-

Nikola Lezaic: Tilva Rosh (2010

Nikola Lezaic: Tilva Rosh (2010)

MARKO TODOROVIC IN TILVA ROSH

Serbian skateboarders enjoy a last summer of youth

The film focuses on a long-haired skateboarder skating down a pebbly hill (he says its name is "Tilva Rosh") and from the subtitles we learn Serbian has equivalents for words like "Nigga," "dude," and "wazzup." Toda and Stefan have just graduated from high school, and are spending the summer shooting Jackass-style videos of each other as they skate the empty former copper mine in their town of Bor (no pun intended) while waiting for one of them to go off to college.

The two guys are Toda/Marko (Marko Todorovic) and Stefan/Steki (Stefan Djordjevic). Steki is going to the University of Belgrade shortly. Toda/Marko isn't, and says he wouldn't even if he had the money. Toda hurts his head doing one of their stunts. Later whenn the boys sing at a shindig the emcee, whom they tease unmercifully, hits Toda again on the head, so he goes to the doctor. But he finds he's no longer covered as a student and must go to the factory to sign up for the bureaucracy to provide him with medical coverage -- a situation that sorely challenges his sense of youthful independence. He has to go to a CV preparation class or he won't get the benefits of the Employment Service.

Meanwhile a girl called Dunja (Dunja Kovacevic)) is back from France on summer holiday, and both boys themselves compete for her attention.

The "dudes" do the things young people do, get drunk, act wild, challenge and harass a new member before admitting him to the skate club. There are many little rites of passage, including self-imposed piercings and the brutal Jackass-style abuse Toda and Steki impose on each other. Later, they all get involved in a demonstration against the scam to privatize the mine.

These boys and their pals and parents and everybody on the scene may speak an odd dialect of Serbian, but the youthful rivalries, the desire to hang onto teenage freedom while the realities of the bigger world are in their faces, are elements of a universal coming of age story, and these two guys have an authentic loosely-slung quality that can't be faked. In fact they were discovered by the director (whose name is usually spelled Nikola Ležaić; the titles is spelled Tilva Roš in Serbian) when he came across their set of Jackass-style stunt videos, which they called Crap, and found them hilarious. Crap was like a dry-run mixtape for Tilva Roš. The circumstances leading up to the film are very much a part of the film and so is the depressed mining area the actors and filmmaker come from. Tilva Roš means "red hill," and Stefan explains in the opening scene that this place where they begin shooting, which was once a big hill, is now only a big empty hole.

Several things distinguish the film: the naturalness of the performances; the specific sense of place; the sense of solidarity and identity that the youths have as a group. This is also one of the best films for showing young people hovering between childhood and adulthood. A well-timed climactic moment comes in the rambling story when the guys are hassling the bald-headed emcee for hitting Toda (against the wishes of Toda, who wants to forget about it) when all of a sudden they wander into a big demonstration of workers, and the skateboarders fall in with the march. It's as if all of a sudden they consent to stop being slackers and turn into citizens. Steki jumps on a police car and is cheered for videotaping the demo from there. But only minutes later the whole posse -- over a dozen of them -- are skating through a big supermarket and trashing the aisles as Steki films that. They seem to be just taking advantage of the protest to act wild.

The risky stunts of Steki and Toda are great acts of camaraderie. Everybody appears to be having an awful lot of fun, and there's a loose, summery style that starts with the long hair and the loose clothes everybody wears. And this includes most of the parents and other adults, who are mostly represented as sympathetic and laid back.

The film is cleanly photographed and sparing in its use of music. Lezaic gets the maximum from his young actors, who are splendidly real as variations on themselves. This stands as an essential contribution to the cinema of twenty-first century youth.

Tilva Rosh has been in many festivals, beginning with Sarajevo (July 2010), where it won the grand prize, and most recently at Rotterdam, Miami and San Francisco. It was screened at the San Francisco International Film Festival for this review.

SFIFF Screenings

Thu, Apr 28 9:00 / Kabuki

Fri, Apr 29 9:15 / Kabuki

Mon, May 2 3:15 / Kabuki

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:05 PM.

-

Otar Ioselliani: Chantrapas (2010)

Otar Ioselliani: Chantrapas (2010)

DATO TARIELACHVILI AS NIKO (LEFT) CONFRONTS SOVIET CENSORS IN CHANTRAPAS

Iosseliani ironizes his own professional history

The Georgian-born auteur, resident in France for 30 years, now in his late seventies, had his directorial extravagances and charm lovingly chronicled in Julie Bertucelli's 2007 documentary Otar Iosseliani, the Whistling Blackbird (SFIFF 2007). I also briefly reviewed Iosseliani's 2006 film, Gardens in Autumn>. It was shown both at the 2006 NYFF and the 2007 SFIFF.

Iosseliani's new film Chantrapas, though not explicitly autobiographical, is about a Georgian-born director who moves to France; and it is very much in the director's signature style. As Iosseliani has pointed out elsewhere, he himself escaped the worst aspects of Soviet censorship (even though he left to find greater artistic freedom). The director's more ironically drawn stand-in protagonist Niko (Dato Tarielachvili) is never so successful, and encounters serious obstacles even in France.

At the very outset Niko shows a scene from a new film to a former friend, Barbara (Tamuna Karumidze), who's become a government censor. A clip from an old short by Iosseliani himself, it metaphorically shows modern industry crushing all things beautiful in nature. Barbara says lose the film. He says no. He maintains this stubborn stance from then on, perhaps explaining the Russian slang title, which means "good-for-nothing." That would be what the Soviet authorities think of him. They're happy, eventually, to arrange for Niko's train trip to France, and nobody expects him to return.

It's always fun watching, especially this time in the Soviet sections, the director's typically elaborate, rambling staging of ensemble sequences, as he depicts Niko directing scenes from films that represent his youth while crew members wander in and out removing props as one scene or another is completed. At home Niko lives in a chaotic setting with his feisty grandfather (Givi Sarchimelidze) and grandmother (Nino Tchkheidze). Niko wins some victories with the bureaucrats when crew members support him, but he's the loser overall.

Niko arrives on the train, carrying a birdcage and a viola case, in a Paris where the streets seem to swarm with a multiculturalism dominated by hippies and Africans. He gets a producer (Pierre Etaix), but it seems that in some ways the old-fashioned world depicted in the earlier scenes was better, and Niko still seems to live in a quaint world, sending his grandparents messages via carrier pigeon and living in a rickety garret without mod cons.

Iosselliani shows his usual fluency and ease throughout, though the seeming casualness for some viewers may seem also to reflect a lack of urgency or momentum. The mise-en-scene and costumes, especially in the earlier Georgian sequences, are a pleasure to contemplate. For me this director is more to appreciate than to love. I seem to tend to remember certain sequences, without having much sense of the point of the whole. But if you like auteurs, here you've got one.

The 122 min. film, typically for the director, seems to know no restraints of time (Bertucelli chronicled his strong penchant for cost overruns). It was first shown at Cannes May 18, 2010, with a September 22, 2010 French theatrical release and other festival showings to follow, including at the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review, April 2011. French critical response was generally favorable, but Cahiers du Cinéma called this "an innocuous postcript" to a body of work already "highly recommended" and Excessif described the film as "charming but musty." "Charm" is a word frequently used, but some feel it more than others.

SFIFF Screenings

Sun, Apr 24 6:15 / PFA

Tue, Apr 26 6:00 / Kabuki

Fri, Apr 29 9:00 / New People

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:07 PM.

-

Christoph Hochhäusler: The City Below (2010)

Christoph Hochhäusler: The City Below (2010)

ROBERT HUNGER-BÜHLER AND NICOLETTE KREBITZ IN THE CITY BELOW

Steel, glass, money, ambition, sex

Christoph Hochhäusler is one of a group of younger German Wave (by locals called Berliner Schule or Berlin School) Teutonic directors whose work is marked by an icy coolness and a stern look at the modern world. Here his examination of the machinations of a cutthroat banking firm and its intersection with high-level adultery is so tense it feels like a muted thriller. There are hints at direness, while the fine acting keeps us riveted and the crystalline widescreen images ravish us. Emotionally, we're unnerved rather than moved, kept at a certain distance from principals whose motivations and backgrounds remain mysterious to us -- and probably to themselves.

New couple in town Svenja and Oliver Steve (Nicolette Krebitz, Mark Waschke) have only been in Frankfurt a few months for his job at Löbau Bank. Unemployed herself and seeking work, but doing something with large photographs, Svenja is at an art event when the cigarette she puts down for a minute is grabbed and puffed on by none other than Löbau's CEO, the icily elegant Roland Cordes (Robert Hunger-Bühler). This is the beginning of a mutual attraction the much younger Svenja is going to fight for a while, then succumb to.

The City Below concerns a high rise, megabucks world of passion and manipulation not unlike that of Alain Corneau's recent corporate noir, Love Crime. And there's murder here too, but at one remove. A Löbau executive in Jakarta has been killed and mutilated by kidnappers, though the Frankfurt managers decide to hush it up. They're going to move their Asian base to Singapore, but in the interim it's decided to shift Oliver, Svenja's spouse, to manage the Jakarta office on a temporary basis -- without his knowing anything about the fate of his predecessor. Meanwhile things have heated up between Svenja and Roland. The affair is a long time brewing; it's not until an hour into the movie that they finally go to bed. The relationship may be Roland's mad passion. But it's Svenja's whim that it should happen. Yet she doesn't at all want Oliver sent away from Frankfurt. Her world is too fragile. In the new steel and glass apartment she shares with Oliver some of the sparse furniture is still shrouded in plastic wraps. It seems the only stability for Svenja is her regular jogging.

While the affair continues its slow burn, other players move about in the chess game. Claudia (Corinna Kirchhoff) is Roland's elegant, handsome wife, unlikely to tolerate her husband's amour fou. Werner Löbau (Wolfgang Böck), the firm's president, is a bull-like, unpredictable man given to sudden tantrums. Andre Lau (Van Lam Vissay) is an Asian with perfect German who hails from Tampa, Florida. He is passed over for the Jakarta replacement job under suspicious circumstances.

All the while the Löbau partners are engineering a dangerous and destructive merger (or takeover, who knows?) that will put thousands out of work, a process they arrive at in the course of two meetings at a restaurant table. An early sign of the film's visual sensitivity is the way, as this deal is first sealed, the camera sneaks outside and views the men from the space outside the window. At the same time, despite the prevailing chilly mood, extreme closeups tend to heighten the most erotic moments between the illicit lovers.

Part of the distancing comes through Roland's feeding Svenja totally false information about himself, and using the fake name "Ritter" when they first go to a hotel (and that time do not make love). He has strange proclivities, such as liking to watch IV drug users. She has a burn scar from a risky past, and may have kinks of her own; yet she is intense about defending her husband when she thinks he's been used, and she has too.

Hunger-Bühler is an imposing actor with an off-putting presence. He seems every inch the rich, powerful man ready to make use of that power whenever he wants to. He tends to linger menacingly behind the shiny glass of his chauffeured Mercedes. When he asks Svenja if she's afraid of him it feels like she should be. But Krebitz conveys an instant sense that even in this world one need not be endowed with wealth to be formidable. She has, of course, the power of youth and style, but it's her utter self-possession that counts most. Svenja is definitely Roland's match, and is so by sheer chemistry. The mystery of the two people and the magnetism that links them is underlined by light and shadow, reflected glass and exposed flesh in Bernhard Keller's assured, elegant camera work.

The drama continually builds. Yet things never quite gel. The moment of chaos signaled in the final shot may seem tacked on. But this is not altogether a failure. Hochhäusler is clearly more interested in sowing the seeds of disquiet and in cutting away economic power to show the animal passion underneath than in unspooling a thriller like Corneau's. On the other hand, while the coldness impresses, the rigor chokes off some of the passion that's crying out to be released. "Cold German" is a tired cliché that may still sometimes be true.

The City Below/Unter dir die Stadt, in German, 105 min, co-written by Hochhäusler and Ulrich Peltzer, debued at Cannes in May 2010. Theatrical releases in France December 15, 2010 and in Germany March 31, 2011, with three showings at the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review.

SFIFF Screenings

Fri, Apr 22 9:30 / Kabuki

Mon, Apr 25 4:00 / Kabuki

Apr 29 6:00 / Kabuki

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:31 PM.

-

Alejandro Chomski: Asleep in the Sun (2010)

Alejandro Chomski: Asleep in the Sun (2010)

CARLOS BELLOSO AND ESTHER GORIS IN ASLEEP IN THE SUN

Disquieting whimsy from Buenos Aires

Chomski has made an elegantly droll little piece of cinematic surrealism set in Forties Buenos Aires and based on a 1973 story by well-known Argentinian writer Adolfo Bioy Casares, whom the filmmaker knew, but who died a decade before the film was completed. Lucio (Luis Machín) is a watchmaker who works out of the boyhood home he inherited from his parents when they died in an accident. He lives with an elderly woman servant, Ceferina (Norma Argentina) and his wife Diana (Esther Goris), whom he dearly loves but who has become strange. She's obsessed with dogs and overly attached to a certain Dr. Standle (Enrique Piñeyro) and spends an inordinate amount of time at his canine clinic trying to decide upon a pet. Lucio consents to Diana's being sent to a so-called "Phrenopathic Institute" for treatment, under the care of the mysterious Prof. Dr. Reger Samaniego (Carlos Belloso), whose large office is a symphony of light and shadow. Art direction does not take a second place in this methodical, attractive film.

He is disturbed when they won't let him visit her, and then when she's released, equally disturbed by her changed personality: she dances, performs fellatio, goes for walks with him, and whistles. When he goes to complain at the clinic that his wife is no longer the same person, the director says he's changed too, and abruptly inducts Lucio as a patient. "Escape if you can," says a friendly nurse. Everyone here and at the dog clinic is dressed in immaculate starched white uniforms. Black Forties cars tool about quietly, and the interiors and architecture of the clinic are deliciously dated: this is a film for the eye to savor. It's oddities aren't meant to alarm so much as to bemuse. As Lucio, Luis Machín, who is in nearly every frame, has a soothing conventionality, even though he's a reserved, Kafkaesque nobody.

Eventually things become very wacky. Dr. Samaniego's Phrenopathology seems to involve moving souls from one body to another, and some human personalities wind up in the bodies of dogs. Details are lacking, and one comes back to the fact that this is a short story, and not one that the filmmaker has fleshed out as fully as appears at the outset. The actors provide a sense of texture where there is not so much, and the impressive art direction fills in the rest. Elements in the work of Adolfo Bioy Casares are the impossibility of amorous relationships, the insertion of a fantasy world into reality, philosophical speculation and the distancing effect of humor. They all come together here, though ultimately they make Asleep in the Sun thought-provoking, but not emotionally satisfying. This is Kafka with a whimsical touch. The disquiet is slow in coming but builds in a rush in the final scene, a wake where dogs and people have traded personalities.

Asleep in the Sun/Dormir al sol debuted in Argentina in 2010, and was shown at the Jakarta festival in November of 2010. Screened and reviewed at the San Francisco International Film Festival, April-May 2011.

SFIFF Screenings

Sun, Apr 24 8:45 / Kabuki

Thu, Apr 28 3:30 / Kabuki

Sat, Apr 30 6:15 / New People

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:13 PM.

-

Tatiana Huezo: The Tiniest Place (2011)

Tatiana Huezo: The Tiniest Place (2011)

THE TINIEST PLACE IS ALSO A SINGULARLY BEAUTIFUL PLACE

Poetic documentary about people, a village, survival of civil war

The village of Cinquera, El Salvador, on the edge of the jungle, is a place haunted by the ghosts of a brutal civil war. In the years between 1980 and 1992 Cinquera was virtually annihilated by the National Guard because they thought it a haven for the liberation front, the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional. Now decades later survivors of this onslaught have returned to bury their dead and have rebuilt the town from what remained. Under the rightist government Cinquera was officially removed from the charts. Over the country as a whiole there were perhaps eighty thousand deaths and tens of thousands who disappeared. Now Cinquera is a town again, with a school, a band, and lots of cows.

Tatiana Huezo is a young Mexican documentary filmmaker who was born in El Salvador. In this superb debut feature she paints a portrait of the whole village and its collective personality. She does that by observing villagers recalling their ordeals, which include all kinds of brutalization and cruelty, causing madness. An old woman still talks continually to her deceased daughter. In fact many who escaped from the town into the forest joined the FMLN. Its flag still flies on the sides of some houses. Likewise the film documents the persistent spirit of the people, who have not been beaten by the brutalities of the National Guard.

Huezo and her fine cameraman Ernesto Pardo and assistant editors Paulina del Paso and Lucrecia Gutierrez have woven a poem out of the vivid recollections and self expression of seven witnesses, young and old, of the civil war years. The images show them doing things, while their voices are heard. Huezo revels in the sheer joy of collecting images and sequencing them, building up a narrative, a picture, that flows as naturally as the seasons, from a rider on a bicycle to men exploring a cave where they lived with six families for three years hiding from the national guard, to the mother whose young daughter joined the rebels and then was taken away and brutally killed. She coaxes her hen to nurse eggs she buys in the town into chicks. One man is a great reader, who meditates and studies and writes notes. Of the two in the cave the son stayed behind when the guards found them, walking deeper and deeper in among the bats, horrified at being caught as the others were and equally horrified at what fate might await them. The older man was taken to be hanged. Evidently somehow he survived.

The mother compares her daughter to a lightning bug. She was a light. She may survive there as a lightning bug. They are content now, she and the spirit of her daughter, she says, now that she is back in the village. When they all left to hide in the forest or were killed and the village fell off the official maps, the frogs remained. Now there are cows, and the film ends with the birth of a calf to a cow owned by one of the witnesses. And then the rains come, and he walks through the streets with a joyful smile. Thus the film shows the durability of the human spirit. These people carry their traumas with them all the time, but they have prevailed and the spirit of the village has been reborn.

Watching this film is a profound experience and an aesthetic pleasure. Tatiana Huezo is a most gifted filmmaker. In his review of The Tiniest Place for Variety, Robert Koehler, who calls the film "sublime," writes, "The subject of the Central American wars of recent decades have rarely received such a level of artistic treatment onscreen... The result is one of the most impressive debuts by a Mexican filmmaker since Carlos Reygadas' 'Japon,' both linked by an audacious embrace of cinema's power to prompt the deepest thoughts and feelings." Koehler points out that Heuzo trained at Barcelona's Pompeu Fabra school of nonfiction filmmaking, "whose tradition of poetic images and rich textures is vividly on display here," but he also remarks that the film is very much of its place and very much a personal statement, the filmmaker's own grandmother being from Cinquera.

Besides the eloquent speakers and the rich ambient sound (including frogs, livestock, bats, and insects), there is singing by an old lady, the music of a youthful marching band, and an understated score by Leonardo Heilblum and Jacobo Lieberman.

This film is many things: gorgeous, supple cinematography; amazing interviews in which all the speakers become eloquent beyond a documentarian's wildest dreams; a brilliant overall conception and sense of the place and its history and its people; and editing that paints fluently and joyously -- reveling in its sheer natural mastery of cinematic technique -- with all this material to create a rich and living portrait. Anyone who wants to see all that documentary filmmaking can be at its best must seek out the remarkable The Tiniest Place.

El lugar mas pequeño seems destined for an illustrious history that is just beginning. It was shown at the Festival Ambulante at Mexico City in February 2011 and its first Stateside showing and international premiere is at the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review.

SFIFF Screenings

Sat, Apr 30 6:00 / PFA

Sun, May 1 4:15 / Kabuki

Thu, May 5 5:45 / Kabuki

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:15 PM.

-

Kelly Duane, Katie Galloway: Better This World (2011)

Kelly Duane, Katie Galloway: Better This World (2011)

BRAD CROWDER AND DAVID MCKAY IN BETTER THIS WORLD

FBI informant case against two young political demonstrators with an intricate aftermath

Katie Galloway and Kelly Duane de la Vega's Better This World is a documentary about two protesters at the 2008 Saint Paul, Minnesota Republican National Convention and the machinations that took place and personal moral dilemmas that arose for them after their arrest. It was shown at the Austin, Texas SXSW festival and picked up by the San Francisco International Film Festival. A TV release on the PBS show "POV" makes its theatrical distribution unlikely, but students of US politics will want to watch it in some form.

The FBI and other government security agencies assumed that there was a 100% chance of a "catastrophic" terrorist attack occurring at the convention. Brad Crowder and David McKay, two childhood friends from Midland, Texas in their early twenties, came to the Twin Cities to disrupt the proceedings by violent means. Midland, incidentally, is the hometown of George and Laura Bush, so a sign at the border of town proclaims. Brad was the more political, and he politicized David. In prison interviews, excerpts from which run through the film, Brad, though younger-looking and less burly, is clearly the more articulate, intellectually energetic of the pair. It's not clear that David understood the seriousness of the RNC disruption plan. But his awareness grew in prison.

Brad's and David's mentor became Brandon Darby, a leader of the grassroots organizing program Common Ground Relief who fought extensively for the rights and needs of Katrina victims in New Orleans. After a kind of recruitment rally in Austin, Brandon Darby met with Brad and David and another young man planning on going to the RNC. He played the bad-ass, challenging and taunting them a bit. But in the weeks following Darby worked closely with the two and others planning to come up from Texas to disrupt the RNC in Minnesota. When the little group got to the Twin Cities, the police and FBI had already mounted a vast operation of repression with raids and arrests, and they followed Bradley and the others and stopped them. Later their van was broken into and gutted of all its contents, including shields Darby had made for protesters. This apparently led Brad and David to think about violence: they bought the makings of homemade bombs at a Walmart. We see surveillance camera images of this.

(Warning: don't read beyond here if you want to be surprised by the story the film tells. )

Then, when Brad and David were arrested at a demonstration with Molotov cocktails which they had not really decided to use but had no time to dispose of, it emerged that Brandon Darby had been an informant for the feds for the 18 months leading up to the convention. He instigated them and then betrayed them.

Brad was held because he had no ID but David was released. Brandon kept track of him for the FBI, which raided where David was staying in the early morning and took him. Later, Brad took a plea bargain on possession of two years. The feds had sought David's cooperation against Brad and not gotten it, and David chose to go to trial, a dangerous move indeed. Thus the two were pitted against each other in a case where both had been entrapped and instigated to perform an act that they would probably not have performed. They were about to leave Minnesota, and assembling the gasoline-in-a-bottle firebombs was a gesture that they had little or no motivation on following through with. What follows in the story is a complicated tale of more plea bargaining and federal manipulation of the two defendants. The film shows where they are now and what has become of Brandon Darby, who evidently was always a very confused and dangerous man.

The film is sharply assembled, with an amazing array of archival material, surveillance shots, calls from the prison by David to his father and girlfriend, Brandon Darby's cell phone remarks to his FBI handler, cell phone images of the riots showing the principals involved, many moments of Darby speaking, a police raid (presumably simulated), and so on, along with enlargements of text messages and transcripts. Also key are interviews with lawyers on both sides of the David McKay trial, and a member of the jury, who explains the dubiousness of choosing Darby as an FBI informant -- seriously undermined the federal case against David and leading to a hung jury. That was not the end of it, for him or for Brad. However Brad served his plea-bargain two years, having narrowly escaped an upgrade of his sentence, and is out of jail and a political activist. The filmmakers had such access, they can even film David at a bar thereafter with his girlfriend discussing his legal options. Sometimes this seems like reality television, though of a high order and with much to think about concerning the perils of being a dissident in post 9/11 America.

Better This World premiered at SXSF in Austin, and has been included in Boston and Sarasota festivals. It was also part of the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review. It is one of a number of strong and varied non-fiction flims at SFIFF 2011, which include: The Arbor, The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceauşescu, Black Power Mixtape, Foreign Parts (seen but not reviewed), Le Quattro Volte, Something Ventured, and the exceptional The Tiniest Place.

SFIFF Screenings

Sat, Apr 23 6:00 / Kabuki

Tue, Apr 26 6:30 / PFA

Fri, Apr 29 9:30 / Kabuki

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:18 PM.

-

Alison Bagnall: The Dish and the Spoon (2011)

Alison Bagnall: The Dish and the Spoon (2011)

GRETA GERWIG AND OLLY ALEXANDER IN THE DISH AND THE SPOON

Fuming and flirting in Delaware

In sometime-writer Alison Bagnall's sophomore effort as a director, we are instantly thrown in with Rose (Greta Gerwig), who's angry and weepy and guzzling beer from bottles as she leaves New York in a Mercedes station wagon to escape from her husband, who's just slept with another woman. This we learn from the frequent angry calls Rose makes to him on pay phones. She's wearing a shabby overcoat over pajamas and has forgotten to bring her wallet. Out of pity a roadside shopkeeper lets her have a six-pack and some snacks for the spare change she finds in the ashtray.

In a lighthouse tower Rose finds and rescues a shivering British waif, a striking-looking Boy (she never asks his name) played by up-and-comer Olly Alexander -- he had a role in Gaspar Noë's Enter the Void and before that played Keats's (i.e. Ben Whishaw's) younger brother in Bright Star. Alexander has a nice accent, Bob Dylan hair, and the face of an angel. Gerwig is luminous herself, even in deshabille: Rose and Boy could be siblings. Initially she just wants to dump him somewhere, but he's sweet, cute, and unthreatening and she needs company. Rose winds up taking Boy (who says he came to America for a girlfriend who instantly dumped him) to her apparent destination -- so far as she has one -- her parents' summer house located in a boarded up Delaware beach town. It's winter and the cold and desolation make this desultory two-hander cozier and more romantic, so far as there is a romance.

It turns out the Other Woman is actually in town, and Rose is here to "kill the bitch." An admirable aim, no doubt, but first she must find her. She is no longer working at a beer bottling plant, which Rose and Boy visit, nicking bottles and getting drunk under a table. Rose's flirtation with the very young Boy (he looks about 17, though Olly is more like 20) leads him to fall for her. "I could marry you," he declares in the fireplace-heated living room of the summer house after they have exchanged fake alternate back stories and cuddles. He admits he's estranged from his father in England but accepts the money his dad sends every month. His wallet is stuffed with cash and Rose sends him upstairs to fetch her coat and steals a wad of his money.

That's but one example of how carelessly Rose uses Boy. He's no more than a distraction on her "fugue" (as the French might call her ramble) while she simmers down, waits for an apology from her husband (which comes), and has a chance to attack the "bitch" at an Eighteenth Century Country Dancing class she drags Boy to in costume. This whole sequence is awkwardly handled -- of several signs Alison Bagnall doesn't altogether know what she's doing. Another is the way the film, so fresh-feeling at the outset, begins to stall and become repetitions. A sequence when Rose and Boy put on Victorian clothes and have a staged "wedding" picture taken goes nowhere. Dish is over before it's over.

The leads carry us most of the way, however. Challenged more than usual emotionally here, at least when on the pay phone, Gerwig is even more a rising star than Olly. Her graduation from mumblecore to mainstream is proven by recent roles in Greenberg, No Strings Attached, and Arthur. The Dish and the Spoon is a low-budget film -- Bagnall couldn't afford to meet in person with her L.A. editor (whose services were sorely needed). But this isn't exactly mumblecore: images and dialogue are too clearcut for that. Some degree of charm hovers over the wistful romance, thanks to Olly and Greta. Since the intervals between her rants sometimes take on an edge of comedy nothing gets too serious, and Boy's infatuation steers just this side of saccharine. Adam Rothenberg is solid briefly as the husband, when Rose drives home and for the inevitable reconciliation and drops off poor Boy in the backyard. He leaves her a thoughtful gift-wrapped offering (a silver cup and spoon, no dish) and returns to life as a wandering British waif.

Music, some of it provided by Olly, who plays keyboards and sings, is kept unobtrusive. Olly even draws a skillful portrait of Rose in the sand. The cinematography by Mark Schwartzbard, simple HD, is handsome, though it relies a bit much on shots with orange sunsets creeping in.

The Dish and the Spoon debuted at the SXSW festival in Austin. It was also presented a month later at the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review.

SFIFF Screenings

Thu, Apr 28 8:45 / PFA

Fri, Apr 29 6:30 / Kabuki

Sun, May 1 3:30 / Kabuki

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:21 PM.

-

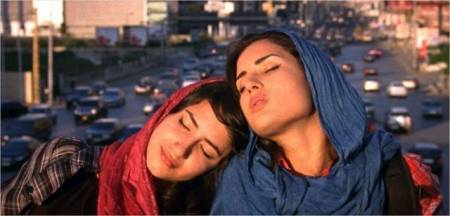

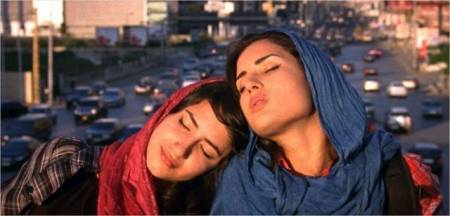

Maryam Keshavarz: Circumstance (2011)

Preview

Maryam Keshavarz: Circumstance (2011)

NIKOHL BOOSHERI AND SARAH KAZEMI IN CIRCUMSTANCE]

Bad girls and a warped brother in Teheran

With Circumstance (Sharāyit) Iranian-American first-time director Maryam Keshavarz has provided an extraordinarily bold picture of the Teheran middle class (particularly a young gay minority) in revolt against Islamist repression. No one unwilling to burn bridges or unable to work outside Iran could have painted such a vivid picture (main cast members have two passports and most of the shooting was done in Lebanon). Too bad the young director's excitement over the lesbian love story of two high school girls and her fondness for pointless jump cuts in place of narrative links lead to excess and incoherence. It's often not clear whether the youthful indiscretions so vividly, not to say luridly, depicted, reflect a spirit of defiance, or sheer delight in what, in the culture at large is now seen and felt as depravity. This is a crucial distinction that is not clearly made. The frequent make-out scenes between Atafeh (Nikohl Boosheri) and Shireen (Sarah Kazemy), some real and some imagined by one of them in luxuriously tacky Dubai nightclub or hotel settings, tend to veer into soft-core lesbian porn. The shock is the greater because, despite the international background of the cast and director, the film feels quite Iranian.

Keshavarz was born in the US but as she describes it has been back and forth to Iran her whole life. Her education is mostly American but also international. She studied comparative literature and near eastern studies at Northwestern and Michigan before taking an MFA in directing at NYU. She has made a documentary and a couple of prize-winning shorts. She has also taught at the University of Shiraz and studied Latin American literature in Argentina, where one of her shorts is set. In interviews Keshavarz has said Circumstance seems to strike familiar cords in people from many countries. However the film really stands out primarily as a racy depiction of the craziness and repression of Iran under the Mullahs. (As Robert Kohler points out in his Variety review, Circumstance's risqué content makes it "ineligible at most Mideast fests, but will set tongues wagging in the widespread Iranian diaspora community, where the pic is already a talking point.") In a beach scene men in Speedos sit around picnicking with women completely shrouded in black. Atafeh and Shireen go to parties and whip off their shawls revealing tight, shimmering, sexy dresses underneath, entering a scene where T-shirted men dance to rap, gay mixing with straight. he girls drink. They smoke. They curse the regime in the most vulgar and unladylike terms..

Circumstance debuted at Sundance in January 2011, winning the audience award, and received various grants besides being supported by Sundance workshop. It was shown at New Directors/New Films in New York in early April and at the SFIFF in early May. It was screened and reviewed at the San Francisco International Film Festival. It is scheduled for US release August 19, 2011.

SFIFF Screenings

Sun, May 1

6:00 / Kabuki

Tue, May 3

6:15 / Kabuki

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:24 PM.

-

Takashi Miike: 13 Assassins (2010)

Takashi Miike: 13 Assassins (2010)

A tour de force battle sequence leading to the defeat of a sadistic villain

It's hard to decide. In 13 Assassins is Takeshi Miike transcending the noble but depleted tradition of samurai films in his own way, or is he simply debasing that tradition in the general contemporary way, draining it of nobility and personality and turning it into a blood-fest? The long final battle sequence, in any case, is so ridiculously watchable that it justifies a film otherwise less bold than Miike's previous celebrations of gore. It is tempting to compare this with Kurosawa's war epic Seven Samurai -- but better not to. Miike is no Kurosawa, and isn't trying to be, except that the traditions of samurai epic are the basis for 13 Assassins' basic machinery. Miike's actual source is a less illustrious film of the same title from 1963 by Eiichi Kudo.

Miike sets his standard of violence with the first sequence, which is probably the most vividly graphic scene of ritual harakiri on film. You don't actually see the guts flow, but the camera presses in upon the face of the suicide following the grunts and groans of each horrific stroke of the blade. This suicide signals that there has been a humiliation, and in slow, old-fashioned scenes that follow there comes the elaborate explanation. A very high placed and very evil man who may become Shogun is wreaking havoc in the land. He must be stopped, and a few good men are chosen by Sogun official Sir Doi (Mikijiro Hira) to do the job.

It's 1844. The evil man is Lord Naritsugu (Goro Inagaki), and some of his atrocities are shown, including his penchant for chopping off heads (and, later, for kicking the severed heads around on the ground). His sadistic cruelty is not left to the imagination. There is also a horrifying scene of a scrawny naked woman who has had her arms lopped off and her tongue cut out. The noble samurai Shinzaemon Shimada (Koji Yakusho) is the one chosen to assassinate Lord Naritsugu. It's going to be a tough job, because Naritsugu moves around with a small army to protect him. When the big day comes, he arrives with 200 men instead of the 70 the samurai band was expecting. The 13 have an advantage, though -- which adds a somewhat gimmicky element to the film. Shinzaemon has been authorized to buy out a whole village, which he and his men have rigged as a collection of booby traps. Elaborate Rube Goldberg barriers are poised to appear when activated, cutting off groups of Naritsugu's men; and explosives have been planted all over to kill Noritsugu's men or to cut them off in surprise cul-de-sacs.

This leads to an outrageously tricky but also curiously satisfying battle sequence that proceeds seamlessly, with a few much-needed pauses, for around 45 minutes, or a very large chunk of the two-hour film. To add color there are several notable individuals. These include the handsome Shinrouko (Takayuki Yamada), Shinzaemon's right-hand man; a cute teenager, Ogura (Masataka Kubota), who is as brave and ready to die as the best of the more seasoned samurai; and the crazy mountain man Koyata (Yûsuke Iseya), not a samurai at all and added at the last minute, but both indifferent to traditions and status and superhumanly brave and adept at killing. Koyata has just about the last word, and scampers off through the carnage eager to try some new occupation, such as being a thief or going to America and sleeping with a lot of women.

The battle sequence is a technical marvel: so much vivid and clear sword fighting, interwoven with so many intricate and implausible sequences involving the samurai's system of traps built in the village, as well as some bold and highly successful archery by the 13, some incendiary bulls, and Koyata using a ball and sling, large branches, and anything else he can get his hands on to wipe out the opposition. And then, after a lot of the evil nobleman's hired guards have been cut down and nearly all of the 13, the proceedings turn to the the "elegant" focus (Lord Naritsugu's word) on "one-on-one." Eventually the classic Western finale: two men kill each other, and the sadist writhes pitifully in the mud, first complaining of the pain, then thanking his assassin for giving him the most interesting day of his life. A nice mixture of the pathetic and the novel, there. For all this, the film is worth watching, and required viewing for samurai movie fans. Apart from the nastiness in the opening sequences, those are conventional and even a bit clunky. But the fighting is amazing. It's just lacking in the epic context and the rich sense of narrative structure you find in Seven Samurai , not to mention many a good Western.

Miike's 13 Assassins screened at Venice, Toronto, and London in 2010, and at SXSW in 2010, followed by the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was shown May 1, 1011. It opened theatrically April 29 in the US and May 6 in the UK. Seen for this review at the IFC Center, New York. It will be rolling out in release in the US in May, June, and July as listed here.

Miike's second samurai film, Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai in 3D, is a selection at the 2011 Cannes festival (11-22 May).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:27 PM.

-

Werner Herzog: Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010)

Werner Herzog: Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010)

DRAWINGS IN THE CAVE OF CHAUVET-PONT-D'ARC

Dreams you will never understand

The ancient cave drawings are a mystery, and that's why Werner Herzog was the man to make a film about them. The Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave, in the Ardèche, in southern France, contains the most ancient drawings of all, and this is where Herzog and his small crew were given access to go in during a short period when scientists and specialists are allowed in. They had to carry small, light cameras and lights operated from batteries attached to their waists, and they could touch nothing. They could walk only on narrow metal trestles down the center of the cave's chambers.

Whose are the "dreams" in the film's title? Are they Herzog's, the Cro-Magnon artist-shamans', or those of the contemporary archeologists whose work is to document and explore Chauvet and try to tease out its secrets and meanings? Herzog talks to a young Frenchman who confesses he used to do something else. He was a juggler in a circus. Then he visited a cave and the drawings gave him dreams, of real lions and drawn ones, dreams so vivid he quit the circus and studied archaeology. Maybe Herzog is thinking of this young man's dreams in his title.

The film is in 3D to convey the interior spaces of the cave -- strange, rich spaces, with translucent stalactites and stalagmites and sparkly surfaces (many of which came after the drawings were made). The drawings are not on flat spaces, though some of the French experts speak of them being in "panels," which makes them sound flat. "The most common themes in cave paintings are large wild animals," the Wikipedia article, "Cave Painting," tells us, "such as bison, horses, aurochs, and deer, and tracings of human hands as well as abstract patterns, called finger flutings." The drawings have a famous sureness and fluency. They also seem to use multiple overlapping images and multiple legs of animals to convey movement -- the first motion pictures, Herzog says. The drawings tell us more than archaeological remains, in some cases, about the animals that roamed the land freely -- a cold, dry land, with glaciers.

The cave is beautiful and haunting; the drawings are unusually large, numerous, and striking. Be quiet now and listen to the sound of the cave, one of the guides says. And Herzog says they began to feel a presence or presences so powerful the cave became oppressive, and it was a relief then to come back out. Chauvet is very deep in and protected, found only in the early 1990's, because a great wall of stone fell down and closed it in, and this is why it is so unspoiled, and why access to it is severely restricted to preserve it.

There's something about this place you can't get your head around. And that something Herzog -- whose voiceover, as always in his documentaries, for good or ill dominates the film -- states right way in the first few moments of the film: these drawings are 32,000 years old. Though Herzog doesn't mention this, some challenge this figure, saying they are too sophisticated to go back that far. But no matter. They are still tens of thousands of years old. And think about that. In films we are fed doomsday sci-fi stories all the time in which Armageddon arrives twenty of fifty or a hundred years from now. But man -- Homo Sapiens, or in this case Homo Artisticus, or perhaps, as one French archeologist suggests, Homo Spiritualis, goes back 32,000 years. We can't even imagine man going forward one thousand. The mystery of the past is far richer than the mystery of the future. Why don't we have more imagination, and more hope?

Herzog has made a remarkable film about an extraordinary subject. But I confess to finding Cave of Forgotten Dreams frustrating and a little disappointing. The spaces seem inhospitable, and would be even if there were free, unlimited access. Aesthetically, the visuals are unsatisfying. Too often the images are seen only partially, in flickering light. Or some French lady lecturing us about the drawings is standing in between the camera and the drawing so we can't see all of it. It is better to page through one of the lavish books that have been published showing the drawings at Lascaux, which are similar, if later (perhaps much later: estimated to be 17,300 years old), and seem, in the photographs, to be more beautiful, more colorful, with shades of brown and sienna and black, while the Chauvet drawings are apparently done in charcoal and are more monochromatic. (There are said to be red ones and black ones, but this is not clear from the film.)

Is 3D a help or a hindrance? One might appreciate the drawings more as drawings and for their conception flattened out, as in the Lascaux books, instead of having their bumps and declivities emphasized. Moreover 3D remains a crude device, no better than my grandmother's Stereopticon, a jerky and distracting attempt to imitate real depth. And as for the sound, though there's a charming and deliciously silly moment when one of the French experts plays the "Star Spangled Banner" on a reconstructed Cro-Magon flute, Herzog relies on a lot of loud string-heavy New-Agey music that is particularly intrusive toward the end when we should be getting deep into the drawings and instead are distracted from them.

We know people didn't live in the caves. Bears did, and they left their paw and nesting marks in the soft loam of the cave floor. We don't know what the drawings were for or who did them. They might have been done by adolescents (not mentioned here), and many may have been done by women (also not mentioned). They may have been done to evoke powerful spirits, or make the animals multiply ("hunting magic"). They may have been done by shamans in trance states. Not much is said about all this in the film. Herzog likes to dwell on the mystery. Here in the Cro-Magnon caves he finds the same unknowable and unnameable quality that he sees in his scary version of Nature. He may prefer not to dwell on possible solutions. And he may be right there. But he could have told us more about what the hypotheses about the cave drawings are -- and skipped the mutant albino alligators he works in at the end. But then it wouldn't have been a Werner Herzog movie, would it?

Werner Herzog's Cave of Forgotten Dreams was introduced at Toronto in September 2010 and shown at other film festivals in 2011, including SXSW and San Francisco. It opened at IFC Center in New York April 29, 2011.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-04-2015 at 11:29 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks