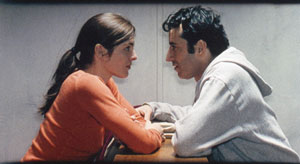

As much as I've tried to make a case for the logic behind the film's more puzzling elements, after one viewing I am not fully persuaded that

Colossal Youth's many fragments cohere into a masterful whole. According to Peranson, Costa spent two years shooting 320 hours of footage, and no doubt he established strong relationships with his actor-subjects in that time, but that still does not discern whether the film's seemingly loose structure is a vivid reflection of the dissolute lives playing out on screen, or is simply dissolute, indulgent filmmaking. Yet I have no reservations in lauding the film for the specific and innovative approaches it takes toward depicting a way of life that is usually portrayed, when it is portrayed at all, without attentiveness or empathy. It is in the attempt to create a house of cinema from the derelict moments of these people on screen that I find

Colossal Youth pulsing with purpose.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks