-

Benoît Jacquot: Farewell, My Queen (2012)

BENOÎT JACQUOT: FAREWELL, MY QUEEN (2012)

LÉA SEYDOUX AND JULIE-MARIE PARMENTIER IN FAREWELL, MY QUEEN

The French Revolution from an odd angle

History books often ring false because they're narrated from an omniscient point of view that favors great men and power. Farewell, My Queen/Les Adieux à la reine, a 2002 Prix Fémina-award-winning novel by Chantal Thomas adapted by Benoît Jacquot, seeks to describe Versailles at the precise moment of the storming of the Bastille and the chaotic days thereafter (July 14-17, 1789) from the viewpoint of a very minor insider -- the "reader" for Marie Antoinette (Diane Kruger). Sidonie Laborde (Léa Seydoux) lives in a humble room at Versailles; her only possession of value is a nice clock. Ironically, Seydoux herself is a real film princess, being granddaughter and niece of the combined ruling Gaument-Pathé cinema families. Sidonie is nobody, but due to her job she regularly spends time alone with the Queen of France, whom she idolizes and is dedicated to serving. By being situated on the edge of great events instead of staring at them head-on we are enabled to view a key moment of French history from a new angle. The advantage is that the picture provided feels more authentic. And like Sofia Coppola, Jacquot had the privilege of shooting actually at Versailes: the glittering hallways and gilded and chandeliered rooms enfilade are the real stars of the show.

The disadvantage of Thomas' narrator is that she's limited and unreliable: she's blinded by her super-loyalty and her minor role in the court provides only fleeting views of main events. But Jacquot, whose filmography is uneven, nonetheless scores a relative success here by handling the material simply. He relies on a sure-fire mix of candlelight and gowns, wise old men and beautiful young women. He even throws in one sexy young man, a fake Italian called Paolo (Vladimir Consigny) who mans a gondola and sings in Italian but is really a French nobody, like Sidonie, whom he meets and makes a play for. They are all ready to get it on in a hallway, but it's a sign of how chaotic and frightening events have become that even that quick youthful coupling is interrupted.

Sidonie enjoys the friendship of a denizen of the royal records, Jacob Nicolas Moreau (Michel Robin), an historian and ardent royalist (though we aren't told that). She takes directions from Madame Campan (Noémie Lvovsky), first lady of the bedchamber (who wrote memoirs of Marie Antoinette, though that's not mentioned either). Jacquot's film is a succession of swift scenes in which moments of chaos and growing terror at court alternate with the routine frivolities. Rome is burning, the court is fleeing -- and the faithful few are sewing. Sidonie and her colleague Honorine (Julie-Marie Parmentier) continue to work on an embroidery of a dahlia to delight the Queen. Marie Antoinette (author Thomas perhaps riffing here off the many libels cooked up against the Queen later as pretexts for her execution) nurtures a virtually open lesbian attraction for the Duchess Gabrielle de Polignac (Virginie Ledoyen). The Duchess, in her special green silk gown symbolizing hope, envy, and a dozen other things, is far more interesting to the Queen than the plump, pasty-faced Louis XVI (Xavier Beauvois), and, unfortunately for Sidonie, eclipses her in the Queen's affections as well.

The best scenes are the ones in the dark corridors behind the halls and mirrors and great rooms enfillade where aristocrats and servants, increasingly confused about who is which, hover clutching candles and trading rumors of who has fled and who has been offed by the revolutionaries.

Approaching the events crabwise captures the curious mixture of order and disorder that doubtless indeed prevailed. Rumor is how people know what is going on. The physical "pamphlet" listing 200-odd aristocrats who must be beheaded is read by an aristocrat (Jacques Nolot) in the chaotic jumbled corridor amid the flickering candlelight. Madame Campan says this must be kept secret. It's later given to Marie Antoinette and she throws it into the fire. She decides to flee to Metz (and gives orders for items to bring including a coffee pot, teapot, and chocolatière), but the King's decision to remain at Versailles and go to Paris alone frustrates that hope. Several scenes not involving Sidonie are still from her POV: we see Marie Antoinette and the Duchess de Polignac alone together because Sidonie is spying through a doorway. Anyway this is a film of atmosphere and suggestive glimpses rather than action. The point is that the rulers, used to trivial pursuits, have no real idea how to act in the crisis. Threatened with beheading, the Queen burns love letters and gathers her jewels. Sidonie's world is crumbling but she still focuses all her efforts on gaining more favor with her mistress. The story dutifully provides a kind of surprise ending for Sidonie that does not end her indirect link with the higher-ups.

The film maintains well its sense of disorder and panic -- the latter unnecessarily underlined with constant tremulous mood music. One would need a novel or a mini-series to convey fully the complexities of mind and personality behind this young woman narrator, who like all the rest is only glimpsed but clearly is as smart and well-read and crafty as she is loyal. The end result of the focus on a zigzag of fleeting moments is that the viewer is intrigued but not much moved.

Benoît Jacquot's Farewell, My Queen/Les adieux à la reine, a French-Spanish coproduction, was the opening night film at Berlin 2011. It opens in French cinemas March 21, 2012, and was watched for this review at a press screening for the March 1-11, 2012 UniFrance-Film Society of Lincoln Center series, Rendez-Vous with French Cinema. Public screeings of the film at the Rendez-Vous at the Walter Reade Theater (WRT) at Lincoln Center and the IFC Center in lower Manhattan:

*Fri., March 2, 6:30pm – WRT; *Sat., March 3, 1:30pm – WRT; *Sat., March 3, 7pm – IFC; *Sun., March 4, 6pm – BAM

*In person: Benoît Jacquot

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-13-2012 at 01:28 PM.

-

Muriel, delphine coulin: 17 girls (2011)

MURIEL, DELPHINE COULIN: 17 GIRLS (2011)

SOLÈNE RIGOT, JULIETTE DARCHE, LOUISE GRINBERG, ROXANNE DURAN, ESTHER GARREL IN 17 FILLES

Teen baby club in a French coastal town

From the sister team of Muriel and Delphine Coulin comes this first feature set in their home town of Lorient in Brittany based on a 2008 American news story about 17 girls at a Gloucester, Massachusetts high school who allegedly made a pact to get pregnant and raise their children together. The reporter who wrote the original story later made a documentary revealing there in fact was never any "pregnancy pact" among girls at the school. There were simply 18 unwed girls no older than 16 who got pregnant at Gloucester High that year -- an only slightly higher number than usual. The French film has been well received both for its cautionary social message and its warm performances and several memorable scenes. With its pretty jeunes filles en fleur and its luminous pastels by skilled dp Jean-Louis Vialard (who has worked with Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Christophe Honoré) strongly reminiscent of Joel Meyerowitz's photography classic, Cape Light, this is a film that's easy on the eyes. It seems unfortunate that a film aiming to bring home truths to the French audience is based on a false premise, is thin on background about the girls and lacks follow-up on what happens after the babies are born. Could they not have begun by getting the details right? But whether myth or reality, 17 filles is watchable and thought-provoking.

The town of Lorient has in common with Gloucester being a one-time port that is economically depressed, and teen pregnancies tend to be high among the poor. Another common feature is a lack of realism among pregnant teens about what child rearing will be like. That was true at Gloucester High and it's true among the girls of Lorient. The lycée girls see no future for themselves as adults in their town, and banding together in the intense friendship of teenage girls, they imagine a utopian commune in which they will raise their kids together, free of annoying adult pressure. 17 filles makes clear that this does not happen, though apart from the mishaps that occur to several of the girls, what does happen is not detailed.

In contemporary society poor girls can make their social errors with the firm illusion that they're exercising free will in so doing. And in 17 Girls its Camille (Louise Griberg of The Class), the prettiest, most clearly Alpha female of the lycée girls, who first proudly announces to her best mates up on the dunes that she's pregnant. She's the trend-setter. When the rejected girl Florence ((Roxanne Duran) claims she's pregnant too, her declaration gets her membership in Camille's five-girl inner circle. Getting pregnant becomes a gesture of defiance and a symbol of belonging to the in-group. The willingness of teenagers to self-sacrifice in order to belong has never been better dramatized.

There are funny scenes, like when a group of girls, once the project to get collectively enceinte has been agreed to, shock a clerk when they buy a large number of pregnancy tests at a pharmacy. As the school nurse, the ubiquitous Noémie Lvovsky (the madam in House of Tolerance and also in Guilty and Farewell, My Queen in 2012's Rendez-Vous) adds a note of bemusement and. . . tolerance. A gathering of school officials debate what the sudden rash of pregnancies means. When confronted by irate parents, who blame the school, the principal (Carlo Brandt) simply insists neither he nor the llycée is responsible.

Meanwhile the individual dramas play out. At a summer dance, girls determine to make boys get them pregnant. Given that the girls in the cast are all pretty, it's not surprising they succeed, except for one who later offers a boy 20, 30, then goes up to 50 euros for him to impregnate her. Camille's single mom (Florence Thomassin) is extremely angry. So are other parents who run a café. There are some good scenes between Camille and her brother, who has become a soldier in Afghanistan. The relationship between Camille and her brother is the only male-female relationship of any depth. Camille has an on-and-off boyfriend who proves loyal at the end, but otherwise no boys are present for the pregnant girls, one of the odd and implausible aspects of the film.

17 Girls was included in the Critics Fortnight at Cannes and received high marks from Paris critics when it entered cinemas December 14, 2011 (an excellent Allociné 3.8 rating). Reservations about the accuracy of the story can't detract from the fact that this is, as the French reviews nearly all say, a first film that is a warm and sunny and justifiably troubling "success." This might be contrasted however with the more probing exploration of teeange girls found in the films of Céline Sciamma (Water Lilies, Tomboy).

Delphine Coulin is also a novelist and her sister Muriel is a documentary filmmaker.

The film is included in the Unifrance-Film Society of Lincoln Center March 1-11, 2012 series, Rendez-Vous with French Cinema. Public screening schedule:

*Fri., March 2, 9:15pm – WRT; *Sat., March 3, 9:30pm – IFC; *Sun., March 4, 1pm - WRT

*In person: Delphine and Muriel Coulin

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-24-2012 at 12:50 AM.

-

André Téchiné: Unforgivable (2011)

ANDRÉ TÉCHINÉ: UNFORGIVABLE (2011)

ANDRÉ DUSSOLLIER AND MAURO CONTE IN UNFORGIVABLE

Téchiné, a bit off form

Unforgivable is adapted from a novel by Philppe Dijan (whose 37°2 le matin was the basis for Beineix's Betty Blue). In this new source Téchiné finds favorite themes: family tensions, amorous transgressions, personal doubts. He assembles an interesting cast including André Dussollier, Carole Bouquet, Adriana Asti. They deliver fresh, energetic performances, and are joined by young hopefuls like Mélanie Thierry and Mauro Conte, who also show how good Téchiné is with actors. The underlying theme from the novel by Dijan, something about a writer who gets blocked when he's in love, along with other implausible plot elements, doesn't go down nearly as well as the performances. This is recognizably personal work. But Unforgivable doesn't sing and excite us like the great Téchiné films of the Eighties and Nineties. The themes don't cohere and the action seems artificial.

What's wrong to begin with, is Venice, the setting, which requires people who alternately speak French and Italian, but don't seem particularly wedded to the locale. Though it's nice that this Téchiné Venice stays away from tourist traps and is not a cliché, it's a pity that it is not also in some way more atmospheric, mysterious, magical, or even ugly. And no amount of motorboats or instructions on tailing somebody along the canals can change that.

Venice may have a lot of real estate agents, but a French one, called Judith (Carole Bouquet), is a stretch. Likewise her being approached by a French mystery story writer, Francis (André Dussollier) who has come to write a book. This was not the setting of the novel (which was the Basque coast), and feels like Woody Allen coming to a new location to liven up his filmmaking routine. Dussollier takes a house out on Sant'Erasmo island, on condition that Judith moves in with him. That's even more of a stretch; the suggestion gives her a nosebleed. But a year and a half later they are married and living there together. Only it turns out Francis is happy now, and when he's happy he can't write. So: writer's block. Francis' daughter Alice (Thierry), an aspiring actress who's married with a child, comes to visit, and then disappears. Francis engages a semi-retired female detective, Anna Maria (Asti), an old flame of Judith's, it seems, who goes off to Paris, to trail Alice. She turns out to be perfectly happy, if irresponsible, having an affair with a shady young Venetian, Alvise (Andrea Pergolesi), the son of an impoverished countess (Sandra Toffolatti). Alvise is a small time drug dealer, as, it turns out, is Anna Maria's son Jérémie (Mauro Conte; his father was French, you see), but Alvise is an "aristo," which Jérémie definitely isn't.

Francis now becomes suspicious that Judith is having an affair and hires Jérémie, just back from jail on drug charges, to follow her. Jérémie doesn't want to and isn't trained to but can't say no because he needs the money. Judith is soon onto Jérémie. They connect and have a brief affair. But Jérémie is also depressive, and, for obscure reasons (homosexual panic?), a gay basher. Despite the moment on the grass with Judith, he does not want sex with men or women, and even dislikes touching people. Francis for a while becomes involved with Jérémie and helps, even saves him. This might be the most important moment of the film, but it happens and is over a little too quickly.

The blocked Francis is always spying on and examining things, looking through binoculars, a magnifying glass, taking photos of everything, like a tourist; he says it helps him in his writing (what writing?). He's trying to get to the bottom of something, evidently, but there's no there there. And there's something pretty nasty that happens with a dog. Anna Maria, an alcoholic and chain smoker, returns to Venice, diagnosed in Paris as terminally ill.

Working with screenwriter Mehdi Ben Attia, who collaborated on Far, Téchiné has modified the novel's first-person narration to present events from multiple viewpoints as in The Witnesses and Changing Times. This definitely makes the film more Téchiné-like, but the tangled strands don't cohere as they might. This could be for several reasons: the corny writer-in-love-and-unable-to-write theme; Francis' inexplicable jealousy; the fact that the two young Italian men Jérémie and Alvise, are shadowy as well as shady figures whose torments or delights never seem to matter. It's hard to think of any really crucial moment, and the pivotal relationship between Francis and Judith, which is arbitrarily set up and keeps being interrupted, lacks emotional resonance. The turning point is the novel Francis writes when his writing block lifts. Due to his jealousy he and Judith have been estranged, but when the book is done, Francis goes to her and she seems welcoming. This is not an emotional shift that feels convincing.

It's nice that this film has at the center a romance of older people. Judith is well into her fifties and Francis well into his sixties. But his sudden, offhand proposal and later marriage and subsequent jealousy and estrangement, followed by reunion after a book's done, all seem like literary gimmicks. The plot line of Unforgivable doesn't, finally, convince.

And in this context Carole Bouquet and André Dussollier, consummate pros though they may be, turn out to be a chilly combination. One longs for Catherine Deneuve, or the great cast Téćhiné assembled for The Witnesses, or Magimel or Binoche, or Amalric, or Auteuil, or the young hotties in Wild Reeds, Élodie Bouchez, Gaël Morel, Stéphane Rideau -- all those wonderful characters, interesting actors, people we could care about.

At his best Téchiné has woven complex plots whose interrelations one deeply pondered and wanted to understand, as in Wild Reeds or Les Voleurs, or explored an individual story that seemed to matter, as in I Don't Kiss, or followed multiple stories that are part of the same important historical moment, as in The Witnesses. Here it is difficult to see what the different story lines have to do with each other or why they matter. There's a Téchiné feel, but not a Téchiné importance. And the reason all this ultimately disappoints so much is that Téchiné has, in the past, made films that really did matter. But this can't be totally dismissed because Téchiné's misfires provide worthwhile commentary on his successes.

André Téchiné's Inpardonnables debuted at Cannes and opened in Paris August 17, 2011, receiving not very enthusiastic reviews (Allociné 2.6). Critics saw the film as long, repetitious, and running breathlessly along too many narrative paths (I'm paraphrasing Cahiers). It has been picked up for US distribution by Strand Releasing. The film is part of the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema March 1-11, 2012 (a joint enterprise of UniFrance and the Film Society of Lincoln Center), slated for the following screenings:

*Wed., March 7, 2012, 6:30pm – IFC; *Fri., March 9, 8:45pm – WRT

*In person: Carole Bouquet

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-25-2012 at 07:50 AM.

-

Alain Cavalier: Pater (2011)

ALAIN CAVALIER: PATER (2011)

ALAIN CAVALIER AND VINCENT LINDON IN PATER

Politics is a game at which we all lose

Cavalier is something of a French provocateur (if a discreet one: but his Le Filmeur annoyed and won a special prize at Un Certain Regard at Cannes 2005) and his Pater was deemed one of the most surprising French entries at last year's Cannes Festival. It's political; it's conceptual. It's witty; for some it's provocative, for others terminally annoying. It's seen by some French observers as a reply to Xavier Durringer's film The Conquest (La Conquête), a French Masterpiece Theater-like rendering of the story of Sarkozy's rise to power. Or it might be a more whimsical version of Pierre Schoeller's L'Exercise de l'État, a fairly realistic and suitably intense film focused on the travails of a new and overtaxed French government minister.

For a year the two were filmed: the filmmaker and the actor; the President and his Prime Minister; Alain Cavalier and Vincent Lindon. In each of these three roles, personal, professional, and metaphorical, the two men interact and improvise on camera in a fiction they invent together. This is Pater. Cavalier doesn't enter like Durringer or Schoeller into the elaborate make-believe of a pseudo-historical contemporary film. Alain Cavalier and his partner Vincent Lindon take on a different game -- one that's more childish and yet both more serious and funnier. Let's play, Cavalier proposes, that I'm President of the Republic and that I name you my Prime Minister.

They take on two topics: the span between minimum and maximum salaries in a company, and electoral politics. Conversations go back and forth. And, by the way, all this takes place at a nice country house, in the study, dining room, and kitchen. When the film begins, Cavalier is spooning out truffles and other delicacies, including tuna, from jars to plates. It's a picnic, and a sybaritic one! There are others who gather around. The team to make a film doubles nicely for the assistants and security people surrounding heads of state. There is some talk about security, but Lindon soliloquizes that Cavalier's fuss over bullet-proof glass at the new residence is really just a way of showing him, Lindon, that he's going to be displeased with him, his Prime Minister. They also talk about ties to wear, and suits, and visit Lindon's museum-like dressing room.

Electoral politics comes later, and it will turn out that Cavalier apparently has lost, before he has even served, and has to let Lindon go. Or run again. And for the election results are substituted a set of 100 euros worth of lottery cards. Cavalier, that is, the President, says he lost because he lacked the energy to go to enough cities. In other words, in shorthand, political campaigning, from the study.

For salary discrepancies, the President favors a factor of 1 to 12. The highest paid cannot make more than twelve times the salary of the lowest paid. The Prime Minister favors a factor of 1 to 10. The President concludes that the head of a corporation can make as much as, and no more than, the President of the Republic. This debate goes back and forth (sometimes with others present) and stands for the highest discussions of policy in a government.

At one point Prime Minister Lindon appears at the Presidency of the Republic and is shown a compromising photo of his political adversary. Should he use it or not? He analyzes the ethics of the situation, if he does, or if he doesn't. Again: a game, and a set of strict rules and consequences. Which you cannot escape, and which you cannot, strictly speaking, win.

In the film, private area and public debate merge. While communication is the law in ministerial cabinets, Pater reminds us that politics is both intimacy and conviction. And asks simple questions: What is the relationship between two politicians? And between a director and actor? And between two friends? Pater's constant deliberate (and natural) confusion of roles makes it challenging and amusing to watch -- although, for those who like a clear set of rules, it may be simply frustrating and confusing. And they should go and watch The Conquest or L'Exercise de l'État, which are worth watching, but do not provide the kind of intellectual satisfaction Cavalier offers.

It's difficult to convey a sense of Pater without seeing Alain Cavalier and Vincent Lindon. And there are moments when they tell very personal things about themselves: Cavalier's lack of familiarity with cell phones and computers; Lindon's quarrel with his landlord, whose inherited wealth and complacent favoring of power infuriate him. Cavalier's mild, distinguished appearance, snowy white hair, dark but unpretentious suits; Lindon's tics, his unruly hair, his "terrifyingly sympathetic" presence, his robust physique, the intensity and surprising clarity and elegance of his speech. The accomplishment of this film is the way it conveys the two men so vividly simply as men before the camera, without destroying the illusion or illusions that are created of heads of state and politics. It's a brilliant touch the way a film crew stands in for the entourage of heads of state; the way the making of a film thus becomes the making of politics.

If you want to understand the Alain Cavalier of Pater, imagine the Lars von Trier of The Boss of It All or The Five Obstructions in a good suit eating potted truffles. Combining him with Vincent Lindon is like mixing the most theoretical and cooly provocative of filmmakers with the most soulful and morally responsible of actors. Pater was seen as one of the most bizarre of films at Cannes and also received nine nominations and a 17-minute standing ovation and this ovation was seconded by the Paris critics when the film opened there in June 2011.

The French critics loveed this film but I warn you, it is more French and more political than an American audience can easily handle. The Variety critic described it as, "The epitome of an in-joke, best appreciated by director Alain Cavalier and his slender cast. " But Le Nouvel Observateur wrote - brilliantly I think -- that "Pater is akin to a class in film taught by a master who pretends to believe you know as much as he, lets you play with the illusion that in his place you'd do as well; thus you feel the film is as much yours as his, as theirs." In other words, Cavalier makes it look very simple what he does, but what is behind the film is shrewd and ingenious. Variety saw it as sloppy and wrote a hasty, dismissive review. Tastes across the pond do radically differ quite often, but this is, clearly, not mainstream stuff and the French public was not as enthusiastic as the press.

Debuted in competition at Cannes, 2011, Pater/Our Father opened in Paris June 22, 2011, with rave reviews (Allociné 4.3) from all the best sources. It is included in the March 1-11, 2012 joint UniFrance-Film Society of Lincoln Center series, Rendez-Vous with French Cinema, and was screened for the press for this review. Public screenings will be four times at three locations: the Walter Reade Theater, IFC Center, and BAMcinematek in Brooklyn:

Fri., March 2, 3:45pm – WRT; *Fri., March 2, 9:15pm – IFC; *Sat., March 3, 6:30pm – BAM; *Sun., March 4, 3:30pm - WRT

*In person: Vincent Lindon

When he made Pater, as he tells Cavalier on camera, Lindon was working in another film: Moon Child, or La Permission de minuit, about a boy with XP, a genetic disorder. This film is also included in the Rendez-Vous.

(Parts of this review are adapted from a Cannes posting about the film on Allociné entitled, "Cannes 2011: We have seen Pater!".

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-27-2012 at 09:09 PM.

-

Nicolas Klotz: Low Life (2012)

NICOLAS KLOTZ: LOW LIFE (2012)

CAMILLE RUTHERFORD AND LUC CHESSEL IN LOW LIFE

Moody romantics and doomed illegals in Lyons

Nicolas Klotz and and his partner and co-writer Elizabeth Perceval's previous film Heartbeat Detecter/La question humaine (2007; Rendez-Vous 2008) featured Mathieu Amalric and Michael Lonsdale as an investigator and the CEO of a sinister corporation with a hidden Nazi past. It was a complex and interesting film, enjoyably mysterious, finally disturbing and powerful. Their new film, Low Life, with its earnest, good looking young people, is charming and fun; surely one isn't supposed to take its broody romantics seriously at the beginning? The film seeks to focus on the sufferings of illegal residents in France. But it remains primarily a pretty and artificial film, and its attractive poses of brooding romanticism tend to overwhelm its sociopolitical focus.

Low Life wavors somewhat confusingly between bourgeois would-be revolutionaries and illegal foreigners in Lyon, with its Afghan poet in love with a local girl and its scattering of young Africans who attempt to put curses on their expulsion documents and their bureaucratic enemies, a device that backfires. The girl, Carmen Alvarez (Camille Rutherford) switches from the immature poseur Charles (Luc Chessel), who at first seems as though he will be the main, if ironic, character, to the foreign poet, Hussein (Arash Naimian), whom she meets when students clash with police in an effort to save Africans in a squat. It would be so much simpler, Hussain says, if he were Egyptian, but he's Afghan -- and a scrawny, by all indications brilliant young student of French literature with thick lips and and a nice smile. He and Carmen soon become inseparable, and Charles cedes the field, though remaining in reserve.

With its doomed, proto-revolutionary poet-lovers (some of whom wish their street demos would be livened up by bombs), this new Klotz film is rather like a 21st-century version of Philippe Garrel's Regular Lovers. There is the same darkly happy dance scene (and lengthy partying), the same doomed poet lover, the same scenes of street fighting and moody, poetic youths. In fact an earlier poster gives the title as Les amants, The Lovers, suggesting a direct influence, but a different mixture.

Indeed too much of a mixture. This film isn't rooted like Garrel's is a revolutionary historical moment (1968). Its narrative threads do not cohere as well as Garrel's, or stand up to the level of Klotz's previous film. I would have been happy with the pretentious and naive young French people -- with the juvenile, preposterous, but irresistible Charles, spouting poetic revolutionary phrases and declaring undying love in good French accents while showing off their long hair and good cheekbones. But once the bourgeois dropout kids come into contact with the young illegals their posturing begins to seem irrelevant. Unfortunately they never leave the scene. (Charles may also be a reference to Bresson's doomed protagonist in Le diable probablement.)

The Afghan poet lover Hussein has had a document issued ordering him to leave the country and after three years has been denied asylum. He and Carmen remain together and he goes into hiding in the house. Together at times he and Carmen go into a torpid semi-narcoleptic state together, a condition they call "low life."

Charles still comes and goes, having given up all projects other than Carmen, contemptuous of his father but willing to share a good bottle with him when opportunity arises. Charles's pretentious and naive romanticism remains absurd but somehow charming, as when he lies in a pond as if to drown himself, but is only posing. Apparently to console Charles for being dumped by Carmen, there is a passage of flamenco singing and dancing. There was something like this in Heartbeat Detector too (in that case Portuguese fados) but there it heightens the tension. Here it just seems a bit off-key. The Africans paint their faces and enact a voodoo rite, but while they show the desperation of illegals at another level, there's a dangerous feeling that they are being exploited for visual effect.

Klotz-Perceval do not weld together separate elements the way they did in Heartbeat Detector, where everything is unified by the interaction between contemporary malaise and the corporation's sordid emerging Nazi past. The only thing that holds together Low Life is youthful romanticism and a strong visual sense. No matter whom we're looking at the young people all look good, and some of the shots of interiors by Hélène Louvart using only a Canon 1D DSLR look quite handsome. There is also a good sound track of studio and mixed music and voice by Ulysse Klotz and Romain Turzi. The middle-aged Klotz and Perceval capture the naivety and pretension of the young almost too vividly. It would be fine if all this were tongue-in-cheek, except that the students' early-on revolutionary clash with the police seems only make-believe.

It is hard to link jingoistic French cops with Nazis, as Carmen tries to do, and hard to make the theme of this film as powerful as the theme of Klotz's last one, especially when some of his moony youths are so silly at times. Given the harsh theme of the undocumented, there is too much posing and not enough reality.

Low Life debuted at Locarno, and also was shown at Toronto in 2011. It goes into theatrical release in France April 4, 2012. It is also a part of the March 1-11, 2012 joint UniFrance and Film Society of Lincoln Center series Rendez-Vous with French Cinema, in connection with which it was screened for this review. Three public screenings will be given during the Rendez-Vous at the Walter Reade Theater and the IFC Center:

*Sun., March 4, 8:30pm – WRT; *Mon., March 5, 10:05pm – IFC; Wed., March 7, 2pm - WRT

*In person: Nicolas Klotz

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-10-2015 at 11:22 PM.

-

Cyril Mennegun: Louise Wimmer (2011)

CYRIL MENNEGUN: LOUISE WIMMER (2011)

CORINE MASIERO IN LOUISE WIMMER

Long slow round of days

Cyril Mennegun's 80-minute writer-director debut feature Louise Wimmer is an "unapologetic work of social realism" focused on the daily life of a hotel chambermaid and housecleaner (Corinne Masiero) now approaching fifty who has wound up living out of her car. Her whole life is devoted to trying to put together the money to get an apartment, and start anew. The film is composed of many very short scenes that put together a cumulative picture of how she spends her days, how her existence is continually being eaten away despite her patient and persistent efforts. No compelling, precipitous narrative here à la Dardennes. The emphasis is on a convincing performance by Masiero and an authentic feel to the settings, people, and action. And the sequence of scenes provides a kind of gradual revelation of hints about how Louise got here and what her story is and where it is going. Within the limited range where Mennegun chooses to work, his accomplishment is impeccable. And this is by no means a simplistically downbeat miserablist piece of work. Louise has good things in her life and she is not giving up.

This was screened as part of the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema (a March 1-11, 2012 joint presentation of UniFrance and The Film Society of Lincoln Center). The film will be shown to the public at the IFC Center and the Walter Reade Theater:

Sat., March 3, 3pm – IFC; Mon., March 5, 2pm – WRT; Tues., March 6, 6:15pm - WRT

-

Olivier Marchal: A Gang Story (2011)

OLIVIER MARCHAL: A GANG STORY (2011)

TCHÉKY KARYO AND GÉRARD LANVIN INA GANG STORY

Vicissitudes of the gangster code

There are still a few more films in the 2012 Rendez-Vous series not included in the press screenings. This one, which swings back and forth between the Seventies and more recent times, is a bracingly violent and complicated gangster movie based on a memoir. Olivier Marchal, whose sixth feature this is, is a former policeman. Within its limits this is extremely well done. The French make their own kind of crime movies, and if Guillaume Canet's Tell No One and Jacque Audiard's The Prophet are any example, they do it better than Hollywood nowadays. This one has touches from The Godfather -- it's trendy opening titles don't conceal the fact that it owes debts to the past -- but it's rooted in Mediterranean omertà. It fundamentally concerns two childhood pals, bound by a gypsy bond of masculine friendship. They're Momon Vidal and Serge Suttel (played as fifty-somethings respectively by Gérard Lanvin and Tshéky Karyo) who are jailed together for their first crime, stealing a case of cherries, when in their teens and then get put away later for longer stretches due to an informer who is never identified. Starting out, they work for gangsters around Lyons -- the French title of the film is Les Lyonnais -- and then risk the anger of the big boys to start a gang of their own.

In the present, less faded-out scenes, Serge has been caught after many crimes and much hiding and Momon is called upon to get him out, but he has a younger, more unscrupulous crew do the job, a choice he later regrets. All this is mixed with flashbacks to the history of Serge and Momon's friendship and joint lives of crime, so both tales slowly advance simultaneously. Both are very violent. Marchal has a way with cars and automatic weapons of any period and the violent scenes are beautifully if sometimes shockingly or numbingly staged. Given its basic theme of gang loyalty, the film is needlessly complicated. If it were a little simpler and less elaborate technically and had less loud racy music it might have more lasting emotion. But it's still a good watch for fans of French gangster movies and tells an agreeably tangled tale of criminal loyalty and betrayals.

The Variety reviewer Boyd von Hoeij points out that the film's violent crime scenes which he (a little unfairly) calls "mayhem-chic montage sequences" are all set in the past, with the exception of the jail break for Serge with Momon absent. Hoeij feels that since the "more contemplative moments" belong to Gérard Lanvin (whose gnarly wrecked good looks provide a glamorous screen to flash back disillusion) and the film contains separate narratives that don't quite "coalesce." It looks as if Marchal had a lot of fun shooting the Seventies young-men gangster sequences and makes them go on too long, or not long enough since they have too little dialogue or distinct plot.

Les Lyonnais is very conventional but it has the power to entertain. Banking on this working in American art houses, Harvey Weinstein has thought fit to pick it up and release it in the US (at a date not yet announced). It got a mixed reception from French critics when it opened in Paris November 30, 2011, with an Allociné rating of 2.8, showing a few enthusiastic reviews but a number of ones with reservations. It's been compared to the much more elaborate gangster biopic Mesrine , but that fared much better with critics. Its narratives of different periods were more fully developed, and rather than focusing on nostalgia for a dying gangster code, it concentrated on rich historical detail, though still offering plenty of violence and excitement. But that was two features: Marchal's film comes in a tidy 75-minute package.

Presented as a part of the UniFrance and Film Society of Lincoln Center March 1-11, 2012 Rendez-Vous with French Cinema. Scheduled at IFC Center and Walter Reade Theater for:

Sat., March 3, 4:45pm – IFC; Thurs., March 8, 8:45pm – WRT; Fri., March 9, 4pm - WRT

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-02-2017 at 12:18 PM.

-

The Best and Worst of the Rendez-Vous

THE BEST AND WORST OF THE RENDEZ-VOUS, 2012

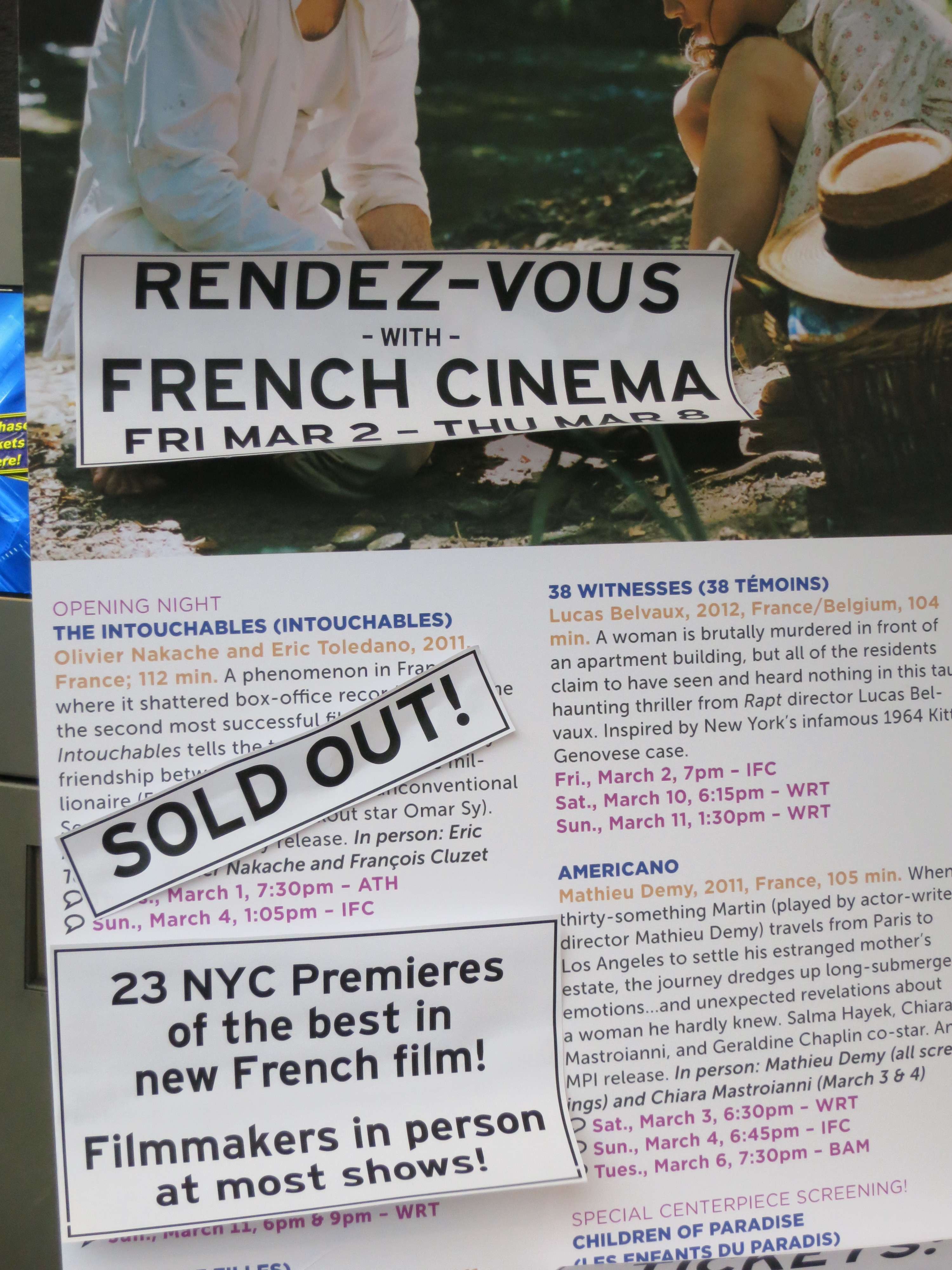

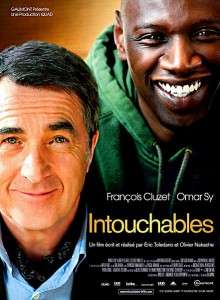

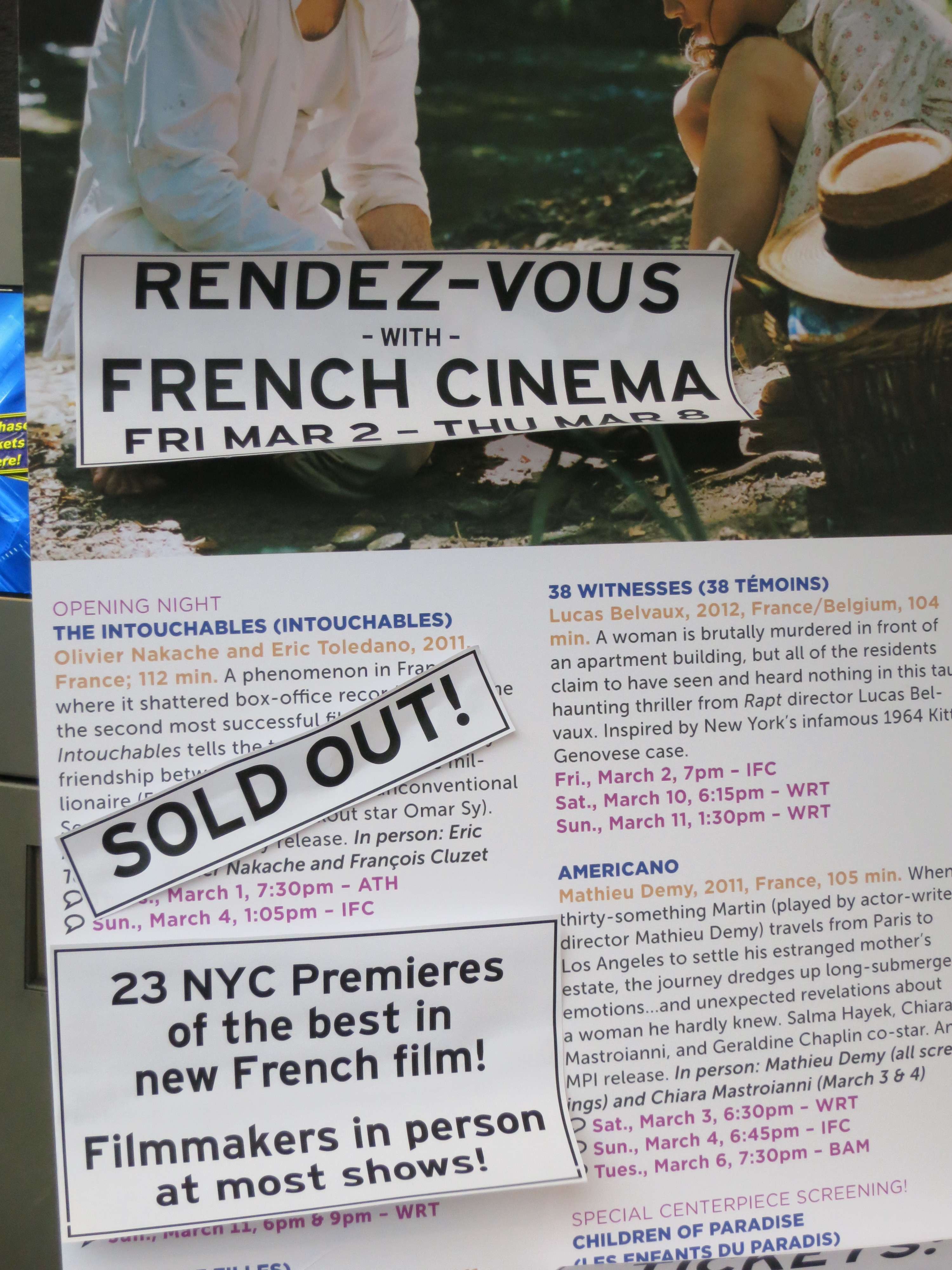

Opening night film : UNTOUCHABLE by Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano. March 1.a

A true story of two men who should never have met - a quadriplegic aristocrat who was injured in a paragliding accident and a young man from the projects. Jay Weissberg of Variety describes this as "cringe-worthy" for its "Uncle Tom racism." More likely it's just cliched and saccharine, which UniFrance and the Rendez-Vous unfortunately have a weakness for, and would provide on opening night. It has been box office gold in Franc. Allociné rating 3.7.

NOT SHOWN TO US

OPENING NIGHT FILM

Closing night film : DELICACY by Stéphane and David Foenkino. March 11.

A French woman mourning over the death of her husband three years prior is courted by a Swedish co-worker. Audrey Tatous: need I say more? More clichéd sugar, evidently less well executed, since the Allociné rating was a measly 2.5.

NOT LIKED

CLOSING NIGHT FILM

SUMMING UP THE RENDEZ-VOUS WITH FRENCH CINEMA OF 2012. ("Best and worst" may be a misnomer.)

The Rendez-Vous is a representative series that shows the quality and variety of French filmmaking. It would be nice but unusual if it included the best French film of the year but also unlikely to include the worst. The opening and closing films are usually the series' most glitzily mainstream. Much else is more sophisticated.

A favorite of mine was first-time director Fred Louf's 18 Years Old and Rising, a witty and fun period coming-of-ager satirizing bourgeois fat-cats and starring Pierre Niney, the youngest member of the Comédie Française, who is fabulously nimble and funny. This film is something Americans don't know very well how to do: smart, sexy political comedy (compare The Names of Love).

I was struck by the warmth and fluency of Robert Guédiguian's left-oriented family story that talks about the working class and its responsibility to the have-nots, The Snows of Kilimanjaro. This is the first time I've seen him fully on his own turf and it was impressive. Very enjoyable to see his regular team of actors working so well together.

I must admit to thoroughly enjoying Daniel Auteuil's remake of Pagnol's 1940 The Well-Digger's Daughter. It's such a humane and satisfying world, and Auteuil's chops are certainly up, in a directorial debut he wrote and starred in. The French critics were not very excited. They've been there too many times before. For me it was satisfying to find Auteuil in a Pagnol movie that didn't bore me. All this stuff is tremendously retro: but why not go back and look at it?

A surprise and a place where I seemed on another wavelength from the rest of the mostly American press audience at the Rendez-Vous IFC screening was my enjoyment of Alain Cavalier's conceptual piece about French politics, Pater, which may succeed better through the sympathetic presence of Vincent Lindon. His warmth (not to mention his tremendous authority and credibility as an actor) balances out the dry rather smug manner of Monsieur Cavalier, who however is to thank for the structure and many of the ideas.

The press screenings put on by Lincoln Center for this series didn't include everything this year and the most notable omission was Untouchable, which is the opening night film and a huge blockbuster in France. In his NYTimes' intro piece for this year's Rendez-Vous, Stephen Holden calls this "a crass escapist comedy that feels like a Gallic throwback to an ’80s Eddie Murphy movie." But it would be good to see what's box office gold in France now. The Artist received six Césars the other day, echoing the Oscars and other prior American and English awards for this safe, nostalgic, and French-free film, but they gave the Best Actor César to Omar Sy, the black star of Untouchable, rewarding popularity. Untouchable has been picked up by Harvey Weinstein (who scored with The King's Speech and The Artist , and for him perhaps this is another promising import). Americans will get to see Untouchable in theaters starting May 25th.

Holden joined the early American band wagon condemning Untouchable. He is right to harp on this inclusion, to make clear the Rendez-Vous is not by any means an elite cream-of-the-crop festival like the Lincoln Center's fall New York Film Festival. Holden particularly liked Benoît Jacquot's off-center film about Marie Antoinette, Farewell, My Queen, which indeed is different and nice, and Léa Seydoux seductive and offbeat, but the film not so very memorable, I think. Holden thought the teen pregnancy piece, 17 Girls "feels really contemporary." Yes, feels. But it'd be better if it were not inaccurate and so light. Jean-François Laguionie’s The Painting animation is indeed "witty" and rather touching; I liked it. I liked almost everything! The world is full of nice animations. Holden expressed some "disappointments." Yes, one cann find those, I suppose (but I said I liked almost everything). He was disappointed in the Audry Tatou vehicle Delicacy. Yes, it's a kitsch pseudo-American mess; but why was he expecting anything? (It is the closing night film -- often a warning). Holden was disappointed in Belvaux's 28 Witnesses -- because it's cold and gray and Belvaux made the riveting Rapt. Yes, we all were.

Frankly a low point was Mathieu Demy's clumsy Americano, which the French press gave a free ride to (their picture of America is different from ours). Amalric's modern dress Corneille The Last Screening was a bit disappointing, too hard to follow and -- dare one say it? -- unnecessary. I wanted to love Low Life, but it seems self-indulgent.

Others films that were good if not extraordinary are the grim but true Guilty (whose star Phiippe Torreton got a César nomination); the film about a special friendship, Moon Child; the solid policier, Paris by Night (with Roschdy Zem); the slightly pale (but about a good topic) Free Men, with Tahar Rahim (who I hope can live up to the extraordinary beginning Audiard gave him in The Prophet). Headwinds, Magimel directed by Lespert, was creditable.

But there don't seem to have been as much in the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema to set my heart on fire this year. I don't think there was anything as exciting as Rapt or In the Beginning in 2010, 35 Shots of Rum, Mesrine (both parts) or Séraphine in 2009; Lovesongs, Heartbeat Detector or All Is Forgiven in 2008; Flanders or La Vie en Rose or The Singer or Tell No One in 2007; The Little Lieutenant in 2006.

It says something that one of the most striking new French films I've seen in the past few weeks was Mathieu Kassovitz's Rebellion/L'ordre et la morale. It is very accomplished technically and approaches a complex modern subject on many levels. And it wasn't in the Rendez-Vous series at all. It was in Film Comment Selects, which also included a new film by Chantal Ackerman (which I missed). Likewise Pierre Schöller's exciting political film The Minister, a powerful film -- not in the Rendez-Vous but coming up in New Directors/New Films, the next series at Lincoln Center (jointly run with MoMA).

New Directors/New Films, the Lincoln Center film series coming up after the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema, will include several French films: Djinn Carrénard's Donoma, Pierre Schoeller's The Minister/L'Exercise de l'État (which I've already reviewed), Roschdy Zem's Omar Killed Me, and Antoine Delesvaux's animation from Joanne Sfar, The Rabbi's Cat. New Directors/New Films 41 runs from March 21-April 1, 2012, but I will be commenting on the films earlier during the Mar. 5-21 press screening period.

Note that I watched some of the eclectic, unclassifiable Feb. 17-Mar. 1, 2012 Film Comment Selects series: Alexandr Sokurov's Faust, James Franco's My Own Private River (all except the Franco part), Hirakazu Koreeda's I Wish, and the aforementioned Kassevitz's Rebellion.

The 2012 Rendez-Vous with French Cinema begins at IFC Center, NYC March 2.

-

Vincent Garenq: Guilty (2011)--RV

VINCENT GARENQ: GUILTY (2011)--R-V

PHILIPPE TORRETON IN GUILTY

Intense victim-based docudrama of a judicial nightmare

The first sixteen minutes of this film, Guilty/Presumé coupable ("Presumed Guilty"), alone are devastating. It is hard for anything afterward to live up to them. Philippe Torreton is nominated for the César for Best Actor for his performance as Alain Marécaux, a hard-working bailiff, who with his wife and a dozen other people was the victim in 2001 of one of the worst judicial errors in modern France. They were accused completely falsely of being members of a ring of pedophiles guilty of horrific crimes. The judicial and police system is singularly brutal here. What we see in thos opening minutes is Alain and his family having their house invaded in the early morning, being rapidly and brutally taken away by smirking cops, handcuffed, interrogated, threatened, and treated as a sick maniac. It turns out this is the now notorious Outreau affair, and 17 were accused, of whom only four, who were those who accued the others, were ever proven guilty. A overview of the events of the case will be found on French Wikipedia. It took five years for this to be concluded, and some, including Marécaux, spent most of this time in prison. He lost everything, including his job, his family, and his reputation. He attempted suicide several times and went on a hunger strike.

Unfortunately this precipitous opening is a hint of the whole approach, which is too direct and humorless. A bit of detachment is needed to make anything more than mere pseudo-documentary out of the story. The constant in-your-face hand-held focus on Torreton emphasizes his anguish and suffering and the injustice of the whole affair, but limits the picture given of what is a complex social, political, and legal matter. We get that Maréceaux knew nothing about all this and was innocent and that this was a nightmare for him. But how did all this come about? What are the forces behind the miscarriage of justice? What happened to the principle of presumed innocence? Who stands to gain? Choosing to focus unwaveringly on the judicial victim proved to be a tactical error.

We are left to draw our own conclusions. Some of them are obvious. The public loses its perspective completely in the case of sex crimes, particularly of a pedophile nature. False allegations of pedophile rings also came up repeatedly in the US as well. These may be the witch trials of modern times. But Garenq's film sheds little light on this process. The kind of ambiguity we find in Capturing the Friedman's is missing, and instead of being troubled and stimulated, the viewer feels bludgeoned over the head repeatedly for 102 minutes. Material that should be the cause of reflection is not. Due to the drawn-out nature of the judicial nightmare, datelines might have helped. What is made clear in the final court proceedings is that the young investigating judge (juge d'instruction) responsible for all this suffering does get exposed, even though his superiors defend him. Years later Marécaux is able to resume his duties as bailiff, finally exonerated.

In order to manifest his character's physical and psychological suffering in prison, Torreton, an experienced stage actor with many roles for the Comédie Française and other companies to his credit, lost over fifty pounds. His performance is a dedicated one otherwise as well, and it is for this that one watches Guilty. Torreton excels at showing the humiliation, anger, depression and gradual degeneration of this humble servant of the law as he suffers the effect of his unjust incarceration. We must bear in mind that in this he stands for the many, because there were 17 accused.

What this account shows is that as in American cases, children are coerced by suggestive questions to make false statements and a collection of rumors and accusations builds up. The involvement of Maréch aux's own son recalls the Friedman case.

Guilty opened in Paris September 7, 2011 and received generally favorable reviews from the more mainstream publications. Others expressed the same reservations I have, but all note Torreton's dedicated performance. It was also shown at Toronto, London, and Montreal. The film is part of the joint Film Society of Lincoln Center-UniFrance Rendez-Vous with French Cinema of March 1-11, 2012, and public screenings are as follows:

Mon., March 5, 6:15pm – WRT; Tues., March 6, 1:30pm – WRT; Thurs., March 8, 10:25pm – IFC

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks