-

Film Comments Selects And New Directors/New Films 2010

LINK INDEX FOR CK REVIEWS OF THESE TWO SERIES:

Amer (Hélène Cattani and Bruno Forzani 2009)--ND/NF

Be Wise (Juliette Garcias 2010)--FCS

Beautiful Darling (James Raisin 2010)--ND/NF

Bill Cunningham New York (Richard Press 2010)

Down Terrace (Ben Wheatley (2009)--ND/NF

Father of My Children, The (Mia Hansen-Løve 2009)-ND/NF

Green Zone (Paul Greengrass 2010)--FCS

How I Ended This Summer (Alexei Popogrebsky 2010)--ND/NF

Hunting & Sons (Sander Burger 2009)--ND/NF

I Killed My Mother (Xavier Dolan 2009)--ND.NF

Last Train Home (Lixin Fan 2009--ND/NF

Like You Know It All (Hong Sang-Soo 2009)--FCS

Man Next Door, The (Mariano Cohn, Gastón Duprat 2010)--ND/NF

Night Catches Us (Tanya Hamilton 2101)--ND/NF

Oath, The (Laura Poitras 2010)--ND/NF

Persecution (Patrice Chéreau 2009)--FCS

Red Chapel (Mads Brügger 2009)--ND.NF

Tehroun (Nader T. Homayroun 2009--ND/NF

The Film Society of Lincoln Center has three important film series at this time of year:

Film Comment Selects: February 19 – March 4, 2010

Rendez-Vous with French Cinema: March 11-21, 2010

New Directors/New Films: March 24–April 4, 2010

In this thread again this year I will be reporting on some selections from FCS and ND/NF.

I have reviewed all selections of the Rendez-Vous in another thread.

To go to the Forum comments thread for FCS and ND/NF 2010 go here.

I've seen six of the Film Comment Selects series and will report on them briefly. The FSLC page for this series is here.

The FCS films I have watched are:

Persecution (Patrice Chéreau 2009)

Be Good/Sois sage (Juliette Garcias 2009)

Kinatay (Brillante Mendoza 2009)

Like You Know It All (Hong Sang-so 2009)

Happy End/Les derniers jours du monde (Armand and Jean-Marie Larrieu 2009)

The Time That Remains (Elia Suleiman 2009)

Green Zone (Paul Greengrass 2010)

I will attend some of the press screenings of New Directors/New Films and will report on them. They begin March 8, 2010. The list of films in the series and schedule of public screenings will be found here.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-06-2010 at 12:42 AM.

-

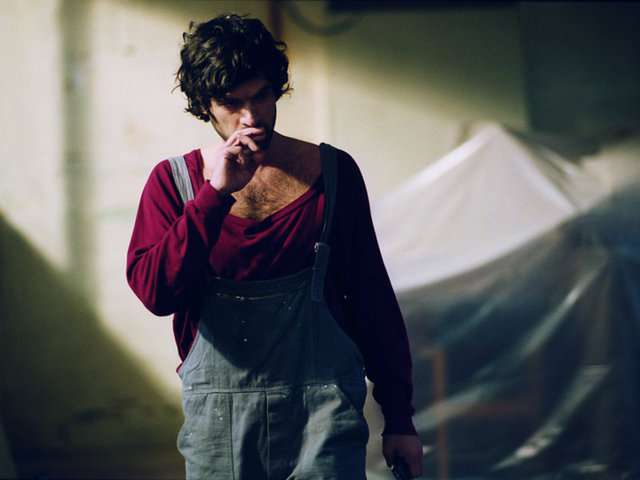

Patrice Chéreau: Persecution (2009)--FCS

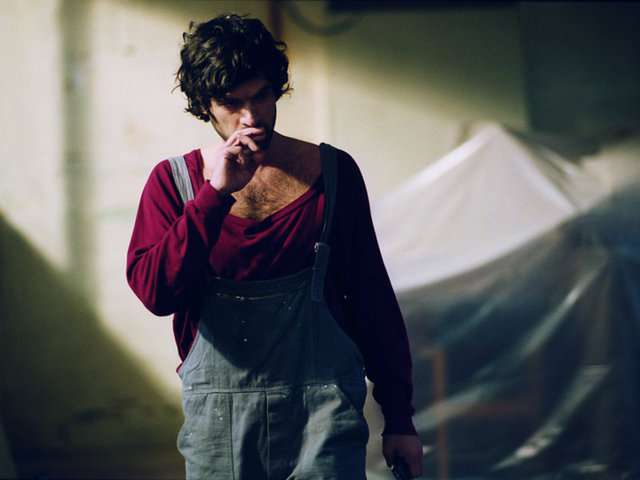

ROMAIN DURIS IN PERSECUTION. ANGST AT THE WORK SITE. BUT OVER WHAT?

(From the Film Comment Selects series.)

Talking and agonizing

Patraice Chéreau's disappointing new melodrama could be called Three Characters in Search of a Neurosis. Or perhaps the love-sick stalker played by Jean-Hugues Anglade has found his. Actually, though we don't know why, he's nuts; his character's name in the credits is simply "Le Fou," the crazy person. In a way Sonia's (Charlotte Gainsbourg's) character has found hers too: her neurosis is simply the protagonist, Daniel (Romain Duris). Trying to put up with Daniel's moods and pretending their relationship with such a self-absorbed drama queen has a future could be causing her to implode.

But what about Daniel? Daniel is a young man whose dramas have no discernible external motivation. He's disheveled in a fashionable, good-looking sort of way. He wanders between two construction sites, large rehab spaces actually, providing a spacious Parisian background for his rants, as well as a cool, if provisional, pad. As Daniel, Romain Duris does a lot of brow-wrinkling and complaining, as he does with more success in Dans Paris and The Beat My Heart Skipped, two other dramatic milestones for this actor that provided more of an objective correlative for his torments. But exactly what's bugging his character this time is not cleared up by the screenplay penned by Chéreau in collaboration with Anne-Louise Trividic (whom he worked with more successfully for his three previous films, Intimacy (2001), Son Frère (203), and Gabrielle (2005). All we know is that Daniel and Sonia are both emotionally drained and insecure.

The feel of the action is appropriately operatic (and its images handsomely chiaroscuro) for a director who's successfully staged so many actual operas, but these arias aren't worth listening to. Unfortunately Persecution illustrates too well the assertion of a friend of mine that French films consist of nothing but people talking. They talk about their relationship, they meet and part, meet again and talk some more, and they go to cafés and talk. There are some well-known actors in the café, with minor roles, including Gilles Cohen, Alex Descas, and Hiam Abbass. Some never get to say anything -- because the principals do so much talking, they're not needed, it would seem. Nothing much is happening except that Daniel feels he's not up to maintaining his relationship with Sonia. This is in spite of the fact that Sonia's work (whose nature is never specified) requires her to be frequently out of the country, and when she's back, they mostly just talk. This difficulty is compounded when "Le Fou" starts showing up with increasing frequency, doggedly pursuing (or persecuting?) Daniel and declaring his (mad) love, which nothing, even being beaten up by Daniel, can stop, and which nothing explains.

When Sonia's in town, Daniel is at her place two or three times a week, but always with the recriminations and suspicion on his part. And the narcissism, which is the less appealing since he appears to have no talent or consuming project to justify self-absorption. Eventually Sonia also begins to acknowledge that her relationship with Daniel is doomed. So you could also call this film The End of an Affair, or The Decline of a Relationship. Granted those titles are taken, or dull; Persecution piques the curiosity more, even if it's somewhat inaccurate, unless you conclude that the Crazy Person played by Anglade is "persecuting" Daniel by constantly turning up wherever he goes, even invading his temporary living space. But the Crazy Person seems more like a device than a person.

There is an irony about this emotionally unconvincing device of Le Fou, because Anglade's first lead role in a feature film was as the youth in Chéreau's haunting 1983 drama of sexual obsession, The Wounded Man/L'homme blessé. In L'homme blessé Anglade's character is a teenage boy still living with his parents who, impulsively running out to a nearby train station one night, for the first time acts upon powerful homosexual desires that lead him to pursue a dangerous older man. Here, he's the older man, but still doing the pursuing. Only this time the film doesn't get inside his psyche, and his obsession seems more like an annoyance (for its object) than a troubling and irresistible impulse.

Leslie Felperin points out in his Variety review of this film that Persection's theme mimics that of Ian McEwan's novel, Enduring Love, also made into a movie, of a man whose strained relationship with a woman becomes even more tormenting when he starts being stalked by a mad would-be male lover. The circumstances of meeting of the two men are shifted from a balloon accident to a meeting in a Metro station. However the Chéreau-Trividic writing team lack McEwan's knack for snappy plotting and Persecution never seems like it's going anywhere, and never really does.

Nothing can take away from the intensity of The Wounded Man, the dark beauty of La reine Margot, or the emotion of Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train or Son frère; and even if its audience has been limited, Gabrielle is a magnificent film. But despite some good moments and dedicated efforts from the actors, Chéreau is running on empty here. Maybe the gifted and charismatic Anglade, Duris, and Gainsbourg are exhausted too; maybe they should take a break from neurosis and go back to comedy for a bit.

Persécution opened December 9, 2009 in Paris with generally good, but some doubting, reviews (Allociné average score 2.0, points 51). Shown at the Walter Reade Theater, Lincoln Center, as part of the FSLC Film Comment Selects series in February 2010. You'll find more detail, and more sympathy, in Mike Goodridge's review in Screen Daily.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-11-2010 at 03:18 PM.

-

Juliette Garcias: Be Wise (2010)--FCS

ANAIS DEMOUSTIER AND BRUNO TODESCHINI IN BE WISE

Juliette Garcias: Be Wise (2010)--FCS

Soft hints and portents

Shown as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center Film Comment Selects, Be Wise/Soi sage maintains the series' reputation for blending elegance and edginess. Juliette Garcia's first feature, shown in February in FCS, scheduled for mid-April April release in France, is beautiful-looking, very quiet -- thoroughly weird. The fine camerawork is set off by silence, the rustle of trees, and piano passages. There's something hypnotic about the film and, eventually, disquieting.

The focus is on a rather distant young woman called Nathalie, who's taken a summer job at a remote village as a baker's delivery person. She tells everyone here her name is Eve, and for good reason. She doesn't want her presence yet to be known to Jean, a pianist and a married man with whom she has had an affair, who lives here.

A Zen-like calm pervades the early sequences of Be Wise/Sois sage. Natalie/Eve watches the young baker kneading bread. The camera seems to move silently through a green shade, like a stalker -- which is what Eve in a sense is. The quiet doesn't seem artificial. It fits with the stillness of a region that's warm and verdant but sparsely populated. Eve's job, which she plunges into without needing guidance, is to drive a small panel truck around the countryside delivering various-shaped loaves of the bakery's products to local households and collect money for them. The French dedication to making freshly baked artisanal bread available at all hours appears to be alive and well.

Anaïs Demoustier, the young but very assured actress who plays Nathalie/Eve, has the right kind of face, enigmatic, seeming to hide secret knowledge. She is both girlish and womanly. She lurks. She reveals nothing. She's friendly, but when approached, she pulls back. That goes for any men she encounters. She gives them a come-hither look, or even spends time with a young stranger by a river, but when approached, says she has a boyfriend. She keeps telling lies, which don't cohere, except to tell us that she's haunted. Sometimes we hear piano music. We get glimpses of Jean's life, and we see two sets of hands on a keyboard without knowing whose they are. Other characters emerge, people Eve gets to know doing her job.

That job seems to give her ready access to people's properties and houses. She walks up to them when they're asleep. She acquires an instant intimacy, without ceasing to be enigmatic. Without Jean's prior knowledge, even after he has run into her, she babysits his child. Already she has come to seem haunted and strange. It's never fully certain what the relationship was, but it appears to be something not at all normal. Garcias' style is extremely suspenseful, the mood verges on the horror genre, yet the effect is quite individual. Uncertainties that remain at the end seem quite calculated. This is a mood piece and a think piece that blends bizarre sexuality, obsession, and pastoral reverie. This is Fatal Attraction filtered through the sensibility of Catherine Breillat, done in a third style that we're now discovering.

Be Wise may not be for the general audience because it defeats genre expectations. Its slow, at times almost glacial, pace requires patience and won't work unless you give yourself up fully to the visuals. But these are lush. Indeed the film's beauty and self-assurance, despite its oddity, may point to US art house release. It's certainly an original and promising piece of work with a feminine point of view and it makes skillful use of image, ambient sound, and location to build its mood.

-

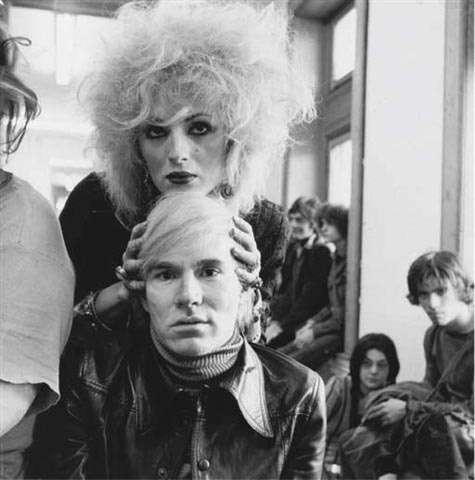

James Raisin: Beautiful Darling (2010)--ND/NF

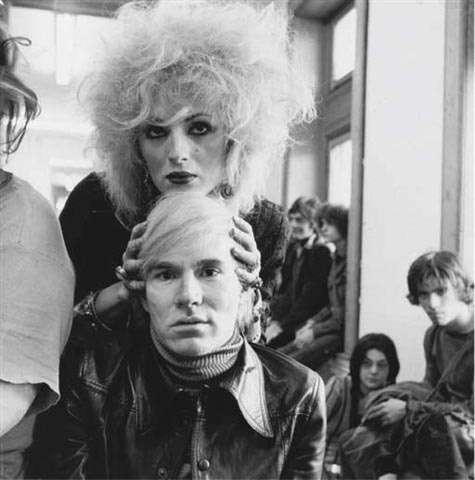

CANDY DARLING WITH ANDY WARHOL IN A VINTAGE PHOTO AT THE FACTORY

James Raisin: Beautiful Darling (2010)

Take a walk on the wild side

Edie Sedgwick, Andy's druggie socialite "muse," and a real girl, was dead by 1971. Among the "chicks with dicks" who gathered at the second, Union Square version of Andy Warhol's Factory, Candy Darling was the most ethereal and beautiful and pure, it seems from this documentary, which recounts her short life. She died of lymphatic cancer before reaching the age of thirty, already by then cast off by Andy, who used Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis in later films. One of the many photographers who lensed her, Peter Hujar did a glamorous portrait of Candy on her hospital deathbed, garlanded with roses and still perfectly made up.

This documentary's existence is due to the devotion of Candy Darling's closest male friend, Jeremiah Newton, prominently featured and also a producer. He still carries the flame, and Beautiful Darling is book-ended by his arranging for Candy's ashes to be buried along with his (Jeremiah's) mother's, under a tombstone for them and, when his time comes, Jeremiah himself. Back in the day, he attached himself to Candy Darling when he was only sixteen and when she had a preferred place in Andy's Factory and the Factory hangout, Max's Kansas City.

Newton approached James Raisin (who's made films about the Beats and written stuff about Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith and a screenplay for Abel Ferrara about Warhol) with piles of memorabilia about Candy and interview tapes he made right after her death with people who knew her. He also had archival film footage. Raisin has woven together all these records and his own recent interviews with some germane and often pungent talking heads, including Fran Lebowitz, Glenn O'Brien, Taylor Mead, Bob Colacello, John Waters, Gerald Malanga, Paul Morrissey, Holly Woodlawn, Pat Hackett, George Abagnalo, and Sam Green, among others, to make Beautiful Darling an excellent record of the person and the context and another valid entry in the collection of cinematic Warholobilia. There is lots of good and appropriate music, and for readings of letters and statements, Chloe Sevigny does the voice of Candy Darling.

She was originally Jimmy or James Slattery, and as we're told in Lou Reed's famous song "Walk on the Wild Side," which describes the "chick with dicks" Andy used and threw away, "Candy came from out on the Island," Long Island, that is, from a flat monotonous development in Forest Hills. Candy came from out on the Island/In the backroom she was everybody's darlin'/But she never lost her head/Even when she was giving head/She says, Hey babe/Take a walk on the wild side/I Said, Hey baby/Take a walk on the wild side/And the coloured girls go/Doo do doo do doo do do doo...'

While Edie Sedgwick was born a real girl, Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling, and Jackie Curtis were among the various trannies who gathered at the Factory. 'Take a walk on the wild side' was a come-on to prospective johns, meaning, Have sex with a transvestite prostitute. But what we learn from Beautiful Darling is that the Warhol Factory girls weren't all alike.

None of them worked harder at being a girl than Candy, but not just at being a girl -- at being glamorous and beautiful, inspired by memories of Forties screen divas seen in TV movies and dreams of Hollywood fame. She didn't always necessarily say much, except when performing somebody's lines, always in that special breathy feminine voice of the drag queen (or Marilyn). She was in Warhol's Flesh and Women in Revolt. Candy used her Warhol film fame to land other screen appearances, and Tennessee Williams, who was among her admirers, cast her in his play, Small Craft Warnings.

Warhol, in one of the clips, says he was making movies because it was easier than painting. Cross dressing, though, was not only hard work but dangerous work: back in the Sixties it was illegal in New York for a man to be on the street dressed as a woman. They could be hauled off by the cops just for wearing heavy mascara, so the trannies carried their dresses in shopping bags and slipped their gear on slowly till night came, and it was safer. (Agosto Machado tells us about this.)

Beautiful Darling shows us hints of Candy's Jimmy Slattery origins, including a still of the then boy of 14 or so stretched on a chaise longue in shorts, showing long, sleek ivory gams. It's strange to see Jeremiah, who like not a few of the former Warhol beauties, is a big limping blob of a person now, as a wraith-like androgynous beauty himself, when with Candy. But in a self-penned obit, Candy mentions poor Jeremiah way down in her list of people she loved and owed it all to.

John Waters is always a sharp voice, but Fran Lebowitz, one of the wittiest and most articulate non-writing writers of our times (and of course author of the droll Metropolitan Life, first aired as columns for Andy's Interview magazine), is the treasure here. Not just she but Andy himself says Candy should not lose the penis. She just wouldn't be the same. Apparently she and Newton were not a couple and she had no man in her life. The film ends with the line that to be true to yourself is the greatest morality. But as Lebowitz points out, a transsexual who becomes female never had a girlhood. And so Candy, though wonderfully successful at being a glamorous mirage, found it terribly hard work. Fran points out real women don't work so hard all the time. And so it is artificial, and exhausting, and Candy was ready to die of cancer. When the tumor was found, it ushered in one of her greatest roles, that of a tragic early death.

Beautiful Darling had its world premiere at the Berlinale in February 2010, showed at the BFI Lesbian and Gay Film Festival in London in March, and will be presented as part of the New Directors/New Films series of the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art, April 2, 2010 at MoMA and April 3 at the Walter Reade Theater.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-10-2010 at 07:10 AM.

-

Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani: Amer (2009) --ND/NF

Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani: Amer (2009)

Images and sound

Cattet and Forani are a Belgian couple who have made five short films together. This is their first feature. Divided into three parts, it focuses on childhood, adolescence, and womanhood in the life of Ana. Each moment is seen symbolically, very sensually, but without much discernible narrative, in a marvelous display of stylized visuals (in intensely colored and multiple-filtered 35 mm. images). There is a powerful, hit-you-over-the-head soundtrack. The material is fragmented, beginning with the images of eyes, presented in long horizontal rectangles. A girl is browbeaten by parents, or a couple anyway, whom she witnesses through a keyhole, shut in, and comes upon having sex. Later she also contemplates the hardening corpse of her dead grandfather. White grains under a bed. An ant. A spider. Loud booming sounds, which unfortunately in the Museum of Modern Art screening room blended with the underground sound of a rumbling subway line.

Later, the girl grows up and the film, which begins with dark interiors in an old house, switches to a sunny, Mediterranean, outdoor world. We are near Menton (credits indicate later), on the margin between the French and Italian Rivieras, along the Cote d'Azûr or the Amalfi Drive. A gang of motorcyclists with leather and metal and tight jeans stand by the road with their cycles. But we see only bits and pieces of them.

And this goes on and on, never ceasing to be beautiful, lushly noisy, sensual, fragmented, narrative-free. Amer, which means "bitter" in French, may be ideal for those who like to revel in "pure cinema."

There is one trouble though, and that this film tends to turn neurosis -- or desire, whatever it's about, which isn't altogether clear to me -- into a fashion shoot. It's said to mimic the style of Italian "giallo," pulp fiction, or the Daria Argento kind of stuff, and Italian movie music is among the many sonic allusions. Initially the feel is very much like something Spanish, or the Guillermo del Toro of Pan's Labyrinth. But as time goes on the impression of a fashion shoot undercuts the evocation of dream and fantasy through visual means. What might have been edgy, subtle, and memorable turns to chic kitsch. Or slick horror, when someone plays around with a straight razor in a threatening and suggestive manner as in Dali-Buñuel's Andalusion Dog.

While I and others with me found Amer hard going, despite its accomplished visuals, a British online reviewer called Alan Jones (reporting on the London Film4 Frightfest) was entranced, delighted with the evocation of Italian "gialli." He concludes, speaking of the late segment he explains is a walk along the highway to the hairdresser: "Charlotte Eugene-Guibbaud couldn’t be more tantalizing as the hair-chewing Lolita either with her mini-dress hem flapping against her knickers at crotch-level. Maria Bos is pure Florinda Bolkan in the eyes-reflected-in-knife-blade finale, the portion where debts to A LIZARD IN A WOMAN’S SKIN are felt the most. Shimmering with a lush vibrancy and utilizing recycled Ennio Morricone, Bruno Nicolai, Stelvio Cipriani and Adriano Celentano music within its superb sound design, AMER carries an erotic and exotic charge I never thought could be replicated again outside such essential gialli as STRIP NUDE FOR YOUR KILLER or the classic Dario Argento Animal Trilogy. AMER is a faultless masterpiece, so just relax and breathe in the heady perfume of Cattet and Forzani’s dazzling lady in black."

This glowing report shows the potential Amer has as a festival film that may, since Magnolia has bought it, get theatrical attention. However, in my view Cattet and Forani have not essentially moved up from their five short films to a feature, because this is merely short-film material spread out over ninety minutes, divided into three, and diced up into many edited visual fragments. A series of stylish pastiches does not a feature make. The conception is too slight and too fragmented to work as a real feature film. Nice eye candy though, and as Jones says, the sound design also is definitely "lush."

Shown as part of the New Directors/New Films series co-sponsored this year by MoMA and the Film Society of Lincoln Center and sown in New York at both the Walter Reade Theater and MoMA's Titus Theater in April 2010. Amer has been shown at many festivals between September 2009 and spring 2010.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-11-2010 at 03:36 PM.

-

Sander Burger: Hunting & Co. (2010)--ND/NF

Sander Burger: Hunting & Co. (2010)

Modern marital meltdown

In this Dutch film, the director's second feature, Burger and his collaborators on the screenplay, Dragon Bakema and Maria Kraakmank (who also play the two main characters, Tako and Sandra) have devised a chilling and powerfully disturbing study of the meltdown of a marriage. Tako's father has died, prompting him to move from the big city back to the small town of Den Oever and take over his father's bike shop. His mother moves to a retirement community, and Tako and Sandra move into the apartment above the shop.

In their synopsis for the press kit, the filmmakers write, "Tako and Sandra really shouldn't have married in the first place. The only things they have in common are superficialities and material happiness. The interior of their house, made up of furniture and trinkets from IKEA and Habitat catalogues, is a reflection of their passionless relationship. They both work hard -- Sandra at an employment agency and Tako at the bike shop -- yet there is hardly any communication between them."

This partial description shows both the strength and the weakness of Hunting & Sons/Hunting & Zn. The film makers treat their young couple, whose marriage we witness, like insect specimens on a tray. It's good that the trajectory is quite clear, and that doesn't make watching what happens any less surprising and disturbing. Though the outcome, in the manner of classical tragedy, is inevitable, its specifics are not the less surprising and disturbing.

Perhaps here the doom is sociological and psychological. It is also a mystery. Or, to go on with the insect metaphor, it is like the image in King Lear: "As flies to wanton boys are we to th' gods, /They kill us for their sport." For us, Tako and Sandra are brittle creatures. The go back and forth from work to house, blithely greeting each other with comically jaunty "Hi's" and "Hey's. And they indeed have little else to say with each other.

The are people, though, and when, as the synopsis goes on, "problems worsen as Sandra gets pregnant," we are not looking down from above but watching Tako disintegrate as he tries all the wrong things to remedy the main problem -- that his wife turns out to have an eating disorder and keeps passing out. What may have worked for her as a life stile before without attracting attention, no longer does with another being growing inside her. After her first passing out in the bathroom, which causes Tako to panic and call an ambulance, tests show that Sandra and the baby are okay. But she is, the doctor tells Tako, dangerously thin -- and as we see in separate scenes, she turns out to be much more into working out at the rowing machine of her gym than taking nourishment, even now.

Burger is skillful at throwing down hints at first and later at letting the devolution of the relationship slowly unfold. In an early scene, Sandra freaks out when a pair of jeans shows the crease of her undies in back: too tight! That has significance later, of course. When she first throws up, it's from the pregnancy. There's something disquieting, though, the way she covers her mouth and takes away the covers of the bed she's soiled, as if to hide the signs of her indiscretion. Later, she will throw up again, and not because of her pregnancy.

What happens is ugly, and we can't describe it. Burger is skillful also at showing the separateness of the couple. Rarely has a pair of young people seemed so disquietingly in their own windowless worlds, never more than when Tako takes his drastic measures, and the film cuts back and forth in classic suspense-generating thriller fashion between the two people.

There was something wrong with Sandra, doubtless an insecurity no one noticed before. But now, Tako is the one who completely loses his hold on everyday reality. There is excellent control of process here and throughout the film, which moves from joy to panic: at first, so much "happiness," and so much emptiness. And so many images that become haunting later -- such as Sandra, caught turning toward Tako when he opens the bathroom door, wrapped in a towel, her face masked in white cream, peering out at him surprised like an owl -- or a ghoul.

Another element is the bike shop worker, Patrick (Noël Keulen), and the couple's two mothers, whose reactions ironically contrast with their children's. Sandra's mother is warm and joyful; Tako's unresponsive. Ironically too, Tako's mother is stingy with food, while he is a chunky fellow who likes his pasta and beer.

The elements are simple here, but it's a sign of the filmmaker's fine control of the material that the marriage meltdown becomes a horror show from which you can't look away, much as you might like to. This is strong and memorable stuff. But the weakness for us as modern observers is that we don't accept the strict determinism of the writers' conception. How do we know that IKEA furniture means a couple is superficial? Do their happy greetings and small conversation really mean they have no love, no depth in their relationship? How do we know their marriage was doomed from the start? And if it was, isn't this drama, for all its messy thriller feel, just a little too tidy?

Hunting & Zn was introduced in the Rotterdam Film Festival early this year. Shown as part of the New Directors/New Films series at the Walter Reade Theater and MoMa, in New York City, April 2010.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-06-2014 at 01:11 PM.

-

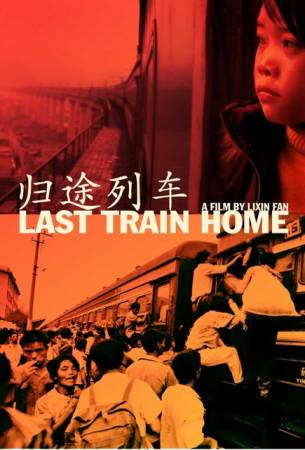

Lixin Fan: Last Train Home (2009)--ND/NF

Lixin Fan: Last Train Home (2009)

"Push! Don't Push!" (voices from the crowd mounting a train)

Last Train Home is a particularly sad and wearying example among a number of documentaries about human upheaval and the destruction of traditions and family values in today's China. A hundred and twenty million Chinese workers in far-flung places hurry back home every Chinese New Year, a vast temporary "migration," and the only time in the year divided families are reunited. Using the microcosm approach, the Canadian-Chinese filmmaker Lixan Fan chronicles the vicissitudes of this massive journey and the impact of separations for the rest of the year by latching onto one small family, the Zhangs, who come from a farm in a remote area to work in Guangzhou, a major industrial city in the south. The parents of two children, Chen Suqin and her husband Zhang Changhua, left sixteen years ago to earn money to support the kids.

The family was dirt poor, the grandmother tells us. She and her late husband were left with the task of raising Chen's and Changhua's daughter Qin and younger son Yang. Yang is in school, fifth in the class, which his parents don't like. He should be number one. "I don't want to work too hard," he says. What does he care? His parents only come to tell him this once a year, at the time of that vast New Years "migration." Yang, Qin, and their parents aren't often in touch. They don't have cell phones.

In the case of teenage daughter Qin, the resentment is huge. She outspokenly declares that her parents abandoned her for most of her young life and she can't forgive them for this. She feels the country is a "sad place." This leads to the deepest irony of the film because she quits school to go away and work first in a garment factory, later in a cocktail bar in a boom town. This despite the fact that the purpose of her parents going away to work was so she and her brother could rise above peasant or laborer status through better education. It doesn't look like Qin is going to do that.

Yang is in middle school. Those words of his justifying fifth place in class, however, show that he, like Qin, is probably abandoning the traditional values of hard work and sacrifice -- values that fueled China's economic boom, but now are being undermined by it. Because of the boom, evident everywhere, even the poorest of the poor are seduced by glitzy fantasies of easy wealth and giddy fun. And the enormous displacements caused by the boom in themselves make the Chinese family structure grow weaker.

The film seamlessly follows Qin and her parents and documents several of the New Years migrations. The trip begins with days of struggle to get tickets and the last trip teeters on the verge of becoming a full-fledged humanitarian disaster. Masses of people wait in the station for five days, herded by terrified cops. This is when Chunghua has gone to see Qin and persuade her to come back with them. He and Suqin are hoping Qin will go back to school. Instead, perhaps because of the enormous stresses of the journey, the film descends into Jerry Springer territory upon arrival and in front of Grandma and the camera father and daugher have a huge verbal and physical fight. Qin addresses her father in foul and abusive language and he beats her, and she strikes back. Later Qin goes elsewhere and the film shows her briefly working in a huge noisy cocktail bar, which is crudely contrasted by rapid crosscutting with the parents' numbing sweatshop work and the quietude and beauty of the farmland from whence they all came. The cocktail waitress phase recalls another Canadian documentary about China, Chang Yung's award-winning Up the Yangtze, a film on which Lixin Fan, a Canadian who immigrated from China, worked as associate producer, translator and sound recordist. Up the Yangtze focuses on human upheavals caused by the Three Gorges Dam, as does Jia Zhang-ke's fictional Still Life. Another semi-documentary about social change in China that has earned much praise is Jia's 24 City.

Nothing can equal the magic of Still Life or Jia Zhang-ke's other films about modern China. The family interchanges in Up the Yangtze were similar to Last Train's, but were more subtle and hopeful. The impression that remains from Lixin Fan's film is the sullen defiance of the children and the weariness in the parents' faces, and the skillful documentation of the horrific crowds cramming into holiday trains. A documentarian sticks with his or her subjects, and Fan does this faithfully, but one may perhaps be forgiven for wishing a more interesting, articulate family had been chosen. Because there is no narration, you would have to read the press kit that goes with the film to know that the Zhangs were prevented by law from taking their children with them; that migrant workers like the Zhangs are cruelly discriminated against; and that a large number of them, perhaps a third, are girls 17-25 years old, like Qin.

This film is vivid and some of the images are fine. This is a strong first film by the young Lixin Fan. Chunghua and Chen provided remarkably intimate (perhaps too intimate) access, but the "human interest" fly-on-the-wall focus can limit a documentary's scope and narrow the amount of information it conveys. A picture is worth a thousand words, but a couple thousand words can be worth a thousand pictures. A few brief interviews with young men on the migrants' New Years train are glimpses of a broader view. One man says he works at a place stringing tennis rackets for all the major foreign brands, but that China has no tennis racket brand of its own. We are just a country of suppliers, he says, and we get paid the minimum price. Despite its boom economy China is still full of very poor, exploited people, and the whole country is like one giant exploited migrant worker. In his own statement of purpose for the film, Fan wrote, "China’s booming economy is largely based on exploiting the vast population of cheap labor. Sacrificing the poor for GDP growth, the country runs the risk of making millions of families separated and their children (wind up) uneducated. These issues could all pose serious backlash against the country’s ambitious goal."

Last Train Home won the Best Feature-Length Documentary award at the 22nd International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam and was nominated for a similar award at Sundance. It was shown at the March-April New Directors/New Films series at Lincoln Center and MoMA in New York.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-12-2016 at 02:52 PM.

-

Mads Brügger: Red Chapel (2009)--ND/NF

MRS. PAK, JACOB, AND MADS BRÜGGER IN RED CHAPEL

Mads Brügger: Red Chapel (2009)

Ceremonial visit

This Danish documentary about a small performing group's visit to North Korea is described in a festival blurb as venturing "into territory somewhere between Michael Moore and Borat" but the key point is "bankrolled by Lars von Trier’s Zentropa production company." Here, we are in the realm of von Trier and Jørgen Leth's Five Obstructions, a filmed set of challenges dreamed up by von Trier, except that this time the challenge is to fool a set of North Korean minders and make a film that will show up the dictatorship, right in front of their eyes -- a pretty dangerous Obstruction. The group's visit, filmed all along the way by Mads Brügger's team and with him in charge, is technically a mission of cultural exchange. The North Koreans think it's a chance for manipulation and propaganda about how wonderful the country and its capital Pyonyang and their Dear Leader Kim Jong-il are. For the Danes, it's a chance to show up their hosts for the pawns and robots and fascists they are.

Mads Brügger's secret weapon is half his two-man Red Chapel comedy troupe, made up of young men born in Korea who've lived all their lives in Denmark and think of themselves as Danish, but a little bit Korean. Jacob Nossell is spastic -- the word he uses for himself. He has cerebral palsy, walks clumsily, and when he speaks, it sounds like it's coming out of a wind tunnel full of laughing gas.

The thing about Jacob is that he makes the North Koreans profoundly uncomfortable. There are no handicapped people on view in the whole country, least of all in Pyonyang, the eerily empty showcase capital where the visitors spend most of their time. Anything "not perfect" is not allowed to be photographed by the visitors, even a military unit practicing a march; that's an indication of how physical non-perfect-ness is viewed. It's not to be viewed. So the North Koreans don't know how to deal with it. Rumor is that in North Korea handicapped people are put away or snuffed out or held out of sight in reeducation camps around the country that are full of people who have committed even tiny crimes against the state, like sitting on a portrait of Kim Jong-il.

But Jacob, though handicapped, is cute and endearing; he smiles a lot and looks kind of hip; he has spiky hair. He's also very outspoken. You can also feel how Danish Jacob and Simon are, though that is one of many things the North Koreans don't want to see. In their eagerness to fool others, they themselves are easily fooled. The visitors' chief minder, who is with them every step of the way and acts as their translator, Mrs. Pak, falls totally in love with Jacob, in a motherly way, perhaps initially out of pity. She hugs him and practically drools over him and tells him she wishes he were her son. The twist, one of several, is that Jacob is initially repelled but ultimately touched by this.

Jacob's spastic way of talking is so distorted, nobody in North Korea can understand him when he speaks Danish, so he has a secret language the group and we can understand and the North Koreans cannot. When he looks away from Mrs. Pak and says "I feel like I'm being smothered -- I can't breathe!" she has no idea what he's saying.

Jacob's partner is the chubby Simon Jul Jørgensen. Simon aims to perform an acoustic rendition of Oasis’s “Wonderwall” accompanied by a choir of Korean schoolgirls, and Jacob, who uses a wheelchair for longer walks, is to accompany him. Simon is ostensibly the leader of the Red Chapel comedy group, but it is Jacob who matters here. He is the secret weapon and also the linchpin of this engaging film, which at first you think isn't going to work, but eventually is awesomely revealing.

The tour, which is narrated by someone who sounds quite like Lars von Trier (it's actually Poul Grønhøj, I think), runs into several key "Obstructions." First of all there is Jong Se-jin, a theater person who is assigned to Red Chapel along with Mrs. Pak, and when he watches Simon and Jacob doing their routine, which is strictly designed to be silly, crude, and funny, neither he nor any of his assistants is pleased. They clap, but their facial expressions show stony distaste. The absurdly stilted downright laughable toy kingdom style of the country is revealed early on when the visitors are taken to bow down before a large statue of Kim Il-sung, father of Kim Jong-il. When Mrs. Pak is asked what she feels about the Dear Leader's dead father, she breaks into tears. The narrator interprets this as being the only way she can express how awful it is to live in a country dominated by these two autocrats, one dead and the other crazy.

After the troupe is set up in a theater and do their performance in rehearsal, the Korean theater person steps in with some "suggestions." Actually what he wants is to remove any shred of Danishness from the performance and substitute an entirely new routine, with different costumes and props. A key aspect: Jacob is to remain in his wheelchair for the entire performance and then appear to walk up out of it normally at the end, acting as if he isn't handicapped, just pretending to be. Something has to be devised to hide that an actual handicapped person has been allowed to perform on a North Korean stage. A lot more manipulations are introduced, and Simon and Jacob are given Kim Jong-il suits to wear, and King Il-sung buttons to pin on, showing they're safe. The performances by young students from a special theatrical school speak for themselves. The little girls and boys are sad and scary. But even Jacob begins to see that in some ways, dictatorship works, and some people are happy with its order and simplicity. There's something sweet and sad about Mrs. Pak.

Then comes a photo op you wouldn't believe: a chance to be part of the country's biggest event of the year, a commemoration of the day the Korean War began, started, according to their mythology, by the Americans. There are many explanations of how evil the Americans are. The Danes aren't expected to mind. Mrs. Pak, Mads, and Jacob in his wheelchair participate in the march with everyone raising their right fist in a fascist salute in honor of the Dear Leader. Jacob breaks down at this. He will not raise his right fist. He's had enough of this whole charade. Luckily, nobody but us and the Danes know what he's saying. Before the end of the film, though, Jacob is playing and having a good time with kids. In the end the film, which is a tad less subversive than it may want to be, is as much about Jacob as it is about North Korean's fake exterior and hidden evils, and seeing the world from his point of view is an eye-opener in itself. Meanwhile we've gotten a view of a country rarely penetrated by westerners.

Red Chapel/Det røde kapel, 82 mins., debuted at Toronto Hot Docs May 4, 2009, showing at 19 other fests listen on IMDb between that date and May 2019. It received Sundance's World Cinema Grand Prize Jan. 22, 2010. Screened for this review as part of New Directors/New Films in March-April 2010 at the Walter Reade Theater, Lincoln Center and MoMA, NYC. US theatrical release was Dec. 29, 2010. Metascore: 58%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 06-30-2021 at 10:40 AM.

-

Hong Sang-Soo: Like You Know It All (2009)--FCS

KIM TAE-WOO (LEFT) STARS IN LIKE YOU KNOW IT ALL

Hong Sang-Soo: Like You Know It All (2009)

Bumbling hero

Hong Sang-soo has been one of the darlings of the exclusive New York Film Festival; this time his new one is included in Lincoln Center's also important but less visible Film Comment Selects. As has happened before, Hong focuses here on a Korean film-making auteur, an ironic version of himself, and the subject matter is man-woman relationships, with infidelity a key issue, and macho self-importance an ever-present given. Though the title may be an over-simplification of the Korean original, the implication is there, of a man who's too full of himself -- but is having that pointed out to him repeatedly either by implication or directly in the dialogue. There are two main, and parallel, sequences in this 126-minute but surprisingly light and watchable film, one of the director's visit to a local summer film festival in the town of Jecheon where he's meant to be a juror, the other a lecture to a group of film students where he becomes momentarily involved with the young wife of a local art celebrity. I liked this one better than Hong's last, the 2008 Musée d'Orsay-commissioned and Paris-set Night and Day. Hong works best in Korean settings, and this new film further pushes its narcissistic Hong hero out into the world. Being in Korea, the protagonist has lots of people he can talk to, and, importantly, get very drunk with; and with no homesickness to contend with, the laughs flow as never before in a Hong film.

The director is Koo Gyung-nam (Kim Tae-woo), and in the film festival section he's delicately but cruelly mocked -- though that's balanced somewhat throughout by his appealingly self-questioning voice-over. Seen falling asleep at screenings and later involved in a very embarrassing meeting, he eventually has to withdraw before his jurying job is done, and he gets a surprising blast of abuse from the woman organizer that satirizes the egomania and personality clashes of the festival scene. Earlier Koo encounters a now popular and well-paid director (Kim Yeon-soo) who was his admirer when they were younger, practically his groupie. He can claim artistic superiority, but he still can't help envying the money and the popularity. Koo also encounters a young porn star (with her mother!) who's recently been cast in an art house film and now promotes herself as a legitimate actress. This shows off Koo's hypocrisy, as he makes absurd promises to people he'll never see again. It's when he meets an old friend and is invited to dinner at the man's house and meets his young wife that things eventually get very uncomfortable for Koo and he is forced to leave town.

Part two begins twelve days later when Koo goes to Jeju Island to talk to a film class. Still more drinking happens, with proclamations on the meaning of life, arm wrestling (which Koo at first wins -- he's one of Hong's fittest and trimmest protagonists), and a meeting with a yet older friend, a famous painter, again with a young wife, Gosun (Ko Hyun-jung). Sure enough, Koo is going to have a connection with her, and as in part one, a handwritten letter from a married woman initiates a disastrous encounter. The parallelisms of the two parts and the artificiality of some of the dialogue, especially when it's pointing to the egotism and poses of the art film and festival world, strangely do not keep Hong's film from having a natural, easy flow, and the predicaments Koo gets into are always surprising enough to keep you interested. Think Rohmer, the foreign director most often mentioned in connection with Hong: both combine sometimes obviously written dialogue with improvisation -- on the part of actors and director, who in Hong's case tends to make up scenes from day to day during shooting. This blend makes both filmmakers' artificial cinematic worlds somehow seem absolutely natural and right. In both cases you plunge into that world with delight, even though sometimes what you've seen in their various films tends to blend together a bit, while certain scenes remain in the mind, classic and unforgettable.

The sequences between Ko Hyun-jung as Gosun and Kim Tae-woo as director Koo are the most memorable, intimate, and serious in the tale; Gosun is a fascinating woman who's articulate, sure of herself, and attractive enough to be more than a match for director Koo. Variety's Justin Chang has suggested that while Like You Know It All can be seen as a smaller diptych, this film and Hong's Woman on the Beach can be read together as a larger one, a point underlined by the presence of both these actors in both films. Some who've commented on Like you Know It All online seem to have suddenly fallen out of love with Hong Sang-soo. But the arrival of a film as accomplished, rich, and entertaining as this one is hardly the right moment to desert him.

Like You Know It All/Jal aljido mothamyeonseo was presented at Cannes, Toronto, Vancouver, London, and other film festivals, mostly in 2009. Shown as part of the Film Comment Selects series at the Walter Reade Theater of Lincoln Center, March 2010.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-06-2014 at 01:15 PM.

-

Mariano Cohn and Gastón Duprat: The Man Next Door (2010)--ND/NF

DANIEL AROIZ AND RAFAEL SPRENGELBURD IN THE MAN NEXT DOOR

Mariano Cohn and Gastón Duprat: The Man Next Door (2010)

An empire crumbles

This fourth collaboration between Argentinians Mariano Cohn and Gastón Duprat is a drolly ironic study of bourgeois insecurity in which the viewer's sympathies gradually shift from the apparent protagonist to his apparent enemy -- a crude neighbor who shatters his calm by knocking out a hole in a wall facing and adjoining his especially perfect house.

All focus is on Leonardo (Rafael Spregelburd), a successful designer who lives with his wife and teenage daughter in the university town of La Plata, Buenos Aires in what is essentially a museum: a Le Corbusier house, the only one in Latin America. It's a real house: it's called the Curutchet House. It is ample and meandering; we never get a look at all of it at once. One of its windows faces a white wall. That wall belongs to a house. Behind that wall, in an apartment, is a macho, gravel-voiced used car salesman called Victor (Daniel Aráoz). This man is remodeling, and he wants a bit of light. The film begins with a big sledge hammer knocking a hole in the wall.

At first one's sympathies are with Leonardo, especially if one has ever had to deal with nosy, intrusive, or annoying neighbors, as many of us have. Victor could be doing anything, chopping down a tree, building or destroying a fence, even harboring a noisy dog.

The sly part comes when the personalities of Leonardo and Victor are combined; because, try as he might to keep it cold and businesslike, Leonardo can't stop Victor from being friendly and insisting they discuss the issue "as friends" in a café. Sure, Victor is a bit crude, and this is, typically for an Argentinian film, largely about class. But the class Leonardo increasingly shows, as the picture builds up, is world class priggishness and Olympic grade cowardice. His self-importance is endless, but nothing he does ever justifies it. Sure, he is a successful designer, but the house only underlines the fact that he's no Le Corbusier. Moreover, he keeps telling Victor he's terribly busy when he's so rattled by the noise (as Victor has the window changed back and forth) that he isn't doing anything. His wife is always on his case, and his daughter is always dancing in her room wearing headphones. Leonardo is even cowardly in the face of his daughter's insolence and hostility. The Le Corbusier house may be marvelous. People are constantly coming around to photograph it and annoying Leonardo by even sometimes asking to be let in (out of the question; but their repeated appearances add to the growing sense of menace, of the crumbling of Leonardo's world). Leonardo resents that the house is listed on Wikipedia (it is; look it up). Victor acts friendly, and so Leonardo pretends to act friendly too, meanwhile making fun of Victor and exclaiming at his presumption and gaucherie to sycophantic friends.

Leonardo began by telling Victor what he's doing was illegal. In fact when he finally consults with a knowledgeable friend it turns out Victor has the right to put in a window. It just needs to be higher up and narrower. But if the law forbids a big squarish wall, when it comes down to actual cases that may be hard to enforce. Too weak to confront Victor on his own or in a café (though he does consent to enter his kitschy van), Leonardo resorts to pretending it's his wife who won't allow the window, and then his father-in-law, who in his lies are far more authoritative and unyielding than he is. It becomes increasingly clear that Leonardo is ineffectual. The hole in the wall was from the start the symbol of his impotence.

Leonardo is an asshole; and so are his wife and daughter. He's also hollow, like the family inhabiting the modern house of Jacques Tati's Mon Oncle. With all due respect to Le Corbusier, such houses are not cozy, and in both cases people are making things more important than people. Victor (ironically, since he quite lacks Hulot's fey delicacy) is like Monsieur Hulot. He's a human being, and the threat he poses to Leonardo is that he connects on a human level. Leonardo is just a self-important snob. His sense of superiority is focused in his notion that his house is of transcendent importance; that the world belongs to him.

As Victor, Daniel Aráoz's performance is a marvel of control that hovers perpetually and tantalizingly between bonhomie and menace. And the modulation of the film is equally subtle in the way it gradually shifts the viewer's sympathies from Leonardo to his annoying neighbor; the way little by little, Leonardo and his family become the truly and deeply annoying ones.

The Man Next Door/El hombre de al lado is a very simple story: the premise takes such good care of itself that almost any little incident that happens from day to day enriches the situation and adds layers to its implications. This is the story of a process, a gradual meltdown. Victor turns out, in a surprise twist, that, unfortunately, takes the film into another, unrelated genre, to be in fact a very good neighbor indeed. What's good about The Man Next Door is the way it's simultaneously both symbolic (and satirical) and very practical and down-to-earth.

The film has a special cool, flat, grayish look that is elegant and distinctive, and it won the cinematography prize at Sundance. It was in several festivals; is scheduled for release in Argentina in September 2010; and was chosen to be part of the New Directors/New Films series of the Film Society of Lincoln Center and shown at the Walter Reade Theater and at MoMA, March 31, 2010 (MoMA) and April 1 (Walter Reade).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-13-2010 at 02:01 PM.

-

Alexei Popogrebsky: How I Ended This Summer (2010)--ND/NF

How I Ended This Summer trailer.

Alexei Popogrebsky: How I Ended This Summer (2010)

Trout fishing gone wrong

"How I Ended This Summer:" it's not a serious title but a mocking one, in bad Russian grammar, like something scrawled at the top of a boy's back-to-school essay. And it's Sergei (Sergei Puskepalis) mocking young Pavel or Pasha (Grigoriy Dobrygin), a temporary trainee at his remote Arctic meteorological station for the summer and so, to Sergei, like nothing more than a kid on a lark. They are alone together on the island of Chukotka, Russia's northernmost territory, and before the film ends, its title will have assumed a grave irony. The dour Sergei is every just-out-of-college boy's summer employment nightmare -- dour, disapproving and harsh with the young man. Pasha is the better one at the modern digital data-recording devices, but he hasn't spent a lifetime at this harsh, lonely work and so, for Sergei, whose wife and daughter now are back on the mainland, Pasha doesn't really count. Sergei's thing is sneaking off for a bit of trout fishing in a lagoon. The trout remind Sergei of his wife, who has loved their taste, fresh salted, when staying on the island herself, perhaps in more cheerful times.

Pasha spends his free moments leaping between old rusty 100-gallon cans (not an approved activity), listening to loud rock or techno on his headphones, or playing a shoot-em-up video game. There's an isotope signal whose Roentgen level he's tested (it's high) and the men must go out on foot to take readings and send data from their equipment via radio every few hours. The good-looking young Pasha's lighthearted mood sinks every time he's in the presence of the tight-lipped, disapproving Sergei. Dobrygin and Puskepalis have an endgame coming. Both are excellent in this tense, nail-biter of an imploding actioner. For anyone whose thing is edgy, minimalist drama in challenging natural locations, How I Ended This Summer comes very close to being a wonderful film. Unfortunately it unreels on Russian time, which means it goes on twenty minutes too long, and the final action strains credulity.

Actors and setting are nicely balanced here. Apart from his two principals, talented young Russian director Aleksei Popogrebsky draws much of his film's essential strength from making the bleak locations vivid and ever-present -- the more so because the only music heard is what Pasha listens to on his headphones. Despite the summer setting, the surrounding landscape is chilly and dim, with never the marker of real nighttime darkness. The shoddy interiors are anything but cozy. Pavel Kostomarov's Red camera cinematography makes a virtue of digital coldness, alternating closeups of faces and objects with distant shots that bring out both the loneliness and the austere beauty of rock, sky, and sea. As Sergei warns and gunshot holes in a ceiling reveal, the weather station is a place so stark and difficult strong men have been known to go mad and brutally settle scores on the spot. Sergei admonishes Pasha never to go out without a shotgun and to keep it loaded, because there are bears -- white ones, big and light on their feet.

First the film establishes Pasha's playfulness and Sergei's hostility. Ironically, the two will bond toward the end, when everything has gone terribly wrong. They make constant two-way radio reports of readouts. Their control base is the deus ex machina of the piece.

While Sergei is off fishing the first time, Pasha gets a crucial message that, due to the poor communications between the two men, he lacks to courage to pass on to his boss on his return -- a mistake that is magnified as time goes on and pressure keeps coming from headquarters to say what he's done. Every activity the two men share now is heavy with portent, the danger of telling, the equal risk of keeping silent, the growing tension of our awareness of this dilemma and Pasha's growing inner conflicts. Still oblivious of the news though Pasha is inwardly frantic with worry and increasingly conflicted about what to do, Sergei goes out on a second fishing trip, and Pasha gets lost looking for him, near the lagoon, pursued by a bear in the fog.

That's not the end, and up to there, the suspense has been tremendous. From then on, Pasha's motivations and his transformations become harder to follow and the action gets too erratic and drawn-out. Or so it seemed to me. Perhaps if you buy sufficiently into the crazy-making potential of the environment and the volatility of the relationship between the two men, you'll ride with the whole adventure. Some do, certainly: the film won prizes at the Berlin film festival (best acting shared by the duo and Outstanding Artistic Achievement for d.p. Kostomarov), and a big distribution deal. For sure, Popogrebsky knows how to create the sweet torture of true action suspense, the kind that requires nothing more than two men at the end of their tether on a mean gray strip of the far north.

Shown in New York as part of the New Directors/New Films series at Lincoln Center and MoMA in April 2010. Russian theatrical release is set for April 1, 2010. (Russian title: Как я провёл этим летом /Kak ya provyol etim letom.)

Grigoriy Dobrygin, Sergei Puskepalis

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-12-2016 at 02:48 PM.

-

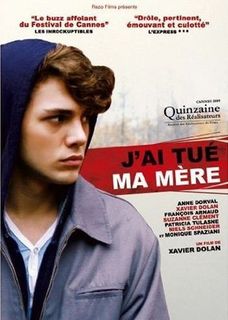

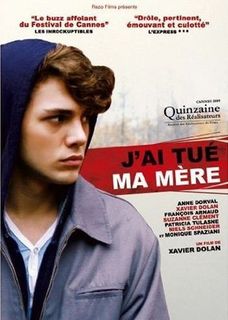

Xavier Dolan: How I Killed My Mother (2009)--ND/NF

ANNE DORVAL AND XIAVIER DOLAN IN "J'AI TUÉ MA MÈRE"

Xavier Dolan: How I Killed My Mother (2009)

'Maman': can't live with her, can't live without her

In this debut feature film in Canadian French, Hubert (Xavier Dolan, who wrote, directed, produced and stars) is a gay Montreal teenager who, as the title J'ai tué ma mère hyperbolically informs us, is not the least bit fond of his female parent. The male one lives in another part of town and is seen only briefly, and later. Hubert doesn't actually resort to violence against Chantale (Anne Dorval), as might have happened in an early Ozon film; he's just verbally cruel to her; unfortunately for the emotional dimension of the piece, she's never very deeply stung by his many barbs, though she can return critical salvos aplenty when called upon. And so the mutual abuse goes on and on and on, chiefly at the dinner table, where she often serves him his favorite foods, or in the car, where she chauffeurs him to and from school.

There is a car scene in Cédric Klapisch's L'Auberge espagnole, where Romain Duris explodes with a nasty epithet, cutting off a tiresome speech by his overly understanding old hippie mom (Martine Demaret). Just one explosion. That's all it takes to show all a son's pent-up annoyance at his well-meaning but burdensome mother. What makes it so effective is that it's so unexpected. Duris' character, who happens to be called Xavier, is always the good and polite and dutiful young man. Dolan is not so efficient by a long sight. Hubert and his mother have an ongoing verbal battle that never goes anywhere, and the louder they yell at each other, the less it matters to us. What we can say is that Dolan gives his mother a voice. She looms very large in the story. Hubert really, really wants to get away from her even though he kind of loves her. The difference between him and Klapisch's Xavier is that Xavier is ready to go out on his own, and Hubert isn't: he needs his mom terribly -- there's the rub. He has to have her around to define himself by vociferously enunciating the way he despises everything about her. The truth is she's not at all a bad mom; she's just a sounding board for Hubert's teen angst.

Chantale isn't developed in great depth, but even less developed is Hubert's boyfriend, a schoolmate called Antonin (François Arnaud) -- an adolescent homage to Antonin Artaud (there's one to Arthur Rimbaud too). Yes, the two boys kiss a bit, and get naked together after an embarrassingly filmed scene in which they splash-paint Antonin's mom's office space à la Jackson Pollack and, of course, get paint all over each other. Antonin's liberal mom Hèlene (Patricia Tulasne), cool with the boys' gayness, provides a contrast to Chantale, and is also inadvertently the way Chantale finds out her son likes boys.

Hubert's insolence eventually leads to a meeting between his mom and dad (Pierre Chagnon) and a decision to send the boy off to a boarding school. At this point things get rather confusing. Very quickly Hubert is at the school, with a new, naughty dope-smoking boyfriend -- but then he's back home again pouring out his love to Chantale while on speed, and then he's apparently run away from the school. The headmaster calls Chantale to tell her, and implies, to her intense annoyance, that it's all her fault. The sequence is too fast all of a sudden. There is also a relationship with one of Hubert's earlier teachers, Julie (Suzanne Clement), that is a bit over-the-top, and badly defined considering Hubert's consciously gay. And that fact, given all the yelling between mother and son and the latter's outspokenness, is something you'd think would have come out earlier; presumably he finds her too clueless to tell. The chronological uncertainties and unclear motivations are various. And yet, due to the universality of filial conflicts and the vivacity of the proceedings, I Killed My Mother has crowd-pleasing potential.

It would be a bit churlish to damn this first feature for its unoriginal storyline and annoying mother-son shout-fests and other faults. There's a modicum of life in every scene of I Killed My Mother, and, considering the source, it's precocious and brave. Xavier Dolan was nineteen or so when he made it and seventeen when he wrote the screenplay. Let's cut the kid some slack. If he keeps at it, this could be like the autobiographical first novel so many writers throw away; and in future as his maturity grows, Dolan may repudiate this youthful effort. It just happens that the Montreal film industry and Dolon's supporters, maybe because he's gay and poutily cute, because he's been in pictures and ads since he was a kid and he's got connections, or because he's got chutzpah, it got made into a movie, with Red One images digitally transferred to 35mm. With alternating bright color scheme for the boyfriend's liberal household and a dull one for home; self-indulgent black-and-white monologues supposedly shot in the bathroom with a cheap video camera that look much too handsome for that, and some color exteriors that are also handsome, if derivative, the film has a look, or looks, that go beyond the ordinary, even if they don't quite jell. There are borrowings from Truffaut, Wong Kar-wai, and lots of others that herald a giddy love of movies. Dolan is good at playing himself (not everybody is), and the camera likes him. If he continues to make movies -- and with the encouragement he's gotten, which includes several awards at Cannes, he's unlikely not to -- Xavier Dolan may turn into a good filmmaker.

J'ai tué ma mère was chosen to be shown as the closing night film of the New Directors/New Films series of the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and screened in early April at the Walter Reade Theater and MoMA. The film opened in France July 15, 2009 and has been shown in over 20 festivals.

FRENCH DVD COVER

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-12-2016 at 02:40 PM.

-

Mia Hansen-Løve: The Father of My Children (2009)--ND/NF

CHIARA CASELLI, MANIELLE DRISS, ALICE GAUTIER, LOUIS-DO DE LENCQUESAING

Mia Hansen-Løve: The Father of My Children (2009)

A film about cinema and family

The life and death of legendary French independent film producer Humbert Balsam, who got many an edgy project made against all odds, is the inspiration for Mia Hansen-Løve's second feature, an elegant, sensitive portrait of a passionate man of the cinema and those around him in the period up to and after his suicide. The Father of My Children confirms the impression already given by the director's 2006 All Is Forgiven that she is a fine new talent with a special gift for delineating families and showing how children grow up under pressure with and without difficult fathers.

From the moment Grégoire Canvel (a very fine Louis-Do de Lencquesaing) walks onto the screen in the first frame smoking and talking on his cell phone, he dominates the film until he vanishes. Grégoire is always well-dressed, genial, and charming. (Hansen-Løve has described Balsan, who encouraged her to make her first film, as a man of "exceptional warmth, elegance and aura.") He adores his young daughters Valentine (Alice Gautier) and Billie (Manelle Driss) and more grownup one, Clémence (Alice de Lencquesaing of Summer Hours), and his loyal, loving, but sometimes complaining Italian wife Sylvia (Chiara Caselli); he's unfailingly affectionate with all of them. But he may not remember the earrings from Venice that he gave Clémence, and he may spoil a trip to Italy for Sylvia by disappearing for long business calls.

The first sequence, a drive in a Volvo station wagon to his big country house outside Paris to spend the evening with his family, is an indication how things are gong. The police stop Grégoire for speeding and not fastening his seat belt, his car is impounded, and he's taken to the local station because he's "run out of points." Grégoire is running out of points everywhere. His catalogue has been used for collateral for loans. He has an enormous debt at the film lab. Friendly meetings with his lawyer and his banker don't help. An eccentric Swedish director is costing him a fortune for a shoot outside Malmö. A team of Korean filmmakers is arriving to be hosted and turns out to be double the expected number. At his office his own Moon Films team, his second, surrogate, family, faces a host of problems, most of them financial. Nevertheless when he gets home that night and Valentine and Billie, charming and happy, put on a little show, he delights in it. He excels at hiding the pressures he's under.

Grégoire seems unstoppable. He must take the bus but makes a virtue of that, meeting a new filmmaker and reading the script of another while riding into town (he wants to use both). While warnings are being sounded everywhere, he keeps surging forward. The charm still flows and so does the enthusiasm for filmmaking and willingness to take on exciting but tricky projects. He champions artists: that's what he cares about, not making money -- though one of his current productions at least seems to be a small success. Still, he knows that the situation is becoming increasingly dire. And the very thing he lives for -- the excitement of pursuing a host of projects at once, which keeps him on the phone even when he's "vacationing" with his family -- is also wearing him down with its relentless tension. Hiding the pressure doubtless heightens its inward effect on him. Moon Films is going to go down. From a wealthy industrialist family, Grégoire considers as a last resort going to relatives to ask for the millions of Euros he now needs to rescue his company from debt. And he knows they would have them, but he can't face the humiliation of taking this step.

With the film's typical delicacy, signs of Grégoire's final meltdown are subtle. He "takes a nap," he stares into space, he goes to "get some air." And then there is the sudden and violent finale.

But that is only the film's midpoint. Paralleling the director's first film, which revisits a wayward dad years later in a second half, this one looks back on Grégoire, struggling to understand his death and discovering his weaknesses, his secrets, and his flaws. But more than that it shifts the focus to the family, the associates, and the company in the wake of Grégoire's sudden demise. Sylvia tries to save the company, going to Sweden to see if another producer can take over that film, talking to the head of the lab to see if it could swallow half the debt. In the end, Moon Films must go under. But Clémence has befriended Arthur (the director's brother, Igor Hansen-Løve) the young would-be filmmaker whose screenplay Grégoire had just taken on; with timid but firm steps, she sets forth in the world -- after finding out something about her father's mistakes and secrets. Sylvia talks of moving to Italy, but the girls all say absolutely no. One of the most touching scenes shows the little girls shaking hands and saying goodbye to Moon Films staff members. The force of the film is again, like Hansen-Love's first, to emphasize forgiveness, and moving forward.

Though Hansen-Løve's All Is Forgiven showed great promise, this is a richer, warmer, more complex film; and she's still in her twenties. With all due respect to Anne Andreu's documentary Humbert Balsan: Rebel Producer (shown at the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema 2007), Hansen-Løve's feature is far more the tribute Humbert Balsan deserves, and its accomplishment is that it gives a sense of the contradictions present in a remarkable man. And Balsan was remarkable: braving the financial pressures the champion of art films endures, he produced nearly 70 films, including Claire Denis's The Intruder, Lars von Trier's Manderlay, and Bela Tarr's The Man from London. De Lencquesaing and Caselli are excellent, but that's only the beginning. Hansen-Løve is great with children and this is an actors' film with many fine small parts, including Eric Elmosnino as Serge, Grégoire's associate; Sandrine Dumas as his office assistant, and Dominique Frot as Bérénice, his on-set production supervisor.

Hansen-Løve's films are both vivid and contemplative, a combination enhanced so far by choosing complex, problematic men as their starting point. An admirable sense of transparency in her work, an equal presence of both emotional depth and detachment, may arise from her skill at showing all points of view. The girls give us ample opportunity to question Grégoire's terrible action. "He didn't care about us," they say; but their mother defends him: "He did care, he adored you, but he was too overwhelmed, and for a minute he forgot." Grégoire was sensitive, charming, eccentric, passionate, but not always to be trusted: he ran away from things. But he still left a beautiful legacy. And The Father of My Children is part of Balsan's; All Is Forgiven is one of a number of projects he inspired that were completed after his suicide, and so Mia Hansen-Løve got her start through him.

After premiering at Cannes in the Un Certain Regard series (Special Jury Prize), Le Père de mes enfants opened in Paris December 16, 2009 to excellent reviews. An IFC release in the US, it is also included in the New Directors/New Films series shown at Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art, New York in March 2010. Included later in the SFIFF April 22-May 6. Opens in New York and Chicago on Friday, May 28 , 2010.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-12-2016 at 02:31 PM.

-

Tanya Hamlton: Night Catches Us (2010)-ND/NF

ANTHONY MACKIE AND KERRY WASHINGTON IN NIGHT CATCHES US

Tanya Hamlton: Night Catches Us (2010)

Revisiting black radicalism and its residue

Philadelphia, 1976. At the death of his father, Marcus (Anthony Mackie) returns to his Philly neighborhood after a mysterious absence. Some years ago he's believed to have pointed out to cops that the husband of Patricia (Kerry Washington) killed a cop, which got the man killed, and the neighborhood writes "SNITCH" in big white letters on the beautiful black Caddy he inherits. The house is to be sold, and Marcus' hostile Muslim brother Bostic (Tarique Trotter) kicks him out, but Marcus stays a while with Patricia and gets to know her inquisitive daughter Iris (Jamara Griffin). From Iris' probing we learn her father was a Black Panther. So perhaps were Patty (as Marcus still calls her) and Marcus.

Iris gets hold of some Black Panther comic books preaching hatred and murder of "pigs" (cops). Marcus tells her these were propaganda created by the Feds. Meanwhile Iris works with Patricia's cousin Jimmy (Amari Cheatom) collecting cans for money. Jimmy turns against the white man who buys the cans off him, feeling he's being cheated; he's hostile toward police, always getting arrested, and drawn to the now dormant Black Panther mystique.

The neighborhood is controlled by DoRight (Jamie Hector) and his gang. Marcus is called upon to frame him. Jimmy gets in bigger trouble. The old flame between Marcus and Patricia is ignited.

These are some of the threads of this interesting first feature by Tanya Hamilton, which was fostered at Sundance. The acting credentials of Mackie (who plays a lead role in Oscar winner The Hurt Locker), Kerry Washington, Jamie Hector, and Amari Cheatom are fantastic, and Jamara Griffin is strong as the precocious pre-teen Iris. Night Catches Us rambles at first, then shifts from contemplative to confrontational as the action heats up. Maybe the various strains never jell. The subject matter is complex: just as Marcus is contemplating his radical past, the film looks back on the Sixties and Seventies from the point of view of African Americans. Jimmy Carter is running for President, and in a speech is heard saying the Panthers are the greatest danger the country faces.

Variety's John Anderson is right: Night Cathes Us' message is staticky and its structure is wobbly. It's not clear how the film wants us to take Jimmy, whether as the new generation of focused anger, or a foolish, out-of-date wannabe revolutionary. Nonetheless the Seventies feel is strong, the images are nice, the acting is fine, and the material is thought-provoking and fresh. Archival footage of the Black Panthers, period soul and music by the group The Roots adds to the atmosphere.

Night Cathes Us premiered in January 2010 at Sundance, and was included in the Lincoln Center/MoMA New Directors/New Filmsseries shown at the Walter Reade Theater and MoMA in late March.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-12-2016 at 02:33 PM.

-

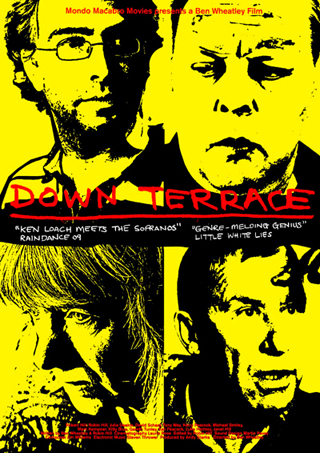

Ben Wheatley: Down Terrace (2009)--ND/NF

Ben Wheatley: Down Terrace (2009)

Five or six ways of killing your friends

Comedic TV actors, writers, and director collaborate on this typically British drier-than-dry, hilarious, and violent feature shot with minimal means. Wheatley used friends as actors, shot most of it in their house, with much improvisation, in only eight days. The film narrates several weeks in the lives of a group of (at first anyway) very ordinary-seeming criminals. Their specific line of work was stripped away in Wheatley's minimalist story line from an original screenplay. It was meant to be "a film about the structure of drug supply in Brighton." In what remains, casual murders alternate with reminiscences about Zen-like doper life in the Sixties, problems of unexpected pregnancy, and cups of tea in the breakfast room.

The characters aren't dapper, but the amoral elan of Patricia Highsmith's Tom Ripley may come to mind as we watch Maggie (Julia Deakin), Bill (Robert Hill), Karl (Robin Hill) , Uncle Eric, Pringle, John and Garvey chat and chop and roll up in plastic associates whose presence has become tiresome to them. Maybe this is The Godfather as Mike Leigh would see it, if his chief writer were Harold Pinter.

Karl and dad Bill seem in the same line of work since both have just gotten out of prison. Amid reminiscing about his days as a seeker of wisdom and the perfect high, Bill, dad of Karl and husband of Maggie, wonders who ratted them out. But Karl is faced with an immediate problem: Valda (Kerry Peacock), who turns up pregnant, she says, with his child. Bill sees fit to question his fatherhood, but Karl thinks it's time to assume a more responsible life. But Karl is staying with his parents and they say he can take in the kid, but never Valda.

The economy of means does not keep the images from being crystal clear and the dialogue has great assurance in the delivery, though it is sometimes hard to follow for viewers from across the Pond. Kitchen sink realism and black comedy make a droll and unexpected combination. The film, which has been shown at a number of festivals, is to be released in the US by Magnolia Pictures. It was included as part of the New Directors/New Films series (end of March 2010) and is the first feature by Ben Wheatley, who has much experience in England in comedy writing for TV and the Internet and advertising. The co-writer and editor was his long-time collaborator and a cast member, Robin Hill. Robin's father is played by his real father, his girlfriend is played by his real girlfriend, and the action takes place at his parents' house in Down Terrace. Thus Ben made what he calls a "pragmatic film," that is, one too practical to put off making, as he long had the "Hollywood" scripts he'd co-authored in the past with Robin, which would have cost too much and taken too long to make and so were always put off.

Down Terrace is likely to have a small but enthusiastic audience. After seeing it at the Fantastic Fest in Austin, Texas, William Goss wrote that after "you find out it was shot in a mere eight days . . . you just want to give up on life." But of course Wheatley and his talented friends brought a great deal of experience to their minimal means. If the success of the film is sufficient to permit Wheatley to move further afield and continue funding his work without mortgaging his house, this may prove as auspicious a debut as Danny Boyle's Shallow Grave; but compared to that film, Wheatley's shows less of a penchant for location shots and on-screen action: this is far more like a theatrical set piece à la Martin McDonagh.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-12-2016 at 02:35 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks