-

New York Film Festival 2007

Scroll down for reviews of the entire main slate or select from the titles indexed below.

Links to Reviews:

4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days (Christian Mungiu 2007

Actresses (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi 2007)

Alexandra (Aleksandr Sokurov 2007)

Axe in the Attic (Ed Pincus, Lucia Small 2007)

Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (Sidney Lumet 2007)

Calle Santa Fe (Carmen Castillo 2007)

Darjeeling Limited, The (Wes Anderson 2007)

Diving Bell and the Butterfly, The (Julian Schnabel 2007)

Fados (Carlos Saura 2007)

Flight of the Red Balloon, The (Hou Hsiao Hsien 2007)

Girl Cut in Two, The (Claude Chabrol 2007)

Go Go Tales (Abel Ferrara 2007)

I Just Didn't Do It (Masayuki Suo 2007)

I'm Not There (Todd Haynes 2007)

In the City of Silvia (Jose Luis Guerin 2007)

Last Mistress, The (Catherine Breillat 2007)

Man from London, The (Bela Tarr 2007)

Margot at the Wedding (Noah Baumbach 2007)

Married Life (Ira Sachs 2007)

Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Project (John Landis 2007)

No Country for Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen 2007)

Orphanage, The (Juan Antonio Bayona 2007)

Paranoid Park (Gus Van Sant 2007)

Pesepolis (Marjane Satrapi, Vincent Parannaud 2007)

Redacted (Brian De Palma 2007)

Romance of Astrea and Celadon, The (Eric Rohmer 2007)

Secret Sunshine (Lee Chang-Dong 2007)

Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas 2007)

Useless (Jia Zhang-ke 2007)

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-25-2014 at 09:59 PM.

-

Julien schnabel: The diving bell and the butterfly (2007)

JULIAN SCHNABEL: THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY

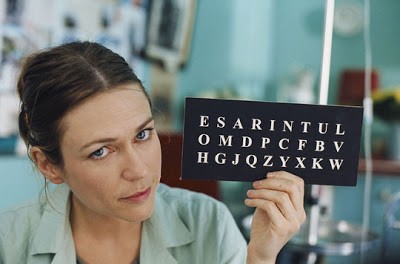

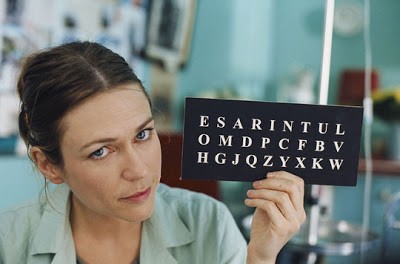

MARIE-JOSEE CROZE IN THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY

In the blink of an eye

Julian Schnabel’s brilliantly fractured acid-trip vision informs the best sequences of this film about Jean-Dominique Bauby, based on his eponymous book and veteran screenplay adaptor Ronald Haywood’s treatment. Bauby, “Jean-Do” to his friends and family, was at the top of his not inconsiderable game in his early forties, father of a cute boy and girl, lover, writer, and, most notably, editor of the fashion magazine Elle.

Then, Jean-Do woke up from a coma trapped in his body following a massive stroke, “locked in” by total paralysis. The English words are used by French doctors, and Schnabel wisely had Haywood’s screenplay translated into French and made the film in Bauby’s language and shot it where the events took place.

Maybe nothing later can match the empathy and shock of that first sequence, seen through a special "swing and tilt" lens (augmented by Schnabel’s own eyeglasses) refracting images in and out of focus and in and out of Jean-Do’s limited range of view, when he first comes out of his coma and the doctor tells him where he is and what has happened to him. He can see only what’s in front of him. Spielberg collaborator Janusz Kaminiski was the D.P.—one of many top-ranking collaborators: together with the other actors and Amalric’s voice (heard in his head: he can’t speak) to make this moment intensely, unsentimentally, almost beautifully real to us.

Finally Matthieu Amalric’s big bulging eyes are about to come into their own, except the doctors “occlude” (sew shut) one of them because it’s in danger of drying up. We see this from the protagonist’s P.O.V. as we see everything for a while. These early scenes are stunning, accomplished, and fresh. Remember when Schnabel showed a room as Basquiat saw it stoned? This is that, in spades.

Bauby, Harwood, Schnabel—and the Berck Maritime Hospital where Baugy was actually cared for: this is the fourth principal element behind the success of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. (The French title is Le Scaphandre et le papillon. ) Bauby’s real life caregivers appear in the picture and were consulted at every stage in the shooting at the hospital on how he looked and how he was cared for: the film balances wild invention with faithfulness to fact. The fifth element is a magnificent cast, with Amalric as Bauby, Emmanuelle Seigner, Anne Cobigny, Marie-Josee Croze, Patrick Cervais, Niels Arestrup, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Maria Hands, Max von Sydow (as Bauby’s father) and Schnabel’s wife Olatz Lopez Garmendia.

A speech therapist teaches the paralyzed Jean-Do to "speak" by blinking his eye to choose letters. He is despairing at first: his initial sentence is 'I want to die." But he has spunk, and he also has irony, anger, energy and will. And everybody around him is extraordinarily kind. We may have cause to remember that in the UN study Michael Moore cites in Sicko, the French medical system came out number one. But family and friends rally round and behave commendably too.

So the patient gains heart and decides to write a book, even though he must still use this slow, painstaking method that he learned with his speech therapist. He already has a contract for one, but he changes the subject to this overwhelming experience he is undergoing and all the thoughts and images that flow through him, which become a kind of poem about life and about his own life. His publisher finds an especially kind and patient collaborator. And she like the other women around him, is beautiful.

Jean-Do is trapped inside the diver’s bell (an image Schnabel and Amalric enact literally). But also he’s the butterfly because in memory and imagination he can flit anywhere, over mountain ranges, over decades.

A soundtrack uses Tom Waits, Singin' in the Rain, the 400 Blows theme, and other elements to pull together a wild flow of sequences with emotion and allusion. It’s a bit of a letdown to see Amalric sometimes, skillfully but still theatrically, impersonating the paralyzed Jean-Do directly onscreen. The film can be forgiven for occasionally failing to transform the ordinary and banal into the extraordinary because when it’s on point, it’s exhilarating to watch.

Bauby was a successful man, but his success and his life were of an ordinary kind. Writing a book one painfully chosen letter at a time was not ordinary, and he rose to the occasion in the thoughtfulness and originality of his text. This was not merely coping; it was transcending. It also gave Schnabel, coping with his mother’s death and his father’s fear of imminent demise when the project fell into his hands, a special opportunity to make a film that serves its subject faithfully and well, and at the same time is highly personal. The book became a bestseller. This film got Schnabel the Best Director award at Cannes this year.

This started off the press screenings of the New York Film Festival 2007.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 08:29 PM.

-

Masayuki suo: I just didh't do it (2007)

MASAYUKI SUO: I JUST DIDN'T DO IT (2007)

RYO KASE

A 'Kafkaesque' experience with the Japanese court system

Starring Ryo Kase, the Japanese soldier boy of Clint Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima, this could be seen as a “defense procedural.” A young man going on job interviews gets his suit jacket caught in the door of a crowded Tokyo subway car and a 15-year-old girl accuses him of groping her under her skirt. He’s stopped, arrested, and charged with lewd conduct. At times I Just Didn’t Do It has all the subtlety and life of a high school instructional film. But as a courtroom drama it uses its painstaking thoroughness to construct a clear-cut indictment of the Japanese court system. The consensus seems to be that the system is efficient and most of the accused actually are guilty (how do we know that?). But the few who are innocent have a snowball’s chance in hell of being exonerated. It’s convictions that are valued, and only three in a hundred who plead innocent escape conviction. The police in this case have thrown together their case hastily because they can. The film focuses on the accused and his lawyers’ efforts during a series of ten public court sessions to put together something that will challenge the system and lead to the young defendant’s being cleared. They haven’t much to go on. Months later they finally locate a woman who had told the police the young man wasn’t guilty, and was only pulling at his caught jacket. But her testimony, so eagerly sought by the defense, hasn’t much effect.

At first Teppei (Kase) sees a public defender who (disillusioned, we learn later, by having just lost a case), councils him to plead guilty, pay a fine, and get on with his life. The cops also warn him that a trial will be prolonged and destructive and its outcome very dubious indeed. But Teppei is innocent and outraged and will hear nothing of this. So his mother goes looking for lawyers to defend him.

The procedures do seem “Kafkaesque,” as the film’s promotional literature suggests. When, half way through, a sympathetic judge is suddenly and arbitrarily replaced by an obviously mean one, the deck is so obviously stacked against the defendant that it’s hard to keep watching. Tappei has just been released to his family at that point, but it means nothing—only that the prosecution is done getting evidence against him, including a small handful of pornography from his apartment. It’s hard to say at some points which is more manipulative, the Japanese court system as described here, or Suo’s film.

Detail does build up effectively, however. Each cog in the system, from cellmates to cops to ex-girlfriend to sleazy sex-crime courtroom groupie, is clearly delineated and given his or her appropriate moment. The suspense is contrived, but it still works. What are we supposed to think? Maybe what matters is the response of the Japanese public. Some of I Just Didn’t Do It is universal. We know through recent DNA exonerations that a lot of innocents have been sent to death row in the US. But at times the film seems so specifically Japanese that it is remote to westerners. Masayuki Suo is known in this country for his 1996 film, Shall We Dance.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 01:08 AM.

-

Carlos saura: Fados (2007)

CARLOS SAURA: FADOS (2007)

SINGER LILA DOWNS

Reflections through the scrim: a living tradition

Plangent yet brave, Portuguese "fados" songs are a tradition that goes back to the slums of nineteenth century Lisbon and is infused with African and Brazilian influences. This is another in the illustrious music and dance series the great Spanish director Carlos Saura has been producing sporadically for fifteen years, which includes the 1992 Sevillanas. the 1995 Flamenco and the 1998 Tango. Without voiceovers or spoken introductions, each of these lush cinematic experiences consists of a sequence of performances seamlessly linked by the use of wall-sized scrims, mirrors, enlarged projected images of performers or of landscapes (notably here the traditional skyline of Lisbon), shadows and silhouettes, not to mention simple unadorned closeups. Each presents a blend of singers, musicians, and dancers in large studios and sometimes on small stages. Each sequence is self-contained, but leads quickly on to the next. The blend of stylistic simplicity and visual and aural richness makes for a sensory treat every time.

That Fados is billed as "the ultimate encounter between folk and modern dance" and "the finest 'World Music' soundtrack to date" means several things. First, this tribute to fadistas past and present is an unusually eclectic range of styles from classics like Am�lia Rodrigues, seen only in a black and white film, to vibrant young talents like Mariza or Camani, to the major Brazilian singer-songwriter Caetano Veloso, to a hip-hop group. Each has a valid contribution to a tradition that is most clearly alive at the end in a "caf�" sequence where one after another young and old singers, male and female, stand up and contribute to a tightly continuous song. Second, unlike Flamenco and Tango, the fado doesn�t seem to involve a particular dancing style. Hence the dance is something added, and considsts mainly of modern interpretive styles choreographed by Patrick de Bana. One thing unique her and different from flamenco is the presence of harp, keyboard, mandolin and lute. As with Spanish music, the level of artistry with the plucked string is awesome and galvanizing.

The fado was defined first for Saura by Amalia Rodrigues, one of whose songs contains the lines, Love, jealousy / ash and fire / pain and sin. / All this exists / All this is sad. / All this is fado. Love-longing is an element; so is a nostalgia for home expressed in the unique word �saudade.� The fado has a distinct mood and sound, but it's not for me to try to define it. Suffice it to say that its rhythms are suffused with sadness, yet comforting, and that the mood is plaintive, yet determined; mournful, yet proud. It can take revolutionary politics as its subject as well as private experience. This film was an eye-opener for me; I thought the genre was a bit pass�. Obviously that is not at all true.

As with his earlier music and dance films Saura, who lists himself as the overall production designer, manages to start out with sequences that are powerful and irresistibly appealing, and yet move progressively toward more and more compelling performances. At the end this time the screen is filled with nothing but the eye of a big wooden camera. Looking into it seems to say: this is an inexhaustible tradition whose depths we have barely begun to plumb.

Shown among the press screenings of the New York Film Festival 2007, this is a sidebar item and not an official selection, but it's another jewel in the crown of Saura's musical and dance series and deserves to be seen, and seen again.

The cinemtography is by Eduardo Serra and Jose Luis Lopez Linares. The music is under the supervision of Carlos do Carmo, and the editing is by Julia Juaniz. All the work is impeccable.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 01:07 AM.

-

Eric rohmer: The romance of astrea and celadon

ERIC ROHMER: THE ROMANCE OF ASTREA AND CELADON (2007)

True romance? Perhaps. But transferring pastoral to screen may require more elaborate techniques than this.

Eighty-seven now, the indefatigable Eric Rohmer still explores his obsession with love, and especially young lovers. In this, his declared swan song, he follows the theme at one remove, via the pastoral romance of Honoré d'Urfé, penned in seventeenth-century France and set in the Forez plain in fifth-century Gaul. This is a classic star-crossed lovers tale with a happy ending that involves some cross-dressing by the pretty Celadon (Andy Gillet). He thinks his girlfriend Astrea (Stephanie Crayencour) has forbidden him to come into her sight, so he poses as the daughter of a high-born Druid priest. Though too tall, as cross-dressers often are, the striking Gillet is certainly beautiful enough to pose as a girl (Crayencour, though appealing, can hardly compete for looks—till she bares a breast, one area where Andy is out of the running). When Celadon, as a "she," gets so friendly with Astrea they start kissing passionately early one morning in front of some other girls, there's enough titillating gender-bending going on to give this otherwise odd and dry piece a closing shot of contemporary interest.

As opening texts explain, the film was made in another region because the Forez plain is "urbanized" and otherwise ruined today. The mostly young cast wears costumes designed to evoke the seventeenth-century conception of what d'Urfe's antique (and largely mythical) shepherds and priests wore. Just as Rohmer's contemporary young lovers in his Moral Tales have little to distract them (or us) from their flirtations and love-debates, d'Urfé's characters are those of an ancient pastoral tradition who never get their hands dirty and spend their time engaged in quiet, paintable pursuits like dancing, singing, or frolicking in the grass discussing the ideals of courtly love. Rohmer uses this idealized world as a more detached version of his usual emotional landscape. However, this film is, to its detriment, closer to the artificial and somehow un-Rohmer-esquire late efforts The Lady and the Duke and Triple Agent than to his most charming and characteristic work.

In the beginning of the story, the lovers have apparently had a spat. Celadon allows Astrea to see him dancing and flirting with another girl at an al fresco dance. Later he insists it was only a "pretense," but Astrea jumps to the conclusion her boyfriend is a philanderer and is so angry she banishes him forever from her sight. His reaction is to throw himself into the river. While Astrea and her girlfriends go looking, he's washed up on shore at some distance, nearly drowned. He's rescued and nurtured back to waking health by an upper-class nymph (Veronique Reymond) who lives in a (presumably seventeenth-century) castle.

A druid priest (Serge Renko) and his niece Leonide (Cecile Cassel) supervise Celadon after he flees from the nymph's clutches. He pouts in a kind of pastoral tepee for a while, and then is persuaded to put on women's clothes so he can be close to his beloved. One wonders if Rohmer hadn't lost control of the casting when we see the over-acting, annoying Rodolphe Pauly as Hylas, a troubadour who opposes the prevailing platonic tradition in favor of free love with multiple partners. Pauly completely breaks the heightened, elegant tone and introduces an amateurish note, which is the more dangerous since the simplicity of the outdoor shooting already risks evoking some French YouTube skit. Things liven up considerably when Celadon is in drag, but by that time Rohmer will have lost the sympathy of many viewers.

Adapting seventeenth-century pastoral tales to the screen may be a far-fetched enterprise at best, but there must be better ways of attempting it than this. Paradoxically, though the pastoral ideal is about purity and simplicity, recapturing it is likely to require more elaborate methods. The Sofia Coppola of Marie Antoinette, with its gorgeous, eye-candy mise-en-scene, might have managed it—and that film does have a pastoral interlude, though not "pure" pastoral but aristocrats camping it up as shepherds and shepherdesses. Rohmer's pleasing but essentially bare-bones style worked well for most of his career because his people and their conversations were interesting enough in themselves; the intensity of his own interest made them so. Such methods don't work so well here. The talk in The Romance of Astrea an id Celadon is too stilted and dry most of the way to hold much interest. For dyed-in-the-wool Rohmer fans, of course, this mature work is nonetheless required viewing. Newcomers as usual had best go back to My Night at Maude's and Claire's Knee to understand the perennial interest of this quintessentially French filmmaker.

Seen at the press screening for the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center in September 2007.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 01:06 AM.

-

Sidney lumet: Before the devil knows you're dead (2007)

SIDNEY LUMET: BEFORE THE DEVIL KNOWS YOU'RE DEAD (2007)

PHILIP SEYMOUR HOFFMAN, ETHAN HAWKE

Like a train wreck

This movie directed by the 83-year-old Lumet brings to mind Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs. Depending on how you look at it, Tarantino is the master, or the infamous originator, of the scrambled time-line. That film begins after a disastrous failed jewelry store robbery and follows, with overlapping chronologies, the subsequent behavior of various participants who wind up in a warehouse. The title of this new botched jewelry store heist picture comes from an Irish toast: May you be in heaven half an hour before the devil knows you're dead. According to Lumet at the NYFF press screening, the screenplay came in over the transom from one Kelly Masterson. Lumet wasn't sure, at the Q&A, if Masterson was a man or a woman, so they don't seem to be close. Lumet did the rewriting. This included making the primary characters behind the robbery not just friends but brothers. This is an important touch, since this is, or became, a story of total family meltdown—one whose intensity and fatality is such that links with Greek tragedy have been mentioned.

Things are not going very well for either older brother Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman) or baby brother Hank (Ethan Hawke). Andy is embezzling his company to pay for his expensive drug habit. Things aren't clicking between him and his wife Gina (Marisa Tomei)—and unbeknownst to him she's sleeping with Hank. Hank, who's not doing well financially and is behind in his child-support, is a lovable loser—which makes you wonder why Andy should talk him into carrying out a robbery. He seems incapable of so much as delivering a pizza. What Andy doesn't own up to at first is that the place to be robbed is their own parents' "mom and pop" strip mall jewelry store. Hank knows he can't do a robbery himself. He secretly enlists a seedy character he knows named Bobby (Brian F. O'Byrne) to enter the store while he waits in a rental car.

Bobby's a tough guy all right, but hey, none of these boys is the sharpest knife in the drawer, and Bobby makes a hash of it, and in the process of getting himself killed shoots Hank and Andy's own mother (Rosemary Harris), who just happens to be minding the shop that day because an employee couldn't make it.

Reservoir Dogs skips the actual robbery scene. It's reconstructed in subsequent dialogue. Masterson/Lumet's screenplay includes the scene of the robbery, then goes back and forth over the four days prior to it and the week following it in chronologically scrambled segments. These are a problem. Lumet had to add labels giving date and point of view for these out-of-sequence segments, because he himself couldn't follow where they were meant to fit on the first reading. What you can't tell on viewing the film is why these sequences need to be so scrambled other than to conceal, for a while anyway, how dumb this robbery scheme is. What they clearly show is what a lot of trouble the brothers are in, before they make things much worse.

Lumet knew this plot-based movie would need great acting to put across the characters and screw the emotions up to a fever itch. He began with Philip Seymour Hoffman, who was given choice of which brother to play. Hawke was called in: and he gives a surprisingly strong performance as a weak man. Albert Finney as Charles, the father, naturally maintains the intensity level. And Tomei fits. The cops aren't helpful, so Charles decides to find out on his own who staged this robbery, and he seems to know where to look. Bobby had a kid, and the brother of the kid's mother, Dex (Michael Shannon), who's no more fun to be with than Bobby, comes looking for Hank, and finds him.

Before the Devil excels in its powerful evocation of total meltdown. It reads as something that goes too slow at first, than rushes too much at the end. Lumet, who's astonishingly vigorous at 83 and is said to work incredibly fast still, calls this story "melodrama," and thus defines it as working by certain rules, among them the suspension of disbelief where a lot of stuff happens with shocking speed. Arguably too much happens and though by intention not everything is explained about how the characters end up, the ending provides not the catharsis of Greek tragedy but the sensation of having witnessed a train wreck. The element of Tarantino that you most miss is the good dialogue. But you also miss the well placed dramatic pause.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 01:06 AM.

-

Claude chabrol: The girl cut in two (2007

CLAUDE CHABROL: THE GIRL CUT IN TWO (2007)

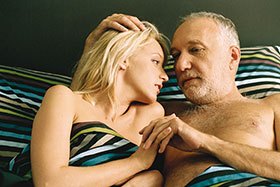

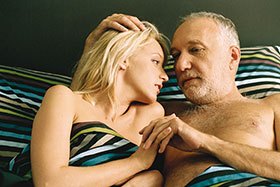

FRANCOIS BERLEAND, LUDIVINE SAGNIER

How happy I would be with either. . .

Chabrol's latest film (La Fille coupee en deux) is a barbed comedy set in the city of Lyons. A charming young TV weather person, Gabrielle Deneige (Ludivine Sagnier), suddenly finds two men competing for her affections. The successful writer Charles Saint-Denis (Francois Berleand) is appearing on TV when he first runs into Gabrielle; her mother (Marie Bunel) works at the bookstore where he's later signing his new book. Though he's a good thirty years her senior, they feel an instant connection. To her, he's sexy, fascinating, and rich. But not nearly so rich as Paul Gaudens (Benoit Magimel), the capricious young heir to a vast local pharmaceutical fortune. With his tinted Napoleonic hairdo and flamboyant wardrobe, Magimel spins onto each scene like some spoiled princeling. He's amusing, absurd, and a bit menacing. There are obvious hints that he may be completely wacko. He spots Gabrielle too at the book signing, falls for her, and woos her aggressively henceforth. Saint-Denis lives with professed contentment and serenity in a splendid superbly brittle ultramodern house in the country and has a vivacious and understanding and longstanding wife, Dona (Valeria Cavalli). Gaudens lives in a mansion with his widowed mother (Caroline Sihot) and two grown sisters. Both men have some dark scandals and improprieties hidden in their past, though we don't learn much about them. In this relatively provincial world they are well acquainted with, and have always cordially detested, each other.

It appears that Gabrielle is led into some indecencies by Charles, whose special club and in-town pied-a-terre she visits more than once. Preposterous as it may seem, Paul, who's head-over-heels for Gabrielle, appoints himself Gabrielle's moral savior. Though she's sought after by Canal+ and her current boss wants to make her the emcee of a new show, Gabrielle eschews these opportunities for advancement and instead devotes nearly all her time to pursuing or being pursued by these two men, enjoying the attentions of the curiously endearing Paul, but running off the instant the sophisticated Charles summons her—because he's the one she truly adores. (In the French cinema, older men are quite commonly seen as the more attractive.) Both Berleand, a convincing ladies man, and the visually transformed Magimel, by now a Chabrol regular if not a male muse, are splendid in their roles. Sagnier, whom Americans will probably best remember as Tinker Belle or the naughty young woman in Ozon's Swimming Pool, projects a world of beauty, charm, vivacity, and (relative) innocence.

The Girl Cut in Two is highly amusing. The script by Chabrol's longtime assistant Cecile Maistre sparkles with witty zingers in every scene and has particular fun with the literary world, "intellectual" TV shows, and as always with the director, the gilded squalor of the upper bourgeoisie. This being Lyons, one of France's chief gastronomic capitals, there are lots of good restaurants and there's lots of good wine; many coupes of good champagne are tossed back. Nifty sports cars are driven—and when Paul arrives anywhere in his, he leaves it at the door, and tosses away the ticket afterwards with a disdain any driver would envy. For a good part of the time, each scene is more fun than the last.

The dialogue is smooth and glib, but it's also smart. This isn't a murder mystery, though a pistol does appear and later it is used. It's more a portrait of emotional conflict. And it treats issues of high and low; of love trumping ambition and then turning out to be naïve; about wealth and madness; about men and women; youth and age. At the center of it is Gabrielle's "search for love." But in focusing on Paul and Charles, Gabrielle is, of course, carrying out that search in two quite wrong places. Both men are as deeply tempting as they are flawed, so it's no wonder she wavers hopelessly between them.

Gabrielle marries Paul, but only on the rebound from Charles. This leads to unhappiness, discontent, and finally violence. The film has transposed to contemporary times (without loss of credibility) the story of the 1906 murder, in New York, of the famous American architect and womanizer Stanford White (represented here by the writer) by the husband of his latest mistress. It's a theme dealt with before, notably in Richard Fleischer's 1955 Girl in the Red Velvet Swing and Milos Forman's 1981 screen adaption of E.L. Doctorow's novel, Ragtime. But the Maistre-Chabrol treatment is unique.

The Girl Cut in Two is one of Chabrol's lightest and brightest and most buoyant films. It may not, as few can, rest on the top shelf with his absolute classics, but it is the best thing he's done in years.

The film was shown at the press screenings of the New York Film Festival 2007 in September; it opened in France in early August.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 01:04 AM.

-

Ira sachs: Married life (2007)

IRA SACHS: MARRIED LIFE (2007)

PIERCE BROSNAN, RACHEL MCADAMS

Marriage woes of a solemn fool

Ira Sachs' Forty Shades of Blue was a story about a young Russian émigré woman and her American music impresario husband who isn't really there for her—it's a movie that's rambling, freshly observed, carefully planted in its southern milieu, and verité in style. For his new feature he was granted the opportunity to work in the Hollywood system with name actors, and he chose to shift gears completely. He's adapted an old "genre" novel (his word) by John Bingham, who was John Le Carré's mentor in MI5 and the model for Le Carre's iconic character, George Smiley. Married Life is a glossy period story with ironic twists. It's set in the early Fifties. Partly a social comedy, partly a tongue-in-cheek thriller, partly a perverse love story, it weaves a bit too much among all these possibilities to leave a lasting impression.

Harry Allen (Chris Cooper) wants to run off with a young blonde and thinks he must kill his wife to spare her the pain of divorce. That's a new kind of mercy killing, a droll motive for murder. Whether it's a good pretext for a meditation on relationships and love, as the director believes, is another question. A greater awareness of the period might have led to the observation that divorce itself, at that time a somewhat scandalous social institution, was more disturbing than the mere psychological loss of a loved one.

Sachs is a gay man approaching straight marriage through the filter of a penchant for Joan Crawford and Bette Davis movies, much as Todd Hughes approached a Fifties interracial affair and a married man's homosexuality through the filter of Douglas Sirk melodramas in his Far from Heaven—which, like this movie, featured Patricia Clarkson as the wife. Married Life is more restrained than the style-obsessed Far from Heaven. But though it annoys less, it does not impress as much.

With its world of stifling bourgeois "poshlost" and its bumbling, trapped killer, this film is reminiscent of some of the minor novels of Vladimir Nabokov, and that would be a good thing, if only Sachs were Nabokov. But he isn't. Sach's protagonist, Harry Allen, is a solemn fool. He goes about planning his murder, unaware that introducing his friend Richard Langley (a pleasant, but somewhat stilted, Pierce Brosnan) to his new girlfriend Kay (Rachel McAdams), a young widow, is a very risky move, given that she's an out-and-out babe and Richard is appealing, available, and drives a nice convertible. Anyone with an emotional IQ of 100 would see Richard has more charm than the dour Harry; but Harry's level is well below average, even for the disdainful 21st century conception of the American Fifties. Harry's also seriously mistaken about his wife Pat (Ms. Clarkson, in a dark red wig)—she has other quite appetizing possibilities he isn't in the least aware of.

The movie advances at a measured pace with all its period accoutrements tidily in place. Everyone has dyed hair and Chris Cooper's apparent proclivity for very dark suits is much in evidence. An atmosphere of great restraint is created, the better to stun us with the story's bombshells.

While in Far from Heaven the emotions were ramped up and operatic, those of Married Life cause barely a ripple. People say they love each other, but we don't feel it and there's no visible chemistry between the actors. There is some limited compensation in the dry comedy of certain lines of dialogue. There is stylized, if wan, amusement in the repetition of an idea, "a person like you can't build happiness on the suffering of others, not with the burden of morality you carry," spoken unwittingly by several characters. But that's not exactly an epigram. True, there's something unique about the confection Sachs has so carefully whipped up. But while this is more coherent than Hayne's Fifties melodrama, it utterly lacks its impact. According to Sachs, Five Roundabouts to Heaven, Bingham's source novel, ends with a lot of people dying. That might have been nice. Couples deciding to stay together after all? Gee, this is quite the year for Family Values. Married Life ends with a solemnity so completely worthy of its humorless hero one may wonder if one's earlier giggles had been unintended.

An official selection of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, fall 2007.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 08:42 PM.

-

Carlos reygadas: Silent light (2007)

CARLOS REYGADAS: SILENT LIGHT (2007)

Beautiful desperation

This third work by the Mexican auteur signals a concern with process right away in a slow opening six-minute shot of stars and clouds in a dark sky. The camera slowly inches forward, shrubbery slides away, the sky brightens along the horizon and turns red, and dawn breaks. The only sound--but it's a powerful one--is the hum and twitter of nature and the mooing of cows, a susurration whose volume modulates as the images do. It's a lovely sequence, smooth and sure and beautiful, but it demands your patience, and it is deliberately ineloquent, and so is the rest of the film, which focuses on a family in a Mennonite community living in Mexico, who speak to each other in Plaut Deutsch, an archaic language. Reygadas assembled most of his cast from this community. They don't eschew engines, like the Pennsylvania Amish. They drive cars and trucks and use modern farm equipment. But their clothes and their ways are simple. The women wear cotton frocks and tie their heads up in little scarves. Their houses are plain and clean and old-fashioned. When trouble comes, there's no external static to hide it.

Reygadas is excellent at working with non-actors. They may share the film's prevailing reserve, but they seem ineluctably real. The children help with this. Whether they're praying or eating or swimming, they're just themselves. Jakob is a dairy farmer. He's having an affair with another woman, and it's tearing him up. His wife knows about it; so does his best friend; and he tells his father in a later scene. He and his wife have half a dozen young children. Their children are bright little things, and they get alone fine; but Jakob believes, and tells others, that the new woman is better for him; that if he had met her originally, he would have chosen her over his wife. Yet he tries to end it. And his girlfriend says after a lovemaking scene that this must be the last time between them. The two women and Jakob are all three suffering. Even in the first scene in Jakob's house, after breakfast is over and his wife and children go out, he sits at the kitchen table and weeps. His wife is quiet and gentle, but she isn't happy any more.

There are some surprises down the line. Silent Light (Stellet licht)is an homage to Dreyer's Ordet, and becomes closer and closer to that film toward the end. There are several particularly memorable scenes--a visit to Jakob's friend's garage where he drives around in circles and sings a Spanish song in his truck; a terrible misadventure by a roadside in heavy rain; a wake. Throughout the editing and images and pace have the same sureness of that opening sequence of sky and dawn. There is a similar, shorter shot of the same horizon that, with a satisfying cyclical effect, ends things. Ultimately this is in its way a very beautiful film. Its protagonist is faced with a moral dilemma in a very pure form because his life itself is pure. His father says his involvement is the work of the Devil. But here is the dilemma: Jakob thinks it may not be at all. He doesn't know what to do. His girlfriend says she is suffering, but at the same time adds that she has never been so happy in her life. There are no distractions from this story, no subplots, no complications. That is the beauty of it, and its purity of focus. The images and compositions, especially the exteriors and landscapes of Silent Light, are exquisite. These are very different people, quite well protected, it would seem, from the distractions and demoralization and social decay of Bruno Dumont's rural France, and the world of Silent Light is very much cleaner and more beautiful than Dumont's, but in its elemental ineloquence this film has some similarities to the French director's, partly perhaps just because both filmmakers work with non-actors and in their own way, at their own pace: both are sui generis.

Silent Light is about people in crisis, but it doesn't exude desperation like Reygadas' two previous films or share their impulse to provoke. It's as if the director found a kind of peace in this special anachronistic community. And perhaps a degree of spirituality. But whether the ending is to be taken in a supernatural or mechanistic sense is left unspecified. Still not for the mainstream, this does show Reygadas reaching out tentatively toward a wider community. Here is a protagonist who's part of an organized, upright world, the father of a family, with a common problem--not a misfit, a desperado, a lowlife, an outlaw, but a kind of everyman.

Shown as an official selection of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center 2007.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-25-2014 at 09:46 PM.

-

Abel ferrara: Go go tales (2007)

ABEL FERRARA: GO GO TALES (2007)

More fun to talk about?

Here is a movie that Ferrara calls his "first intentional comedy." Its protagonist, Ray Ruby (Willem Dafoe), runs a joint where girls with other ambitions strip and dance around on a stage and lap-dance for a sparse crowd of men. He has a couple manager-bouncers, including Bob Hoskins. The shrill, dirty-mouthed landlady (Sylvia Miles) comes and sits at the bar blaspheming and demanding four months back rent and threatening to bring the marshals. The girls are constantly demanding to be paid. ONe of them is Asia Argento. Another one comes and declares that she's pregnant and Ray tries to talk her into continuing to perform. There's an Irish bookkeeper who has a file showing where all Ray's lotto tickets are stashed. He and Ray watch the drawing for an $18 million prize and they've got the winner—only they can't locate it. Then Ray's brother Johnny (Matthew Modine), a highly successful hairdresser, who bankrolls the joint, appears and announces he's going to pull the plug. Some young doctors come in who saved one of the guys with the Heimlich Maneuver, and they enjoy the girls—till one of them discovers his wife on the stage dirty dancing, and there's quite a fracas.

That's about it, really. This sounds like a stage play. It nearly all takes place indoors either in the club or Ray's office. However, it's not a play because it was shot at Cinecitta in Rome, where they built the set. a club with its own lighting that, as Abel Ferrara tells it, never had to close. And the shooting, which in part is a homage to Cassavetes' Killing of a Chinese Bookie, was done with a couple of DV cameras—with their capacity to go on and on and on shooting a scene—as well as some surveillance cameras to add in the occasional Super 8 effect—and with a very clear-cut screenplay but a great deal of leeway for improvisation. The cameramen were not at all neglectful of the nearly naked girls, whose work is constantly in evidence whenever the cameras are rolling in the club. All of which is unlike any play you're likely to see. The movement, the level of improvisation, the complexity of the set, are movie stuff. And the cast too is a movie cast, even if these actors all have good stage experience, notably Dafoe, who was present every day of the shoot and managed that as his character manages the club.

These are chaotic and grim and desperate circumstances, but they're handled with a sense of the absurd throughout: hence the "intentional comedy." Modine comes in with a pod of swept-forward, bleached hair and carrying a little dog. There's also a cabaret sequence when some of the girls perform their "art": one plays classical on an electric piano, a guy does a totally garbled recitation of Antony's funeral oration from Julius Caesar; another does a peculiar "magic" show; and so on. And Sylvia Miles' over-the-top shrillness sets a tone of ridiculous excess. Some of Dafoe's improvisations have an amusing sense of grasping desperation about them—especially when he confronts the suddenly pregnant dancer and even when he defends his club as if it were as important as life itself. Melodrama is replaced by intentional bathos.

Still, as was plain at the New York Film Festival press screening when Ferrara, Dafoe, Miles, and several others talked to FSLC director Richard Pena and answered questions from the audience, this is a movie that's probably more fun to talk about than to watch. Not in a New York Film Festival since King of New York, which started a great row at the time, Ferrara is a character whose biography is best read in his films and his explanations together. For Go Go Tales, his parents are John Cassavetes and Robert Altman, but there's something uniquely disreputable and hilarious about his version of their styles.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 02:41 PM.

-

Brian de palma: Redacted (2007)

BRIAN DE PALMA: REDACTED (2007)

Scattershot

De Palma’s new picture about the rape and murder of a young Iraqi girl and slaughter of her family by American soldiers—based on a known incident—is a passionate screed. It’s a collage of modern media showing what we do and don’t see at home and thereby it seeks to frame this atrocity in a fuller context. First of all you get amateur videos by Salie Angel Salazar (Izzy Diaz), of the Marine squad in question. Salie didn’t get into film school, he tells us, and now he hopes this video journal will get him in when he gets out. If he lives. Then you get an overblown French documentary (Barrage) about a checkpoint, with ultra-closeups, ponderous editing, and elegant baroque background music. (If this is a parody it’s inappropriate; if it’s a homage, it’s poorly executed.) The checkpoint is the one manned by Salie’s squad. Later you get on the ground interviews and coverage by invented Arabic and American news media. Here and there you get more mechanical coverage (because literally filmed by machine): shots from a military surveillance camera; a piped-in line from a hidden Jihadi night vision camera connected to a website called “Shuhada’ ul-hurriyya” (Martyrs of Freedom); and hidden cameras used by the American authorities to record interviews of the men after their crime. Along the way you also get video blogs by a masked whistleblower and another by a disturbed relative back home in the USA.

The effect of all these electronic sources is a kind of surfeit of verite modes. Sure, something like this is how we learned how Abu Ghraib looked (but only after the information was leaked and Seymour Hirsch wrote about it). And this is certainly one way of showing there are people who know stuff the mainstream media don’t come close to telling us. (Of course we know that, though, and we know about the event this film is based on, from the New York Times.) However, some of the behavior and incidents as De Palma shoots them aren’t believable. Some of the Iraqis don’t look like Iraqis. (It seems part of the film was shot in Jordan. Obviously it wasn’t shot in Iraq.) Salie’s crude filmmaking gives De Palma license also to be crude. But the one thing that may be needed here is a coherent narrative. Instead, we get some bad and unconvincing acting and some overly pointed lines. Unlike Jarhead, for instance, which was based on a soldier’s firsthand (prose) account of Gulf War I, there’s not much effort to convey down time or non-combat interests of the men. This is image overkill, not wisdom.

The unit is part of Alfa Company, stationed at Camp Carolina, Samara—or Mahmoudia, south of Baghdad. Soon you will see Master Sergeant Jim Sweet (Ty Jones), an experienced man, on his third tour, blown up by just the kind of hidden explosive device he’s warning the others about. His sudden departure is to be lamented for more than one reason, because Sweet’s is the wisest voice—but also because Jones is possibly the best actor of the lot. When Salie initially opens his camera, you meet Rush (Daniel Stewart Sherman) and the arrogant, cold-blooded Reno Flake (Patrick Carroll). Flake is new, and when he wastes a young pregnant woman at the checkpoint, he says it’s as easy as picking off fish. Rush and Flake are later going to instigate the unauthorized raid on the house where the fifteen-year-old girl they want to rape lives with her family. Flake is the key figure, the spark that sets off the explosion of evil, and Flake and Rush are the rottenest apples in the barrel. This doesn’t mean Flake’s a convincing or well-drawn portrait. It’s more logical and worthwhile to say soldiers become hardened during their tours (and then later, sometimes, fed up with what they’ve done, horrified). This movie gives us the good guys and the bad guys right away, and there aren’t any gray areas, or changes of character. Rather than showing us that good people in wartime can do bad things, De Palma shows us that mean nasty bad low-life people do bad things, which they were always destined to do, only needing a slight pretext (Sweet’s death; being horny). The notable non-badies, aside from Sweet, are stereotypes: the bookish type Gabe Blix (Kel O'Neill), who by a strange coincidence is reading John O'Hara’s Appointment at Samara, and the conscience-ridden Lawyer McCoy (Rob Devaney). Maybe Flake isn’t any more convincing than McCoy as a character, but at least he’s more colorful. If Salie comes across as an audacious naif, McCoy comes across as a wimp. When the rape is about to happen, he leaves the house to keep "guard." He objects, so he refuses to watch. All these actors, except for Ty Jones, seem as green and unready for film work as their characters are inadequately trained to conduct themselves properly in a difficult combat situation.

After this incident, one of the squad is kidnapped and beheaded in revenge and here’s yet another kind of modern video: an Islamic terrorist snuff film, which we get to watch. We’ve also gotten to hear, and partly see, the rape, because Salie has hidden a camera in his helmet for the event. When they first break into the house, suddenly an American TV newsperson appears in there with them. And Rush talks friendly to her. Somehow, that seems unlikely. De Palma’s desire to work multi-media into everything is out of control. This film, which is overtly cobbled together, not surprisingly feels that way. A short sequence of stills of collateral damage victims at the end seems one more tacked-on thing. It’s too short, or too long—those who followed the war have seen plenty of such images, and those who haven’t, would need to see many more than this to make up for the mainstream American media’s avoidance of them.

De Palma made another movie about the abuse of a young woman in wartime—a much better one. His Casualties of War (1989) was filmed almost two decades after the events it describes from the Vietnam War. As with Paul Haggis' currently showing In the Valley of Elah, which more subtly and indirectly deals with Iraq, it seems filmmakers are stepping in too soon for their post-mortems and analyses this time. Haggis’ film comes out better, though. He uses "found footage" too, but very sparingly and to correspondingly much greater effect. There is a sense of slow revelation that makes Valley of Elah, however downbeat and doctrinaire, dramatically compelling in ways that Redacted never is for a minute. A comparison of Redacted with Haggis’s current film and De Palma’s earlier one about Vietnam reinforces the feeling that traditional drama may still be a better way to bring home issues about wartime misconduct on film than this kind of multi-feed pseudo-documentary. Redacted is anything but "redacted" (cut, censored, edited): it feels smeared out all over the screen. Hence the title is a misnomer. With the excess, the effect is unfortunately numbing. I kept looking for mistakes—and I found them—and that doesn’t happen in a good drama, even when you know a lot of it's made up.

This is a valiant effort by Mr. De Palma, who besides Hitchkockian genre flicks and shockers has a history of serious engaged filmmaking as well. But it’s destined to be watched in the wrong way by the wrong people, and has nothing new or satisfying to offer for audiences sympathetic to De Palma’s point of view.

Seen at the press screenings of the New York Film Festival, Lincoln Center, 2007.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 06:30 PM.

-

Hou hsiau hsien

HOU HSIAO HSIEN: FLIGHT OF THE RED BALLOON

SONG FANG, SIMON ITEANU

The Zen of the quotidian, in Paris

Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao Hsien just made a film in Japan, Café Lumiere. This, his first foray out of Asia to make a film, was commissioned by the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. It's a precise study of the quotidian, and since that quotidian is in Paris, it’s particularly graceful and lovely, despite the themes of urban loneliness and stress, which seem to grow seamlessly out of the last film into this one. It’s about a frazzled lady named Suzanne (Juliette Binoche) with over-bleached, unruly hair. Her life is a little like her coiffure—she can’t quite seem to control it. She has a seven-year-old boy named Simon (Simon Iteanu), with a fine profile and a big mop of hair, and an annoying downstairs lodger (Hipolyte Girardot), a friend of her absent boyfriend, who, it emerges, hasn’t paid his rent in a year. Suzanne’s work is unusual. She puts on Chinese puppet plays, for which she does all the voices. As the film begins, she picks up Song (Song Fang), a Taiwanese girl studying filmmaking, fluent in French, who is going to be a "child minder" for Simon. And then she picks up Simon at school, introduces them, and takes them to the apartment.

The Musee d’Orsay lent Hou a copy of Albert Lamorisse's 1956 classic 34-minute short The Red Balloon. This is a kind of homage to and riff on it. There’s a big red balloon that keeps following Simon. Song also starts shooting a little film of Simon with a red balloon.

Hou admits he didn’t know a lot about Paris. Somehow he got hold of a copy of Adam Gopnik’s book about the city, Paris to the Moon, an enlightening and truly smart study of the French and their capital that grew out of the years when Gopnik was The New Yorker’s correspondent there—when he also had young a little boy along. From Gopnik Hou learned about how old Parisian cafes still have pinball machines (flippers, the French call them). He also learned that the merry-go-round in the Jardin du Luxembourg has little rings the children catch on sticks as they ride around (like knights in the days of jousting). Hou put both those things in his movie. He says that once he had Simon’s school and Suzanne’s apartment, the film was safely under way. He provided a very detailed scenario (penned by Hou with co-writer and producer François Margolin) complete with full back stories, but the actors had to decide what to say in each of their scenes. They did, quite convincingly.

Hou’s life has been full of puppets from childhood, and he made a film about a puppet master. This time he incorporates a classic Chinese puppet story about a very determined hero: he meant it to describe Suzanne, who creates a new version of it. He also brings in a visiting Chinese puppet master. Suzanne calls in Song to act as interpreter for the puppet master during his visit, and also asks her to transfer some old family films to disk. The lines between filmmaker and story, actors and their characters, blur at times.

Flight may be seen as a contrast of moods. That tenant downstairs has become a real annoyance. Simon’s father has been away as a writer in residence at a Montreal university for longer than he planned. These two things are enough to make Suzanne fly off the handle whenever she comes home. But Song and Simon are calm souls, and they hit it off from the start. With Simon, all is going well. He’s happy with his young life. Math, spelling, flipper, wandering Paris with Song, catching the rings at the Jardin du Luxembourg, taking his piano lessons: the world according to Simon is full and good. Suzanne hugs Simon as if to draw comfort from his love and his serenity.

Hou has a wonderfully light touch. Changes of scene feel exactly right. The red balloon and the occasional judiciously placed pale yellow filter by Hou’s DP Mark Lee Ping Bing make the Parisian interiors seem almost Chinese, and beautiful in their cozy clutter. Let's not forget that red is the luckiest color in Chinee culture.

You could say that nothing really happens in Hou’s red balloon story. Like other auteur-artist filmmakers, he requires patience of his audience. But nothing in particular has to happen, because he stages his scenes with such grace and specificity that it’s a pleasure to watch them unfold; a lesson in life lived for its zen here-and-now-ness. Occasionally perhaps here the absence of emotional conflicts or suspense leads to momentary longeurs, but one’s still left feeling satisfied. Clever Hou, who is clearly a master of seizing the moment, can make you feel as much at home in Paris as any French director. Though Flight of the Red Balloon may generate little excitement, it provides continual aesthetic pleasure, and at the same time has the feel of daily life in every scene. This is a method that can incorporate anything, so at the end the Musee d’Orsay is easily worked in, through Simon’s class coming for a visit and looking at a painting by Félix Vallotton—of a landscape with a red balloon. It’s in the nature of good film acting that Binoche’s character, though sketched in only with a few brief scenes, seems quite three-dimensional. This is Hou at his most accessible, but there is more solidity to this film than might at first appear.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 06:32 PM.

-

Cristian mungiu: 4 months, 3 weeks and 2 days

CRISTIAN MUNGIU: 4 MONTHS, 3 WEEKS AND 2 DAYS (2007)

ANAMARIA MARINACA

A fine modulation of grays

It’s not exactly clear to me why this film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year. Mungiu has exercised tight control over his material. His actors are impeccable. His visual style is appropriate to the theme. His subject is compelling and his focus on it is unflinching. But still. There is something missing here, some flair, some life, even. Some people think the Coens’ No Country for Old Men ought to have won the Palm. We’ll see about that.

Abortion was banned in Romania in 1966. Those who got abortions and those who gave them risked imprisonment. The story is set in the late Eighties, in the last days of the Ceaucescu regime. As in the East Germany of The Lives of Others, we find that to outsiders the last days of communism seem far grimmer than we might have realized. Otilia (Anamaria Marinca) and Gabita (Laura Vasiliu) are university roommates. Otilia helps Gabita get an abortion. The man who performs it is ironically named Bebe (Vlad Ivanov).

4 months was shot by Oleg Mutu, the cameraman for the remarkable Cristi Puiu film, The Death of Mr. Lazarescu. He uses no dollies or cranes, tripod or Steadicam for this. The film is developed in a prevailing dull, even blue-gray. During interior scenes, there is very little camera movement. All this is to convey the mood of limitation, constraint, hopelessness. Otilia is the firm one. Gabita is nervous and sensitive. She is weak; she has put this off too long; and her fears cause her to lie. She makes the hotel reservation on the phone, instead of in person (the hotel, obviously, is in the same town). She lies to Bebe and says Otilia is her sister, because she is afraid to go and meet him but sends Otilia to do it instead. She lies and tells Bebe she’s two months pregnant, though she knows it’s much longer.

Bebe is a very mean man. But Ivanov is a remarkable actor in his way (Mongiu built the film around him), and there is nothing simplistic about his evil. In fact, he turns rather nice at the end of the process, wishing Gabita well and offering to come back later that day or tomorrow, if needed. But that is after he has exacted a toll of humiliation and menace.

The whole process of the abortion is excruciating, not because of any physical horrors or gore, though there is a little gore, but because the film drives home the uncertainty and danger of it all, and draws things out to the maximum. You don’t know what’s going to happen.

A dictatorship is terrifying but as Nabokov delighted in showing in some of his novels such as Invitation to a Beheading, it is also a papier mache charade with the muse of comedy grinning secretly around every dark and greasy corner.

What is seriously absurd in 4 months is that at a time when Gabita may be in mortal danger in a soulless hotel room, Otilia goes off for several hours to have dinner with her boyfriend and for the first time meet all his family, an experience she seems to find as tedious and excruciating as we do.

4 months is at its best is in the details, which convey better than the story the gray grimness of life in communist Romania. That’s what Mungiu wants to convey. The endless search for a pack of Kents. The black marketers down the hall. The miserable local cars. The ill-lighted streets. The hotel room clerks that turn having a reservation into a suspicious condition. There are other communist Romanias, other Romanian experiences in brighter colors. But maybe that is what the jury at Cannes wanted too, though, nd felt compelled to reward—the gray version. And Mungiu’s symphony of grays is impeccably modulated and consistent. I don’t completely buy it. But there is a mastery of craft here.

Seen at the press screenings of the New York Film Festival, Lincoln Center, 2007. No Country for Old Men is to be screened in one week.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 06:35 PM.

-

Ed pincus, lucia small: The axe in the attic (2007)

ED PINCUS, LUCIA SMALL: THE AXE IN THE ATTIC (2007)

They wanted to do something

The Axe in the Attic, a film about Katrina survivors, signals the return to action of a documentary guru who had his beginnings in the Sixties, Ed Pincus, teamed up with a new practitioner with some good work already to her credit, Lucia Small. Its special interest is in the way it openly shows the filmmakers' emotional involvement—especially Small's—in their subject. They make a real point of showing how they wavor between examining the disaster with journalistic detachment and actually pitching in to help—if only by handing out a few dollars, which Small more than once is moved to do.

But this makes you wonder: what is this film finally about? It was fine, even essential and fascinating, for Nathaniel Kahn to talk about himself in the course of his documentary about the great Louis Kahn, (My Architect)—because he was Kahn’s own unacknowledged son and was seeking to find out what his father was really like. But what do these two white people from Boston have to do with the poor and mostly black people’s post-hurricane experiences? Are they talking about those people, or about white liberal guilt?

One saving grace of the film is that Pincus and Small do cover a wide range of places and people, "from a close-knit African American family that comes from the Lower Ninth in New Orleans to start over in the wintry hills of suburban Pittsburgh, to a single, white working mother raising two teenagers living in a condo on the outskirts of Cincinnati, to Baker, Louisiana, where the residents of FEMA’s largest trailer park ('Renaissance Village,' with almost 600 trailers) live as if in a refugee camp." The two filmmakers, whose words those are, touch down in those places, and also in Kentucky, Alabama, New Orleans, other parts of Louisiana, and Texas—and they keep track of the people they talked to in each place and do some final quick follow-ups.

Nonetheless it’s hard not to see Lucia Small’s behavior as displayed at times as anything but complaining, and to wonder why certain included scenes didn’t end up on the cutting-room floor. Is it necessary to see her in the driver’s seat saying how tired and demoralized she is when they’ve just arrived in New Orleans and gotten lost, downtown? Even some of the displaced people seem representative more of their own dysfunctionalities than of the specific effects of the disaster.

It’s fine to focus on personal experience, on the constant tears and sometimes curses of flood and hurricane victims who've lost all they had. The experiences of Pincus and Small, their squabbles and doubt, however, pale by comparison.

Pincus and Small do make a good working team. On their “sixty-day road trip” he is the cameraman (most of the time: she films him a few times), and she’s up in front with the microphone, using her sensitivities to get people to open up. Which they do. There are some stories that could give you nightmares, as they do their tellers. Dead bodies of babies floating in the water. People stranded on their rooftops for days (the "axe in the attic" was to get up there, kept by those who’d been in floods before). The smell of death everywhere in the convention center where everyone is helpless and trapped for days. A child later poisoned by formaldehyde. A man walking two and a half hours each way from the FEMA trailer camp to and from work, because he hasn’t the money to take the bus.

This does not, however, provide the big picture or consider the relevant political issues. Those have even been to some extent covered by mainstream media, or more revealingly dealt with by alternative sources such as Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now; but they're needed for context here. In a way, a couple of people in an SUV with filmmaking equipment can give an interesting personal picture. But when it’s devastation on the post-Katrina scale, a larger picture is needed, and it takes enormous dedication, Herculean energy, to do the subject justice: in those terms, The Axe in the Attic just doesn’t quite cut it. It’s not competition for Spike Lee’s mini-series When the Levees Broke. Since the majority of the poor people "hardest hit" by Katrina and least recovered since are black, it makes a real difference that Spike Lee, besides having superior resources, is a black man.

The Axe in the Attic begins with Small’s videos of TV coverage of Katrina. She just felt so concerned, she pointed her video camera at the television screen. There’s an appealing pathos in that. She wants so much to do something, and that’s how she started. But this signifies the piggyback quality of the whole effort. Documentaries have not been one of the New York Film Festival’s stronger areas, and this is no exception.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-08-2014 at 06:49 PM.

-

Wes anderson: The darjeeling limiited (2007)

WES ANDERSON: THE DARJEELING LIMITED (2007)

JASON SCHWARTZMAN, OWEN WILSON, ADRIEN BRODY

Saying yes to everything, or trying to anyway

The first thing to note about Wes Anderson’s new film (featuring Owen Wilson, Jason Schwartzman, and Adrien Brody, as the Whitman brothers, Francis, Jack, and Peter respectively) is that it was shot in India, mostly on a colorful old train traveling across Rajasthan. The train perhaps replaces the elaborate constructed set of the ship Anderson used in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. That ship was a bit of an albatross. The movie cost $60 million to make and is Anderson’s least admired work. The train is part of a faster and cheaper production and it’s crucially different: it’s a real train, in motion during the shoot. It’s still perhaps an arbitrary and whimsical set—and has the kind of bright pastel colors Anderson likes—but this time, as Brody has said about the shoot, they were learning to "live in the moment," just letting things happen, and using whatever they observed of Indian life as elements in the film. Every time they turned around there was something unfamiliar, remarkable and new to see; if they could, they worked it in. This isn’t navel-gazing (though there’s that) but also discovery and wonderment. It’s partly a homage to Anderson’s fascination with India and admiration for Jean Renoir’s The River and the films of Satyajit Ray. The soundtrack isn’t just sweet Seventies rock but music from Ray’s classics.

Every Anderson film is about families (and his crew and casts are like family); this one is mostly, of course, about sibling relationships. Wes wrote the screenplay together with Roman Coppola and Jason Schwartzman, who're both cousins, and old friends of his—and hence like brothers, paralleling the film’s three. They also went to India and took a trip before the writing, living the experience before they made it into a screenplay.

Darjeeling’s trio of obviously privileged sons have been estranged for a year, since their father’s death—which their mother, Patricia (Angelica Houston), now in a convent near the Himalayas, chose not even to attend. (There’s a flashback of the brothers en route to the funeral, with Barbet Schroeder as a German mechanic.) Francis, the eldest, has summoned Jack and Peter to this Indian train voyage as a way of bonding, and at the same time seeking spiritual enlightenment.

But before we get to that, there’s a kind of pendant, called Hotel Chevalier, which sometimes will be shown with Darjeeling, sometimes not. It’s a ten-minute film with Jason Schwartzman and Nathalie Portman. And it’s a perfect little film in its way. Schwartzman is already Jack, though the film was completed a year earlier. He’s enjoying solitary luxury in a nice Paris hotel, when his girlfriend (Portman), also estranged, turns up. Jack, who likes to go barefoot and wear expensive suits, is a writer, and this sequence comes up in Darjeeling as a short story he’s working on. Hotel Chevalier is a bridge into the full-length film, and was also a way for Schwartzman to readjust to working with Anderson as an actor after the long interlude since Rushmore.

Everyone is damaged. We know how actually damaged Owen Wilson is from the news of his recent suicide attempt; and Anderson’s comedies are perennially tinged with melancholy and dysfunction. Francis (Wilson) arrives with his head all bandaged up from a terrible motorcycle accident. Peter (Brody—the only Anderson newcomer among the principals) is running away from the pregnancy of a wife he regrets marrying. Jack is pining for the girlfriend of Hotel Chevalier, who has apparently slept around. She can’t commit to him and he can’t give her up. The brothers stop at temples and see sights and shop—for Indian medicines to get high on; poisonous snakes; pepper spray. The men are bossed around by the train’s chief steward (Waris Ahluwalia), and Jack has a quick affair with a stewardess, Rita (Amara Karan), whom the others know as the sweet lime girl. Francis, who bosses his other brothers around, also has a secretary and planner, Brendan (Wally Worodarsky) who prints up and laminates little copies of their itinerary, which changes from day to day, and has such tasks as keeping track of the brother’s extensive array of custom Marc Jacobs Vuitton luggage, which belonged to their father, and finding adapter plugs. Brendan eventually defects, but Francis hopes to lure him back.

The brothers effect a rescue of some boys in a capsized raft near a waterfall; but the boy Peter tries to rescue doesn’t survive, and they all go to the funeral. They weren’t going to go and see their mother, but they do; Huston gives an especially strong performance. A ceremony to celebrate their bond and spiritual union goes wrong, but later they do it again. And this time it works. The movie begins with Bill Murray (Steve Zissou in Anderson’s last outing) who runs after the train and misses it. The throwing away of the baggage is perhaps a little too obvious a symbol. Maybe the rescue episode feels contrived and emotionally detached.

Either you like Wes Anderson or you don’t, no doubt. But if you share my impression that he’s one of the most important American filmmakers of his generation, his new film is obviously essential viewing. It looks like this time has gone better than the last, even if Nathan Lee is right in saying it’s more "a companion piece to Tenenbaums than a step in new directions." It will be nice if a lot of people get to see it proceeded by Hotel Chevalier (which, anyway, will be on the DVD). The New York Film Festival 2007 has chosen The Darjeeling Limited for their opening night film. Anderson’s later films are all elaborate twittering machines. It’s interesting that this time the machine has such a strong element of chance, that it happens, and is found, rather than is constructed: there is a new direction, which is to just let things be, or, as Francis says in dictating the course of their journey, to "say yes to everything." Or try to, anyway.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-25-2014 at 09:47 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks