)

ALAN BERLINER: FIRST COUSIN ONCE REMOVED (2012)

EDWIN HONIG IN FIRST COUSIN ONCE REMOVED

"The mind can be blank and still be going: that's the trouble"

The ravages of Alzheimer's on a distinguished mind is the subject of this beautifully edited, well (if far from fully) contextualized study of Alan Berliner's cousin, the poet, translator, and professor Edwin Honig, who died last year at 91 with Alzheimer's disease. The film focuses on material gathered on regular visits over a five-year period and the steady deterioration of memory from confusion about who Berliner is to being unable to recall simple words and sequences of words, but with a great many variations in between, both awesome and troubling. At the end Honig is often making noises rather than talking. But all along Berliner stimulates him with photographs, memorabilia, and questions, and even in ruins this intellect is fascinating and remarkably poetic, at worst Lear and the Fool combined. He can suddenly utter a line of poetry or a keen observation about his situation. "Time now is what I do when I sit in this chair," he says. And he utters paradoxes like "Try to remember how to lose memory." Cuts from interviews with relatives, former students, and close friends fill in details about Honig in the role of father, teacher, and friend. The testimony of two sons and an ex-wife particularly underline that he could be a cruel and difficult man. He can't attach any meaning to the word love. This HBO documentary can be disturbing, especially to those in fear of what old age may bring (this didn't happen to Honig full-on till his mid-eighties). But in making the film, as Honig once suggests, Berliner is making a "poem," one that perceptively dissects and embodies themes like time, memory, and achievement.

The hard-heartedness of the man has its clear origins in an unloving mother and father. Honig's father was a cantor with an exalted sense of his own godliness and a low opinion of his son. As a boy of five, Honig ran out in the street and was followed by his three-year-old brother, and the brother was run over and killed. The father, devastated by grief, took refuge in forever blaming the boy. This terrible accident is the one thing from his life, Honig says, when asked, that he can't forget. The many books he published, the universities where he taught, the children and wives, the high honors bestowed by the Spanish and Portuguese governments for the translations of great literary classics of both countries -- all forgotten, or recalled only when his memory is jogged by Berliner. But not that terrible dash into the street and the cab that ran over his littler brother, or, no doubt, the cruel burden of blame bestowed by his father. That too he can recall.

In 2010, Berliner edited some footage he'd shot of Edwin Honig called “56 Ways of Saying 'I Don’t Remember'” and “Time and Again” (a title borrowed from an anthology of Edwin’s poems). Both of these were included in a more limited earlier recension called Translating Edwin Honig: A Poet's Alzheimer's (2010) that was shown as a a sidebar item of the 2010 New York Film Festival.* In the 2012 edits, Honig developed a use of repetition and quick cuts to give a layered sense of Honig's rapidly deteriorating memory and changed look and personality. In addition to adding the interviews for this new longer film, which considerably expands the sense of context, Berliner has also unified the film and given it a metaphorical context by using typewriter clack-sounds accompanying quick cuts. Thus sequences are pulled together and allusion is made to the quick mind, sudden revelations prompted by Berliner, or mental gaps. These effects blend with shots of the manual Hermes typewriter on which Honig did most of his writing as well as even more metaphorical images of a blackbird tapping on the keyboard with its beak -- suggesting one knows not what, perhaps the cruelty of Honig's pen or his brutal honesty.

A revelatory gesture on Berliner's part was his effort to interview the two young (adopted) sons of Honig's young second wife, who had been estranged from their father since childhood. He went to California to film the blond younger son who declined to revisit his declining father and who says that it's over now, that he forgives the man, but his only "problem" was that he was "an asshole." It rings true, and this must be balanced against others' testimony of love and admiration for Honig -- but understood in the context of early traumas that, the film suggests, Honig never managed to dealt with. A sweet touch is footage of Berliner's own very young son playing with the old man, whose love of music is fed by their sharing time on a wind instrument and a piano. These visits by the boy, non-judgmental, wholly in the present, show the ravaged Honig smiling and happy, even willing to say "I like you." But it is chilling to hear the words of Honig's former young wife, originally his very pretty student, who raised those two boys alone after Honig was asked to leave. She says that one lasting effect of her time with him is that she has never been able to read poetry since.

Since Berliner has included so much more about relationships in this fuller film sponsored by HBO on the basis of the earlier one, it's a shame he doesn't take more of a stab at explaining the disconnect between the love and admiration of some and the negative picture of Honig as husband and father. But the footage of Honig with Alzheimer's is perhaps still too much a main focus in this version to allow space for further analysis of the man, and much about his life goes unmentioned. Nor is this meant to be a full biography of someone who had a very rich working life.

Earlier films by Alan Berliner include Intimate Stranger (1991), a study of the double life of his maternal grandfather, an Egyptian Jew who went to live in Japan as a cotton merchant, and Nobody's Business (1996), an intimate study of his own father, Oscar Berliner. Berliner's exhaustive but also witty examination of his chronic insomnia, Wide Awake, was included in the 2006 San Francisco International Film Festival. This documentary, which will be shown on HBO, is part of the main slate of the 50th New York Film Festival at Lincoln Centeer, where it was screened for this review, and debuts there. In a Q&A Berliner said he had barely findished his editing, and might still be too close to the material to know fully how he feels about it and about his complex cousin.

__________________

*I saw this earlier version but did not write about it.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-01-2013 at 08:55 PM.

-

Rama Burshtein: FILL THE VOID (2012)

RAMA BURSHTEIN: FILL THE VOID (2012)

YIFTACH KLEIN AND HADAS HARON IN FILL THE VOID

Jane Austen with Rabbis

An 18-year-old girl in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Israel wavers about marrying a man when her sister dies and leaves him a widower in this film made in part for television. This will be an intensive introduction to its unusual community for some viewers; at the same time, the claustrophobic, slightly romanticized and simplified account, shot with closeups and soft focus, goes into little depth except about its one topic. There's none of the boldness and excitement of Haim Tabakman's 2009 Eyes Wide Open, a powerful movie set in Jerusalem about a married ultra-Orthodox butcher who falls in love with a handsome young man -- or Holy Rollers (2010) a film based on fact in which Jesse Eisenberg plays a New York ultra-Orthodox Jewish youth who becomes a drug mule. Fill the Void feels like a publicity film for Jewish Orthodoxy, if an odd one. Along with the soft focus, and the handsome lead couple, there is pretty music, notably a sweet choral setting for the lines beginning "If I forget you, O Jerusalem," which is played no less than three times.

A whole lot of davening -- the Jewish swaying to accompany relligious recitation -- goes on in Fill the Void. Women daven when just sitting taling. Shira (Hadas Yaron), the eventual bride, davens even when she sits in her white gown waiting to be married. Before the davening, Shira does a lot of wavering. Unlike the heroine of a Jane Austen novel, which arguably considers the same series of false starts and reconsiderations before a young woman joins with a young man, this movie has a very slow intensity, but lacks subtlety or complexity, as well as a larger social context of status or work. These people appear prosperous, to judge by their clothes and their well-appointed kitchens and the prospective groom's nice Volvo. What doee he do? As we see them, these are people who only marry, have babies, and meet with their religious leaders. In the end, it becomes clear that people of the Haredim or ultra-Orthodox community lives in a less advanced and democratic world than that of Jane Aussten's Hampshire in the early nineteenth century. And yet according to Jay Weissberg's Variety review written at Venice, Austen is Burstein's "stated influence."

But if Fill the Void is essentially shallow, and its simplicities and shallow focus imagery mark it as best suitefd for TV, even as a promotional film, it is a gorgeous, almost spiritually mesmerizing kind of film too. Its problem is that it's an insider's view of a community whose values and approaches (particularly its sense that a woman's goal in life is to marry and have children) are hard for modern viewers to sympathize with.

In the story, Shira is one of three daughters of the prosperous Rabbi Aharon (Chaim Sharir). Her sister Esther (Renana Raz) dies in childbirth leaving a baby, Mordechai, and her husband, Yochay (Yiftach Klein), in need of a new wife to care for the child. Indeed Shira does function like a Jane Austen heroine, in the sense that she is headstrong and resists the urging of her mother Rifka (Irit Sheleg) to agree to marry Yochay, who at first resists himself, then is taken with the young and pretty Shira, and humiliated when she lets him declare his attraction and then says she isn't interested and wants a marriage of virgin with virgin, as Yochay had with Esther. When other things don't work out, and the older sister Yocay isn't interested in finds a husband, Shira reverses her position, but not before she has been repeatedly stubborn with everyone on the issue. It is like Jane Austen, and it isn't: the final decision seems en emotional giving in to pressure, to "fill the void," rather than something that happens through growing up and learning moral lessons.

The fact is, as Weissberg notes, that despite the accomplishment of this film, its bias toward an extreme religous sub-group will be off-putting for many. However while the director is ultra-Orthodox, the actors are secular. Fill the Void debuted at Venice, and was shown at Toronto, where Mike D'Angelo gave it a disapproving 43 (I'm tempted to agree), with the Tweet review: "41. Like watching a film about freed slaves who opt to remain on the plantation for the good of the white family." I think he means Shira frees herself, by refusing Yochay initially, and her reversal and decision to marry him is like opting "to remain on the plantation for the good of the white family." I do not fully understand Hebrew, but my ability to follow it with the help of subtitles made me wonder if the dialogue here had much complexity. Notable is the repetition of the verbally identical formulas at all key moments in people's lives, and the very simple sentence structure of the dialogue. Jane Austen, with her wit and irony, this is absolutely not. Despite the richness of Jewish humor, this community as shown is not one favoring subtlety. Which is okay; but how primitive can you be in Tel Aviv (where this is set)?

The film debuted at the Jerusalem Film Festival, and reportedly "wowed" the audience at Venice, when it showed several months later there, and Hadas Yaron got the Best Actress award. The film has gotten good reviews in each festival venue, including New York and Toronto; perhaps somewhat less so when shown at the London Film Festival. Scheduled to be Israel's entry in the 2013 "Best Foreign Film" Oscar competition. Screened for this review as part of the main slate of the 50th (2012) New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, October 2012. The film has been bought for US release by Sony Pictures Classics.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-25-2024 at 10:27 AM.

-

Joachim Lafosse: OUR CHILDREN (2012)

JOACHIM LAFOSSE: OUR CHILDREN (2012)

NIELS ARESTRUP AND TAHAR RAHIM IN OUR CHILDREN

Letting things go too far

Our Children/À perdre la raison, starring Émile Duquesne, Tahar Rahim and Niels Arestrup is the slow-burning story of a family that gradually descends into hell. Elements of colonialism, gender roles, and psychological conflict are blended in a screenplay freely based on a news story from Lafosse's native Belgium known as "L'Affaire Geneviève Lhermitte." Viewers can debate what actually happens, but the trouble all begins when a wealthy doctor raises a young Moroccan, who falls in love and marries, and the couple live with him as his dependents. Lafosse seems to trade in unhealthy relationships and adults that are irresponsible. That was the case in Private Property, in which Isabelle Huppert is a mother more interested in affairs than raising her sons, and in Private Lessons, where thirty-somethings become unnaturally close to an adolescent boy whom they teach about sex. In fact having seen these two films helps one understand what's going on in All the Children. Lafosse is interested in boundaries, and what results when they're not respected or properly established within a claustrophobic hothouse environment. He takes his time with this one. It's interesting to see Niels Arestrup and Tahar Rahim, who played the Corsican mafia boss and his Moghrebin prison prottégé in Audiard's A prophet, back together again in a very different father-son relationship as the Belgian doctor and his boyish Moroccan immigrant dependent. For the initially vibrant young woman Rahim's character marries, who deteriorates in a situation that destroys her self-worth, Lafosse chose Émilie Duquenne, the Cannes award-winner from the Dardenne brother's Rosetta, who is the one who brings the drama to its muted but disturbing climax.

The film begins with four small coffins shipped to Morocco, so we know what happens, but for most of the time that is not thought of, though Morocco is a constant indirect presence. Mounir (Rahim) is like a pampered adopted son to André Pinget, the doctor who has raised him at his home. But as the action gets started Mounir has just failed a medical training program, and André takes him into his office as a kind of secretary. This weakness or the young man, and the older man's affectionate and protective relationship with him, leads to Mounir's staying on with André after he marries Murielle (Duquesne), a schoolteacher. And then the children begin, one after another in rapid succession, three girls and finally a boy.

The three main actors are fine, and Lafosse's scenes count not so much for what happens as for the atmosphere and the gradual feeling about the situation, a smile, a hug, a moment of congratulation that feels off. It's cozy and nice, full of affection. André is so generous he gives the baby and Murielle jewelry and Mounir a valuable watch when it's born. Rahim, the innocent protégé who becomes a powerful boss, seems spoiled and weak here, but also sweet, innocent, and happy. Murielle is harder to figure out. Eventually she will crumble, and her final deterioration comes through Morocco, which is also where André shows his dominance and colonialism. After moving to a house, which Mounir is given major ownership of but André also lives in, the Murielle feels just as stifled. The doctor is even Murielle's primary care physician. It seems the "our" in "our children" means André's and Mounir's. Slowly there are hints of nastiness from André. Murielle and Mounir want to be independent of him, but however they may try to do it, they can't risk André's threat of cutting them off completely. It's a situation that Mounir always thrived on. But Murielle is psychologically fragile. Ever since the time when her negligence causes one of their young children to fall down some stairs, she has a morbid fear of harming them. After the living situation becomes oppressive she deteriorates mentally, taking a leave from teaching and having trouble dealing with the kids.

Lafosse obviously wants to take on various topics, the status of immigrants in Belgium, how many kids one should have, the risk of non-traditional families, the treatment of mental problems. There is no one explanation in the film for Murielle's decline or for her tragic action, but contributing factors obviously are the claustrophobic living situation, the pressures of raising four small children at once, her husband's and her nebulous status, and André's controlling tendencies. Or she may just be inherently unstable. (It's all pulled together by recurring music from Scarlatti's operas, at once comforting and haunting.) What's interesting is the way Lafosse shows the slightly strange dynamics of the household, the push and pull between the doctor's kindness and his will to dominate. This is where the director excels. In this more multi-layered narrative, he proves not so good a storyteller, even with the collaboration of Thomas Bidegain of A Prophet. However this is a richer film than the previous ones, glossier, more complex, covering a period of years, and with a powerhouse cast; hence this new film is a real step forward for a director who's building up a coherent body of work but so far has not been known in the US.

After debuting in the Un Certain Regard series at Cannes in May 2012, Our Children/À perdre la raison opened in Paris in August, to generally good reviews (Allociné critics rating: 3.7). its first American appearance is in the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-01-2012 at 12:26 AM.

-

Lee Daniels: THE PAPERBOY (2012)

LEE DANIELS: THE PAPERBOY (2012)

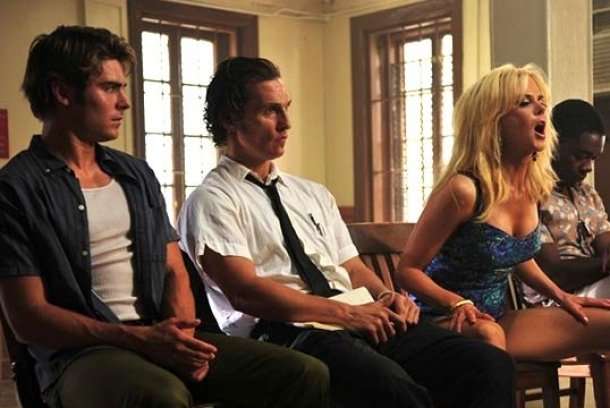

EFRON, MCCONAUGHEY, KIDMAN AND OYELOWO IN THE PAPERBOY

Humid investigation

The Paperboy is an enjoyably lurid southern noir set in the mid-Sixties from Pete Dexter (who collaborated on the screenplay) with additional touches added by the director of Precious, who has a taste for the highly colored ant the shocking. If you want to see Nicole Kidman pee on a half-naked Zac Efron this is your movie. But Kidman is excellent as the tacky bleach-blonde Barbie Doll death row groupie and Efron (Jack Jansen) is vulnerable and sweet as the younger brother of Miami newsman Matthew McConaughey (Ward Jansen), who comes with Yardley, a black colleague apparently from London (David Oyelowo) to investigate a murder case. The sleazy, odious inmate is played by John Cusack (Hillary Van Wetter). Of course in this Florida town in this year a black colleague is provocative enough; and it's Daniels' touch, not in the Dexter novel, that he should be black. The peeing scene has a therapeutic purpose: it's to counteract toxins from a jellyfish Jack (Zac) has met up with while swimming. Daniels' finest touch is his use of the excellent Macy Gray as Anita Chester, the Jansen family maid, who also does the voice-over narration, and the best scenes are ones of familial intimacy between Anita and Jack. Everybody is good, McConaughey doing his Good Old Boy drawl, Oyelowo infuriatingly cocky as the British-accented colored man, Cusack a scary piece of swamp muck Hilary's family comes from the swamp and lives by gutting alligators to sell for shoes and handbags). Daniels at times tries to evoke Seventies B-pictures. I don't think you can take all this seriously, despite the strong hints at many turns of Sixties South racism, but there's something unique about it, and it entertains.

Charlotte gets the "paperboys" to come following a romantic correspondence with Hillary, and when they come into town comes wearing a tight dress and bearing big boxes of research into the case. But the newsmen seem distracted, and not very interested in finding out the truth. Jack, a former swimming star kicked out of college who's not doing much but delivering papers, is enlisted to be the reporters' driver, and he falls madly in love with Charlotte and moons for her or sexes for her till finally he gets her "Okay, but just once." Meanwhile there is Anita's humorous voiceover narration, and the present-time Anita's many cozy little scenes with Jack, while unexpected or not so unexpected truths emerge concerning Ward, Hillary, and Yardley.

The movie is great in individual scenes, but doesn't move so well from one to the next. For a noir, The Paperboy lacks urgency or narrative drive. This won't convince anybody it has contemporary relevance as did Lee Daniels' previous film, the 2009 Precious, but again there may be some Oscar mentions. Along with condemnations: the critics are not joining up to praise The Paperboy. Rex Reed has launced one of his diatribes against it: '"This raunchy dreck, cut from the same disposable toilet tissue as the recent trailer-trash creepfest "Killer Joe," is a leap downhill from "Precious,"' he intones. Indeed McConaughey is also featured with Zac Efron in Killer Joe, but that's Tracy Lett, and that's a different kettle of rancid catfish.

The Paperboy debuted at Cannes and was also shown at Toronto. Like Precious, it's included in the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review. It begins a limited US release October 5, 2012.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-23-2012 at 12:36 AM.

-

Abbas Kiarostami: LIKE SOMEONE IN LOVE (2012)

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI: LIKE SOMEONE IN LOVE (2012)

TADASHI OKUNO, RIN TAKANASHI, AND RYO KASE IN LIKE SOMEONE IN LOVE

Changed perceptions

Sometimes a director transplanted to another culture might lose his identity but Abbas Kiarostomi does very well in Like Someone in Love, his study of fantasies and miscalculations shot in Japan. Notably, he combines an inexperienced actor and a real pro with a third principal who never played a lead in decades as an extra, and the effect is thoroughly fascinating. Like Someone -- the Ella Fitzgerald standard -- but nobody really in love, here. What we have is three people, at least one of whom is being taken for a ride. If you see this as alternate couples, maybe there's a link with the director's previous prizewinner, Certified Copy. Both films are about people who are not what the seem. But this new one doesn't have the Mediterranean gloss, pretty settings and enjoyable intellectual identity puzzle. . No Pirandello here, only a girl, a student from the country who moonlights as an escort, spending an apparently platonic evening with an old man, and a young man who thinks he's her fiancé, or who is, but is unaware of her side job, and when he finds out about it, is enraged. This is a rueful look at humanity's foibles and follies, not a pretty puzzler. It has less audience appeal. It shows Kiarostami as a master of the car scenes he loves to do and of bland, repetitive dialogue, but despite the mark of the director's style and polished execution, it's a bit difficult to ferret out a point here, in part because of the shallowness with which the characters are presented.

When the film begins Akiko, the student/escort (Rin Takanashi), is talking to someone in a little nightclub. It's Nagisa (Reiko Mori), her boyfriend, but we don't know that yet and we don't even know at first who's talkng. Kiarostami playfully withholds information and keeps the viewer at one remove from the characters. She is here to receive her assignment, which is to see retired sociology professor Takashi Watanabe (Tadashi Okuno). On the long cab ride, she listens to her phone messages. These consist mainly of a series of progressively more sad calls from her sweet country grandmother, who has come to town to see her, but only for the day, and at the end is about to take the train home after ten p.m. After the last message, when grandma reports she is still sitting near a gate waiting, Akiko has the cabbie circle the station. A pointed irony is that in the station grandma has seen one of the little flyers Akiko put around on her first forays in the escort business, and it says "Akiko" and has her picture, but grandma innocently says it's just a coincidence, and can't be her. This flyer comes up later, because one of the workers in Nagisa's garage has shown it to him.

When Akiko gets to the professor's, he wants to entertain her rather than have sex, though she goes to bed, after a conversation about a painting -- and she's very tired and just wants to sleep. The two are totally at cross purposes. The next morning Watanabe offers to drive Akiko anywhere she wants to go, obviously eager to spend more time with her, and she has him chauffeur her to an exam at school. There she runs into Nagisa, who's angry, it turns out because she hasn't answered her cell all night - doubtless a frequent occurrence. Nagisa sees Watanabe, and eventaully gets into his car and has a conversation about Akiko; he assumes Watanabe is her grandfather. Watanabe keeps his identity vague, but advises Nagisa not to marry Akiko, but merely to enjoy her -- while she lasts, as it were.

We are to think that probably Nagisa's time at his garage with the chap who has the flyer and a frank chat with Akiko when they meet afterward for lunch leads to a fracas, and Akiko summons Watanabe from his flat to pick her up, nursing a swollen jaw, shaken, and shortly pursued by a furious Nagisa, whom, however, we hear but do not see again.

This little tale with its slow revelations to us and to the characters (or Nagisa, anyway) is done with much subtlety, but it also has a chilly, pointless quality, and again leads this reviewer to say yes, Abbas Kiarostami is a master, but of what? and what does it matter, if this is all? This film is intricate and clever, but also somehow inconsequential. Like other Kiarostami films, it is a short-short story on acid, its tiny details blown up and drawn out.

There's no faulting the craft here, the elegant night photography, the skill with which the intimacy (and loneliness) of a car interior is exploited, and the acting. Tadashi is pretty , and in Japanese style, maddeningly tempting and aloof. Okuno is the long-time movie extra, who was tricked into playing a starring role by not revealing the extent of his performance. Probably no one else could have been better, more humble and natural, as this sweet, befuddled old man. Kase, a veteran of many roles, is strong in the only role that requires strength, because Nagisa has values, hopes, and desires and the will to see them through -- though while he thinks Akiko is naive (one of Kiarostami's many little ironies), he is the one who's been tricked.

Like Someone in Love, in Japonese, 109min, debuted at Cannes; had a theatrical release in Japan Sept. 15; debuted Oct. 4 in the US at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review; opens in France Oct. 15. Critical reception in France was fair (Allociné press rating 3.3) but some of the most sophisticated publications praised it the most highly (Les Inrockuptibles, L'Humanité, Libération, Cahiers du Cinéma). The US opening is Feb. 15, 2013, which follows an Abbas Kiarostami retrospective at the Film Society of Lincoln Center from February 8-14.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-23-2014 at 11:39 PM.

-

Olivier Assayas: SOMETHING IN THE AIR (2012)

OLIVIER ASSAYAS: SOMETHING IN THE AIR (2012)

LOLA CRÉTON AND CLÉMENT MÉTÉYER IN SOMETHING IN THE AIR

After Carlos: Assayas does himself in the Seventies

A couple years ago Olivier Assyas impressed the world with his dashing mini-seires biopic about Carlos the Jackel, Carlos, a tale of radical agit-prop and sabotage in the Seventies by a leftist master of mayhem. But despite the success of Carlos it didn't enable Assayas to show his own role in this period, so he made Something in the Air -- original title Après mai, "After May" -- where an alter ego experiences the moment more as the writer-director himself did. This time there are some explosions, but nothing as spectacular as the radical acts in Carlos, though there is vandalism and Molotov cocktails and a blown-up car. The opening political stunts are carried out by lyçée students. Après mai has nothing to do with radical terrorism. It's a story of art and politics, music and love affairs, and how for a 16-20-year-old, they're all mixed up together. If Carlos was Assayas' ultra-cool-terrorist-in-the-Seventies movie, this is his talented-but-confused-French-youth-in-the Seventies movie, and it takes decidedly second place. The content of this second movie is no match for that of the first. Moreover though I know Garrel's film is about 1968 and its immediate aftermath rather than the early Seventies, it was hard not to think of his deeply romantic and compulsively gloomy black and white film Regular Lovers while watching this. And though the newcomer Clément Métayer, who plays Gilles, is engaging and soulful in his sallow, long-faced way, he is no match for Louis Garrel (though he's more like a real French teenager and less like the profile on a Byronic Roman coin). And despite her classic face neither can Lola Créton, who plays Gilles' girlfriend Christine, compete with the subtle charms of Clotilde Hesme. Assayas' new film is beautiful, detailed, and accomplished, almost too rich in splashy details. It might have been move evocative with a lower budget. Nonetheless the chops Assayas built up as a vibrant film historian in Carlos are still evident here, so although no match for the previous film, this is still impressive work with richer detail than most other films of this genre.

Something in the Air is a fumbling and unhelpful title. The actual one, "After May," states the movie's real theme: the disillusion and long search for meaning that followed the heady times of the Sixties. These high school students are a little like the much later Italian ones in Gabriele Muccino's appealing (and swift and economical) debut Come te nessuno mai/Forever in My Mind, who envy their parents' Sixty-Eight activism and start a school revolt, with all the trappings, to relive those days. But Muccino's film knows where the boys' minds are: for them politics is an excuse to lose their virginity. Assayas' world is more complex, and Après mai has a lot of serious discussions of revolutionary theory and political strategy. These kids are older and more serious than Muccino's younger brother, Silvio, with his little earring and his urgent desire to get laid. Gilles is a serious artist, with, like Assayas' own, a father in the movie and writing business; they work together some, and argue about how good or slapdash Gilles' father's screenwriting or Simenon's Maigret novels are. Gilles is leftist in spirit, but art is the stronger calling, and he sticks with it, after the early activism and the continuing friendships with guys who make movies about labor unions in Italy or go to Afghanistan or Nepal, or somewhere.

Assayas gives Gilles/Clément a lot of face time, but he's largely a vehicle for a travelogue of European youth in the early Seventies, and there are some great vinyl rock anthems, various pairings-off and those ardent political discussions. But most of all the director relies on big scenes, climaxing in a summertime visit to the family mansion in the country of Gilles' first failed romance Laure (Carole Combes), when a spectacular hippie drug party is going on, complete with acres of candles, haystack bonfires, and finally a fire that invades part of the house, forcing Laure to leap from an upstairs window (that's all of her for a while). This is a flashier, period version of the party at the end of the director's Summer Hours, a simpler film but a more fully achieved one because it knows what it's doing. But though Après mai/AKA/Something in the Air is a big sprawling shambles, it evokes the Seventies in multifarious and true ways. I think I would watch it again. After all, it's in French, and the French do this sort of thing, the politics, the art, the angst, the clothes, so well.

Something in the Air/Après mai , in French with some English, 122 min., debuted at Venice and was shown at Toronto. Screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was also included as part of the preferred group of the Main Slate. Released in France, Belgium and Switzerland Nov. 14, 2012, and in NYC and LA May 3, 2013. The French critical reception was generally very positive: Allociné press rating 3.8. based on 24 reviews.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-20-2015 at 09:22 PM.

-

David Chase: NOT FADE AWAY (2012)

DAVID CHASE: NOT FADE AWAY (2012)

Growing up in a band that doesn't make it big

David Chase, who created the super-successful and groundbreaking HBO series "The Sopranos," has chosen a nostalgic Sixties picture about a garage band for his debut as a movie director. It is a nice little film and has some sharp dialogue, but it trods familiar ground. The one thing that makes it stand out is that this one band for a change belongs to the vast majority that do not go on to become famous, like the Rolling Stones whose songs they covered at first. Instead they basically do fade away. They prove to be not ambitious and hard-working enough to pay their dues at cheap clubs like their idols (or the Beatles in Hamburg), their dissolution sealed with several dropouts and a lead singer who goes to California to study film.

This is an interesting and valid topic but of course runs the risk of being less interesting than the dramatic success stories. Not Fade Away itself fades when compared to a film like Anton Corbijn's 2007 Control, about Joy Division and Ian Curtis, the lead singer who committed suicide just when the band was becoming known (played by Sam Riley in the film). Chase's protagonist, Douglas (John Magaro), is a sometime ditch digger at a golf course semi-obsessed by "The Twilight Zone" who becomes the lead singer of the band. He's no Ian Curtis. He can sing surprisingly well and has also got a nice East Coast edge to his voice when he speaks, but he's just menat to be an Italian-American guy from New Jersey, and to prove it his father Pat, manager of a Pet Boys shop, is played by James Gandolfini, Chase's "Sopranos" star. But that Douglas isn't a future rock idol is the point. Instead the Jersey boys of Chase's movie serve as touchstones for a review of the early Sixties, the period from their late teens to early twenties, through a variety of hair styles and outfits, at a time when Kennedy was assassinated, Vietnam heated up, and rock and roll took on the importance it still has today.

Like the cast of Control, this one learned to play their instruments and sing and perform the music they're seen performing in the scenes. That's a plus. A minus is the extent to which Chase piggy-backs into the period and a sense of the music the same way the characters do, by using clips at key moments. The movie opens with a clip of a Fifties salt-'n-pepper rock and roll band. And when the young band performs one of their covers the sound is spectacular. -- too spectacular. Little discernible effort seems to have been made to duplicate the sound of primitive, limited amplification equipment and instruments.

The other cast members are not bad. Will Brill plays a rich, obnoxious guitarist and Jack Huston is touching as Eugene, the would-be lead singer who can't quite cut it. Bella Heathcote is cute and serviceable as Douglas' girlfriend Grace, who's always liked him and moves in when he becomes visible as a musician. There are mixed messages but at different points she tells him "time is on his side" (echoing the Stones) and she believes in him. Dominique Mcelliogott provides necessary period color as her nutty, drug-damaged sister, whose parents have her committed.

Part of the period portrait is of course the cultural and generational conflicts, Grace's parents with her dysfunctional sister, and Douglas with his dad. There is the obligatory moment when a teenage girl tells the adults at a barbecue that "coloreds" are now to be called "African Americans" (historically inaccurate) and that "fag" is a term that's "unfair to the homosexual community" and should be replaced by "gay" But this sort of thing and the slight references to car culture are secondary. Chase's main object is to declare that he loves rock and roll (with the sui generis sound track of his own personal favorites to prove it) and that the music was the heart of the era and of coming of age for his generation.

It is the essence and distinction of the story that for this band there is no big break, only the usual moments of conflict among band members over roles and direction. There are few original scenes. One memorable one occurs when Douglas' dad (Gandalfini), who has lymphatic cancer (barely acknowledged in the plot except for him mentioning it), takes his son to an Italian seafood restaurant so they can have a "serous talk" about what it might be like for him to take over the family with his father gone. The conversation isn't very memorable, but the moment is. The climactic scene comes when the boys perform for a music producer, and he talks to him afterward. That they'd get a contract is their fantasy. They really aren't that good. And they have, so far, only one original song. He tells them to go and perform in dive bars seven nights a week, to get the experience. Though in the somewhat patchy screenplay it's not openly stated, but they're really not as a group willing or able to do this, and so this is a pivotal moment between rock and roll dreams and everyday reality.

The original song was composed by Steven Van Zandt, a "Sopranos" cast member and the musical guru for the film, who helped the actors develop into a band and even got a drum coach for Magaro who played with the Beatles. Working together for three or four months before the sixty-day shoot, the core cast of guys became friends, and their camaraderie no doubt contributes to the spirit of the film, which is very positive. But it's hard to say -- is this movie a success? I'd say not so much, but it is what you make of it, since it's riddled with pop touchstones and standard rocker coming of age scenes.

Prodouced by Paramount and distributed by the Weinstein Company, Not Fade Away is scheduled for a limited US release December 21. Screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it premieres and is one of the Main Slate films.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-23-2014 at 11:17 PM.

-

Michael Haneke: AMOUR (2012)

MICHAEL HANEKE: AMOUR (2012)

JEAN-LOUIS TRINTIGNANT AND EMANUELLE RIVA IN AMOUR

[S P O I L E R S]

Loyalty to the end

In Amour Michael Haneke has delivered another masterpiece, notable this time for its humanity and sweetness as well as austerity. The latter is a kind of respect, because nobody is allowed to matter in this movie but a dying old woman and the man who cares for her. There are no phone calls, appointments, doctors, or really any scenes outside the couple's big, comfortable, elegant old Paris apartment, after the first scene. Though this is a grueling and painful watch, it's also uplifting. "Amour," love, really is the subject, the ultimate test and ultimate proof of what love is. As Mike D'Angelo puts it in the excellent review he wrote for AV Club from Cannes, where this won the Palme d'Or, this film "movingly illustrates the pragmatic sentiment that Terence Davies inserted into his recent adaptation of Terence Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea, viz. that true love isn’t candy hearts and flowers but wiping someone’s ass when they can no longer do it themselves." That's what happens to Anne (Emanuelle Riva), and her husband of many years, Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is the person who does the job.

It happens after a concert by Alexandre (Alexandre Tharaud), focused on Schubert, and he turns out to have been a former student of Anne's, she and Georges both music teachers, now retired. When they come home, someone has tried to jimmy the lock of their front door -- a Haneke-esque clue to impending danger, a reminder perhaps that since they're both eighty-something, the protective shell outside their existence is eggshell-thin. The next morning at breakfast Anne has a sudden period of catatonia. Tests (we don't see them) reveal the need for an operation, but it's not successful, and when she returns from the hospital, begging Georges never to let her go back, she is paralyzed on one side from a stroke and in a wheel chair. Things will go downhill from there. At first Anne's hair is still beautifully styled, and she can sit up and eat, and talk normally. She asks for photo books and looks at their personal and family record. "It's beautiful, she says. This long life."

The specific incidents and scenes are important of course, but it won't convey much to describe them here. What this is really about is the way Georges remains present, taking on as his one duty caring for his wife, whatever happens. This isn't only the ultimate test but also beyond him; nurses have to come in part-time. Georges is very nice but he can be mean sometimes, Anne remarks. He is harsh with her once, when she has reached an almost ultimate state of decline and refuses to eat or drink. All Georges is trying to do is to protect Anne from being put in a hospital, or a nursing home, or a hospice, keeping her at home, with him.

It's also Haneke-esque how harshly others are judged. One caregiver is okay, but the other is deemed worthless. Their daughter Eva (Isabelle Huppert) is well-meaning in her way, but just an annoyance. Other family members are to be avoided. The pianist student who visits and sends a note is found wanting because, not unlike Eva, he fusses improperly. Haneke-esque too is the noble but drastic solution of euthanasia Georges resorts to, to end Anne's suffering. After another stroke she can't speak and simple moans "It hurts" all the time, up all night, sleeping mostly during the day. Nothing to be done. Beckett would understand.

Riva's performance is largely a mechanical one, reproducing the effects of paralysis and mental degeneratioin. To Trintignant, who is 82 and considered himself retired since he did Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train for Patrice Chéreau in 1998, falls the burden of depicting the bravery, the endurance, the steadfastness, the sanity, and the love of this husband. And this the great actor of My Night at Maude's can do. His own age plays a key part: the actor himself has some difficulty walking, making Georges' lifting Anne the more heroic.

Amour is realistic, perhaps, compared to Beckett, but stylized, in its choice of this naturally-lit grand appartement bourgeois, in the exclusion of outside annoyances, or locations outside the narrow confines. There are a few depatures: several brief haunting dream sequences and a hallucination; a beautiful opening-up through a series of shots of landscape paintings in the apartment. There is a symbolic stray pigeon that comes in a window from the courtyard, twice. The austerity is a beauty that makes the painfully difficult experience watchable.

This is unmistakeably Haneke, but as D'Angelo notes for the first hour seems unlike him in its sweetness; but then becomes "Haneke-grueling." The whole film's tenderness and intimacy are the more striking coming from this director. And though there have been many movies about accidents, illnesses, old age, and death, no one has told this story before, following the experience of the spouse-caregiver through to the end -- though the film's final end, typically for this director, is kept somewhat mysterious. As the Variety reviewer Peter Debruge points out, what happens here is not unlike Haneke's 1989 debut, The Seventh Continent, but the "unforgiving nihilism" of the earlier film has been replaced "by a sense of deep concern."

Amour, 127min, debuted at Cannes, has been in other festivals, and was screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, Oct. 2012. It opens in France Oct. 24, the UK Nov. 16, US (limited) Dec. 19.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-07-2020 at 08:37 AM.

-

Sally Potter: GINGER & ROSA (2012)

SALLY POTTER: GINGER & ROSA (2012)

ALICE ENGLERT AND ELLE FANNING IN GINGER & ROSA

Red hair and tears

Sally Potter's Ginger & Rosa is a movie that's both ambitious and narrow. It primarily focuses on the quite limited lives, momentous only to them, of two teenage girls. But Potter chooses to stage her dual, feminine coming-of-age story in the England in 1962 for a reason. It's self-consciously a moment of transition -- on the cusp between the tail end of the Fifties, when the Brits were still struggling and haunted by the War, and the full-on Swinging Sixties, with their war protests, miniskirts, and Beatlemania. Can the vivid and luminously photographed story -- whose nice handheld camerawork (by Andrea Arnold dp Robbie Ryan), earth colors, and intense closeups are a pleasure to look at -- bear the weight of social commentary? Not so well, it turns out. Despite the distinctive visuals, nice (if inexplicable) jazz music, and accomplished acting, Ginger & Rosa is both claustrophobic and sappy. Its point that radical thinkers can make unreliable husbands and fathers is made in a trite and obvious way. Its constant harping on peace marches, nuclear terror, and the Cuban Missile Crisis hardly provides a rounded sense of the period. And it's a most peculiar movie about schoolgirls that never shows them really looking at boys, listening to pop music, or even going to school. Is all this what's meant by "auteur" -- a filmmaker who's willful and blind? Ginger & Rosa is a stylish visual poem, pretty and very personal, but also very limited.

After a while the eyes of Ginger (the young American actress Elle Fanning, blond hair dyed scarlet) seem to run with tears in nearly every scene. And for good reason. Her father, Roland (Alessandro Nivola, another Yank playing Brit), a pacifist professor formerly jailed for war resistance, is not so moral in his private life. He is mean to her mother Natalie (Christina Hendricks, the super-busty Joan of "Mad Men") and then leaves her, and gets Ginger's best friend Rosa pregnant. (Rosa is played by Alice Englert, the beautiful daughter of Jane Campion, but doesn't make much of an impression). Ginger, a redhead like her mother, joins a youth nuclear disarmament group . She also wants to be a poet; she reads T.S. Eliot. When Roland is having sex with Rosa she recites from "The Hollow Men": "This is the way the world ends/This is the way the world ends/Not with a bang but a whimper." Or maybe with both? No pun intended, one assumes, but it's an awkward moment.

Perhaps the self-centeredness of the girls is realistic for their age, but it further narrows the film's scope. Roland is a potentially more interesting character. He is noble, but an ass, and Nivola plays him sympathetically, though he still winds up seeming thoroughly despicable. He glows in the false light of Ginger's need for a father and the sublimated sexuality of Rosa's "admiration" of him. Roland conveniently has a boat on which the girlfriend and the father can get it on. Protest marches and meetings exist for the girls to be impressed by a vibrant young radical student leader (Andrew Hawley). Ginger is sure the world is about to end -- because she thinks so. An American leftist lady her father knows, Bella (Annette Benning, wasted and her character's role undefined) points out she has said the world as they know it "might" end, not that it "will" end.

There are a couple of other characters, Ginger's gay-couple godparents Mark and Mark (Oliver Platt and Timothy Spall). Platt plants a chaste kiss on Spall's forehead to indicate their relationship. In the film's rather sketchy structure, Mark and Mark hover nearby at moments of crisis to expand the movie's sense of a non-traditional family. When Roland starts sleeping with Rosa things get a bit too non-traditional, more like borderline illegal and almost incestuous. But again this being all about a girl's self-centeredness, the main point is that this relationship upsets Ginger. For once Rosa has struck out on her own. Most of these people are silly and superficial, and even when they take a valid stand, they do it in a self-centered way. If this is a feminist film, it doesn't make its case very well.

Ginger & Rosa, 90min., debuted at Telluride and played at Toronto and also in the 50th New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review Oct. 8; it comes to the London Film Festival Oct. 13, and releases in the UK Oct. 19, 2012.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-08-2012 at 04:48 PM.

-

Dror Moreh: THE GATEKEEPERS (2012)

DROR MOREH: THE GATEKEEPERS (2012)

AVI AVALON, SHIN BET HEAD 1996-2000, IN THE GATEKEEPERS

Security chiefs explain why Israel's not secure