-

Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011)

NURI BILGE CEYLAN: ONCE UPON A TIME IN ANATOLIA (2011)

A long and winding road to an autopsy

I can do no better than Mike D'Angelo's appreciative but unconvinced report on the Turkish direictor Nuri Bilge Ceylan's new film, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia. Here's what D'Angelo posted for the AV Club from Cannes last May: "The latter is an intelligent, meticulous, incredibly beautiful movie that’s offered plenty of food for thought since I saw it, but that I found downright torturous to actually sit through. Mostly, that’s because Ceylan is playing a deliberate, formalist game of keep-away, introducing what looks on the surface like an exciting narrative—the film opens at night, with a bunch of cops and other officials toting two criminals around gorgeously barren landscapes in search of a corpse—only to slow the 'action' to a crawl (it takes 90 minutes of this two-and-a-half hour movie just for them to find the body) and focus our attention on bureaucratic trivia and raw bits of the characters’ psyches. Ceylan knows precisely what he’s doing—a lengthy shot of an apple tumbling downhill into a stream, merely to come to rest beside other rotted apples, all but chides us for seeking direct answers—and he uses car headlights the way Kubrick used candles in Barry Lyndon, but I still had enormous trouble staying alert amidst the endless trudging and sniping and sharing of seemingly random anecdotes."

He doesn't trust his reaction, pleading that he saw it late at night (he tends to have five-film days at festivals) and thinks Cannes' high regard (this co-won the Grand Prize with the Dardennes' estimable and consistent The Kid with the Bike) means he "might want to take a second look in future."

When he's on point as he is here, D'Angelo is vivid and accurate, and I can only agree that the wide aspect photography, with its tinges of yellow and digital luminosity, is gorgeous in the early segments as the three cars trail through the stark flat hills, so much so that simply watching the images is a pleasure in itself. The sudden alternating, contrasting closeups of men packed into a car, an aggressive police officer who's tried to stop smoking, a man they call "Arab" who does the driving, a sly, quiet doctor (who emerges as the film's favorite character) and a well-dressed prosecutor with a pock-marked face, with the main prisoner in the middle in the back, and the endless trivial conversation -- all this seems just an ironic joke to contrast with the beautiful landscape outside, which is heightened by thunder and lightning and a threat of heavy rain (which never comes).

Then there is the starting and stopping, the prisoner, angular and gypsy-like, abused by the police officer and his cohorts, repeatedly saying no, this isn't the place. They are trying to find where he buried a man he killed.

After a while when it's very late but still dark, they all stop, three cars, at a small village, where the local mukhtar (mayor) gives them dinner, and they are served by his young, beautiful daughter, who brings in a tray of tea with an array of small lamps that remind one even more of Kubrick's use of candles in Barry Lyndon, if you're so inclined. The prisoner, who dines with them, comes up with a confusing revelation. And then they go on and by the time it becomes light, the prisoner finds the burial place and they dig up the corpse of the man he killed, and there's a fuss about the fact that the dead man has been hog-tied, which turns into a mordant joke when they prepare to haul the dead man back with them to their town.

And everyone is exhausted, we too, and finally there is a rather gruesome autopsy, as the doctor peers out a big window and sees the murdered man's widow and her young son, who has a haunting face, wander away over a hill with a crowd of small boys playing below them.

If that floats your boat, rush to see Once Upon a Time in Anatolia. (The Cinema Guild has acquired U.S. distribution rights.) Ceylan has done fine, resonant, wry work in the past, but he goes very much his own stubborn way -- perhaps this time too much so. I would suggest that this, for all its meticulously observed characters and almost real-time examination of a curiously uninteresting and yet in some ways haunting police procedural, is more in the order of an auteurist shaggy dog story than anything I've seen before at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review. Here, as at Cannes for Mike D'Angelo, it was "downright torturous to actually sit through." Since Cannes, it has been in at least eight other festivals, including Toronto. It will be released theatrically in Turkey, Greece, and France in September, October, and November, respectively.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-30-2011 at 07:12 PM.

-

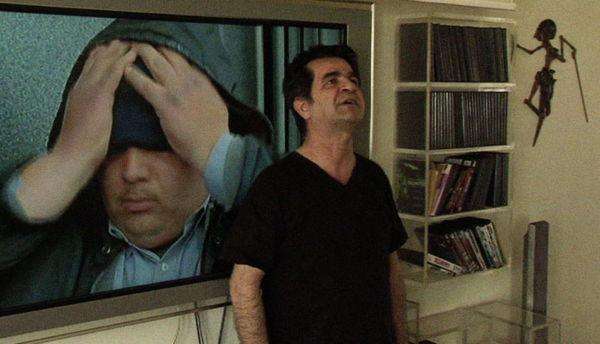

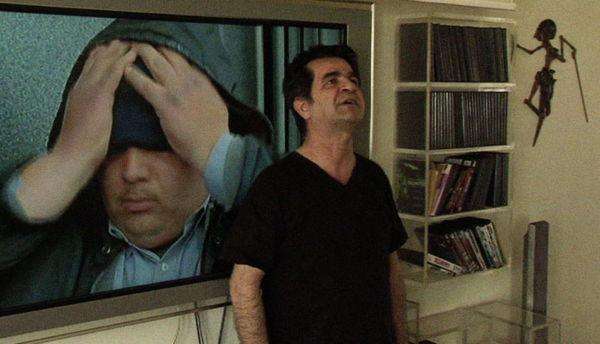

Jaafar Panahi: This Is Not a Film (2011)

JAAFAR PANAHI: THIS IS NOT A FILM (2011)

JAAFAR PANAHI IN THIS IS NOT A FILM

A muzzled artist speaks

It may indeed not be a film. But it is something else: a statement about repression. The celebrated Iranian director Jaafar Panahi (Crimson Gold, Offside) chose this title because he has been prohibited from making films by the Iranian government. This is not a film because if it were, Panahi would be violating the mullahs' orders. Apparently for supporting the protests against the reelection of Ahmadinejad, Panahi was arrested several times in 2010. Late in the year he was put under house arrest and officially prohibited by the Iranian government from plying his trade as a filmmaker for the next 20 years: no directing, no screenwriting, no interviews, no departures from the country. And a prison sentence is pending.

So This Is Not a Film, made by Panahi with help from the documentary filmmaker Mojtaba Mirtahmasb without leaving his apartment and smuggled out of Iran, it is said, on a USB thumb drive hidden in a loaf of bread, is an act of subversion and protest against his repression by the regime, not to mention the general repression of Iranian filmmakers. Nearly every Iranian film today is an overt or veiled criticism of the situation in the country. But This Is Not a Film is raw evidence of the deteriorating current situation in which one of the most prestigious of the country's directors can be silenced for nothing other than giving the nod to in demonstrations in which thousands of other Iranians were involved.

In post-modern art, ideas are exhausted or imagination is dead so the artist must try to make art out of nothing. But Panahi's problem is a more simple one. How do you make a film when you are prohibited from making one?

In This Is Not a Film, whose credits list it as an "effot" by the director rather than a "film" and gives Mirtahmasb as a collaborator but leaves all other staff names blank, things begin simply with Panahi having breakfast at a table and calling Mirtahmasb. The scene could be something by Elia Suleiman, the Palestinian director, whose situation of living under Israeli occupation is similar. In both cases, in the innocuous moment, you feel the walls around the walls.

Panahi asks his colleague to come quickly because he has something for him to do, and not to tell anyone where he's going. A phone message recorded while the empty bedroom is filmed says Panahi's son has set up the camera. This would mean Panahi is not breaking the ban, though he later does carry the camera, after Mirtahmasb leaves, filming a man who says he's filling in for the janitor (is he a government spy? If so he's a good natured one, even an admirer).

Events are somewhat random. First, Panahi talks to his lawyer on the phone. She tells him that it is likely she can get his prison sentence lowered -- to six years. But she thinks the 20-year prohibition from working will stick. He has waited for the response to the appeal for months, and is still waiting, but thinks the result may come at any moment.

Amusement and absurdity come when Panahi waters plants, tries to feed a big pet iguana called Igi, and fends Igi off when the lizard, suddenly friendly as a cat, climbs all over him as he tries to type. Further comedy arrives when a neighbor tries to leave off her little dog, Mickey. It's obvious Mickey and Igi are not going to get on and Panahi sends Mickey away immediately. But the sad heart of This Is Not a Film is Panahi's vivid attempt, as his friend wields the camera, to recreate the first scene of the film he was about to make when he was arrested. He puts tape on the floor to outline the small room of a poor girl whose religious family are barring her from going to the university. Panahi breaks down in the middle of this recitation and demonstration, saying, "If we could tell a film, then why make a film?"

Fascinatingly, Panahi also briefly talks about two of his earlier films, showing clips on a big flatscreen monitor. In the first film a young girl on a bus rips off her cast. She is an actress in a film, but she refuses to participate in the pretense that she is a little girl who got on a bus going the wrong way. The camera catches the filmmakers struggling as she throws off her cast, vehemently protesting, and gets off the bus, refusing to act any more. Using a DVD of Crimson Gold, Panahi shows a scene where the family is rudely treated by the jewelry shop owner and the main character (played by a real-life pizza delivery man) throws back his head and glares heavenward. Panahi says in both these scenes the non-actors took over and did the directing. He had not planned for the shop owner to be so condescending or for the pizza man to be so oddly dramatic.

Using unplanned elements is key even in the most precisely orchestrated films at times. But how much is "vérité" ever "vérité"? How much events like the iguana's antics, the phone calls, a food delivery, or the arrival of the university student subbing for the janitor may be pre-planned or orchestrated by Panahi himself as scenes in the film is uncertain. But for a film about nothing that is not a film, This Is Not a Film manages to be pretty lively. A background of the Dogville-like diagraming of the projected film about the poor would-be student and everything else becomes the sound of explosions, which turns out to be fireworks for Nowruz, Iranian New Year. These explosions are the background for Panahi's conversation with the sustitute janitor. And that conversation develops into the big set piece of the film when Mirtahmasb leaves and Panahi, after using his iPhone to film for quite a while (footage edited into the film), grabs the big HD video camera and gets on the elevator with him riding from floor to floor, gathering garbage.

The student/janitor tells about himself. He is a masters candidate at the Arts University. He works at many jobs. He tries to tell an extended story that keeps getting interrupted as he stops at floors and looks out to see if the tenants have put out their garbage. Eventually the lady from the lower floor appears and tries to foist Mickey on the young janitor. The way the young man walks off through a parking garage into the darkness with fireworks blazing nearby is a curiously moving finale.

It is likely that all this is very well worked out and yet it seems utterly casual. In either case it is a sign that Panahi's skill as a weilder of Iranian neorealist style, now applied to himself, has not diminished. And the aim has been achieved: of giving us a look at a filmmaker whose hands have been tied by an oppressive regime, and who refuses to be silenced.

Jaafar Panahi has been celebrated at international film festivals since his debut feature White Balloon won the Camera d'Or at Cannes in 1995. His The Circle, which is about a woman trapped in a world of Islamist opporssion, won the Golden Lion at Venice in 2000 and many other accolades. Crimson Gold, a sly study of class resentment, won the Un Certain Regard prize, again at Cannes, in 2003. Offside (NYFF 2006) again touches on the role of women in Iranian society, with wry wit and a realism that creeps up on you. It won the Silver Bear at Berlin.

This Is Not a Film (78 min.) debuted at Cannes in May 2011. It has had a theatrical release in France, and will have similar ones in Sweden and Australia and, apparently, the US. It has been shown at other international film festivals, including New York, where it was screened for this review. What decision if any has been meted out on Panahi's appeal to the court we do not know. Many distinguished international figures have protested Panahi's confinement.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-04-2011 at 11:57 PM.

-

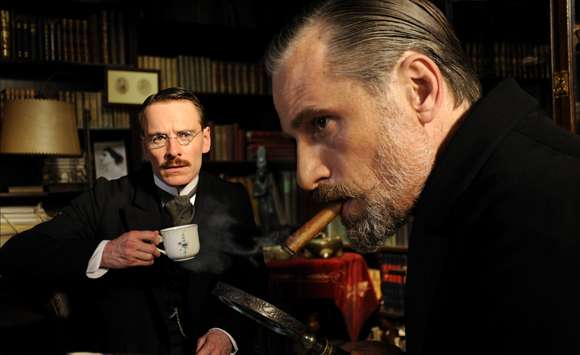

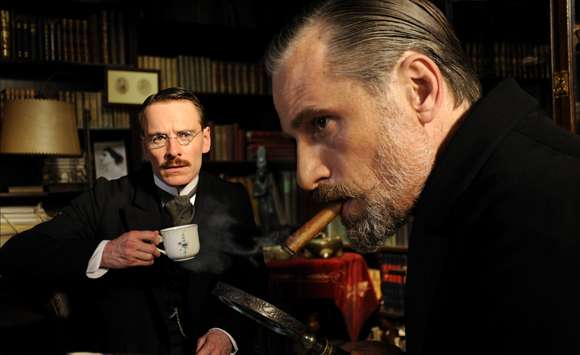

David Cronenberg: A Dangerous Method (2011

DAVID CRONENBERG: A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011)

FASSBENDER AND MORTENSEN IN A DANGEROUS METHOD

A waxen gala

A Dangerous Method is a beautifully made but curiously and depressingly safe film. It tells the true story of a Russian Jewish woman called Sabina Spielrein, at first a patient of Karl Jung, then his lover, who eventually came to be associated with Jung's Viennese colleague and eventual adversary, Sigmund Freud, and later, through the encouragement of both men, became a pioneer in psychotherapy in her own right. The joint connection came to define and crystalilze the fraught relationship between the two leading early figures in psychological theory and psychoanalysis. Christopher Hampton, the playwright and screenwriter, originally developed the script from a book called A Dangerous Method by John Kerr, for a film that didn't get made. Undaunted, the tireless adaptor instead turned it into a play called The Talking Cure that was produced on the London stage, and later he turned that into the screenplay from which Cronenberg made this film starring Michael Fassbender (as a sensitive but slightly too dapper Jung) and Viggo Mortensen (as an almost equally dapper, slightly older, constantly cigar-smoking Freud) and Keira Knightly (as a mugging, twisting, Russian-accent affecting Spielrein). The film is beautiful, elegant, and lifeless. Even the S&M scenes are like postcards of a swiss kitchen.

The lifelessness begins with the screenplay, a handsomely crafted piece of work which seems a little too much like an articulate Brit's Freud and Jung for Dummies. Hampton is great at the well-made play or the filmable adaptation, but boy does he do it by the numbers sometimes. (Dangerous Liaisons was another story.) Everything is clarified and simplified to the point where it contains virtually nothing about psychology that will be news to a basic student. This concerns two of the most exciting intellectual figures of the twentieth century, men whose work changed how we think about sex, emotion, the mind. And yet, here, in this film by a director who has dealt in horror and madness, it has all become so tidy and Germanic that it's like looking at a diagram.

Another problem is the casting. Knightley impresses when she is prim and beautiful. A raging neurotic with huge daddy issues, and Russian Jewish to boot, is way out of her range. Both Mortensen and Fassbender are wild men. Cut them loose and they can give you an edge of macho danger that's first class. The old Cronenberg, or what was left of him in A History of Violence, gave Mortensen room to be a mild mannered man who killed men with sudden precision. Fassbender likewise works well with extremes as he got a chance to do in Inglourious Basterda and the more recent X-Men: First Class, not to mention the ultimate testing he went through as Bobby Sands in Steve McQueen's searing Hunger. If you compare him in Jane Eyre and as the Irish seducer of his girlfriend's young daughter in Andrea Arnold's excellent Fish Tank you can see he can get stiff and remote in period costume, while given something closer to home he can chill you and charm you like nobody else you've ever seen. Even though there are sex scenes, he doesn't even seem to take his pants off for them as Jung. This Freud and Jung look too similar physically and too close in age. Good for Mortensen, who is actually 19 years older than Fassbender, but he looks very much younger. Both men are way more sexy than this. They are on their good behavior. Fassbender has some good moments. But Mortensen seems to be on Valium, delivering every line in the same slow, easy, somnolent pace.

It's hard to pass over the fact that the whole thing is done in English (though Fassbender in real life speaks German), the two men speaking a standardized version and Knightley, her version of a Russian accent (which perhaps fortunately comes and goes). Along with this, the production. It is beautiful. But nothing is allowed to be dark and messy. Freud's office was a huge disappointment. We all know what it looked like, the oriental rugs, the clutter. But the clutter is all swept to one side, lined up along the walls. The filmmakers prefer to shoot their people in brightly lit rooms or outside in very sunny open spaces. Gosh, I mean, wasn't the unconscious a dark and scary place? Weren't archetypes huge and mysterious and powerful? One is overwhelmed by starched white linen here.

Is there any need to point out that we don't get to delve into these men's revolutionary and controversial ideas? The "talking cure" is just that. Jung sits behind the twisty Fraulein Spielrein and asks her questions. That seems to be all that was required to turn her from a raving maniac into an outstanding medical student. Those Russian Jewish girls are quick studies. This is Jung using Freud's methods of psychoanalysis. He never really gets to explore his own ideas, just to listen to Freud calling them quackery that will spoil the new methodology's reputation. We want Freud to be broody and difficult and messed up and brilliant and Jung to be a little wild and visionary and mystical. None of that. Too much starched linen.

It's official now: David Cronenberg has fallen in love with his new respectability as an auteur. The respectability was probably creeping in with Spider, and the mantle was bestowed with A History of Violence and ratified with Eastern Promises. Since Viggo was important in both of these, he doubtless had to be kept on for A Dangerous Method, and the job of playing Freud was open. Where is the "king of venereal horror," the "baron of blood"? The guy who gave us eXistenZ, and before that Videodrome, The Dead Zone, and The Fly? Or the gloriously sicko Dead Ringers, which gave even Japan horror fans the creeps? I personally love the man's Naked Lunch. Burroughs' book is unfilmable, but Cronenberg made something deliriously and hilariously trippy out of it nonetheless. You could hash over many other titles, and some of them may drift further toward art or hack work. But when you look over these, it's hard to see A Dangerous Method as a job for this director.

A Dangerous Method, chosen to be a "gala screening" of the 2011 New York Film Festival along with Almodóvar's The Skin I Live In, is one of those ceremonial moments in a film festival. It is a chance to celebrate a lifetime of interesting work by rewarding something impeccable but unexciting. Mortensen has done great stuff for the Canadian director. Fassbender is one of the hottest actors of today. And Knightley is, well, the flavor of last month. But if this was meant to generate the kind of excitement that arose from the David Finccher-Aaron Sorkin collaboration The Social Network last year, or the level of pop-historical genius the NYFF jury anointed in the Stephen Frears-Peter Morgan partnership that produced The Queen for NYFF 2006, they were very sadly mistaken.

A Dangerous Method, one of two NYFF films starring Michael Fassbender (the other being Steve McQueen's Shame), will be released by Universal Pictures in the US November 23; in the UK February 10, 2012.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-20-2021 at 11:18 PM.

-

Sean Durkin: Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011)

SEAN DURKIN: MARTHA MARCY MAY MARLENE (2011)

ELIZABETH OLSON AND SARAH PAULSON IN MARTHA MARCY MAY MARLENE

Nowhere to run

This Sundance Institute-assisted film by the very talented young NYU Film School-trained director Sean Durkin begins with its protagonist's dawn escape from the Catskills cult she's been living with for two years. She's followed and approached at a village diner where she's having breakfast by a young cult member called Watts (Brady Corbet) but he lets her leave and she calls her sister Lucy (Sarah Paulson) on a pay phone. Corbet, of the Funny Games remake, is naturally creepy here; he plays a key minor role in Von Trier's Melancholia. That call is all we need to see this young woman's desperation and confusion. The title is a spread of names, because typically for a cult, its leader, Patrick (indie vet John Hawkes), gives new arrivals new names. She tells Patrick her name is Martha but he dubs her Marcy May. The skill of Durkin's beautifully shot and well-acted psychological horror movie is in the way it delineates Martha/Marcy May/Marlene's confusion in telling her story. When she is taken to stay with Lucy and her ambitious Brit architect husband Ted (Hugh Dancy) in their big rented lake house in Connecticut, she has no clear sense of space or time, and has lost her awareness of social and sexual boundaries as well.

Durkin conveys Martha's blurry, disturbed sensibility by the seamless, sometimes deliberately confusing way the film slips back and forth between the present and the cult experience, in some parts of which she can't distinguish memories from recalled dreams. The film's sly paradox is that though Patrick's commune had become nightmarish and dangerous enough for Martha to run away from it and it has left her fearful and paranoid, it was also seductive and pleasurable for her. Ironically, because Lucy's and Martha's family history is chilly and Lucy and Ted's judgmental bourgeois sense of boundaries leads them to see her as more in need of disciplining than of love and care, the place she has come to isn't warmer and friendlier than the place she has escaped from. Thus as Martha slips back and forth in her mind from the Catskills cult to the Connecticut household, she not only doesn't know who she is or how she should behave, but also doesn't know where the happy place is. No wonder she spends a lot of her time curled up in the fetal position sleeping.

Martha Marcy May Marlene isn't, therefore, a fun watch and isn't meant to be. The pleasure it gives is in the originality of its vision and its success can be measured in how uncomfortable it keeps you at any given moment. It's disturbing to find in flashbacks that Patrick seems seductive and even nice. He perceives that "Marcy May" wasn't appreciated by her biological family and he and the other cult members promise her a new warmer substitute family where everything, clothing, food, sexual favors, is shared; where she is recognized as "a teacher and a leader." Schedules and habits are new. There is only one meal a day in the evening, shared by women together, after the men, whom they outnumber. They seem radiant and happy despite shabby dresses, which they share indiscriminately. They choose their "roles," what work they will contribute. "Marcy May" becomes a good gardener, as Lucy notes when she has escaped. Patrick has sexual control, but his favors are looked on as an honor and delight. He tells "Marcy May" she is his "favorite." Of course all this is woven in confusedly with the present time where Martha says uneasily with Lucy and Ted.

Martha never tells Lucy where she has been or what has happened, and perhaps surprisingly Lucy never comes close to guessing. This is the viewer's situation in the film's early scenes. We don't know much about Patrick's farm, only that there was a big, shabby house, in the painterly images of the beautiful setting, smiling women, kids playing aimlessly and a little ominously outside. Judicious use is made of sound effects to convey disorder, fear, danger at the commune. But later Patrick's seductiveness appears when, before the others, he sings a folk song he has composed for "Marcy May." Eventually the dark side of the commune appears to us through the flashbacks -- darker and darker. Durkin is astute in portraying Patrick's ways of shaping and converting members subtly, never using shock tactics or exaggerating anything, relying on careful study of actual communes and cults -- but also not spelling too much out for us of the details.

There are climactic elements, underlined by the beautiful images of cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes and the quietly ominous sound design, but somehow the film feels a little too loosely edited in places and a little too open-ended in its finale.

John Hawkes has a key supporting role in this as he did in Debra Granik's Winter's Bone, and as he has himself noted both indie film breakthroughs featured young unknown female stars of beauty, assurance, and star quality, Jennifer Lawrence in last year's film and Elizabeth Olson in this one. Olson shines in the way she shifts from glowing to desperate, tentative to stubbornly resistant, vividly strange to Lucy and Ted, a motherly helper to newcomers at Patrick's cult, a shivering wreck at the two years' end. At the Connecticut house, she challenges her sister, and engages her brother-in-law's brittle wrath. There are a lot of modes here, and Olson slides into each of them as the film slides back and forth from present to past. Hawkes has an interesting role here too, gong from warm and welcoming to sleazy to scary and creepy from scene to scene.

Martha Marcy May Marlene debuted at Sundance in January 2011 and has subsequently been shown at Cannes, Toronto, and other festivals including the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center where it was screened for this review. It goes into limited US theatrical release (through Fox Searchlight) October 21, 2011, UK and France releases February 3 and 29, 2012, respectively.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-08-2014 at 01:40 AM.

-

Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne: The Kid with the Bike (2011)

JEAN-PIERRE AND LUC DARDENNE: THE KID WITH THE BIKE (2011)

THOMAS DORET IN THE KID WITH THE BIKE

Purity of emotion: love and hope (second viewing)

As I noted in the earlier review in my May Paris Movie Report, in The Kid with a Bike/Le gamin au vélo the Dardenne brothers are "on strong familiar ground," "depicting a troubled boy struggling to get attention from his derelict, immature dad and tempted to a life of crime by an older boy who exploits him." And the Dardennes' discovery, 13-year-old Thomas Doret, who plays Cyril, the 11-year-old reject, is "excellent, if quite uncharming and uncute." But what I ought to have noted was not only the incredible drive Doret has but the emotional wallop the film packs. I was more deeply moved this time, viewing the film again at the New York Film Festival.

It's telling that the Dardennes cast Jérémie Renier as Cyril's derelict dad. Renier was a kid of 15 himself in 1996 when he played the son to Olivier Gourmet's reprehensible dad in the Dardennes' breakthrough La Promesse, and Thomas Doret may well go on to have an acting career like Renier. I noted that Cécile de France, who plays Cyril's working class, hairdresser surrogate mother, adds her usual "perky good looks and soul." But I ought to have added that de France's role adds a sweetness and warmth and hope unusual in a Dardenne film up to now. And of course love, the thing Cyril needs and so ardently seeks, sometimes in just the wrong places.

There has been no moment in the 2011 New York Film Festival as heartbreaking as the scene when Cyril's cowardly dad, forced by Samantha (de France) tells the boy he doesn't want to see him any more, ever, and the boy acts out his hurt and anger in Samantha's car. Then Cyril has his period of going bad, falling for the offer of preference and friendship he gets from the gangsterish Wes (Egon Di Mateo), who merely trains him to assault and rob a man carrying money from his newsstand sales, along with his son. Then comes Cyril's apology and Samantha's agreement to pay the damages, and the later fight between Cyril and the man's son.

When all that is over, and he's been even more decisively rejected by his dad, Cyril tells Samantha he wants to live with her full time, and they do.

I wrote in May that "What's so great with the Dardennes is the irresistible force of the chase, the hunt, or whatever is going on in the somewhat dogged narrative at hand, and a use of actors and non-actors so seamless that one never has a chance to stop and think 'this is a movie.'" Cyril goes everywhere at breakneck speed and he may have a more intense drive than any previous Dardennes character. But his dad stops Cyril, and so does his failure with Wes. So Cyril escapes from the group home, gets into his dad's former apartment, finds his dad, gets his bike back every time it's stolen, even carries out Wes' robbery plan, but it's all as nothing, because he has no one and is nothing till he accepts Samantha. Samantha, as I said in May, is "a saintly woman with tough love." And she's willing to deal with Cyril, even though he's such a handful. When her current boyfriend Gilles (Laurent Caron) says "you have to choose him or me," she says, "Him."

The film not only "ends on a note of hope." It is idyllic, when it shows Cyril and Samantha riding bikes together and going for a Sunday picnic. It suggests that they can have a nice life together, if he stays away from people like Wes in future. This isn't the Dardennes' only highly emotional film. Their films are often full of heartbreak and also full of forgiveness. But the level of hope here is unusually high, and I don't think it's a softening, just an affirmation.

The camerawork by Alain Marcoen is not jerky, as some have suggested. As I wrote earlier it is "(for these filmmakers) smoother than usual." What is also different, as was noted by Jean-Pierre and Luc at the New York Film Festival P&I press conference, are moments of music, powerful bursts of classical strings that evoke Italian neorealism. They said this was nearly a first for them, and that it added an element that was lacking in Cyril's life, the "element of love." I was struck this time by how those short bursts of music introduced to celebrate Cyril add a powerful note of humanism and warmth. This is an understated but very strong addition that I failed to note before but was strongly aware of this time. Again I was struck by the fact that the Dardennes' complete control over their medium, simple and single-minded, keeps our attention riveted for every minute of the film. It's a technique that leaves one feeling exhausted but fulfilled. The film seemed more emotional and more positive to me this time. It doesn't really matter that the directors are on more familiar ground than their previous Lorna's Silence. The emotional power, the intensity and speed of the little protagonist, and the positivity are something a little new, and the sense of things being just a little too much manipulated (but with masters' hands) is really no stronger here than it has been in nearly every one of the Dardennes' previous films. I am more impressed than I was in Paris and think this is brilliant work. But I understand why after so many at least superficially similar works the Cannes jury doubled this up with Nuri Bilge Ceylan's film and I very much understand why that film did not get a prize all to itself. I merely question whether it should have won anything.

I first watched The Kid with the Bike May 18, 2011 in Paris, the day of its French theatrical release. I watched it again October 5, 2011, as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. The directors were present afterward with Richard Peńa, Film Society director, for a Q&A. As mentioned before, the film co-won the Grand Prize at Cannes, sharing it with Nuri Bilge Ceylan's Once Upon a Time in Anatolia. The film has been bought for US distribution by Sundance Selects, to be released in March 2012.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-24-2022 at 02:00 PM.

-

Steve McQueen: Shame (2011)

STEVE MCQUEEN: SHAME (2011)

CAREY MULLIGAN AND MICHAEL FASSBENDER IN SHAME

A cold wall of sex in Manhattan

Steve McQueen is the Turner Prize-winning British artist whose stunning depiction of the imprisonment and death of Bobby Sands in Hunger (NYFF 2008) won the first-time filmmaker Caméra d'Or award at Cannes in 2008. Hungerstarred Michael Fassbender in a physically wrenching performance that put him on the international map as a film actor. Fassbender and McQueen have teamed up a second time for an equally extreme but far different theme in Shame, a film about a handsome but very cold New York corporate employee who is a raging sex addict. Along with Fassbender, whose character is called Brandon, Carey Mulligan ups the acting level further in an excellent performance as Sissy, Brandon's garrulous and needy sister, a cafe singer, who temporarily moves in with him. Nicole Beharie is fine as Marianne, a coworker who tries to have an affair with the intimacy-averse Brandon, and James Badge Dale is good as David, Brandon's fast-talking boss. This shows that for Fassbender, who since Hunger has been increasingly in demand and delivered some brilliant performances for other directors, particularly Quentin Tarantino in Inglourious Basterds and Andrea Arnold in Fish Tank, demonstrates that McQueen may still be the Scorsese to his DeNiro. This is a collaboration that produces outstanding work. But this being a glass-and-steel study of alienation and lack of affect, it doesn't provide the kind of catharsis Hunger did, nor does its style, though elegant, have the rigor and intensity McQueen achieved in his remarkable first feature.

The emotional numbness of the addict and the sense of desperation are evident from the opening sequence, where Brandon prepares for work, ignoring desperate phone calls (they later turn out to have been from Sissy), masturbating hastily in the shower, walking around in a display of casual frontal nudity that shows the necessary equipment is in good order but the face on the man is wary and strained. Again in contrast to Hunger, which shows a precise progression, Brandon's life of wanks, online porno, quickies with pickups and visits from prostitutes without meaningful communication or friendship, produces a sense of narrative as well as emotional chaos. The question gradually arises, How should we care about this man? The answer is that we slowly begin to feel a mixture of pity and disgust, but the caring comes in with the surprise appearance of Carey Mulligan, nude, in Brandon's bath. No information about the siblings, but he says (logically, since it's true of the actor) that he was born in Ireland but they grew up in New Jersey. It's obvious they share some kind of painful family background, and that they are all each other has. Brandon cannot acknowledge need; Sissy can do nothing else. "We're not bad people," Sissy tells her brother. "We just come from a bad place." Sissy is a lost soul, but her despairing warmth saves the film from being as frozen as the deepest bolgia of Dante's Hell.

There are several memorable sequences. In one, Sissy performs the slowest ever version of "New York, New York" in a stylish cafe watched by David and Brandon. Brandon can't seem to muster even mild enthusiasm for Sissy's performance, and perhaps to compensate, she has sex with David later in her brother's apartment, where she's now staying. Further along, Brandon's date with Marianne begins with awkwardness and a silly waiter in a restaurant and ends without a kiss or a hug. The next day Brandon hits on Marianne heavily at work and they end up in a showy room at the Standard Hotel at the High Line but the fact that she really cares for him makes him impotent. He asks her to leave and calls in a prostitute whom he showily screws up against the big plate glass window. Finally, Brandon goes into a downward spiral into the wild side that includes a gay rough trade bar and a seedy dive where his obscene come-on to a woman in front of her husband gets him beaten up. Meanwhile once again he is ignoring Sissy's increasingly desperate calls, with a dire result that somehow may be positive.

At the New York Film Festival Q&A McQueen and Fassbender showed a camaraderie that was quite the opposite of the film's chilly anomie. McQueen's answers showed his purpose was indeed to make a movie about sex addiction, and Shame was set in New York because true-life informants about the subject were available there and unwilling to talk in London. The director alluded to Days of Wine and Roses but here the addict never acknowledges his problem or seems aware of his downward spiral -- except in the gesture of throwing out his porn collection. The film seems to adopt a detached, aestheticized, almost glamorizing view of addiction, though this may not have been at all intended. New York becomes a hell of sterility and coldness that the two talented collaborators may not have understood as well as London -- a place a little too like Steven Soderbergh's affectless call girl's surroundings in his chilly digital The Girlfriend Experience, though this is clearly a richer and, despite the protagonist's isolation, a warmer film. Cinematographer Sean Bobbitt and editor Joe Walker, who worked on Hunger too, continue their style of powerful long takes, but the familiarly cold Manhattan setting and dislocated sensibility make this more like other films than McQueen's distinctive debut. A hero's struggle for national liberation must inevitably engage more than the conundrum of a dysfunctional modern urban man's inaccessibility even to himself. I would rather that Bach's keyboard music (even the immortal Glenn Gould recordings) were not elicited as a theme. Bach has not been so debased since Silence of the Lambs.

Shame debuted at Venice and was shown also at Toronto; and New York, where it was screened for this review. Fox Searchlight bought the film for US release, planned for December 2, 2011. The French release is to be December 7; UK, January 13, 2012. In the US it has received an NC-17 rating.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-14-2011 at 12:32 AM.

-

Wim Wenders: Pina (2011)

WIM WENDERS: PINA (2011)

PINA IN "CAFÉ MÜLLER"

Modern dance from Germany in 3D

Wenders' appropriately austere, stylized documentary about the German modern dance master Pina will appeal to her fans and students of her work. Philippina "Pina" Bausch, who was born in 1940, was a German performer of modern dance, choreographer, dance teacher and ballet director. She died in 2009, suddenly after a cancer diagnosis, having collaborated on this film. Wenders' film which is in 3D, presents a continuum of Pina's work, usually ensemble dance pieces in a stylized modern urban setting. As the film progresses a succession of Pina's dancers are seen facing the camera in front of the stage of dancers as a voiceover of that person reminisces or speaks of Pina's influence on him or her. The style of the film is as pared down as the style of the dances.

Featured in the film are two of Pina's most noted dances, both originally from the Seventies, first, a version of Igpr Stravinsky's Rite of Spring in which the stage is covered with soil and the ensemble, in loose robes, make energetic, sweeping arm movements; next the lengthy and complex Café Müller, wherein dancers move sometimes haltingly around the stage crashing into tables and chairs arranged as in a cafe that themselves are moved about.

The Pina style is highly surrealistic. Pina Bausch's company Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch acquired a global reputation and influence while touring the world, and debuted in the US at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in the mid-Eighties. The work makes use of elaborate sets and multiple media. The gestures of the dancers often have a mime quality. One of the pieces is featured in Almodóvar's film Talk to Her, in which it helps to establish that film's strange, surreal feeling.

Not being a fan of modern dance or previously acquainted with Pina I found this film intriguing in some ways, off-putting in others. The dancers seemed often very gaunt and sad looking. Some ensemble movements even suggested a crowd of concentration camp survivors. Personally I rather missed the earlier much warmer Carlos Saura music and dance films, the 1995 Flamenco and the 1998 Tango and his Fados (NYRR 2007), which are all enormously entertaining. It seemed to me that relatively speaking this film worked less as musical and dance entertainment and more as a record and homage. However, given Wenders' many fans and Pina's iconic status, this film will have an audience. The 3D here was, arguably, smoother than its use in the NCM Fathom "event" last summer of "Giselle" presented by the Mariinsky Ballet in St. Petersburg. Nonetheless it seemed again that dancers appeared Photoshopped onto backgrounds at times and the value of onscreen-with-tinted-glasses 3D to cover performance events still eludes me. But other viewers at the screening were already admirers and enthusiastic about the film. They urged me to try a second look. .

Pina has been shown at a number of international festivals, starting with Berlin in February 2011 and interspersed with releases in a number of countries. It is included in the New York Film Festival in October 2011, where it was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-07-2011 at 09:25 AM.

-

Nadav Lapid: Policeman (2011)

NADAV LAPID: POLICEMAN (2011)

YAAL PELZIG AND MICHAEL ALONI IN POLICEMAN

Cops meet kids in the new Israel

Young Israeli director Nadav Lapid's Policeman/Ha-shoter (in Hebrew, with English subtitles) is a first feature that boldly takes on two timely and controversial subjects in Israel: police brutality and social unrest. After two segments devoted separately to these elements, the film brings them together in a violent confrontation in which anti-terrorist special police sent in to stop the kidnapping of billionaires at a wedding party emerge as essentially terrorists themselves. Explosive material, and an exciting finale. Lapid knows how to bring scenes to life. But he still needs to improve in the writing and editing departments because the three segments do not interrelate smoothly and tellingly. In fact they barely go together at all.

The character we meet first and get closest to is Yaron (Yiftach Klein), the most macho of a macho unit of elite antiterrorist Israeli police. We see him at length exercising, then massaging his pregnant wife, then hanging out with his team. Their targets are usually Palestinians and there's some sort of legal case in which they're being held liable for collateral killings of Arab family members. One of the team members appears to have cancer, and Yaron asks him to take the rap, on the assumption that his treatments will exempt him from going on trial. Is it possible there's the further assumption he may die and therefore is expendable?

The antiterrorist cops engage in an exaggerated machismo that's homoerotic and slightly juvenile, hugging and high-fiving all the time, caressing their pistols in front of cute girls and calling each other "warrior." Yaron's pride in fatherhood -- another proof of virility besides his muscles and dangerous job -- is underlined by the way he boasts of his wife's being about to give birth, even posing in front of a mirror holding somebody else's baby to see how he'll look as a dad. The men show off their support of their emaciated, ill member, cutting short a cycling ride to stay within his capacity, promising to take him to the hospital for an important test, and all playfully throwing him into the sea when they go for a swim. Lapid adopts an intense physicality in these early sequences.

When he moves on to the angry young bourgeois revolutionaries the concern is less macho and physical and more esthetic. They are led by Natanel (Michael Aloni), who's as beautiful and blond (and slightly sickly) as Yaron is brutish and ordinary. His co-leader is a small poetess, Shira (Yaara Pelzig), who's all attitude. In fact she spends most of her time pouting and putting down the other guys (Shira, she hints, is the one they "all love") and repeating lines from a revolutionary declaration she is planning on reading to the media at the height of their operation.

This segment is introduced with a bridging scene in which Shira passively watches a group of leather punks totally demolish a small car, which turns out to be hers. She may applaud this gesture because the car is paid for by her parents, whom she despises, but the scene makes no particular sense and underlines the film's lack of good links.

ven the billionaire wedding is a bit awkward because it is staged and shot to look quite rinky-dink (perhaps it's meant satirically?). But once Natanel, Shira, and their little band emerge from their disguises and start terrorizing the party and seizing its main members as prisoners, things become compelling and energetic. When the kidnappers are all together with their prisoners in what looks like a parking garage and notify the press, Yaron and his team are called upon to intervene, following an advance guard of two fake press photographers who take photos of the kidnappers for the cops to use to identify them when they break in. In the event that's hardly useful. The killings are pretty indiscriminate. Before that one of the young terrorists impulsively kills one of the billionaires. This act further highlights the relationship between the killer and his father, a veteran leftist who has come along for one last revolutionary tango but has second thoughts, as do others.

Lapid has Shira underline the link between the elite police and the young extremists by repeatedly yelling in a megaphone "Policemen, you are oppressed too!" But this is mocked by Yaron, whose new problem is dealing with the unheard-of fact that their enemy targets this time are not Arabs but Jews.

In a statement by the director published when the film was shown at the Workshop section of this year's Cannes Festival, he declared that Israel was "socialist, basically egalitarian" in the Sixties and Seventies when "political terrorism rose in western Europe," but now despite the way it's masked by facing the Palestinians as a "common enemy," Israel today "has the widest economical gaps in the Western world" and "below the surface, boils a rage and a feeling of abuse." Policeman, he suggested, is meant to bring this below-the-surface rage to a head in its dramatic finale.

Policeman is more interesting as a timely artifact than as a finished film. Its awkward construction and imbalance in characters -- Yaron is far more fully explored than the young revolutionaries -- keep it from working structurally or artistically. Alissa Simon of Variety views the film as smashing together "two types of tribalism" and suggests that the punks who trash Shira's car and the lesbians and artists she meets at the nightclub the night before the operation are other tribes. Simon comments that Policeman "has a conceptual rigor that doesn't always translate into compelling viewing or even a smooth narrative whole." I think Policeman is drawing attention for its current and provocative subject matter rather than for its execution. "Conceptual rigor" is a slightly misleading term since the film is not so well conceived as a film, despite its bold thinking about national issues.

Several writers have described the acting as stylized, at least on the part of the revolutionaries. This is probably true, and it ill fits with the intimacy of Yaron's scenes at home. There are some good images outdoors and during the violent finale, helped by the cinematography of Shai Goldman, who shot The Band's Visit.

Lapid wrote the script of Policeman at an earlier Festival de Cannes Residence, and the film debuted in 2011 at Locarno (where it won a special jury prize) and was shown at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center in October, where is was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-08-2011 at 04:50 PM.

-

Simon Curtis: My Week with Marilyn (2011)

SIMON CURTIS: MY WEEK WITH MARILYN (2011)

MICHELLE WILLIAMS AND EDDIE REDMAYNE IN MY WEEK WITH MARILYN

Chaperone, hand-holder, and would-be lover

In this lightweight but star-studded, touching, and richly produced British entertainment from a memoir (adapted by Adrian Hodges), Eddie Redmayne plays Colin Clark, a patrician young third assistant director (and the memoirist), son of the renowned art historian Sir Kenneth Clark, who has a brief romance with Marilyn Monroe (Michelle Williams, again showing her range and skill). This happens during the 1957 Pinewood Studios shooting of The Prince and the Showgirl, which co-stars Laurence Olivier (Kenneth Branagh), who also directs, and is embarrassed to have had to bring in Marilyn to replace his wife, Vivien Leigh (Julia Ormond) -- who played the role with great success on stage, but is too old, at 43, to reenact it on screen. The cast includes Dame Sybil Thorndyke -- played here by another Dame, Judy Dench -- who, having absolutely nothing to lose, is one of Marilyn's warmest supporters. Also on hand for this film is Derek Jacobi, and a bevy of good younger English actors, including Toby Jones, Dominic Cooper, and even Harry Potter's Emma Watson, as Lucy, a wardrobe girl Colin briefly dates until Marilyn sweeps him away.

Marilyn, of course, requires a great deal of attention, and that's where Colin comes in. She drives Olivier nuts by always showing up very late on set, repeatedly blowing even simple lines, and rushing off the set in a tizzy. To reassure her, she has her very own Method coach, the master Lee Strasberg's wife Paula (Zoë Wanamaker) on duty 24/7 to "coach" her. Olivier thinks little of Method acting. In his opinion, if Marilyn doesn't "feel" her part, she should just buckle down and pretend. Paula's coaching mainly means telling Marilyn over and over what a great actress she is. But that's not enough. The blonde star's brand new husband, the playright Arthur Miller (Dugray Scott), decides she's "devouring" him and returns to New York, leaving her alone -- a state she cannot stand to be in.

And so it is that young Colin, who's already proven himself a first-rate gofer and fixer, gets his moment to be the essential man. Marilyn must have company, and warmth, and a little romance. Despite initial restraint, and loyalty to Lucy, he soon relents and falls madly in love with her. He spends a couple of days with her, taking her on a private tour of Windsor Castle -- his godfather Sir Owen Morshead (Derek Jacobi) happens to be the librarian -- and to his old school, Eton (where Ms. Willliams is surrounded by a flurry of real Eton schoolboys and impulsively kisses one), and to a park where the pair go skinny dipping, and kiss. Colin actually spends a night in Marilyn's bed. This happens when she has taken too many pills and can't be reached, and the production staff send Colin up a ladder into her bedroom window. Later she apparently has a miscarriage.

This is a euphoric memoir, not so much about events as about a young man's starry-eyed feelings. It reminded me of Richard Linklater's 2008 Me and Orson Welles, another story of a young man's brief encounter with thespian greatness, Mr. Welles and his revolutionary Mercury Theater production of Julius Caesar. The young man, played by Zac Efron, isn't an Old Etonian with impeccable manners, just a high schooler from New Jersey. But he's romanced too, and dropped, and he too has a backstage girlfriend who becomes disappointed in him. Me and Orson Weles doesn't have the same glitter, but it has good impersonations too, and recreates a moment in acting and stage history and a young man's disillusion.

Eddie Redmayne acts out the enchantment and the disillusion beautifully, but the larger pleasure of My Week with Marilyn is its evocation of the moment. The film was shot in the very Pinewood Studios where The Prince and the Showgirl was filmed in 1957; Michelle Williams acts in the house where Marilyn stayed during the shoot. One is meant to savor the impersonations. Michelle's of Marilyn holds the spotlight as did Marilyn herself during her short life as a star. But this is a traditional English film and hence very much an ensemble work -- a collective celebration of the arts of acting and filmmaking; and the production values, cinematography, sets, music, are golden. It's conveyed to us that despite her monumental insecurities and hopeless background, Marilyn Monroe was screen magic. She had trouble getting her lines right, but when she did, they were zingers. Branagh's serio-comic turn as Olivier is one of his better recent roles; Julia Ormond's Vivian Leigh is tasty and elegant; Dame Judy's Dame Sybil is warm and charming. Dominic Cooper is memorably aggressive as Marilyn's partner and photographer, Milton H. Greene; Toby Jones, appropriately annoying as some American toady.

As Marilyn, Michelle Williams shivers and glows. She can't look quite like Marilyn or be as beautiful. But her hard work pays off in her song and dance numbers; in the way she moves when she wiggles and walks; in the way she fills a dress; and she goes through a wealth of facial expressions. Eddie Redmayne, who recently won two awards, in London and New York, for his performance in the play Red, happens to have actually gone to Eton himself, then Cambridge (Colin went to Oxford, close enough). He is a tasteful, understated actor, and has the fresh face to convey the blushing young man, an amalgam of good manners and eagerness who, as the jealous Lucy puts it, needed to get his heart broken, and happily did. This may not be a great film, but it's impeccable and fun, and it looks likely to draw some attention at Oscar time.

My Week with Marilyn had its world premiere October 9, 2011 at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review. Harvey Weinstein produced, and theatrical release is scheduled for November 4, 2011 in the US, November 8 in the UK.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:05 PM.

-

Pedro Almodóvar: The Skin I Live In (2011)

PEDRO ALMODÓVAR: THE SKIN I LIVE IN (2011)

ELENA ANAYA IN THE SKIN I LIVE IN

Beautiful surfaces

[w a r n i n g: . . .p o s s i b l e ... s p o i l e r s]

"Austere" is how Almodóvar describes the style he strove for in his new film, The Skin I Live In (La piel que habito) whose story of an unscrupulous plastic surgeon who creates a forced sex change to simultaneously "replace" his lost wife and avenge the rape of his daughter evokes B-horror. "Austere" may sound pretty ironic given the lush beauty of the images, the intensity of the music, the rich, beautifully lit sets, and the handsome actors elegantly dressed by Paco Delgado, working with Jean Paul Gaultier. But in this film, whose screenplay is adapted from Mygale, a noir novel by the French writer Thierry Jonquet, Almodóvar does hold back a measure of his usual humor, jaunty color, and over-the-top campiness. Although there are moments, as when a husky man in a cat suit bares his ass for a surveillance camera so his mother will recognize him, that are absurd and funny. Antonio Banderas, who starred in the director's earliest films, is back, at 51, looking every inch the glossy but slightly over-the-hill B-picture leading man and exercising impeccable restraint as the evil co-protagonist.

"Strange," "twisted," and "surreal" are words that have been applied to Jonquet's novel. Almodóvar has beautifully elaborated and elucidated that original and removed some of the rougher and more poignant elements. As he retells it, the tale gradually reveals its secrets so the revelations are satisfying rather than surprising and odd rather than moving, though the film's images themselves at times provide an exquisite pleasure. Jonquet's very short novel is ingeniously plotted. At the heart of it, as retold here, is a beautiful woman who is kept prisoner and who hates her victimizer but somehow cannot break away from him. It's a gender-bending sado-masochistic tale. A plastic surgeon loses his wife in a car accident in which she is terribly burned. She lives a while, but as her doctor husband is trying to save her, sees her charred, mutilated skin in a mirror and is so horrified she throws herself out the window. A daughter, psychologically delicate, is raped by a young man at a party where they are both high on drugs, hers medicinal, his recreational. She subsequently goes mad and throws herself out the window too. The young rapist works with puppets and with women's dresses and has a feminine side. The doctor kidnaps him and over a six-year period, transforms him into a beautiful woman who resembles his lost wife -- and has a skin that is impervious to fire. Needless to say, the relationship between doctor and imprisoned patient is uncomfortable, and it becomes strangely ambivalent.

The theme is one in which personality is seen as not tied to gender. Nor, evidently, is film quality tied to genre, since Almodóvar is evoking trashy Hollywood film but adding a high-art gloss. As Amy Taubin has written in Art Forum, Skin "effortlessly synthesizes the mad-scientist horror flick; a contemporary resetting of a nineteenth-century grand opera narrative (motored by the desire for revenge and filled with dark family secrets); and the most perverse strain of the Hollywood 'Woman's Picture,' where the heroines are wrongly imprisoned in insane asylums or hospitals and treated as sadistically as lab rats."

The director may see himself as a kind of Dr. Frankenstein himself, and also as a Pygmalion: he has played Henry Higgins to stars like Banderas and Penélope Cruz. His "victims" in this film are Vicente (Jan Cornet), the rapest, and Vera (Elena Anaya). The evil doctor is Robert Ledgard (Banderas), whose ambiguity is perfect: he never seems anything but bland and impeccable. And his victims embrace him, and their new identity. Essential to Robert's elaborate house/clinic fortress is his housekeeper, Marilia (Marisa Paredes), who also seems to be everybody's mother. The prisoner is Vera, forced to wear a skin-colored body suit, sometimes masked, often operated upon, alternately trying to escape, commit suicide, kill Robert, or seduce him and make him her life partner. After an outsider's intrusion, a series of flashbacks describe Robert's daughter (Blanca Suarez) and Vicente (Jan Cornet), and tell us how they met and Vera came to be under Robert's care/control.

I find this film much more fascinating than Almodóvar's last two films, Volver and Broken Embraces, and his most haunting since Talk to Her. However I agree with the opinion Justin Chang expresses in his Variety review , that the director held back from fully embracing the darkness and perversity of his subject and, caught up in making something enchantingly beautiful, fails to get under our skin where we live as much as he should. The images shot by José Luis Alcaine are gorgeous. The interiors designed by Antxon Gomez are so original and handsome I wished I could linger over them longer. Alberto Iglesias' sweeping, pumped-up score is almost overwhelming, intoxicating. There are overt homages to Louise Bourgeois's sexually taunting sculptures, which are related somehow to the handicraft of Vicente: despite his relative "austerity" this time, as usual, Almodóvar provides more material than we can easily absorb. And on the other hand, according to Chang, he has elided some of the novel's "most emotionally rich passages." So once again it seems despite ample evidence of intelligence and rich cinematic talent and more power than other recent efforts, Almodóvar has allowed style to overwhelm substance. The fascinating gender (and genre) themes would haunt us more if there were more feeling.

La piel que habito debuted at Cannes in May 2011, followed by international film festivals and theatrical releases since the spring in various countries. Sony Pictures begins limited US release October 14, 2011. French and UK releases were August 17 and 26, respectively. Shown as one of the gala events of the main slate of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-20-2021 at 06:29 PM.

-

Joseph Cedar: Footnote (2011)

JOSEPH CEDAR: FOOTNOTE (2011)

LIOR ASHKENAZI AND SHOLOMO BAR-ABA IN FOOTNOTE

Bitterness and comedy in academe

The US-born Israeli filmmaker Joseph Cedar's last effort, which won the Silver Bear at Berlin, was Beatufort, a tense, excellent war film about a few members of the Israeli army making a dangerous last stand in south Lebanon in 2000. Footnote deals with a rather different topic -- textual analysis of the Hebrew Talmud. Now there's a change of pace, you will say. But not so much as might seem, because there is excitement here. Footnote is not an action movie but a tragicomedy -- about scholarly integrity; or is it futility? -- with enormous conflict, both repressed and open. It too, like Beaufort, centers compellingly on figures who wander a kind of half-abandoned but still dangerous battleground. It's also a deeply fascinating character study, and would warrant unhesitating recommendation were it not for a weak ending.

Footnote is full of the ironies that arise out of family and occupational rivalry. There is rich intentional ambivalence about the ways in which the film views each of its two main characters, father and son, both, -- this itself ironic -- Talmudic scholars. First is the father, Eliezer Shkolnik (Shlomo Bar-Aba), who has waited vainly for twenty years to receive the Israel Prize in his field. Cedar's own father, by the way, a biochemist, has received the Israel Prize in biology; he himself has studied the Talmud, so he knows whereof he speaks in more ways than one. Uriel Shkolnik (Lior Ashkenazi), Eliezer's son, is more popular among students and his peers, and receives an award as the film begins. At the awards ceremony he gives an ambiguous speech, mostly about his father, who sits stony-faced in the front row listening, not, it would seem, with any approval. The speech is entertaining, light, modest, a tribute to the father. But it also seems to mock him a little. Elieser already emerges from the speech and the way he listens to it as stubborn, dogmatic, and difficult. And if he is admirable, he is equally off-putting.

Elieser is a pure philologist, who approaches the text as a text. His son's work, which speaks more of manners and customs at the time of the texts, he disdainfully refers to as "folkloric." The father turns out to have examined one version of the linguistically problematic Talmud for decades, seeking to suss out inconsistencies. And then another scholar found the other text that caused them, and published his finding before Elieser could, rendering Elieser's decades of work irrelevant. Elieser is a monumentally dedicated scholar. But what has he accomplished? It seems his highest honor is being mentioned as a footnote in the work of another distinguished Talmudic scholar.

The whole film uses a sliding-back-and-forth visual format (with appropriate accompanying sound effect) in presenting its sections and images, to suggest what it's like to examine a manuscript on microfilm in a library. At first Footnote seems to be examining the career of Elieser Shkulnik as if it were itself a footnote or a small detail in a manuscript. But then come the bombshells. First, Elieser is walking, as he does every day, to the national library, to pursue his research, when his cellphone rings and he gets a call telling him he has won the Israel Prize. Then, a little later, Uriel is summoned to an urgent, secret meeting of the Israel Prize committee in a tiny cramped room, to be told that this has been a terrible mistake: he, Uriel, won the prize, not his father. (This is clearly the best scene, tense and confined like much of Beaufort. Some brief sequences showing Uriel to be a cutthroat squash player help to expand our sense of the undercurrent of violence in the events.)

We cannot reveal what happens after that, but it's suspenseful and thought-provoking, and leaves us perhaps forever in doubt as to who is the better man. Is one indeed less fatuous than the other? There probably hasn't been a much better or deeper or more telling on screen look at the jealousies and passions that surround certain kinds of academic work and the ways certain scholars (or brilliant, egocentric men) construct a fortress (a key word in the film) around themselves, the ivory tower protection from the real world. And the immense uncertainty of achievement in narrow fields that few understand or really know about. And then of course there is the question, held suspensefully in the balance almost to the very end: which will win out, professional ambition or family loyalty?

Cedar turns the finale into a meaningless extravaganza in which both the bitter and the comic sides of the story fade into mere spectacle. The film winds up feeling like a memorable little short story that, unfortunately, its author didn't know how to end. But even without an ending this is a strong and original film.

Other characters are also important, such as the chief back-stabber, Yehuda Grossman (Micah Lewesohn, whose brow looks like an exposed brain). Alma Zak and Alisa Rosen are good too as the wives of Urial and Elieser, respectively. And then there is also Uriel's young son (whose name I can't find), a beautiful young man, who is also ambiguous. Is he a useless time-waster, as Uriel suspects, or a free spirit about to choose a different, perhaps more interesting, path?

Footnote was in Competition in May 2011 at Cannes, where it was nominated for the Palme d'Or and won the Best Screenplay award, and also shown at Toronto and New York; at the latter it was screened for this review. Sony Classics has bought the film for US distribution. French release is slated for November 30, 2011.

.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-13-2011 at 10:46 PM.

-

Mia Hansen-Lřve: Goodbye, First Love (2011)

MIA HANSEN-LŘVE: GOODBYE, FIRST LOVE (2011)

SEBASTIAN URZENDOWSKY AND LOLA CRÉTON IN GOODBYE, FIRST LOVE

Honest look at early passion

Hansen-Lřve's first two films tackled subjects like family dissolution, addiction, and suicide. Her delicate, intelligent, naturally cinematic treatment of such challenging material has established her, at 30, as one of today's best young French filmmakers. That recognition evidently has given her the courage to go back to something simpler and more directly autobiographical, Un amour de jeunesse (the French title) -- a young woman's first passionate love. Nothing quite so harsh here as before in the world beyond the sensitive protagonist: some parents separate, perhaps, but happily, it seems; and nobody crashes. There is just the big task of mastering young emotion. The director's wonderful previous film, The Father of My Children, was more complex, but this one dares to be simple, and to go over material that may seem over-ridden with associations that risk cliché. Its bitter-sweet honesty in examining the traces left on a life by a first love seems essentially French. There is no cliché here. Again the young director approaches big events with bold honesty.

When the film begins the sweet and pretty Camille (Lola Créton) is only 15 and madly in love with a tousle-haired, adorable 19-year-old boy, Sullivan (Sebastian Urzendowsky). They constantly repeat their declarations of love, and make love, seeming to flow in and out of each other. But though sure of what he wants, Sullivan is uncomfortable in Paris and at the university and has already dropped out and decided to go to South America. After selling a valuable little painting to raise money for the trip he is off, leaving Camille behind. It is supposed to be for ten months.

Sullivan sends eloquent letters, but he can't bear to call and hear Camille's voice without being able to touch her. He writes a lot of letters, but then he stops. The film never quite resolves the issue of this departure and separation but there are hints that Sullivan has found Camille too clingy. She is sad, he is happy. Their idyllic trip to the Ardčche together that sun-kissed summer was spoiled because she was so troubled by his travel plan. Her melancholy at the prospect of his departure only hastened it. When he stops writing, she attempts suicide. It's a moment passed over quickly, however. Sullivan does not come back as promised. Eight years pass. Camille studies architecture. She finds a vocation, and an older lover, her Danish professor, a successful architect, Lorenz (Magne-Hĺvard Brekke), and she goes to work and moves in with him. The surprise is what happens when Sullivan reappears. As it turns out, it isn't over quite yet for either of them.

Uurzendowsky and Créton are excellent, attractive, natural, and spontaneous together, and Camille's experience of architecture is convincingly handled, as are the different personalities of the two men. What's obviously unrealistic to an almost Brechtian degree is that Camille and Sullivan don't age in eight years, and some see this as a flaw. Consider, as justification, that the 15-year-old and 23-year-old Camilles wouldn't look at all different from the viewpoint of a still later Camille. What makes Un amour de jeunesse work, even sing, is the naturalness and confidence and simplicity of Hansen-Love as a filmmaker. The technique is so seamless one wants already to watch the film again, because the nuances (particularly in the acting of the shy but volatile Créton) are complex enough to require multiple viewings.

As in the director's impressive two first features, the first of them made when she was only 23, there is a significant break in the middle, with the present understood later in terms of the past and the audience's established awareness of it. Hansen-Lřve has done it again, more delicately than ever, making a film that's both rational and emotional, in the French (and partly New Wave) manner, stating complicated things in a superficially simple way and structuring her tale in a style that emerges as more and more distinctive, but in a native cultural tradition. If Goodbye, First Love isn't as rich a film as The Father of My Children, it is still a subtle accomplishment, remarkable for its way of working out a past longing in the present.

Goodbye, First Love opened in Paris July 6, 2011, to very good reviews. It also was shown at Locarno (jury special mention), Telluride, Toronto, Chicago, and at the New York Film Festival, screened at the latter for this review. Its US distributor is Sundance Selects, and it will open theatrically in New York on Friday, April 20 at the Lincoln Plaza Cinemas and IFC Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-05-2012 at 01:33 PM.

-

Ruben Östlund: Play (2011)

RUBEN ÖSTLUND: PLAY (2011)

Realistic pseudo-documentary about teen robbers

Play is a realistic recreation of actual events using non-actors. The filmmaker read a news story about how in his native Swedish city of Göteborg (Gothenberg) a group of young black boys were convicted of carrying out over forty robberies of cell phones and other objects from white boys over a period of several years. They used ingenious methods they'd obviously worked out over repeated performances of their scam. The took advantage of the stereotype of black males as macho and menacing (and the non-black shame at revealing this fear) to seem to threaten their victims without actually using physical force. They also used what they loosely called a "bad cop - good cop" technique. One or more boys behaved in a threatening manner while another, the "good cop," would say something like, "He's angry and unpredictable. I'm not like that. I know you are probably right. But let's just go along with him, and check out the situation, and then there will be no trouble." The scam was for one of the robbers to ask one of the victims to show him his cell phone. Then he would say his brother had been robbed and this looked exactly like his phone that was taken away from him, had the same scratches. Then he would ask the victims to accompany him to go to see his brother. And during the long ordeal for the three trapped boys that follows, the five black boys obviously take great pleasure also in the sheer "Play" of making their victims squirmy and fearful.

This is about the pattern that is followed in the film with five black boys (Anas Abdirahman, Yannick Diakite, Abdiaziz Hilowle, Nana Manu and Kevin Vaz), who are African but speak Swedish, and three obviously better-off locals (Sebastian Blyckert and Sebastian Hegmar, who are white, and John Ortiz, who looks Asian). The robbers appear in a mall and later turn up causing a disturbance in an athletic shoe store. They begin following the white boys on a bus. The white boys go to a fast food restaurant and ask the women there to call the police. But they say they can't do that. Adults seem equally intimidated by the black boys, or afraid of seeming racist, and look the other way despite the black boys' provocative and annoying behavior.

Later the white boys, now under the robbers' control, are on another bus where the robbers cause a big disturbance, menacing and mocking other riders. Some adults, members of a gang, get on and attack the black boys, who get off with their victims, minus one, who stays on to escape. But one of the smaller black boys stays on the bus. When one robber boy tries to go home, the others beat up on him for doing that. Eventually the black boys take the white ones to somewhere out by a lake. This only ends when the black boys make the white boys put all their valuables, MP3 players, cells, etc, out on a nice jacket and stage a "contest" between one of them and one of the white boys, a race at which the black boy cheats and therefore "wins." Then the black boys go off with all the goodies, including a clarinet belonging to one of the victims, the Asian-looking John, and worth 5,000 kroner (about $750). John also loses his nice jacket and a pair of Diesel jeans.

The white victims run away and must take a tram or train home. They are without money and, one more of many ironies, instead of reporting they've been robbed, meekly say nothing, and instead of receiving assistance are fined (or their parents will be) for riding without tickets.

Meanwhile there is another lesser tale threaded through the film of a child's crib on a train. It belongs to an African family. At the end, two Swedish men attack two children from the African family and take away the cell phone of one of them, accusing him of being a robber. The boy screams and protests, believably, that he is honest and his large family has barely enough to eat, but when he is attacked he also, unlike the white boys earlier, strikes back hard, though he's too small to keep his cell phone from being stolen by the adult white vigilantes. Two Swedish women come and protest this illegal and unprovoked assault, but to no avail. Obviously this incident serves to balance out the implication, provocative to some audiences, that the only villains are blacks.

All this is shot in an "observational" vérité style with a middle-distance, largely immobile camera. The improvisation is quite successful, and the film succeeds in making the viewer very uncomfortable. Thanks in part to the "passive" camera and in part to the realism of the recreation it's hard not to identify with the victims and to be disturbed by the complex reactions about racial stereotypes that the action awakens. While we identify with the victims, at the same time ironically the victims tend somewhat, in the way of boys, who want to fit in to any group they're thrown in with, or in a kind of Stockholm Syndrome, to at times identify with and seek to please their black victimizers. Who, by the way, are not old, perhaps in the 11-15 range.

The action can be described as bullying, but it begins as a con game and ends as a kind of hostage situation. The victimized boys become prisoners in a prison without walls that consists of wherever the black boys take them.

This is said to be a follow-up to Östlund's 2008 film Involuntary, and in the past he has made documentaries. This is certainly anything but entertaining, but it's effective and thought-provoking, arguably more so than Michael Haneke's Funny Games, which it might otherwise be compared to. This is more realistic. But I would have to agree with Leslie Felperin in Variety when he describes this film as "formally interesting but far too long." In fact we get the point in ten minutes. Is it necessary for us to be tortured too in order to understand the nonviolent psychological torture the three middle-class white Swedish boys undergo? Felperin is right also in suggesting that this could be a "core text for civics classes." It makes points about stereotyping and racism that might be useful in a condensed form. It is also, perhaps, good for those members of festival audiences who enjoy suffering for a slow, torturous two hours and call films that bring about that effect works of art. Nonetheless this is a valid inclusion in a festival. That's the only logical place for it in this long form. Felperin suggests cutting half an hour. I'd suggest an hour.

Play, not to be confused with Alicia Scherson's poetic Chilean love story (SFIFF 2006) , has been included in festivals in Cannes, Munich, Helsinki, Vancouver, Toronto, and New York; it was screened in New York for this review. One theatrical release is pending, November 11, 2011 in Sweden.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-04-2011 at 10:57 PM.

-

Michel Hazanavincius: The Artist (2011)

MICHEL HAZANAVICIUS; THE ARTIST (2011)

JEAN DUJARDIN AND BÉRÉNICE BEJO IN A POSTER FOR THE ARTIST

Silent story