-

Steve mcqueen: Hunger (2008)

STEVE MCQUEEN: HUNGER (2008)

MICHAEL FASSBENDER, LIAM CUNNINGHAM

A powerful and relevant look at recent British history

Steve McQueen, a noted young British artist, has made a powerful first film about the Irish prisoners in H-Block of Maze Prison, Northern Ireland, and the hunger strike and death of Bobby Sands in 1981. The images are searing, both horrible and beautiful (McQueen is aware from Goya that images of war can be both), and much of the film is non-verbal, but the action is broken up by a centerpiece tour-de-force debate between Sands (Michael Fassbender) and Father Dominic Moran (Liam Cunningham) that is as intensely verbal as the rest is wordless, and shot in a couple of long single takes. In Irish playwright Enda Walsh's rapid-fire dialogue quips are exchanged, then passionate declarations, in a duel that's like a killer tennis match: watching, we listen, and the camera, hitherto ceaselessly in motion, becomes still. Hunger, with its rich language, intense images, and devastating story, is surely one of the best English-language of the year, and it understandably won the Camera d'Or at Cannes for the best first film. Like the American Julian Schnabel, Steve McQueen is another visual artist who has turned out to be an astonishingly good filmmaker.

Faithful to the physical details of the H-blocks and the treatment of the prisoners, the film is still honed down to essentials and includes a series of sequences so intense it may take viewers a long time to digest them. As the film opens, an officer of the prison, Raymond Lohan (Stuart Graham), follows his normal routine. His knuckles are bloody and painful; later we learn why. His wife brings him sausage, rasher, and eggs.

Davey Gillen (Brian Milligan) a young Irish republican prisoner, tall, gaunt, and Christ-like, is brought into the prison. He refuses to wear the prison uniform, so, joining the Blanket protest, he's put in with fellow "non-conforming" prisoner Gerry Campbell (Liam McMahon) in a cell whose walls are smeared with feces. Those of us who were around when these events happened (Steve McQueen was 12, and remembers the coverage), remember them so well we could have seen these walls. Campbell shows Gillen hot to receive "comms" (communications) from visitors and pass them to their leader Bobby Sands at Sunday mass.

When prisoners agree to wear civilian garments, they're mocked by the "clown clothes" they're handed out and riot, screaming and yelling and tearing up everything in their cells. They also periodically collect their urine and pour it under their cell doors out into the prison hallway where the guards must walk. The result is a brutal punishment by the prison in which the prisoners are taken out to the hallway and beaten naked by a gauntlet of police in riot gear. An eventual repercussion is that Raymond Lohan is shot dead while visiting his catatonic mother in a home.

A poetic flourish of the meeting between Sands and Father Moran is Sands's story of going to the country as a Belfast boy on the cross country team and going down to a woods and a stream where he is the only one who dares to put a dying foal out of its misery by drowning it. The images this tale evoke become the objective correlative of Bobby's last thoughts when he is dying in the prison hospital.

The central issue was being treated as political prisoners. From 1972, paramilitary prisoners had held some of the rights of prisoners of war. This ended in March 1976 and the republican prisoners were sent to the new Maze Prison and its "H-blocks" near Belfast. Special Category Status for prisoners convicted of terrorist crimes was abolished by the English government. Hunger doesn't focus on ideology or public policy, other than to have the voice of Margaret Thatcher, in several orotund declarations, adamantly denying the validity of the republicans' cause or status. The Sands-Moran debate is more about feelings and tactics.

Another powerful contrast comes when Sand goes on the hunger strike and is taken to the clean, quiet setting of the hospital where he is lovingly cared for and visited by a good friend and his parents, who're even allowed to sleep there during his last days. Though tis segment isn't as strong as the others, Sands' condition is dramatic, heightened by horrible sores, and a report to his parents of the rapid damage to internal organs and heart that his fast will cause. (He was the first of ten IRA inmates to die in this struggle at the Maze Prison. After the hunger strike ended late in the year the British granted the prisoners' demands, but still without officially recognizing their political status.)

It was McQueen's decision to eschew a screenwriter in favor of a playwright for the script, and his choice of his near-contemporary Enda Walsh, an Irishman resident in London, was a wise one. McQueen determined the structure and inspired the paring down. Walsh makes the central verbal scene sing. Its intensity is such that it has no trouble at all competing with the harsh prison scenes. It is brilliant stroke. Great theater you could say, but the film's contribution is to make the whole train of events alive and human at a time when they are acutely relevant to the post 9/11 world of Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib.

Shown at Cannes, Telluride, and Toronto, and reviewed as part of the New York Film Festival 2008. Limited US release came in early December 2009 with excellent reviews.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 01:55 AM.

-

Jia zhang-ke: 24 city (2008)

JIA ZHANG-KE: 24 CITY (2008)

ZHAO TAO IN 24 CITY

Jia Zhang-ke looks at factory life in China

Jia's latest feature doesn't reach out and grab you; rather it builds up a steady accumulation of detail in an artful and partly fictionalized documentary whose central concern is the transition from a planned economy to a market economy in China, with the Cultural Revolution along the way. Jia decided to use actors to play "real" "documentary" talking heads--people who worked at a certain factory now dismantled to become a five-star hotel--or their children, one of them, Su Na (Zhao Tao) working as a "shopper," making good money traveling to other countries and buying expensive goods for rich clients who want to spend but are too lazy to do so. This woman, who wept when she visited her mother in the factory for the first time and saw her numbing job, is the opposite extreme from the aging, now dim-witted "master" of the factory in its early days who worked seven days a week, and used the same tool till it wore down to nothing so as not to waste. The shift in China from the self-effacing collectivist mentality to the current entrepreneurial capitalism is so great that you can imagine why Jia takes refuge in still tableaux of people, composites, and a gallery of talking heads. But this is not as stimulating a film as earlier works like Platform, Unknown Pleasures, The World, or Still Life and will appeal only to the patient.

Actors are used for some of the people because Jia interviewed 130 people and had to create composites. Jia sees no problem in making use of fiction this way in telling fact: life as he sees it is a mixture of historical fact and imagination. He uses poems by classical poets including the Dream of the Red Chamber and William Butler Yeats as well as songs, including "The Internationale" sung by a group of oldsters, pop music, a Japanese classical composer, and contemporary music by a Taiwanese composer. Sometimes the camera is still as a person speaks. Sometimes one person or a group look silently into the camera for a minute or so.

The film, understandably, tells a tale of repression. It also witnesses people who were laid off in the 90's and suffered the lowering of an already frugal lifestyle.

There are strange stories. One woman describes being on a company trip when she and her husband lost their little boy. It was wartime and they felt obligated to go back on the boat to return to work, and they never saw their child again. An attractive woman known as "Little Flower" was the prettiest girl at the factory and when the photo of an unidentified handsome and athletic young man appeared on a bulletin board everyone told her he should become her husband. Silly as this was she began to dream of it--but then they were called together and told he was a pilot whose plane had crashed so he had died due to the malfunction of parts they had made at the factory. They were meant to feel guilty. A woman for years helped her sister in the country by sending clothes and other things to be recycled for her children. More recently she was laid off and became so strapped she had to rely on her "poor" country sister to help her out.

The focus is on the 420 Factory, which was founded in Chengdu, the capital of set up in Chengdu, capital of Sechuan in the late 50s to produce airplane engines. In early days its function was secret and workers, shipped there from all over the country, lived in virtual isolation; kids got into fights if they tangled with the locals, one man recounts. Later 420 was retooled to produce peacetime products such as washing machines.

Known actors such as Joan Chen or Jia regulars such as Zhao Tao and Chen Jianbin work together with unknown crew members to simulate the "interviews." Though Jia's logic in using this method to present composites makes sence, the effect is to undercut the sense of realism. Probably the best thing about the film is the beautifully composed shots of the factory in operation and being dismantled, taken by cinematographers Yu Lik-wai and Wang Yu. While Jia's Still Life was haunting and quietly powerful, Useless seemed inexplicable and lazy. This is somewhere in between the two. Emotionally it has some import, but the mixed genre doesn't entirely work, and the sense of a Brave New World conveyed in Jia's diffuse but interesting The World seems to have given way to adverts for capitalism. Is this so that Jia can work and travel freely and get his films shown at home? The leading Sixth Generation Chinese filmmaker may be slowly morphing into somebody else.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-15-2020 at 02:41 PM.

-

Jaime rosales: Bullet in the head (2008)

JAIME ROSALES: BULLET IN THE HEAD (2008)

ION ARETXE

Rosales moves in the direction of greater austerity: no dialogue

Rosales' Bullet in the Head (Tiro en la cabeza) is in his words shot more or less "in the working style of wildlife documentaries" about an apparently "normal guy"--specifically a tall, somewhat heavy-set middle aged Spanish guy--who appears to be going about his existence, hanging out with friends, using the ATM, having sex with a girlfriend, buying a newspaper, chatting with a shopkeeper, listening to music in a CD store, attending a dinner party, making a call from a pay phone. Then he goes on a drive with another guy from Spain into France. There, abruptly, he and the other guy run out of a cafeteria where they are eating with a woman, chasing two young men. They trap them in their car and shoot them. Then they split up, the main guy with the lady friend stealing a car from a woman and taking it to a woods where they leave her tied to a tree.

Rosales was inspired by a news story last year about three members of the Basque separatist group ETA who killed two policemen in France in "an accidental encounter."

The festival blurb describes Bullet in the Head as "a claustrophobically intense, avant-garde thriller. We ...see and hear everything from a distance," the blurb goes on, "forced to assemble the movie's disparate narrative pieces for ourselves as we go along, like detectives on the trail of a dangerous conspiracy. Who is this man and who are his associates? And what are they plotting? A mystery movie in the purest sense, the remarkable Bullet in the Head will keep you pinned to the edge of your seat from its beguiling opening frames all the way to its startling conclusion."

Though admirers of the director--who won prizes in Spain for his fly-on-the-wall approach in Solitary Fragments/La Soledad last year--may find favor here again, this is a concept film that fails to live up to its festival blurb, and therefore leaves some viewers feeling chaeted. To begin with, there is one little detail this description leaves out. Though the film has lots of ambient noise, there is only one moment in the whole thing when there is any dialogue. That's when the two men run out to the parking lot after the two young guys they've spotted: one of the men says "f---ing cops!" That's it. "Forced to assemble the movie's disparate narrative pieces for ourselves"? We cannot. We never learn who any of the people are. This film, very quickly becomes numbingly boring to watch. It's like seeing through the eyes of a surveillance camera. But even that is not done convincingly, if these are meant be seen as the observations of, say, a detective. It is all shot in good looking 35 mm. Though the main character is seen from a distance, the positions from which he is observed are not particularly plausible for a detective doing a surveillance. It's just weird long-lens camerawork, without sound. You could make up a series of stories about the people and the protagonist's activities, but why bother? Anything would work. There is no "mystery" and there is no solution. It all leads up to a senseless act. Rosales says that in the news story the ETA men killed the police "in an accidental encounter." That doesn't quite fit with what happens here--or maybe it does; it depends on what you mean by "accidental encounter." Evidently the ETA men think the two young men--who could be cops--are following, or watching them. But then the cops--if that's who they are--leave the cafeteria. In fact they're sitting not too far from the ERA guys, eating and chatting normally. Odd behavior if they were following the ETA guys. So if the ETA guys go out and kill them, it's sheer paranoia. So the events are not so much mysterious as inexplicable, and this is not the way a thriller or a mystery works. This is more like a conceptual art piece that might be exhibited in a museum, though somehow it would seem pointless even in that context.

Not every film that is "different" is so for any purpose. Those who come to see this in a festival will feel cheated. That happens sometimes, perhaps because occasionally the blurbs for festival films are written by people who have not seen the films, or who have overactive imaginations. For Spanish viewers, who might detect Basque undertones, it might be more exciting. But that is speculation. For the general viewer, it seems a cheat, something that may be fun to debate for a while, but nothing you'd want to recommend to anyone--unless they made liberal use of the Fast Forward button. Remember how Truman Capote said of Jack Kerouac, "That's not writing; it's typing"? "This isn't filmmaking', some will say; " it's filming. Bullet in the Head has some conceptual interest, but seems a dead end.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-30-2009 at 01:17 AM.

-

Mike leigh: Happy-go-lucky (2008)

MIKE LEIGH: HAPPY-GO-LUCKY (2008)

EDDIE MARSAN, SALLY HAWKINS

A mellowed Mike Leigh, at 65, produces his definitive anti-miserabilist statement

Another one of Mike Leigh's remarkably fluent films made with his well-developed working method, which includes a long period of improvisation and development of back-stories during which, he pointed out at the NYFF Q&A, the actors are paid, and the characters are created and shaped, with surprises all along the way.

Poppy (the superb Sally Hawkins) is the "happy-go-lucky" protagonist, a thirty-year-old English girl who teaches elementary school and lives with Zoe (Alexis Zegerman), her roommate and pal of a decade's standing. Poppy has a wonderful, positive spirit. Am I wrong in thinking that this is particularly striking in the phlegmatic world of the English? She's no Pollyanna. She just chooses to react to things with good humor. In the opening sequence while trying to cheer up a grumpy, leaden-spirited bookstore clerk (Elliot Cowan), she gets her bicycle stolen. It disappoints her ("I didn't even get a chance to say goodbye"), but she quickly moves on and takes the bus or walks, and decides to take driving lessons.

This is the audience's basic introduction to Poppy's attitude to life. Clearly Poppy doesn't encounter sunshine whereever she goes (though this is summer in London, and the weather is nice). Leigh sees this film as his answer to his branding as a "miserabilist." It can be seen as the diametric opposite of Leigh's 1993 Naked. He wants it clear that it's his working method that's unchanging. His tone and characters are something new each time. Sally Hawkins' resolute smile sets the tone clearly here, along with her style of dress, which a writer has dubbed "garish grunge," framed on Fuji color film stock that provides opulent tones in the primary range within the bright format of Cinemascope--a new medium for Leigh.

A fateful decision, this choice of driving lessons, since it introduces Poppy to Scott (the droll, excellent Eddie Marsan), who becomes her instructor. He's phlegmatic, alright, and messed up. For a start, he's a racist who hates multiculturalism and locks the doors when he sees black people outside the car. Poppy takes the lessons as a lark, which bugs Scott enormously. He thinks her not serious, her insistence on wearking high boots particularly annoying (and no doubt provocative). In time it emerges that he is fascinated by her and even begins to stalk her. Initially it might be thought that Scott is right to be annoyed at Poppy, that her attitude in the lessons is frivolous and almost childish. But why should one adopt a grim attitude? Later it seems more that her mistake is to continue, when Scott is so moody and abusive toward her. But it is her way to give people a chance. She doesn't give up on him till he's gone way too far. Working well in the stages of successive lessons (not to mention the deft editing) Marsan is seen to provide finely modulated performance. He is only serious and a bit stiff at first; his dysfunctional tendencies emerge only gradually with each successive lesson, moving toward a very gradual crescendo that is a model of Leigh's skill with actors and his filmmaking method.

Early on there's a night of clubbing at which Poppy and the less ebullient Zoe get rather drunk before the weekend. At the suggestion of Poppy's school superior Heather (Sylvestra le Touzel), she joins a Flamenco class. The teacher (Karina Fernandez) is another skillful portrait; these brief sequences are priceless and memorable.

While wandering around at night in an unidentifiable place Poppy encounters a tramp (the remarkable Stanley Townsend). This is where Poppy's capacity for outreach is stretched the farthest. The tramp appears to be talking in gibberish; Poppy is undaunted. And he can make sense when spoken to. When she asks, "Have you had your dinner?" He quickly answers "No." When she says "Where will you sleep tonight?" He says right off "In a bed." "Of course," she remarks. Somehow a meeting of minds and spirits occurs, even as the tramp goes off to relieve himself three quarters of the way through their meeting. As can happen in Leigh's films, the outcome of this scene isn't clearcut. He said in the Q&A that it has no plot point as "in a Hollywood film." But that it's significant is indicated by the fact that when Poppy gets home to the flat, she won't tell Zoe about it and keeps the encounter to herself. While we may have felt Poppy was in danger, she never does. the meeting is a sign of her inner strength and generosity of spirit, as well as her intuition with people of all kinds. Though it stands alone, this is a central scene in the film.

Poppy hurts her back and goes to a chiropractor called Ezra (Nonzo Anozie). His laying on of hands is successful, though flamenco class throws things off again a bit.

A violent boy leads to calling in a social worker, Tim (Samuel Roukin), who asks Poppy, hitherto for some time relationship-free, to go out on a date. This works very well. They talk silly nonsense to each other at a pub--improvised stuff about eyes--that shows they click, and when they go to bed at Tim's "humble abode," that goes very well too. When Tim shows up before Poppy's next driving lesson, however, Scott explodes and the lesson turns into a tirade where he endangers them both with his emotional driving and craziness. This is the film's most violent confrontation and forces Poppy to terminate the instruction.

Leigh's turn to positivity may seem to lead us into some feel-good platitudes. But as the late David Foster Wallace said in his now famous Kenyan College commencement address, "in the day to day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance." The only thing is this. Leigh's method leads to great richness and depth, and Happy-Go-Lucky is a joy to watch for all but the most dysfunctionally negative of cool dudes (though it could have been cut by a few minutes). But the improvisational method doesn't lead to tidy conclusions. Things end with Zoe and Poppy drifting off in a boat, chatting about life. It's the texture of individual scenes that delights, rather than overall structure. At the same time, things are rounded out with a worldview. And Leigh's finely honed collective working methods make his films world class.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 02:01 AM.

-

Garardo naranjo: I'm gonna explode (2008)

GERARDO NARANJO: I'M GONNA EXPLODE (2008)

MARIA DESCHAMPS, JUAN PABLO DE SANTAIAGO

Bonnie and Clyde meet Pierrot le Fou: the Mexican nueva Nouvelle Vague is still alive

Naranja's movies, judging by this one and his previous one, Drama/Mex, which I saw a the London Film Festival, are full of sympathy for rebellions kids in his native Mexico and have an omnipresent sense of danger and the unexpected. This one, Voy a explotar, part of the New York Film Festival slate for 2008, is a romantic but playful drama of teen angst, escape, games that turn dangerous. It's a buddy picture of young lovers who rarely make love, who're indifferent yet adore each other. It's a road picture about runaways who, one of them, the smooth, dark-skinned Roman (Juan Pablo de Santiago), being of the privileged classes (his father's a successful politician, married to a second wife), never really hit the road. They escape from view while remaining at home. At Roman's home, that is, hiding out on the roof, where his father doesn't think to look for him--and where they can look down with contempt on the bizarre and silly reactions of the adults.

Maru (Maria Deschamps, more formidable than pretty) is in the same school but her mother is only a nurse. Maru is a misfit at school. "I'm gonna explode" is a line from her diary, from which she reads in voiceovers. It's how she feels sometimes. When Roman presents a "performance" piece at the school talent show entitled "I'll Meet You in Hell," in which he stages himself in a mock hanging, Maru gets it, and they bond in school detention. She's a misfit and an intellectual; he's a rebel desperate for his busy father's attention. His idea is to steal a car and run away from this small town to Mexico City. He pretends to abduct her at gunpoint, and they disappear, but instead of running away they pitch a tent on the roof of his house--where the view of the city is beautiful and they rend their private air with loud music heard through shared headphones. The inside of the tent is shot with a red filter and it's a warm place, at once womb-like and dangerous, since it is a place for scary sexual exploration: they're both virgins, or so it would appear, and are ambivalent about taking the plunge. Inside this warm space they sleep together and cuddle up under the covers, one or the other alternately out of sync by wanting to sleep late.

They sneak down for a blender, a barbecue, food, tequila, wine. Roman wants to make love but they keep putting it off, and in his willingness to do this a certain tenderness and comradeship grow up between them. Still, they get bored with their isolation and each other. Their escape is lazy yet every moment remains full of the danger of their being caught, especially when they go below, not knowing when his father will return. And there are often a lot of people down there, including relatives of both families and the police.

Eventually when they've conned his father and stepmother and entourage into going away, they sneak down into the master bedroom and make love at last, the long-awaited experience heightened by the danger or risking discovery again.

Later Roman's stepmother (Rebecca Jones, a good actress in this minor role who looks a bit like Mercedes Ruehl) climbs up and sees them making love on the roof. She keeps the secret, even though the kids' disappearance is all over the news and there's a police search on, spurred obviously by the importance of Roman's rich, right-wing father Eugenio (Daniel Gimenez Cacho)

Roman is far more fatalistic. If they could push a button and eliminate the world, she wouldn't, but he would. He has developed a penchant for firearms and wears a pistol in a holster rakishly slung over his shoulder at all times, even when they go about in casual outfits, pajamas and shorts. They strike poses and try on costumes--and hats--like a real Bonnie and Clyde. When they finally hit the road, she wears one of Roman's mother's long white dresses.

When everyone's away they hear somebody yelling from below and, lowering a plastic bucket, receive an invitation to his deputado dad to attend a gala Quince Años celebration in Santa Clara. They steal a car and go. Roman turns out to be a terrible drunkard. Later, when they'e in a field the car is seized and they flee separately in terror; they've pledged to reassemble at a certain meeting place. Things finally have an air of desperation once they're separated. It was the two of them against the world, so when one is gone, there's nothing. This is the classic absolutism of all romantic love stories from Majnoun Layla to Werther but the irony is that their relationship always remains as much accidental as it is romantic.

Back on the roof one last time after a sojourn with the one adult he trusts, a guy he calls The Professor, Roman has grown paranoid and rigged up a trap with trip wires and a loaded weapon. This backfires, and the game ends tragically.

Shown at the festivals of Venice, Toronto, and New York, I'm Gonna Explode is original in its combination of edgy rebellion and spoiled upperclass pouting. The movie was co-produced by Pablo Cruz along with Gael Garcia Bernal and Diego Luna, the pair of pals who gained international attention with Alfonso Cuaron's Y tu mama tambien; more polished now with beautiful visuals and fine acting, Naranjo's work still has the kind of raw energy and freshness we saw in the early efforts of Cuaron, Inarritu, and Del Toro--not to mention Carlos Reygadas, whom Naranjo declared in a NYFF press conference to be the greatest director working in Mexico today.

US release: 14 August 2009.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 02:03 AM.

-

Steven soderbergh: Che (2008)

STEVEN SODERBERGH: CHE (2008)

BENICIO DEL TORO

Guerrilla struggles that work, and don't

Ironically the most talked-about American film in the New York Film Festival is 98% in Spanish. The extra-long film's controversy began at the Cannes Festival. There were love-hate notices, and considerable doubts about commercial prospects. As consolation the star, Benicio Del Toro, got the Best Actor award there. I'm talking about Steven Soderbergh's Che, of course. That's the name it's going by in this version, shown in New York as at Cannes in two 2-hour-plus segments without opening title or end credits. "Che" is certainly appropriate since Ernesto "Che" Guevara is in almost every scene. Del Toro is impressive, hanging in reliably through thick and thin, from days of glorious victory in part one to months of humiliating defeat in part two, appealing and simpatico in all his varied manifestations, even disguised as a bald graying man to sneak into Bolivia. It's a terrific performance; one wishes it had a better setting.

If you are patient enough to sit through the over four hours, with an intermission between the two sections, there are rewards. There's an authentic feel throughout--fortunately Soderbergh made the decision to film in Spanish (though some of the actors, oddly enough in the English segments especially, are wooden). You get a good outline of what guerrilla warfare, Che style, was like: the teaching, the recruitment of campesinos, the morality, the discipline, the hardship, and the fighting--as well as Che's gradual morphing from company doctor to full-fledged military leader. Use of a new 9-pound 35 mm-quality RED "digital high performance cine camera" that became available just in time for filming enabled DP Peter Andrews and his crew to produce images that are a bit cold, but at times still sing, and are always sharp and smooth.

The film is in two parts--Soderbergh is calling them two "films," and the plan is to release them commercially as such. First is The Argentine, depicting Che's leadership in jungle and town fighting that led up to the fall of Havana in the late 50's, and the second is Guerrilla, and concerns Che's failed effort nearly a decade later in Bolivia to spearhead a revolution, a fruitless mission that led to Guevara's capture and execution in 1967. The second part was to have been the original film and was written first and, I think, shot first. Producer Laura Bickford says that part two is more of a thriller, while part one is more of an action film with big battle scenes. Yes, but both parts have a lot in common--too much--since both spend a large part of their time following the guerrillas through rough country. Guerrilla is pretty much an unmitigated downer since the Bolivian revolt was doomed from the start. The group of Cubans who tried to lead it didn't get a friendly reception from the Bolivian campesinos, who suspected foreigners, and thought of the Cuban communists as godless rapists. There is a third part, a kind of celebratory black and white interval made up of Che's speech at the United Nations in 1964 and interviews with him at that time, but that is intercut in the first segment. The first part also has Fidel and is considerably more upbeat, leading as it does to the victory in Santa Clara in 1959 that led to the fall of the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba.

During Guerilla I kept thinking how this could indeed work in expanded form as a quality European-style miniseries, which might begin with a shortened version of Walter Salles's Motorcycle Diaries and go on to take us to Guevara's fateful meeting with Fidel in Mexico and enlistment in the 26th of July Movement. There could be much more about his extensive travels and diplomatic missions. This is far from a complete picture of the man, his childhood interest in chess, his lifelong interest in poetry, the books he wrote; even his international fame is only touched on. And what about his harsh, cruel side? Really what Soderbergh is most interested in isn't Che, but revolution, and guerrilla warfare. The lasting impression that the 4+ hours leave is of slogging through woods and jungle with wounded and sick men and women and idealistic dedication to a the cause of ending the tyranny of the rich. Someone mentioned being reminded of Terrence Malick's The Tin Red Line, and yes, the meandering, episodic battle approch is similar; but The Thin Red Line has stronger characters (hardly anybody emerges forcefully here besides Che), and it's a really good film. This is an impressive, but unfinished and ill-fated, effort.

This 8-years-gestating, heavily researched labor of love (how many more Ocean's must come to pay for it?) is a vanity project, too long for a regular theatrical release and too short for a miniseries. Radical editing--or major expansion--would have made it into something more successful, and as it is it's a long slog, especially in the second half.

It's clear that this slogging could have been trimmed down, though it's not so clear what form the resulting film would have taken--but with a little bit of luck it might have been quite a good one.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 12:35 AM.

-

Joao botelho: The northern land (2008)

JOAO BOTELHO: THE NORTHERN LAND (2008)

ANA MOREIRA, JOAO BOTELHO

Painterly mysteries of five generations of women

This film by the Portuguese director Joao Botelho (A corte do norte) is a handsome adaptation of a 1987 novel by Agustina Bessa Luis, a multi-generation exploration of a wealthy family with a mysterious past and a house on the island of Madeira. A young woman becomes obsessed with finding the true story of a distant ancestor, a noblewoman who scandalized society. She explores the stories of various women, all of whom played out their frustrated passions on the island in large estates set along magnificent, wind-swept coastal places. One hanged herself. Another threw herself off a cliff into the sea and disappeared. Each of them, spanning five generations, from 1860 to 1960, is played by the actress Ana Moreira, who has seven different roles in the film. The younger descendant becomes distraught when she thinks she has discovered her grandmother was a whore. Or was she a famous actress? This central figure, Emilia de Sousa, was inspired by actress Emily das Neves, the first Portuguese theatrical superstar. The film constantly shifts back and forth through time and across generations as it tells its tale.

This is a magnificent-looking film whose scenes are often presented as striking tableaux of multiple figures in ornate costumes. It's another example of very sharp, very handsome-looking digital imaging. The lighting is dramatic and often chiaroscuro, and the colors are rich and evocative of 19th-century painting. The music is chamber and classical. The Northern Land is elegantly crafted cinema in an old-world European tradition using new technology. The difficulties presented to a viewer unfamiliar with the language and the novel source are many, however. The subtitles are complete and literal, which means they are long and many, and they are small and ornate in font and thus doubly difficult to read. The story is difficult to follow, and hence difficult to relate to. The virtuoso performance of Ana Madeira is one of the beauties of the film, but does not make it any easier to decode. On first viewing, these painterly mysteries remain pretty much darkly mysterious.

Other important cast members include Aibeo Ricardo, Rogerio Samora, Marcella Urgeghe, Antonio Pedro Cerdeira, ustodia Galego, Diana Costa e Silva, Fernanda Borsatti, Filipe Vargas, and Graciano Dias.

This is a new film that will be released in Portugal in 10 theaters as part of a tribute to the author that will include a reissue of the novel and a book of photographs giving the screenplay and a discussion of Botelho's work of adaptation. Botelho was previously represented at Lincoln Center in the New Directors/New Films series with his film A Portuguese Farewell/Um Adeus Portugues in 1985, and at the New York Film Festival with Hard Times/Tempos Dificeis in 1988. This appears to be the premiere of The Northern Land (at the Ziegfield Theater, the NYFF's main venue for 2008m at 9:15 p.m. September 30).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 12:43 AM.

-

Olivier assayas: Summer hours (2008)

OLIVIER ASSAYAS: SUMMER HOURS (2008)

EDITH SCOB, CHARLES BERLING, JEREMIE RENIER

A splintering world, from the French point of view

Assayas says this film more or less sums up all his work so far, and that may surprise some, since it is so different from his previous work but like the work of other more conventional French filmmakers who deal with middle class life. The impulse behind the film was something occasional and seemingly trivial, a request from the Musée d'Orsay to do something, as they'd asked Hou Hsiau-hsien (the result was Hou's Flight of the Red Balloon). Hou's film uses the d'Orsay so incidentally, I can't even remember how it fits in; but Assayas takes the idea of a museum quite seriously and literally. His story is about a family, and a mother who dies in her mid-seventies leaving behind a house and a collection of museum pieces, works of art, furniture, and fine objects that the family has to decide how to deal with.

We begin with a scene quite conventional in French films: the seasonal family gathering. The Heure d'été (summer hour) is a moment when adult siblings Adrienne (Juliette Binoche--the star of Hou's Balloon, though including her was not a d'Orsay requirement), Frédéric (Charles Berling, his third time in an Assayas film, and a kind of alter ego for the director), and Jérémie (Jérémie Renier) with parts of their families, have come together at the family's beautiful country place to celebrate the 75th birthday of their mother Hélène (Edith Scob). Hélène, who lives in the house, is still one of those perfectly slim, elegant, erect French women, but spends a lot of time talking to Frédéric about her death and explaining, to his annoyance, about the valuables the children will inherit when she dies--a handsome 19th-century desk by a famous desigmer; a display case from the same hand; and other precious objects, including the sketchbooks of her famous uncle, the artist Jean Berthier; two Corot paintings; and two large and unusual sketches by Odilon Redon. They will want to dispose of them all, she says, and the house. Frédéric loves her, the house, and the objects, and doesn't want to hear this. But she has certain requirements. The D'Orsay wants the furniture; the sketchbooks must be kept together. Some things she is giving to him.

After this sequence, time has passed, it's perhaps a year later, and Hélène is dead. She has gone to San Francisco for the start of a major traveling exhibition of Berthier's work, and there has been a presentation in France on his personal life (including the fact that he was gay, and other controversial information) which shook her considerably. And her involvement in the production of a book, a catalog, and the traveling exhibition all wore her down and left her devastated and empty when they were completed.

It is against Frédéric 's wishes, but when the siblings meet again, it's obvious Hélène was right and the possessions and the house must be sold, and the old housekeeper, Eloise (Isabelle Sadoyan) must be released. Jérémie, who works for a company that makes running shoes, is going to take his wife and kids to live in China permanently. Adrienne, who is a designer, lives in New York, and she's going to marry her American boyfriend and stay there. They can't go back to the country house regularly any more. It seems Frédéric gets a raw deal, because he, whom the dispersal of family heirlooms hurts the most, is going to have to handle all the nuts and bolts of the process, because he's the only one who lives in France. But that's the way it is, and what's more Jérémie needs money to set up in his new life in China.

Assayas goes into the details, even showing a meeting of the curators and administrators concerned with the donation at the Musée d'Orsay. They are particularly interested in the furniture and the Redons (the Corots are sold elsewhere). One official objects that these things will just go into storage.

This is a suavely composed picture, but it still comes across as the most elegant of instructional films, if such existed for showing at posh schools to teach children of the wealthy how to deal with inheritances in the world of globalization. Yes, globalization is what Assayas is talking about, though the word is used in his comments on the film, not in the screenplay itself. It is not necessarily true that this film is more didactic than Assayas' other works; its didacticism is admirably straightforward, and at the same time, the ideas are presented in what for Assayas is an unusually warm context. One of the touchstones is the old housekeeper, Eloise, who returns to the house when it's been shut up, and goes to Hélène's grave to deposit flowers. The important point is that this is not about the traditional family squabble over inheritance. Though Frédéric is saddened, there is no argument, and he and Jérémie pointedly (maybe too pointedly) part friends. There are other little details that are accurate and practical. It's pointed out that Adrienne's plan to sell the sketchbooks in New York through Christie's won't work. The French government is unlikely to let them out of the country, and anyway, Christie's would want to sell the sketches off page by page, going against Hélène's intention that they be kept together. Frédéric is away a lot too, and for whatever reason he has to pick up his teenage daughter (Alice de Lencquesaing), caught stealing, and holding pot. But the final scene, which again is warmly didactic, shows that daughter with her boyfriend and a bunch of her friends (the 'summer hour' come again) invading the old house one last time to have a big party, play loud music dance, and celebrate. But the daughter takes her boyfriend to see a special place on the land (it's a Proustian, Swann's Way kind of moment) and she cries, for her lost youth, and for the family heritage that a splintering modern world is taking away. People, Assayas pointed out in a NYFF Q&A, have a greater breadth of knowledge of the world now, but they pay for that by losing the deeper understanding of personal traditions one used to have.

As I'm not the first to comment, this is one of Assayas' simplest films, but it's also one of his most touching and meaningful. Instructional film though it may be, it deals with subject matter that can move the hardest heart. If you don't care about losing a parent, you will surely be touched with the thought of losing the places of your childhood--and family money. If love won't get you, money will. And there is a final meditation by Frédéric at the D'Orsay where he and his wife Lisa (Dominique Reymond) look at the objects they've donated (not in storage) and consider the other trade-off: a contribution to history and the public's culture has been made, but the objects are like prisoners now, shut up in a cold space, robbed of their human context in a family's life.

This isn't finally the way I expect a "conventional" French film of bourgeois family life to be, but in its combination of rigor and warmth, it may come to seem rather wonderful. At least its straightforwardness and its fine cast make it most appealing.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 12:37 AM.

-

Darren aronofsky: The wrestler (2008)

DARREN ARONOFSKY: THE WRESTLER (2008)

EVAN RACHEL WOOD, MICKEY ROURKE

Charisma, heart, and hard work make a comeback of a has-been

Billed as Mickey Rourke's big comeback, this film is the finale presentation of the New York Film Festival 2008. Awarded in Venice and shown at Toronto, it features a winning performance by Rourke. It's a simple story, a mixture of raw authenticity and old fashioned corn about a washed up professional wrestler who's 20 years past his prime and resists admitting it till he has a heart attack and is forced t turn to the only two people he has in his life, a lap dancer and an estranged daughter. It's pretty monochromatic and claustrophobic, but the tiny framework shows off Rourke's generous, authoritative performance. Rourke's weathered, soulful face and sweet-sad smile sell the movie.

Early scenes establish that Randy 'The Ram' Robinson (Rourke), who has long graying bleach-blond hair and wears a hearing aid, still has fans from his heyday in the 80's and warm contacts in the pro wrestler community of today, who give him work on weekends. He's well liked (kids in his neighborhood clamor around him), and takes life's hard knocks with patience--and that smile.

But all is not well. The first night we see him after a fight locked out of his trailer because he owes the manager money. He lives alone, has a shaky relationship with a lap dancer, work name Cassidy (Marisa Tomei). His lesbian daughter Stephanie (Evan Rachel Wood), who's in school, despises him for not being there when he was needed. We're in the world of numbed pain and charred, sealed-away emotions here.

The second evening of fights pits the Ram against an S/M wrestler who uses a staple gun on him, and broken glass, and barbed wire. Ram collapses after this fight and wakes up in intensive care after a bypass operation. The hospital is the real beginning of the film, though Rourke and the filmmakers are over-committed to the wrestling scene, and stage more painful and realistic bouts, in which all the fighters other than Rourke were professionals.

Ram realizes he's not the man he was. The doctor has told him he can't wrestle any more. He tries to jog and can't. Helpless and alone, he turns to Cassidy (whose real name is Pam), but she is reluctant to admit he's more than a customer. He visits his daughter, but she is extremely hostile. In just a couple scenes, Evan Rachel Wood is raw and powerful. Tomei is authentic too, having mastered the lap-dancing technique and assimilated its world's mix of sensuality and distance. Rourke/Ram's encounters with both women are painful and memorable.

There's a good sense of context, even though Ram's world as shown is narrow. "The 90's f----ing sucked!" he exclaims to Cassidy when he finally coaxes her into having a beer with him outside the club. He hates that bastard Kurt Cobain. Axel Rose was The Man. You realize she's as washed up as he is. She has a 9-year-old kid and wants to quit and somehow get into a condo.

The screenplay by Roy Siegel, an original editor of The Onion, has lightness and humor to undercut the melodrama and doom. Ram is a laugh when, after the heart attack, he starts working longer hours at the Jersey Dollar's deli counter, doling out potato salad and ham, joking with the man and flattering the women.

Finally after he is pushed away by Cassidy/Pam, on a bad day at the deli, Ram flashily quits and calls a promoter and countermands his resignations, saying the re-match with "The Ayatollah" is on again. The Aronofsky of Requiem for a Dream set a record for determinism, and it's hard not to see this Wrestler as doomed. But the filmmakers' and and cast's involvement in the milieu and Rourke's humility and charm undercut that enough so the final sequence is uncertain and interesting. And all the fights are good.

The title The Wrestler can be generic because unlike boxing films, wrestling ones are rare, indeed nonexistent. Rourke himself is a boxer; the switchover wasn't easy, but he had the athletic background, and not only that, the has-been life of his character, a washed-up star in an activity looked down on by all but rabid fans. Few think of it even as a sport, though it requires conditioning and skill and involves constant injuries. In the NYFF Q&A Rourke conveyed a sense of his respect for this activity as a sport, and Aronofsky reported that his work on the mat won the approval of the pros. If this is an iconic performance as some are saying, it's not just Rourke's personal identification with the character's comeback mode, but good hard technical work to make it all authentic.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 12:48 AM.

-

Clint eastwood: Changeling (2008_

CLINT EASTWOOD: CHANGELING (2008)

ANGELINA JOLIE, JEFFREY DONOVAN

A warped killer, a lost child, and a corrupt LAPD: what's not to like?

Changeling has a lot going for it in the eyes of the public just being directed by Clint and starring Angelina. Moreover the little-known but true LA story it tells is heartrending. A hard-working single mother in 1928, Christine Collins (Jolie) is forced to work on Saturday in her job as an assistant supervisor at Pacific Telephone and she leaves her young son Walter (Gattlin Griffith) at home. When she comes back he's gone. Five months later the police produce her son, found in another state--only she denies it's her son. The LAPD's reputation is on the line, and they force Christine to take the boy home. Then they try to discredit her as a lazy and unfit mother when she keeps insisting the kid isn't hers. Eventually she tangles more and more with the LAPD, who're going through an especially lawless period under a corrupt chief. They've shot down a lot of criminals in cold blood and swept away the bodies--just so the Force can control all the crooked dealings in town. Their arch-enemy and leader of the public outcry against cop corruption is crusading minister Rev. Gustav Briegleb (John Malkovich), who seizes upon the Collins case when it becomes public, smelling a rat. After Collins has repeatedly opposed the cops and refused to accept the boy delivered to her--who's three inches too short and circumcised, has different dental work and is unrecognized by his schoolteacher--a willful Irish Captain assigned to this case (Jeffrey Donovan) orders her locked away in a psych ward. A lurid story of child abductions emerges.

Changeling, in the screenplay written by J. Michael Straczynski, is based on contemporary press accounts of what are called the "Wineville Chicken Murders." The mystery of Walter Collins' disappearance vies with the story of police corruption and the secret of the murders for attention, but Strazzynski wisely tells the tale from the viewpoint of Collins' mother, a kind of feminist heroine, since at a time when women tended to keep their mouths shut, she will not be silenced and never gives up. Some of the more gruesome details of the Wineville story are omitted, but sequences that go there still have a horror movie cast to them. The rest is a thriller-cum-police procedural with distinct period sociological elements. But there is skillful handling in the way a far-reaching story begins and ends with the intimate experience of a bereaved mother.

Eastwood seems to have looked for a story on the order of Fincher's even lengthier Zodiac (this is 140 minutes), but the melodrama and focus on cop-crime in the material relate it to the James Ellroy-based films L.A. Confidential and The Black Dahlia. The psych-ward incarceration sequence takes you straight back to Samuel Fuller's Shock Corridor--at which point things are beginning to seem pretty lurid, and the film almost as manipulative as Fuller's. Nonetheless the style has Eastwood's usual current elegance and clarity. Oxymoron it may seem, but this film is an example of lurid restraint. After all, this is after all a tale in which manipulation is being consciously looked at. In an interview at the NYFF, Eastwood pointed out that there was a link with movies like Gaslight that deal with people trying to bend the minds of others: this is what the crooked cops try to force on Catherine, and they win to the extent that she takes the other boy home. And this is the most interesting and unusual aspect of the story.

The acting is confident, if varied. There are a bunch of young boys who turn in strong, convincing performances, and as manipulative police captain and his chief, Jeffrey Donovan and Colm Feore are reasonable, and Michael Kelley appealing as the good cop who unearths the kidnappings. Newcomer Jason Butler Harner gives a distinctive performance as the wigged-out killer, Gordon Northcott. Amy Ryan is typically strong as another victim of the cops' psych ward incarceration scam. Less successful is John Malkovich in Marcelled wig as the crusading religionist Rev.Briegleb: he just seems too mannered and creepy. Jolie is good, though her appearance is a bit strange: that huge mouth goes oddly with 20's hair styles. At one moment after she was out of the psych ward, I thought she might be locked up a second time--for overacting. Harner gets his chance to chew up the rug himself in his final scene. A little holding back would not have hurt.

The film is outstanding in its period look; and good, if not perfect, in its period feel. If nothing else you'll remember Catherine Collins quaintly gong back and forth along the lone line of phone operators she supervises--on roller skates. Whole neighborhoods were restored by the filmmakers and streets filled with Model T's and, best of all, old trolley cars. The attempt at period lingo might have been more consistent; but that's a goal rarely achieved. Since the time scheme runs from 1928 to 1935, more mention of the Great Depression surely would also have been in order. Since the screenplay sticks to known facts, there is nothing about Jolie's character before or after the events. This is a good and watchable film, but not up to Eastwood's terrific 2003, 2004 and 2006 efforts. Presented as the mid-point film of the New York Film Festival, already well-publicized at Cannes, Changeling opens nationwide October 31st. Eastwood has already directed two more films, one of which, Gran Torino, he stars in. At 78, Clint still seems unstoppable.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 01:15 AM.

-

Ari folman: Waltz with bashir (2008)

ARI FOLMAN: WALTZ WITH BASHIR (2008)

Recovered Israeli memories of the 1982 Lebanon war in animation arouse mixed feelings

What Ari Folman's calls his "animated documentary" follows a film director who's having trouble remembering a massacre that occurred while he was serving in the Israeli army during the Lebanon War in the early '80s. He tries to fill in the gaps by tracking down his old comrades. Eventually he recreates the Sabra and Shatila massacres as seen from his and his comrades' point of view.

The look and the content of this film are harsh and the emotional effect is ultimately powerful, though the subject most of the way though is the numbing down of Israeli veterans who have been involved directly or by proxy with the wholesale killing of Arab civilians. In combat revived memories show the soldiers like zombies, unaware of what they're doing, shooting in all directions without even choosing targets. In contrast to their numbness and indifference, the background music is as loud as an 80's disco; perhaps intentionally: the year of the war is 1982--the height of the disco era. Film music includes a chilling Israeli song that boastfully begins "I bombed Sidon/Beirut today...." For contrast, too often, a Bach keyboard concerto, the same one Glenn Gould used for the background of Slaughterhouse-Five in 1972, is blasted forth.

A lady psychiatrist the film director meets with tells him that soldiers' "disassociating" from combat horrors is a common psychological phenomenon. Ironically, the thing that makes one Israeli stop "disassociating" during the invasion of Beirut is entering the hippodrome and observing a massacre of Arabian horses. Mowing down humans didn't affect him.

The director also spends time on several visits with a pot-smoking comrade based in Holland who's become rich selling falafel (an Arab food, one might point out) and lives on a posh estate near Amsterdam. He and the director get stoned together and remember. Various other 40-something Israeli army vets appear--animated talking heads whose memories, when they come back, are also in turn animated and shown. One describes abandoning the invasion on his own, going AWOL in effect, and by doing so inadvertently surviving when most of his unit was wiped out by the Lebanese, while he lay hidden for a long time in a zone where all were presumed dead, then swimming in the calm ocean until, exhausted, almost unable to walk, he comes up on the beach and inadvertently rejoins his own regiment. He has previously repressed most of this experience because of thinking himself a coward who had betrayed his comrades.

The titular sequence concerns a particularly macho squad leader who in central Beirut under heavy firing, borrows back the automatic weapon he favors and goes into the street, dancing around, firing in all directions while snipers fire from above, yet surviving. At this time Bashir Gemayel, the new Lebanese President, had just been assassinated, which was taken as a signal for the Israelis to step up their attack. At this time they were allied with the Lebanese Christian Phalangist Militia. The Phalangists subsequently were allowed to go into the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps on the pretext that there were several thousand Palestianian "terrorists" still hiding there. They killed at least 800 Palestinian civilians, including women and children. The Israelis knew this, and did nothing. The film reports one soldier calling Ariel Sharon to tell him, and Sharon saying merely thanks for the information, happy new year.

This is the climax of the film, the massacre, seen from a safe distance, but with analogies to Nazi murders and the Warsaw ghetto and with a few seconds of live actual video footage of loudly wailing Palestinian women after the massacre going back to witness what has happened and saying over and over to the camera in Arabic (not translated) "Photograph this, bear witness!"

This animated film will appeal to some for its originality and specificity to the experiences of a few Israeli soldiers. It is probably also notable for the accuracy of its representation of the tanks and weaponry and uniforms of the Israeli army of the period. What gives it a bad taste for me is its totally Israeli focus. The concern is not so much the massacre as the guilt feelings of the Israeli soldiers for having allowed it to happen, and, most of all, on their repression of any sense of guilt or even memory of the 1982 Lebanon war. It is they who have suffered, in their eyes; the dead horses matter more than dead Palestinians. (They would perhaps not see this.)

One writer (Onion A.V. Club) with some reason links Waltz with Bashir, for its "dreamy, meditative rhythms," to Linklater's Rotoscoped Waking Life--and questions whether it would be of as much interest if it were live-action. In fact the value and point of the animation is that Folman can recreate the recovered memories of the soldiers--just as they remember them. He, that is the director, initially remembers absolutely nothing (But do actual film records exist? Surely they do). Perhaps the film is correct in not making any political point, perhaps not. It seems like raw material, the experiences it refers to still not fully digested and understood, the larger political context left undefined. This is of course a film that would be experienced very differently in various Israeli, Lebanese, or Palestinian settings, and might be wasted on some American audiences. Note the A.V. Club writer's question. But at least what we have here is a strong artifact, the only one in the New York Film Festival, of the torment that is Middle East politics.

The film is in Hebrew with English subtitles. Subsequent to its October showing in the NYFF it will be released by Sony Pictures Classics starting December 26, 2008.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 01:15 AM.

-

Wong kar-wai: Ashes of time redux (2008)

WONG KAR-WAI: ASHES OF TIME REDUX (2008)

TONY LEUNG KA FAI

A successfully gilded lily

This classic ultra-stylized and (in the words of the NYFF blurb) "insanely gorgeous" 1994 martial arts or wuxia film based on the Louis Cha novel The Eagle-Shooting Horses needs no introduction to film fans now, though before Tarantino’s release of Chungking Exrpess Americans had to go to Chinatown theaters or rent pirated videotapes to see it; I saw it in Chinatown in a double bill with As Tears Go By (1988). A cinematic icon today, Wong Kar-wai didn't get international recognition till 1997 at Cannes (for Happy Together), and the majority of US art-house goers didn't notice him till the theatrical release of In the Mood for Love (2000). Now ironically since the huge blowout of Wong's epic 2046 (2004), a summing up of his 60's nostalgia themes and characters, he seems prematurely to have reached a point of exhaustion, and his English-language romance Blueberry Nights (2007) was a critical failure. In this context his project of enhancing and re-editing Ashes of Time may be seen as another example of treading water; but it's still great to have it. Many have still not seen it, and any films as visually magnificent as Wong's are best seen in theaters as this one will now be. (It's also fortunate that all his films can be seen on decent DVD's now with readable subtitles for English speakers, instead of the weird earlier Hong Kong prints with flickering titles in Chinese and peculiar English that disappeared before you could read them. Ashes of Time Redux has the best English subtitles yet both visually and linguistically.)

According to Wong, Ashes of Time's negatives weren't in very good shape, and a search of various versions led him to a huge warehouse somewhere near San Francisco's Chinatown that contained the entire history of Hong Kong movies. He and his team put together various versions, adding a bit to what we probably know but cutting some dialogue, digitally cleaning up the images and enhancing some of the color and making many changes in the sound, adding a whole new score or "re-arrangement" by Wu Tong with cello solos by Yo Yo Ma.

Experts will have to comb over all this to explain and elucidate and evaluate the differences. The cinematographer Christopher Doyle, who was present at the press screening of the film at the NYFF (as were Lin and Wong), said flat out that he doesn't like the color "enhancing" bits--and neither do I. A lot of yellows and oranges are heightened, greenish-turquoise touches are set in, and many of the desert sand landscapes seem to have lost their surface detail. This seems unnecessary and even obtrusive. But such changes are not pervasive enough to spoil the generally magical visual experience the film provides. Other images simply look more pristine and clear; in particular Maggie Cheung, with pale face and red dress in shots long dwelt upon, looks more haunting and luminous than ever. At the NYFF screening, Wong declined to say anything about what specific changes were made in the editing. He preferred to talk about how he adapted Louis Cha's novel and how this film relates to his oeuvre. Both for him and for Doyle it was an essential milestone. Featuring the late Leslie Cheung, both Tony Leungs (Chiu Wai and Ka Fai), Jacky Cheung--and with Carina Lau as Peach Blossom, the poor girl who hires the Blind Swordsman to revenge her brother's death; with Maggie Cheung as The Woman, and with martial arts film great Brigitte Lin as Murong Yin and Murong Yang, the sister and brother. Lin, now retired, was responsible for the revival of the wuxia genre and is central to this film, though Maggie Cheung is its diva, its dream lover.

Cha's novel is a complicated 4-volume genre epic, very popular but little known or appreciated in the West. Wong studied it carefully (and made a parody of it called Eagle-Shooting Heroes) but then though he says this film unlike all his others had a fixed plan (and thus that made for a story uniquely full of fatalism), he threw away Cha's plot and just took a couple of the main characters and made up another simpler narrative imagining what the characters' lives were like when they were young. Simpler perhaps, but seemingly incomprehensible. But after this re-watching I see it does really have a coherent narrative; it's just intricate and, above all, cycliccal, confusingly looped in on itself. It ends as it begins, with the narrator looking into the camera and speaking the opening lines.

As Zdac, a perceptive IMDb user, comments, "One thing to love about this movie is the way that director Wong Kar-Wai takes the reflective internal monologues and quirky, alienated losers from his other films and transposes them to the world of Chinese heroic fantasy. It's an interesting idea that both ennobles and deconstructs the genre. "

Ashes of Time was shot in the desert. Doyle had never done that. The film was long delayed and the shoot was difficult. Doyle knew nothing about martial arts or Jianghu, the parallel universe of martial arts fiction. He was under extreme constraints, having very little artificial light. Nonetheless he produced some of the most beautiful sequences in modern film, because he's a great cinematographer, perhaps the greatest of recent decades, as Wong Kar-Wai is one of the defining contemporary cinematic geniuses.

Wong is notable for his meditative and arresting voice-overs, and they're ubiquitous here: there is more talk than fighting. Here is a sample: "People say that if a sword cuts fast enough, the blood spurting out will emit a sound like a sigh. Who would have guessed that the first time I heard that sound it would be my own blood?"

"You gained an egg, but lost a finger. Was it worth it?"

There are aphorisms or bits of advice: "Fooling a woman is never as easy as you think."

It's lines like these that define the film's special combination of humor, chutzpah and noble fatalism. But as the Redux version makes clearer than before, the film is primarily anchored and structured by its grounding in the Chinese calendar. The Chinese almanac is divided into 24 solar terms and the narrative moves forward selectively through these terms, which (naturally, being chapters in an almanac) contain weather descriptions, and advice as to what is propitious or unlucky, and in what regions and directions. New inter-titles in this version add to the emphasis on this solar-calendar structure. There is also a great deal about oblivion and forgetfulness (which are linked with wine, including a magic wine that eliminates memory). The desert and drinking are visual touchstones throughout as are pairs, opposites, and contrasts; and there is cross-dressing and perhaps bisexual love. The images are full of flickering light--figures shot by Doyle through a huge intricate wicker basket are particularly mesmerizing. The shadows from that basket may seem gratuitous, but only as Cezanne's apples are gratuitous.

The sword fights, which do not begin until a long way into the film, are for the most part without the acrobatic feats actually performed or digitally faked as in current martial arts films, though they are elaborately staged by the action choreographer Sammo Hung. They are a symphony of fast cutting, closeups, blurs, and slow motion (which Wong intended particularly to express the fatigue of the Blind Swordsman in the film).

Derek Elley of Variety thinks the alterations, notably the new non-synth musical accompaniment with a "heavier" western classical sound; the inter-titles; the dialogue cuts and the addition of Lin's own voice in her Mandarin dialogue, "have the effect of taking the pic out of the period in which it was made and giving it a look and feel that was largely alien to Hong Kong cinema of the mid-'90s." This seems to me irrelevant, since Wong's take on the genre was already highly original, and the film still seems very much itself and even more so, and, except for the occasional excesses in color "enhancement," this is a very fine re-release. Devotees can always go back and watch their copies of the earlier version on tape and DVD. Part of the New York Film Festival, this is a Sony Pictures Classics release opening in US theaters starting October 10, 2008. Don't miss it! Don't worry about understanding it. Later you can read all about it in a book, like Stephen Teo's Wong Kar-Wai: Auteur of Time (2005). Meanwhile, just drink in the images and sound.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-23-2020 at 06:39 PM.

-

Hong sang-soo: Night and day (2008)

HONG SANG-SOO: NIGHT AND DAY (2008)

KIM YUNG-HO, PARK YUN-HYE

A Korean lost in Paris A Korean lost in Paris

Hong Sang-soo, whose films have been frequently featured at the New York Film Festival, weaves tales of men and women wandering in and out of relationships and doing a lot of talking about them. He's a kind of South Korean Eric Rohmer, except that his men and women aren't quite as ostentatiously presentable as Rohmer's and his men have an (often gently satirized) gauche sense of macho entitlement that's more Korean than French. A debt to the New Wave is nonetheless there, but Hong hasn't ever actually sent his characters to Paris as Tsai Ming-Liang and Hou Hsiau-hsien have--till now.

The protagonist of Night and Day/Bam gua nat, Sung-nam (Kim Yung-ho), is a 40-something Seoul painter of cloudy landscapes who smokes pot with some American visitors to Korea. One of them gets caught, and mentions Sung-nam's name, and he has fled abruptly to Paris. The film unreels as a day-to-day account of his sojourn, which includes involvement with a bunch of fellow countrymen and in particular several attractive younger women. Sung-nam being a rather naive, un-suave, and clueless person of decidedly rumpled good looks, his success with the other sex is a little surprising, but he's a typical Hong Sang-Soo male. He knows not a word of French, and is uncomfortable trying to buy a condom in a pharmacy, an inconvenience that leads to others.

What propels Night and Day most of the way is its sense of specificity and anecdotal observation. Sung-nam stays at a kind of Korean hostel presided over by a diminutive older man, Mr. Jang (Go Ki-bong), who offers Sung-nam comfort at moments of stress. Sung-nam drifts from day to day at first, just hanging out and meeting some of the other Koreans in Paris, who tend to all know each other--and reading a Bible, which happens to be there and which he says he takes just as a story. Notably he runs across Min-sun (Kim Yu-jin), whom he runs after, knowing she looks familiar. Absurdly, he's forgotten that he was in a passionate affair with Min-sun years ago. She's now living in Paris and married to a Frenchman. She's not at all pleased with Sung-nam's memory lapse, but nonetheless willing to talk to him.

Eventually Sung-nam takes Min-sun to a hotel room where she takes a shower and is ready to have sex, when he begins quoting from the Bible and expresses misgivings. No sex.

Meanwhile Sung-nam calls his wife in Seoul frequently, and they both declare how much they miss each other. She says she'll ask his mother to give her money so she can come and stay with him. There is an air of mutual desperation about their conversations, but above all he seems in limbo, unable to make a decision.

Mr. Jang introduces Sung-nam to a Beaux-Arts student named Hyun-ju (Seo Minjeong), but he is more interested in her thinner and prettier roommate, Yu-jung (Park Yun-hye). Sung-nam is comically inept and forward with these women, hanging around and forcing himself upon them, and yet Yu-jung succombs, and Sung-nam takes her to Deauville (their second trip, but this time without Hyun-ju). Once again as in Hong's Woman on the Beach there are conversations on a cold empty stretch of sand resort beach, only it's actually early October, and Sung-nam never has to wear anything but shirtsleeves. And essentially again it's a shy-aggressive man torn between two women.

Sung-nam also is at a dinner where he naively is shocked that one person is from North Korea. He is confrontational, and as a result is forced to beat a hasty retreat. He also meets the best known Korean artist living and practicing in Paris, and feels ashamed at having suspended his own career with this sojourn. The movie's scenes often end with some mild debacle or a sudden departure, usually with mildly comic effect. At the same time that Sung-nam's various prospects for a Paris love-life, he seems (in his phone conversations with his wife) to be all the more filled with a sense of desperation and confusion; it's as if he's increasingly aware that he's living the kind of Paris adventure a young Asian artist might better have had at 20 or 30 instead of 45, and this isn't going to work. Eventually surprise news leads Sung-nam to return to Korea and his wife (Hwang Su-jung), and he faces the consequences of the pot incident and, not without some bumps along the way, begins to resume his life.

The recurrent theme from Beethoven's Seventh Symphony gives a surprise note of European high culture and perhaps further irony, but it seems pushed a little too hard.

Night and Day remains interesting and textured as Hong Sang-soo's other films, but at 144 minutes it's longer than it has any justification for being, and the touristic aspect and an obtrusive use of the zoom lens seem out of character. Every scene is interesting, but they go in a few too many directions, and pursue too many strands. Tightening up and paring down would have added significantly to quality. It's as if Hong was distracted by the European sojourn himself. Maybe the director would do better to stay at home next time. Nonetheless Hong is an auteur well worth keeping track of. NYFF--no US release pending. It opened in Paris in July--along with Woman on the Beach--and was reviewed at the Berlinale earlier in the year.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-03-2019 at 01:19 AM.

-

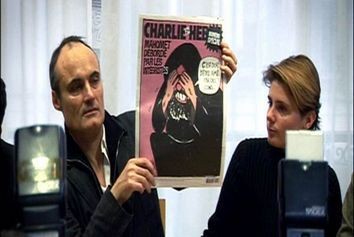

Daniel leconte: It's hard being loved by jerks (2008)

DANIEL LECONTE: IT'S HARD BEING LOVED BY JERKS

The freedom to be provocative

Daniel Leconte's 119-minute French language documentary is an energetic thriller of ideas. It covers a high-profile court case in which three Paris Muslim groups sued the left-leaning satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo for reprinting those notorious cartoon drawings from a Danish paper (Jyllans-Posten, September 2005) mocking Islam and Islamists. The French plaintiffs' particular focus was two images, most notably one with the Prophet wearing a bomb in his turban—and a new cartoon by Charlie Hebdo artist Cabu of Muhammad holding his head in chagrin and saying "It's hard being loved by jerks" ("C'est dur d'être aimé par des cons)" with the heading above "Muhammad overwhelmed by fundamentalists" (Mahomet débordé par les intégristes ").

A success at Cannes and part of the New York Film Festival, this verbose two-hour French documentary may be a hard sell for Americans but it's both significant and fun—it’s a celebration of French logic and a triumph of humor over solemnity. Seen primarily from the point of view of philosophical libertarians and the Charlie Hebdo team, it's a courtroom drama with livelihoods and freedom of expression at stake. Moreover, this case has an added importance because in other western countries where the cartoons were printed, the authorities declined to defend, while in the Arab world a number of journalists were fired for daring to reprint them. In the view of Charlie Hebdo's fiery but ironic leader Philippe Val, this was a victory for French Muslims.

Ironically "fundamentalist" in French is "intégriste," but one thing French fundamentalist Muslims seem not to want is to integrate. If laughter heals, Charlie Hebdo may have struck a blow for the cause of Muslim integration in France. Richard Malka, the defendants' energetic young attorney, made a dazzling shocker of a presentation toward the end when he said, in effect, "So you want to be treated like everyone else? Then here's what you'll get..." and he preceded to display a raft of earlier Charlie Hebdo cartoons of the most obscene, blasphemous, and scurrilous nature lambasting Christians, Jews, and even Buddhists over the past 10 or 15 years of the weekly—far worse stuff than the offending cartoons about Muslims. At first the court was aghast and Malka thought he'd blown it. Then everybody, including the judges and even the attorneys for the plaintiffs, began to break into fits of uproarious giggles--the fou rire the French are given to sometimes. After that, it was obvious who (the magazine) and what (freedom of expression) won the case. Malka's case is irrefutable, however uneasy one may feel about the way the Muslim fundamentalists were mocked and how that might be taken as part of a mythical "clash of civilizations." If they don't want to be mocked, the Muslims of France would not only be asking to be treated differently from everyone else but would be demanding a repressive society.

While Leconte's bias is extremely mild compared to, say, the obtrusive editorializing of Michael Moore, it's the nature of the case that not every viewpoint gets an equal hearing. The plaintiffs hardly tried—despite having President Jacques Chirac’s lawyer, Francis Szpiner, as their chief attorney: they only presented one witness, while the defense had over a dozen. Chirac was negotiating with the Saudis. He wanted to appease them. Sarkozy, not yet elected, sent a well-publicized fax the first day endorsing Charlie Hebdo. "I prefer an excess of caricature to an absence of caricature," he wrote." His opponent Ségolène Royale sent a more niggling text message of support.

It's pretty fair to say the fact that Charlie Hebdo won was a victory for free expression--and the right to be indifferently outrageous toward every religion--and agnostics and atheists too for that matter. But it's not exactly the case that every viewpoint gets an equal hearing. The film's two major weaknesses: not even the voices or texts of the actual trial could be shown, and the whole case gives little voice to Islamic moderates.

To make up for the lack of direct coverage, Leconte interviews the many defense "witnesses" to summarize their statements both during and after the trial. All the attorneys on both sides and one court representative also get ample opportunity to address the camera. So do many of the people in the hall outside the courtroom who conducted heated debates and made impassioned statements. Leconte also reports lively goings-on at the offices the paper being sued and L'Express, which also became involved.

Note that while in the US Muslims are about 2% of the population, Europe has 15-20 million, France the highest proportion, 7-10% of their total. Muslims are more visible and less scared in Europe than in the US--where the post 9/11 mood is frankly hostile and exclusionary. In France there are big movie stars who are Arabs; and an Arab woman, Rachida Dati, is Minister of Justice (one of seven women cabinet members appointed by Sarkozy). But a key issue outside this film's scope is whether Muslims, relatively new to Europe as a force, are secure and thick-skinned enough to endure normal criticism in a democratic society with a free press.