-

Satoshi Kon: Paprika (2006)

SATOSHI KON: PAPRIKA (2006)

Chaos is come again--but we saw it in 1989

Most film buffs old enough to have survived the Eighties developed at least a passing interest in Japan animé during those years and there were moments when I was temporarily seduced by it. That was when it seemed new and daring and inexhaustible, and there were combinations of folk legend, gross sexual excess, and cuteness that certainly made you forget about Walt Disney. Though it’s not strictly speaking animé at all, for my money it’s Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: the Iron Man (1989: “A man is experiencing problems with metal showing up and protruding from his body…he must face the antagonist which lives inside him as he continues to sprout more and more metal”) that blows all the rest away for sheer nightmare strangeness and visual invention. Maybe the Film Society of Lincoln Cernter festival jurors were not the best people to choose animé for us; maybe they were seduced by the cinematically referential elements of Paprika. It may be above average for the genre but it is not destined to be one of the great ones.

The premise is that a gadget called DC-Mini that allows psychiatrists to enter their patients’ dreams has gone astray and mayhem ensues. In an energetic opening sequence, police detective Konakawa (Akio Ohtsuka) escapes a whirlwind of chase scenarios out of film noir, Tarzan movies, etc. glimpsed through an elevator door. With him is a young red-haired woman named Paprika (Megumi Hayashibara). This self-referential intro refers to filmmaking and film fandom repeatedly, another aspect that may have appealed to the festival pundits.

The main one is the way the plot circles around a dream machine. Isn't that Hollywood? The opening sequence turns out to be a dream, and Dr. Atsuko Chiba, who is also Paprika, announces that somebody has stolen the DC-Mini and is using it to turn the team of shrinks she's associated with into zombies spouting nonsense. This brings in colorful character No. 1, a monstrous overeater and the genius inventor of the dream device named Tokita (Toru Furuya). Can he figure out how to get DC-Mini back?

We go in and out of dreams and reality – sounds like Michel Gondry; but it turns out to be a lot more synthetic. The English word “terrorist” pops up, perhaps inevitably, because this story concerns saving the world from chaos and also protecting the natural universe from the invasion of the mechanical that is so horrifyingly and far more unforgettably portrayed in Tetsuya: The Iron Man.

The rest is mostly a chase, with a special feature being that Atsuko and her Paprika clone become heroines and so the film departs from the misogyny too often found in the genre—except for one lapse when a male character “undoes” a female one in a quite shocking way.

Paprika is not extraordinary visually. After all the taboos and physical impossibilities the genre has already long explored, that would be hard. In scenes where masses of toys come to life, they do take on a “new” look – a sort of glazed-over surface reminiscent of old children’s book illustrations. It’s quite an attractive effect, but not an especially innovative one. Mass backgrounds full of chaotic movement are occasionally strikingly handled; production values are above average. Otherwise, the cute women, the Tracy-jawed detective, and cuddly nerds that populate the plot are depicted in quite conventional fashion. Akira and Mayasaki still wear their laurels intact. Ultimately it’s for its premise rather than its style or its narrative invention that Paprika has been chosen as part of the New York Film Festival’s selective 2006 list.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-29-2011 at 10:20 PM.

-

Nikolaus Geyrhalter: Our Daily Bread (2005)

NIKOLAUS GEYRHALTER: OUR DAILY BREAD (2005)

Artistic documentary: does it work?

Nikolaus Geyrhalter's Our Daily Bread is more like a conceptual art piece than the usual documentary film. It consists of 92 minutes of filmed images of European food industry workers, most of them doing their jobs, and some of them having their lunches. There are no verbal guidelines provided; there is no identification of the industry or the location, no statistics or other information about the work being done. This includes chickens, cows, pigs, cattle, and fish, everything from breeding to slaughtering, as well as workers spraying crops, picking fruit and vegetables, and so on. The 35 mm. hi def images are handsome, bright, and clear, with excellent color. In a neutral sort of way, you could say they are "pretty." The result is a kind of numbing, disturbing visual wallpaper. Geyrhalter has produced an artifact as cold and as inhuman as the processes he has filmed. That's why this reads like a conceptual piece that might be shown in the room of a museum as part of an exhibition, rather than in a movie theater.

All these images are from large scale production. There are no small farmers represented. When an animal is killed, the chances are hundreds of them are being killed. Baby chicks are shunted around on conveyor belts, into boxes, sorted by hand, and sent into other conveyor belts, like inanimate objects. Cattle and pigs are shunted along in mechanical conveyors to slaughter and taken apart afterwards with machinery, while workers also repeat monotonous gestures. It isn't made clear whether it is the actions or their scale that are to be noted, and presumably objected to. (Is it bad to raise animals for food? Or at least much more wrong to do that on a huge industrial scale?) There is an obvious irony in the contrast between the worker's little sandwiches consumed staring into space and the vast quantities of future edibles they contribute to the preparation of. But actually the images here are at the raw end of food preparation. There is no cooking, canning, or bottling. And Our Daily Bread doesn't show the baking of bread, either on a small level or a large one.

An Amsterdam Film Festival award jury described these scenes in its citation as "a powerful cinematic experience! A series of shocking and indelible images...unremittingly merciless and nightmarish....A vision of Hell. Not the Hell of our theologians but one constructed by our politics, our markets and our food technologies. This is a great and important film and we are delighted to honor it with the Special Jury Award."

Yes, this is a remarkable film, exhaustive and exhausting in its methods and effect and appropriate for inclusion in a film festival where work that pushes the envelope is going to be sought out. The New York Film Festival's emphasis on high artistic merit and originality justifies the inclusion of Our Daily Bread as one of its 28 official selections. However, one may wonder if a "documentary" that reads more as an art piece than as instruction can really be effective as polemic or information. And yet it would appear that polemic and information are Geyrhalter's interests here.

It's true that some documentaries "work" brilliantly without voice-over commentaries. The French To Be and to Have, which describes a year in the life of a rural schoolteacher, is deeply affecting without a word of interjected commentary. But when we are in the world of public social issues, or matters for concern and debate, it is more usual for the filmmaker to inject words into the debate. Examples of that kind of documentary are Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11 or the more recent global warming film featuring Al Gore, An Inconvenient Truth. Our Daily Bread doesn't contain a word of commentary. And for the English-language viewer, none of the occasional lunchtime workers' conversations is translated.

Consequently it seems that this kind of film is unlikely to reach a wide audience. But isn't reaching and influencing a wide audience just what this kind of committed filmmaking is about? In situations like this, Geyrhalter is right in saying that it may not matter whether the food factory is in Austria, Spain, or Poland, "or how many pigs are processed every year in the big slaughterhouse that's shown."

Except that it does matter. Because it is the scale that makes the world of industrial food production and high-tech farming inhuman and inhumane and disturbing. Do you want to become a vegetarian? What we see done to plants isn't very pretty either. All these events and actions take on a different cast if seen within a small scale, done for local use.

There is no objection to the images Geyrhalter has assembled. They deserve to be seen and thought about. They are important. And this relentless presentation of them, without words and without commentary or verbal information, does leave an impression. But an example of a better treatment of this kind of subject matter for the general public is Deborah Koons Garcia's 2005 The Future of Food, which focuses on genetic manipulation and cloning and the patenting of plants and has a regular voice-over narration to tell us about the subject, as well as interviews with people whose lives have been effected by Monsanto's and other corporations' intervention in farming. Geyrhalter says that he and his crew did interviews, but they found that they detracted from the overall effect. We must ask what kind of effect he was trying to create, and whether documentary filmmaking shouldn't be focused more on informing us than on simply "affecting" us. It is important to be "affected," but we also need to know what is going on, why it is going on, and what we might do about it, other than feel depressed and numbed.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-24-2010 at 07:20 PM.

-

Emmanuel Bourdieu: Poison Friends (2006)

EMMANUEL BOURDIEU: POISON FRIENDS (2006)

Malik Zidi in Les amitiés maléfiques

Youthful indiscretion, adult failure

[W A R N I N G : S P O I L E R S]

If I'm right that Alain-Fournier's Le Grand Meaulnes (The Wanderer) is still pivotal in French culture, the slightly disreputable bad-boy mentor remains an essential part of the myth of youth over there. And you'll enjoy Emmanuel Bourdieu's fast-paced, light, but biting study of a role model who crashed, so long as you accept the film's very French, Parisian, focus on getting ahead early in a small, competitive, celebrity-conscious, idea-smitten intellectual world. That's the world the good-looking Alexandre Pariente (Alexandre Steiger) enters when he walks into the Sorbonne literature class of famous writer-scholar Professor Mortier (Jacques Bonnaffé), straight off the train and carrying his suitcase. Alexandre and new arrivals Eloi Duhaut (Malik Zidi) and Edouard Franchon (Thomas Blanchard) are instantly impressed by André Mourney (Thibault Vinçon), who has the audacity to address this first class, speaking with enormous confidence (and some elegance) about the subject of writing.

Alexandre, Eloi, and Edouard become André Mourney's disciples. His theme is always that people only write because they are too weak to resist, and that they must have a good excuse for giving way to that weakness. André is really a terrible boor and ultimately disreputable: but he has more panache than the others, as that opening class showed. He turns out to be destructive, and a liar. A terrible liar. He steals the girl they all want, the librarian Marguerite (Natacha Régnier of Ozon's Criminel Lovers/Les amants criminels and Fontaine's How I Killed My Father/Comment j'ai tué mon père), telling Eloi to burn his love-note to her (because, of course, one should never write love-notes) and then moving in on her himself. He has a good effect on Alexandre, telling him he should really be an actor. That turns out to be true, and Alexandre has immediate success in the French classics. But André's pompous negativism leads Eloi to go out in the middle of the night and dump a novel he's written in the trash. Eloi's mother is a well-known, slightly crazy writer, Florence Duhaut (Dominique Blanc), so Eloi's understandably diffident. But André's influence on him is destructive.

It turns out that André is a protégé of Professor Mortier. But André's so busy pontificating among his peers, he neglects to work on his thesis. He tells Eloi to work on James Ellroy, and suggests there's a scholarship at Berkeley waiting for them both. When things go bad between Mortier and André, the latter leaves, pretending that he is going to an American university. This is the crucial moment when the others, who've been held together one way or another by André (even those among them André has been most abusive to), finally have to grow up and become independent. We already know by now what a rotter André has been. We've seen him open the beautiful Marguerite's laptop and delete a short story she has written. (Eloi finally replaces André in Marguerite's good graces by retrieving it).

Eloi is faced with a problem when he learns his mother has also retrieved his discarded novel, submitted it to her publisher faking his signature, and had it accepted. Eventually he allows it to be published, and it's a great success. He doesn't like his original title though. The new one is: Les Amitiés maléfiques (Poison Friends).

The young actors are all appealing. Malik Zidi will be remembered from Les Temps qui changent, Water Drops on Burning Rocks, and Place Vendome-- and will soon be seen in none other than Le Grand Meaulnes (a new version). The least known till now is Thibault Vinçon (André), whom the director spotted and admired for his "technical brilliance and sensitivity" at an acting workshop. Vinçon reappears at the end, and the way he conveys André's rapid transformation from rising star to instantly old raté (failure) is brilliant.

Bourdieu knows whereof he speaks: he is himself the son of a well known French intellectual and film figure. This is a smart and thought-provoking film whose classic theme doesn't prevent if from being fresh. A sterling choice on the part of the Film Society jury.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-19-2017 at 12:25 AM.

-

Zacharias Kunuk, Norman Cohn: The Journals of Knud Rasmussen (2006)

ZACHARIAS KUNUK, NORMAN COHN: THE JOURNALS OF KNUD RASMUSSEN (2006)

Off-putting but deeply significant storytelling

Kunuk's 2001 Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, which won the Camera d'Or award at Cannes and was the first feature film ever made in the Inuit language, was a dramatization of a thousand-year-old tale of the nomadic seal-hunting clans of Alaska that tells of a vendetta and a purging of evil; it had the flavor of an ancient Scandinavian epic and was hauntingly harsh, remote, and violent but had fleeting elements of humor and an unmistakable sensuality. This new film is drawn from the same region and stars the same pool of actors from the local population but concerns events in the early 1920's described in Rasmussen's travel documents. He was a Dane with Inuit blood who spoke the language. He was a kind of anthropologist-adventurer. The journal of his fifth Thule Expedition across the Canadian Arctic recounts the information he gathered during a brief but uniquely significant encounter.

Rasmussen came with a trader, Peter Freuchen, and an anthropologist, Therkel Mathiassen. At this moment in 1922-23 he found a people in transition. The Inuit were being converted to Christianity, but were still at a stage when among some of their members the two ways still existed. His information is crucial, and of lively interest to modern-day Inuits, because once the Inuit were persuaded to cast out their spirits and give up shamanism their Christian leaders immediately forbade them even to speak of the old ways, declaring them to be the work of Satan. Rasmussen found men who still spoke of the old ways and sang the old songs. Kunuk and his close collaborator and cameraman Norman Cohn have brought this lore back to life. Like an ancient legend, this film (strictly speaking video, shot in HD 24P) like its predecessor preserves the record of a culture.

Cohn and Kunuk have worked together on a number of short videos for years. They and elder Pauloosie Quilitalik and the late Paul Apak developed a style of "relived" cultural drama, "combining the authenticity of modern video with the ancient art of Inuit storytelling." Both features are best understood as interfaces of events and their retelling.

As the film begins, the great shaman, Avva (Pakak Innuksuk)and his family are living on the land some distance from Iglulik, his home community, which has taken up the teachings of Christian missionaries. Rasumssen comes with Freuchen and Mathiassen. They hear and record the life stories of Avva and his wife Orulu. Their son Natar impulsively agrees to guide Freuchen and Mathiassen north to Iglulik. In the last part of the film Avva and his clan make a terribly difficult journey toward home, facing strong headwinds and conditions that almost starve them. Ultimately Avva will abandon his ancient spirits, and they will wander off, wailing, as the evil spirits wandered off at the end of Atanarjuat. But along the way, individuals will be important, notably Avva's strong-minded daughter Apak (Leah Angutimarik), who still has sex with her dead husband and will have nothing to do with her new one.

The essence of Kunuk-Cohn's collaboration is that their projects come out of and go back to their indigenous sources. It makes little sense to talk about how 'authentic' the film is. The actors are playing their grandparents. The target audience is the small community of Iglulik from which these films and the cast have come. There is no competition. Kunuk was an artist with a little education who sold sculptures in Montreal in the early Eighties to buy a camera. He was going to take still pictures. Instead he went into video. There was no television or video where he came from. He brought it back. His aim was to film his father. He still seeks to preserve the culture of his people. Norman Cohn was a widely exhibited video artist who has worked with Kunuk since the Nineties and now is closely associated with Iglulik and divides his time between there and Montreal. This film is a Danish co-feature with Danish actors playing the explorer-visitors' roles.

In the early scene where Avva introduces his family members to the Danes I felt like a visitor, lost in a strange language. That is how both Kunuk's features feel. It takes at least half an hour to acclimate oneself and begin to fall into the rhythm of different ways. It's also true that this film is less exciting than the previous one in narrative terms. It lacks quite the level of physical action. It is primarily a story about storytelling, about receiving information. But it also has moments of plangent grief and shock as Christians appear and men give up their spirits, give up the culture of 4,000 years, as Cohn described it in an interview, to follow "Ten Commandments," as if to imply those Ten could hardly replace a whole culture rich in survival strategies. Young people, he and Kunuk say, are again at a transitional stage. They have given up Christian practice and are welcoming back the old ideas and ways.

Anyway, whether you find the storytelling technique of these films compelling or simply off-putting, they are unique cinematic documents of the endangered culture of a people who have lived successfully for millennia in the harshest conditions on earth. It would be hard to justify not including this film as one of the New York Film Festival's selective list for 2006.

[NOTE: Kunuk and Cohn have established a website for Inuit and indigenous filmmaking with free video downloads: http://www.isuma.tv]

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-26-2021 at 01:04 PM.

-

Warren Beatty: Reds (1981)

WARREN BEATTY: REDS (1981)

A maverick magnum opus with a political theme -- rare in American movies

Warren Beatty's magnum opus Reds was presented as a revival film official selection of the New York Film Festival 2006 to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of its original appearance.

Reds's greatest virtue may be that it's grand, without being pompous, filmmaking. It's a film that takes some pride in being big and turbulent and unruly. It's important, but it's not tidy. It's in part certainly very much about ideology, but it avoids sharp, well-honed edges or large hard-etched "points."

John Reed (played by the film’s impresario, its sole producer, director, co-author, and star, Warren Beatty) was a man who happened to be able to write a first-hand account of the Bolshevik revolution, a long-time bestseller called Ten Days That Shook the World. At that time early in the twentieth century in America Reed arguably was a central figure, if only in the sense that during his time in Greenwich Village he managed to be (as he wanted to be) consistently at the center of things American political and cultural – when he wasn’t in Russia (which was pretty central then too). Roger Ebert thinks the movie "never succeeds in convincing us that the feuds between the American socialist parties were much more than personality conflict and ego-bruisings" (that may depend on how hard we need to be convinced to begin with), but we do care about Reds (Ebert thinks) as “a traditional Hollywood romantic epic, a love story written on the canvas of history, as they used to say in the ads…it is the thinking man’s Doctor Zhivago, told from the other side, of course.” What about the choice of Warren Beatty and Diane Keaton as the lovers? Initially that may seem an odd and chemistry-poor decision. (I'm not sure I overcome that impression.) But arguably the film takes sufficient time developing each of its main characters to make them into rounded people, complex enough to be attractive to others and to each other. Beatty uses the romance to hold the story together, and in doing so, he follows a conventional enough scheme. Reds stands out from other American mainstream products – and for all its maverick central force, it remains that – in its attempt to deal seriously with complex socio-political events during a turbulent period, and to approach them in an open-minded way. Beatty weaves other significant characters into the fabric of his drama, notably the leftist activist Emma Goldman (Maureen Stapleton, who got the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress) and the radical editor Max Eastman (Edward Herrmann), who are members of the same political-intellectual salon into which he brings Louise, as is the playwright Eugene O'Neill (Jack Nicholson).

Beatty’s filmic recreation of John Reed is good in not being too serious or too idealized: in having a silly side Beatty's Reed perhaps has something of himself. Reed's lover Louise Bryant (Keaton), though originally a bourgeois lady from Portland, is similarly rounded; she's led by her relationship to Reed to develop other facets and strengths, and further enlarged as a personality the way the film depicts her long affair with the alcoholic O’Neill, played by a toned-down but emotionally potent Nicholson. His discontent and negative energy are disturbing. Personalities anchor the film; but in some of the political debates and adventures one loses track and forgets why Reed is somewhere in Russia. He is at the center of things. But why he is where he is otherwise at certain moments is uncertain. In its ambition to keep juggling the many balls of major personalities and major political currents and historical events, Reds loses some of its narrative clarity and momentum over time. Complex political and historical currents are tracked, but the emotional trajectory loses its momentum. Nonetheless the film develops sweep in its length of three and a quarter hours. One walks out convinced that the material was complex enough to be worthy of such length, even if Beatty and his co-writer Trevor Griffiths could not whip it all into shape.

Whether it’s all worth it on the stage of international cinema or not, this is a film of historical interest as a great independent project, begun logically in the Seventies, but completed right in the middle of Hollywood by an American intelligent and engaged enough to be star, director, writer, and producer, to raise $35 million to do it, and to make more or less the movie he wanted to make – right in the middle, so to speak, of a wave of conservatism and yuppiedom, in the early Eighties, when people were thinking about making money and making it, when Ronald Reagon was President of the United States. What more appropriate time to reexamine this achievement than in the middle of the second term of George Bush II? No doubt Beatty took on this story because he was interested in a time in America when it was rife with left-wing politics. But he is realistic, and he made a Hollywood movie, with big stars and romance. And that’s what it is and remains. But one can’t imagine anybody else making it, and that’s what makes it worth revisiting. Warren Beatty is an admirable maverick in the clone-heavy world of Southern California media-moguldom. He’s a real person. And this is his great performance as a person and as an artist. I first saw it with a group of real communists. “We’re “reds,” they said as we walked out. The theater staff looked impressed. I was bowled over by their pride. Not everyone watches this film as a “traditional Hollywood romantic epic.” It would never been made if that were all it was. Its grandeur and ambition are still moving and it must not be forgotten. For a more pungent treatment of a political and social theme starring Beatty, consider Hal Ashby's 1975 Shampoo.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:24 AM.

-

Pedro Almodóvar: Volver (2006)

PEDRO ALMODÓVAR: VOLVER (2006)

A return, forward

It doesn’t take an Almodóvarista to see that the Spanish director is in top form in this new one, a "return" (the basic meaning of the many-leveled title) to his home region of La Mancha (and the "social rites of my village with regard to death and the dead"); to the past, to "maternity" and the mother, to the artist’s youth; to working with women (and to two of the best women has worked with in the past, who shine enormously here: Penélope Cruz and Carmen Maura (both splendid, as is everyone); and to comedy. Though the signature style isn’t as campy and exotic as at other times, the feel is lively, fluid, and consistently fun.

Almodóvar has spoken of how restless he has always been, and says that in the making of this film he has felt a new serenity; he has put something back together that was out of place – his past, perhaps, and his old discomfort with the conservatism and machismo of his place of origin. "I believe that with Volver I have recovered part of my 'patience,'" he writes. Now that he is past fifty, he is willing to look back; but he says that the new projects on his desk concern the future. He looked back once. Maybe that was enough!

In Volver, we begin with the dead. In the first scene women are cleaning the graves of their family, and someone talks of a woman who took care of her own tombstone all her life. The dead are never gone. That is the way of the village. The villagers are in constant touch with the dead. But if they’re not at rest, they may have to return. The villagers believe in spirits. Almodóvar says he has never accepted death or understood it, but that he’s starting to get the idea that it exists.

No director is more distinctive than Almodóvar, and yet he has made a great variety of films, exploring all different sorts of situations and characters. This "return" is not a reworking of past themes. If you want to know what’s new in Volver in a nutshell, you might consider it Italian neorealism blended with a murder thriller à la Chabrol. It’s also been described by the filmmaker as a combination of Mildred Pierce and Arsenic and Old Lace. There is a corpse to dispose of, with consequences that are both comic and chilling. There is a working class setting in which Penélope Cruz’s Raimunda reigns, a gorgeous queen bee, tough yet sensitive, with “cleavage for days” as Julia Roberts described her look in Erin Brockovich. Penelope’s look and dress are conscious references to Sophia Loren, and the film includes a clip of Visconti’s Bellissima with Anna Magnani. These idealized "housewives" or film Super Moms are imbedded in the village world Almodóvar creates here. But needless to say, the intricate plot line into which these two elements of soulful lady and Chabrolesque murder story are blended into a brightly-hued Almodóvar "naturalism" is unique to this director.

Raimunda (Cruz) is married to an unemployed laborer. She has a teenage daughter (Yohana Cobo). There is Sole (Lola Dueñas), her sister, who makes a living as a hairdresser. Their mother Abuela Irene (Carmen Maura) died in a fire along with her husband. She appears first to her sister, the aging Aunt Paula (Chus Lampreave) and then to Sole, but she most needs to resolve matters with Raimunda, and a village neighbor, Agustina (Blanca Portillo). Augustina is looking after Paula. Her mother mysteriously disappeared on the day of the fire. There are horrors and taboos to be dealt with, but the failure to connect seems to be the most important wrong that’s righted in this drama.

Though there’s a party and a song – Raimunda sings the song "Volver" – and someone returns from the dead, Volver is less high concept and frenetic than recent films by the Spaniard: no transsexuals, no love story or stories within stories, and for that matter only tiny roles for men. Regular musical collaborator Alberto Iglesias' score provides a buoyant accompaniment to the editing with several Bernard Hermann and Douglas Sirk moments. The visual look is more subdued than usual but the interiors and exteriors both do rich justice to the La Mancha setting and some shots are beautified with yellow filters. The movie's simplicity otherwise corresponds with its serenity and its return to rural roots. Penélope Cruz is magnificent here; and Carmen Maura is as warm and appealing as ever. It’s as a vision of living as filled with warmth and simplicity that this latest Almodóvar work most appeals, despite the bizarrely grisly and surreal moments, which viewers will discover for themselves.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:25 AM.

-

MICHAEL APTED: 49 UP

However it's skewed, it still can't fail

Though he’s made some other films that are remembered (The Coal Miner’s Daughter, Gorky Park, Bring on the Night, Gorillas in the Mist, Incident at Oglala, to name a few), Michaal Apted himself acknowledges that his “Up” series in which he examines the same group of British lives every seven years to see where, one by one, each of the men and women has got to since the first filmed interviews at age seven, is the most important thing he has done. Developed originally for television ("Granada's landmark documentary series") but widely seen on video and in theatrical release, Apted's Up series is a powerful and moving body of work, in its own small way a monumental study of contemporary society from the immediate post-war period till today, all in the most specific terms imaginable: individual lives and the way they've been lived. What is more interesting, really, than a life? And that means work, love, family, children, hardship, joys, all the things that matter. Is any subject more important than this?

There are certain limitations to the method. Apted has to show what his subjects want to show, and no more. With a project of this longevity it’s essential to maintain good relations. But in a way it’s a project that can’t fail. Each seven-year segment unmistakably reveals what the people have come to.

One thing that’s emerged is that the person’s life in each segment tends to have a certin distinct tone. Several of the people at 21 were clearly unhappy, or defiant, or talked wild. And Apted has seen that he can get it wrong. He is always the (unseen) interviewer, and he has been known to be intrusive or force the issue. Take one of his main people (because so open and voluble), Tony the East Ender who wanted to be a jockey and wound up driving a cab and now has moved to Spain and has grandchildren. Apted decided about Tony in 21 Up that he was going to turn to crime. Perhaps 21 is an age when certain people like to try on attitudes. In fact Tony has proven to be quite reliable and positive and safe, a model of family values, a successful entrepreneur, his marriage a partnership (both have driven London cabs) and, through think and thin (including faced infidelity) one of the group’s most stable. So Tony has moved up and up and now has transferred to Spain where he is likely to open a café.

The series has a range of types, which in part is calculated through choosing boys from public school and from council estates and foster homes. (The way the two men from foster homes have reunited is touching.) The three upperclass boys pontificating on a bench at seven is a sequence returned to frequently because their self confidence is as astonishing as it is absurd. One of these has refused to be filmed since 21 Up—and since he’s a documentary filmmaker, this Apted finds unforgivable. The others have turned out very much the way they predicted at seven, went to the schools they said they’d go to, became a barrister, and so on. There are interesting types. The public school boy who taught in Bangladesh, then in ghetto schools, who’s now switched to an elite and ancient school because he felt he was being worn down, and he wants to teach maths to boys with talent; he seemed unlikely to marry; but now is happily so with children. The man who was homeless in London at 28, who declared he was losing his sanity, who’s gone into politics -- but not because he's gone mad; he's changed a lot. The boy from the foster home who went to Australia to be with his father. The woman who lives in Scotland near her husband, but is divorced, and who accuses Apted of skewing his picture of her toward the negative.

When Apted assembles each new segment on one of the group, he edits in clips from earlier Up films on that person. How he chooses these clips is up to him, and certainly can skew the image of the person one way or another.

Yes, this isn’t rocket science. But it’s fascinating. And it just gets better and richer as we go along. Apted's Up series is essential viewing and was an obvious film to include as part of the "insanely selective" New York Film Festival for 2006.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:26 AM.

-

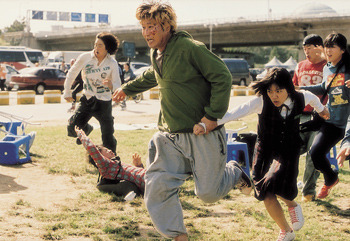

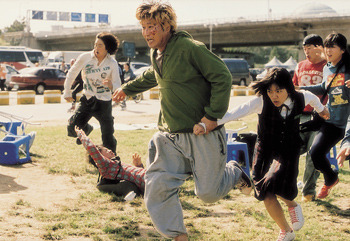

Bong Joon-ho: The Host (2006)

BONG JOON-HO: THE HOST (2006)

Populist, politically correct wild fun

Leave it to the lively Korean film industry to produce a monster movie with a populist heart and political overtones that's great fun to watch. The fact that Bong Joon-ho's The Host (whose Korean title Gwoemul just means "Monster") has been the biggest box office success in Korean history isn't just due to its high entertainment value but also to its direct appeal to the ordinary guy. Its heros are heroes in spite of themselves.

The premise is a true event: Americans dumped a bunch of toxic waste into the Han river that runs through Seoul and a scandal resulted. In the movie, a dictatorial and nutty American military chemist orders his Korean subordinate to pour gallons and gallons of formaldehyde down the dram because the bottles it was in had gotten dusty. The drain feeds directly into the Han river. The result is a huge mutant fish-lizard creature that goes on a rampage and crushes and eats people, or just catches them up in its tail and dumps them in a sewage vault.

In Fifties sci-fi/horror flicks the monster was often a stand-in for the red menace. Here it's a warning of eco-disaster and an offshoot of mindless globalization, unbridled American hegemony. Bong studied sociology at university before graduating from the Film Academy. He treats popular subjects in fresh, human-centered ways, and is a master of chaos, which makes him good at orchestrating an actioner like The Host and keeping it from turning into a special-effects fiesta. The effects are state-of-the-art, but restrained. The SFX boys wanted to do many monsters, but one was all Bong needed, and it's not enormous, but small enough to get hidden behind a sewage wall.

This never ceases to be an old-fashioned scary sci-fi genre movie with loud bangs and a creature with a terrifying mouth. But uppdated though the techniques are, it maintains an appealing silliness. The heart of Bong's movie is its human side. The story focuses on a poor working class family, two generations of men without women, a cute little girl and her aunt who's a champion with the bow and arrow. The family live in a little food shack on the edge of the big river. The Host has a number of moments that speak vividly of what it's like to be poor and to be hungry. Gang-du (Song Kang-ho) is a slightly narcoleptic dad. His father, one of several casualties in this story realistics as to loss, tells the kids he was once smart but was mentally disabled by poor nutrition as a child. When the mutant creature goes on the rampage it runs off with Gang-du's daughter, Hyun-seo (Ko A-sung). In her sewage dump prison she gets hold of a cell phone and calls Gang-du, who has to escape to hunt for her, because the authorities have imprisoned him and are injecting him with drugs.

In the bedlam that insues the media and the authorities, always acting under the instructions of the Americans, announce that an American officer has died after the first big public encounter with the monster and the autopsy reveals the presence of an unknown virus.

This is a lie, but the powers that be do all they can to perpetuate it. The common people who�re the stars of this movie have to battle the authorities as well as the monster. According to director Bong, the family of Gang-du "must fight to the death against the indifferent, calculating and manipulative Monster known as the world." The way the Americans in The Host use misinformation to manipulate people is seen by the director himself as a reference to Bush's run-up to the invasion of Iraq.

The monster is the American's creation. The hysteria is a collaboration between the government and the people.

The Host combines media-savvy political satire, human drama, adventure, and comedy. Bong juggles and interweaves all these elements with frequent injections of renewed excitement as new crises arise, the monster reappears, or the little family escapes from authorities. The monster is grotesque and menacing, moving at breakneck speed and able to flip around and swing by its tail like some kind of ludicrous yet terrifying slimy monkey.

Bong has acknowledged some debt to Shyamalan's Signs. He's been called "a Korean Spielberg," but he says that's a huge compliment to him but not to Speilberg. The film is a creative partnership between Korean technicians and Weta Workshop (King Kong, The Lord of the Rings) and The Orphanage (Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Sin City). Anyone who's seen Park Chong-wook's revenge films knows that the Korean filmmakers are already in many ways technically at the top of their game; and fans of Hong Sang-soo also know this country can do subtle, ironic relationship movies as well. What's remarkable about The Host and makes it a good choice by the Film Society of Lincoln center for the NYFF is that it's slam-bang popular filmmaking, but it knows how to make the human action real and specific in ways the Americans have lost touch with. Bong cares about the little man. He is not, like Shyamalan, looking for a spiritual message or just striving to be world famous. Because he's a populist, he wants to use mainstream genre to talk about working class strivings and problems. The family in The Host is not unlike the people in Akira Kurosawa's Do-des-ka-den, but this isn't a downbeat, alienated tale; it's mass entertainment liberally laced with thrills and chills.

Bong has used several of the stars of Park Chan-wook's revenge movies, Song Kang-ho (whom he has used before) and Bae Doon-na. And the acting is what ultimately makes this a winner. But everything works, and works well and entertainingly.

Distributed in America by Magnolia Pictures, The Host is destined for limited U.S. release in early 2007.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-26-2021 at 01:09 PM.

-

Alain Resnais: Private Fears in Public Places (2006)

Alain Resnais: Private Fears in Public Places (2006)

ALAIN RESNAIS: PRIVATE FEARS IN PUBLIC PLACES (2006)

Alienated Parisians lost in a (notional) snowdrift

In this sleek but uninvolving French film we get brief looks at a series of people. Thierry, a real estate agent (André Dusollier), is going out of his way to find an apartment for Nicole (Laura Morante) and Dan (Lambert Wilson), a couple of hard-to-please clients. Later that day Thierry’s coworker at the agency, Charlotte (Sabine Azéma), lends him a videotape of a religion-oriented musical TV show, but when he goes home and watches it the tape surprises and arouses him. His younger sister Gaëlle (Isabelle Carré) gos out after he comes home, pretending to be having fun with the girls, but she's secretly looking for love and is dating through the personal columns. Dan, who's a career soldier recently expelled from the army for unspecified reasons, whiles away his time in a hotel bar confiding his misadventures to the barman, Lionel (Pierre Arditi). Lionel has sought a volunteer from a Christian benevolent organization to care for his aging, demented and foul-mouthed father at night when he’s working at the bar, and the pious Charlotte is the one who turns up for this chore. One character influences the other without their even knowing each other. When Nicole and Dan decide to take a break in their stale relationship Dan winds up having a date with Gaëlle.

This setup may be odd but it isn’t complicated – it keeps the characters simple. But that's the trouble: we don't know in basic terms exactly who any of them are. What is the repressed Lionel’s past? What was Dan's career-ending transgression? What work does Nicole do that would enable her to seek a three-room apartment in Paris when her boyfriend's unemployed? And why is Charlotte so peculiar? The characters to begin with are unclear and the rearrangement of their relationships remains equally fuzzy. All these alienated souls are adrift. But so what?

New Wave legend Alain Resnais’ film version of English playwright Alan Ayckbourn’s play Private Fears in Public Places (Coeurs, "hearts," is the new French title) is a study of six lonely people wanly pursuing an end to their solitude. Why is it always snowing outside, and surprisingly often inside? Because it’s snowing in their hearts, of course.

Resnais has brought together six highly respected screen actors and added a Parisian gloss to the proceedings. The result unfortunately is dreary and inconclusive; use of fifty short scenes shifting back and forth among the characters is a serious bar to audience involvement. There’s something about Christianity and temptation here, focused in the apparently pivotal figure of Charlotte, who’s a saintly temptress with all kinds of unresolved issues. But then everyone’s issues are unresolved here, and the film doesn’t resolve them; it just sort of stirs them around and then ends. The inconclusive use of the polished Dusollier recalls his triumphant performance with Emmanuelle Béart and Daniel Auteuil in a really successful and moving film about cold-heartedness, Claude Sautet's 1992 Un coeur en hiver.

Apart from the somewhat annoying poutiness of Laura Morante, the cast is fine but lacking in chemistry. Dusollier and Azéma (who were entertainingly coupled in the bourgeois arrested-development film comedy Tanguy) have the most to do, but they remain enigmatic because their characters are underwritten. Their roles have comic potential that's unfortunatley undeveloped. It's hard to see how any wit could have been injected into the drying up relationhship of Dan and Nicole, and Dan's date with Gaëlle evaporates in a cloud of alcohol.

The New York Film Festival, like those of Venice and Toronto, is paying homage to the great director of Hiroshima mon amour and Last Year at Marienbad (who has not been as consistenly accomplished for the pasty fifty years as Eric Rohmer) by including this film in their rosters this year, but it seems likely to have little future with any audience outside Paris.

To err is human; the “insanely selective” ones of the NYFF jury don’t always hit the mark.

The film is being promoted by Studio Canal and opens in Paris in late November. No US distributor.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:28 AM.

-

BARBARA ALBERT: FALLING (2006)

A long day's journey into the mid-thrities

The German title Fallen means not only "to fall" but also "traps," a hint about what some of the characters have fallen into. This well-acted, intense, but slightly shallow film from Austria describes twenty-four hours shared by five thirty-something women who were friends when they were young (fourteen years back) and are reunited by the funeral of a former teacher. They decide to stay together afterward and go to a park, a wedding, a disco, etc., stay up all night, drink a lot of booze and smoke a lot of cigarettes and share a lot of memories and feelings. Barbara Albert planned Falling as a portrait of her generation (her characters are a range of types) and she used actresses whom she knew and set the action around the little town in Austria they all come from. Falling is funny, sad, strung out, tired, hysterical, and loving. It talks about a lot of things and reveals a lot about the women. But they do not tell each other everything; they don’t have to; they don’t want to. Toward the end something is revealed about one of them, who has her young teenage daughter with her, that she had hidden from the others. The best thing about the film is its natural performances. There is a lot of music, beginning with the naïve, born-again Christian chorus at the funeral singing hymns in English. Since being together evokes many memories, there are quick black and white flashbacks, fleeting flash-forwards too of things about to happen during the action of the film.

The women are the sad-faced, negative Nicole (Gabriella Hegedus), Brigitte (Birgit Minichmayhr), a shy teacher; Nina (Nina Proll), unemployed and pregnant (the father has been deported); Carmen (Kathrin Resetarits), a successful actress now working in Germany who was the wild one when she was young; and the insecure, substance-abusing Alex (Ursula Strauss), who works at a job-center. Nicole is with Daphne (Irna Strnad), her daughter, which turns out to be a violation of her parole that leads to trouble for her before the action ends and the revelation to the others that she has been in jail. An interesting detail is that Hegedus, who plays Nicole, has worked at women’s prisons, and incorporated her knowledge of women inmates into her character.

The film is intense and real (and at times ear-splittingly loud) as an evocation of a kind of feminine pre-midlife crisis bacchanale. It’s long on generational style (the way the women think and talk, the music they like) and revealed personality traits (if forcefully so more for Nicole, Carmen and Alex, than for the other two) but short on plot elements. There is plenty of atmosphere, but a meager supply of events. One would call it a process film except, what is the process? Perhaps one problem is the women have not done enough. None of them are married. They've been to Greece and Ceylon, and slept with the teacher, and had a boyfriend who died of an overdose. But so what? Few of them have achieved much, and that and their personalities give the proceedings a downbeat flavor (is that right for a whole generation? One hopes not.). Despite some lewd behavior and sexual excess and drunkenness, there are no outpoured revelations, no new developments. When it’s over, it’s over, and there’s not much to remember. And this is a shame because Albert obviously has talent, is a keen observer, produces clean, intense-looking images, works extremely well with actors (even the young one is impressive), and Austrian films are a rarity and ones about young women an even greater one. One can see the value of this as a unique entry in the year’s world film output, but it looks like Albert has done better before.

Falling has no U.S. distributor.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:28 AM.

-

David Lynch: Inland Empire (2006)

DAVID LYNCH: INLAND EMPIRE (2006)

A nightmare to remember: Lynch back on the edge

Inland Empire: it means Los Angeles, the place of Lynch’s inspiration, but also the inward realm of the mind and of dreams, the surreal world of Lynch’s imagination that uniquely inspires his visual poems. This new work, three hours long but unified by a savage and harrowing performance by Laura Dern channeling three or four or more overlapping personalities growing out of a lengthy free-standing monologue that was the film’s starting point, is proof that the man isn’t playing; hasn't lost his touch; still produces work unlike any other, work to be treasured.

DL explores a universe reachable only by going past the rational mind. It is a realm where a character, in the present case particularly the characters played by Dern (the press cliché is career-defining performance), turns into other characters and turns again. It’s a realm where where another world lies behind the sound stage and that other world is another life, another identity, another set of terrors. And we go there; we come back; and we go there again.

After becoming the desperate monologist, Dern also became "Nikki," a movie star chosen with "Devon" (Justin Theroux) to star in a film, On High in Blue Tomorrows, directed by "Kingsley" (Jeremy Irons). And "Kingsley" works with "Freddie" (Harry Dean Stanton) a co-director who cadges money from stagehands and actors and apologizes saying, "I used to carry my own weight." On High in Blue Tomorrows turns out to be a remake of a doomed film, 4/7, never finished because both stars were murdered, and based on a Polish gypsy folktale. In the film Nikki, as "Sue," is cheating on her husband, and during the shoot Nikki's "real life" husband warns her not to do it for real. But of course she does: the film relationship parallels "real life," and the stars find they’re confusing themselves with their film characters, just as it happens in Giuseppe Piccioni's recent film, La vita che vorrei.

That expletive-strewn 14-page ("single-spaced") ur-monologue that anchors the film was shot in the back of DL’s house with a Sony PD-150 digital video camera he’d started to use in connection with his website, davidlynch.com (now http://www.davidlynch.de"), "a common midrange model" that sells now for $2,724. The monologue became the ground of being and the Sony became the simple visual tool that gave Inland Empire its content and its visual style. Lynch has switched to DV for good, saying a sad farewell to the glorious beauties and cumbersome complexities of celluloid, and for this film embraced DV's limitations. He does not try to make it look like film. DL admits people say the quality is "not so good." "but it’s a different quality. It reminds me," he says, "of early 35- millimeter film. You see different things. It talks to you differently" (Lim).

This reversion, if you will, to a cruder visual medium (but one that's in many ways more fluid, both for the actors – who can work through without pauses – and the editor – who has handy software – and the crew – who can be fewer, and work lighter), has stirred up the director’s creative juices, brought him back in a way to the raw energies and immediacy of Eraserhead. Thus it's a return to youthful beginnings and yet something completely new. It's burning the bridges and rediscovering roots at the same time, which basically is what any artist to stay alive needs to do.

Dern anchors the film, but it has many elements that need anchoring. There is the disreputable husband of the disreputable monologist, who joins a Baltic circus.There’s a woman played by Julia Ormond, who's first seen in a sleazy backyard with a screwdriver in her stomach, and later reappears as Billy’s wife. And there’s a Polish thread – which grew out of Baltic connections DL has forged and in the structure of ideas may trace back to the origins of the film of Devon and Sue and hence be the ur-4/7. There’s a weeping Polish prostitute, watching a TV monitor on which appears a sitcom shot on a stage with people wearing rabbit heads; a laugh track creates a disquieting effect because the laughs come at "meaningless" points, giving the lines a sinister ring. Later the screen shows Sue. Slant magazine's Ed Gonzales alludes to the monitor as one of various "portals" through which characters merge into other worlds (go through the looking-glass; fall through rabbit-holes). Clearly it’s all in the editing, and those who feel DL’s creations are chaotic and portentously meaningless overlook his canny sense of structure.

There’s a group of pretty prostitutes in a motel room, who talk to Laura Dern’s character and sing and dance, "Do the Locomotion," and then at the end lipsynch Nina Simone's "Sinner Man" behind the closing credits -- one of the great closing credits of recent decades, a rollicking, gorgeous episode, which cheers you up but still contains flashes (Laura’s face) that haunt you with memories of the strangeness and terror that’s passed.

These are some of the interlocking boxes of Inland Empire. DL mocks the idea of the “real” while using the concept to slide in between worlds.

All this is gloriously cinematic.

The film "technically" has no US distributor, though it has many European ones and the French Studio Canal signed on early at the stage when DL said he was using DV and didn’t know what he was doing.

The whole of Inland Empire perhaps "resembles the cosmic free fall of the mind-warping final act in Mulholland Drive" (Lim), but on the other hand it has someone to "identify" with (if you can stand the ride) in Laura Dern, who dominates the film and threads it together. Her full-ranged performance is sure to gain much mention at year’s end.

A few more notes. The strange neighbor of Nikki who visits the actress’s palatial mansion early in the film to drop dire hints about her upcoming role: Grace Zabriskie (Sarah Palmer in "Twin Peaks" and a Lynch regular). People may not have seen Rabbits (2002), a 50-minute recent film by Lynch starring people in rabbit suits or the animated series Dumbland, but these are sources. On Lynch’s personal website, he proposed a blog discussion: "If two dog houses are on fire, and dogs are dying, should one automatically set fire to a third dog house and destroy it? Amid the various quirky replies, the perception emerged that Lynch was referring to the response to 9/11. Lynch is concerned about 9/11. He may be open to some of the more bizarre theories about the Pentagon attack.

After fifteen years of disappointment with and doubt about DL, it is possible to love his work again. And hard not to love his own personal jolly, simple manner. The man is clear. From what he says, his 33 years of twice-daily practice of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s "Transcendental Meditation" has made him a serene man, but that only makes it easier to access the horror within. Hence the paradox of a smiling, good-natured fellow with terrifying stories to tell. Recommended as a basic update on things Lynch and used as a source above (along with Lynch's press conference at the NYFF): the NYTimes interview piece about DL by Dennis Lim.

[Links updated 30 Mar. 2017.]

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-31-2017 at 03:59 PM.

-

Johnnie To: Triad Election (2006)

JOHNNIE TO: TRIAD ELECTION (2006)

Bloody game: an elegant repetition of an old routine

[ P O S S I B L E . . . S P O I L E R S ]

It may seem odd for the selective New York Film Festival to include what in many ways is a fairly standard Hong Kong crime movie, working in the familiar genre of Triad gang stories. What is new here, perhaps, if it is really new, is that not only does the main character make his choices in order to create new relationships with the Chinese mainland, but he also dreams of becoming a pure businessman, and wants his son not to be a successful gang leader like him but an attorney. Even if we didn’t see the original film of which this is the follow-up, we soon learn that the Wo Shing Society undergoes leadership changes every two years by a vote of its key members, and current leader Lok (Simon Yam) is about to finish his term. As the time comes though, Lok wants to hold onto his power, which leads to a personality change. He turns very nasty. But Jimmy turns even nastier.

Lok has to select a potential candidate amongst his 5 godsons, and Jimmy (Louis Koo) already rich from pirated porn sales, seems the best qualified to bring in new business for the Society. However, his interest is only in making money, initially that is, until he's seduced by the fact that with power, the mainland Chinese will give him more respect, and with that, the potential for more business. In fact a key mainland player tells him he cannot come back to deal with them unless he is president of the society. It is only in the hopes of becoming more a businessman that Jimmy accepts the idea of a two-year term as Wo Shing leader. But he must fight for that, because of Lok’s change of heart.

The irony is that after Jimmy succeeds, he finds he has fallen into a trap.

To what extent this has anything to do with actual events, or is a reference to the new relationships since 1997’s changeover to mainland control of Hong Kong, is uncertain. But the kernel idea of the film according to To was a police commissioner's remark to him that the criminal class would be important to the stability of the new Hong Kong. To feels that the Triad system is dying, perhaps also as some Italians feel the Mafia’s glory days are over. But as an old Arab proverb says, “Evil is ancient.” And in keeping with this principle is director To’s notion of the role played by destiny in life, which relates to Jimmy. Jimmy’s destiny comes from his birth. His father was a criminal, and he is a criminal. His plan of eventually becoming merely a successful businessman is therefore doomed, because it is not his destiny, nor will it, most likely, be his son’s.

This film was entitled Triad Election as presented, but the international title Election II is more accurate, given that this is a sequel, with the same main characters, to Election. Apparently this newer film was issued in a “sanitized version” which dwelt more on the political machinations than on the usual violence. In the version shown at the NYFF the violence was restored, and it is some of the most horrific imaginable, including as it does men chained to mad dogs (was Abu Ghraib an inspiration?) and a man who is beaten to a pulp with mallets and then dismembered with knives, his severed limbs run through a meat grinder and fed to the dogs. There is a scene in the new Scorsese The Departed where Jack Nicholson smashes Leonardo DiCapro’s already broken hand, and another when he appears with his shirt disheveled and covered with splattered blood. But that’s nothing compared to these Hong Kong Triad tortures, which are shown in vivid detail. Unlike the showy acting in The Departed the characters in Triad Election tend to speak in quick monosyllables. Then of course, Chinese is a monosyllabic language. But there are no caressing poetic effusions, no love scenes, only politics, a few hugs, and the nihilistic isolation of ultra-cruelty. Even the ganglords' wealth is shown only by their riding in big dark expensive cars.

The film begins boringly, as such films often do, with a meeting outdoors between syndicate members and officials. It is only as time goes on that the violence begins and we get the juice and momentum of a real crime movie. That also includes throwing an old man down many flights of stairs to kill him. All this is elegantly filmed; the often chiaroscuro wide-screen cinematography is impeccable, and Louis Ko as Jimmy is as handsome as the young Alain Delon. The acting is of uniformly high quality, as are the other aspects. But despite that the experience the film provides is rather routine. Godfather-esque moments notwithstanding, there is here none of the powerful characterization, the moral content, and the fierce forward momentum of John Woo. What we have here is an homage to the peak performance of a genre artist – except that by reports Election, the first film, is superior. It’s not likely that this film will make many new converts to the genre or the director.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:30 AM.

-

Tahani Rached: These Girls (2006)

TAHANI RACHED: THESE GIRLS (2006)

The spirit and sadness and spice of street life

These seven young women living on the street in Cairo are warm and spirited. They are sad but somehow admirable. The documentary film, made by a mostly female crew whose members had spent weeks gaining the girls’ confidence before they began shooting, shows Shari’ Orabi (the street where they hang out) and the girls most often at dawn or twilight or night, tinged with yellow, with glimpses of derelict cars, sunlight cast on men in a cheap café puffing on sheeshas, little children playing or learning to walk. Not since Duane Michal’s perceptive little photography book Merveilles D'Egypte has anyone captured the quirky, shabby beauty of ordinary Cairene street life. No one has captured the street girls of Cairo before. Here, Tata, Maryam, Abeer, Dunya, and the others and some boys address the camera and talk about their lives. Why are they there? How do they spend their time? Do they get by? What hardships do they face? There are different answers. To “Why?” there may be no good answers.

This is a new phenomenon. Girls have only lived on the street in Cairo for the last fifteen years. Rached said this in an interview. The film is without narration. It wanders back and forth between the upbeat and the sad, with understated intervals of Felliniesque music by Tamer Karawan, which echo the girls’ moments of good cheer and whimsy. We do not really see much about what they do, except sniff glue and smoke joints and take pills, fight, get pregnant, take care of their babies, dream of their jailed boyfriends, get their hair done, ride a horse, sing and dance, boogie down – all these things happen. There is a social fabric, Rached also has said. People care for these girls, step in from time to time. Sometimes they have to be protected from their fathers, who become enraged if they are pregnant. The trouble is, they aren’t married, and they don’t’ know who the father is. They all had some reason to leave home. But they wouldn’t have done so and stayed if they weren’t strong enough to survive here. One girl, one of the prettiest, has her hair cut short, and has posed as a boy to protect herself. Others have scars on their faces from men who have abused and raped them. Some of them become scam artists from time to time, practice prostitution, or beg to get money for food and for their children’s needs. (Most of this we don’t see on film.) they are all pretty articulate – one little boy who briefly speaks, stunningly so.

The film draws no conclusions, and Rached in interview had no solutions to offer. She only said that the strength of the girls and the continuing social fabric indicate that there is hope of change for the better. When the film was shown in Cairo, she said, the girls laughed and joked about it as if it were a home movie. The public received it warmly. Speaking of warmth, a special word has to be said about Hind, a young middle-class woman of conservative dress, matronly girth, and devout beliefs with no background in sociology who simply decided on her own to be responsible for the girls. She comes to visit from time to time, even now that she has a boy of her own, listens to their problems, intercedes with their parents, advises them what to do. The round smiling face of Hind is the image of pure love. These Girls is touching, beautiful, heartwarming, and sad. There’s no message here, and no statistics, but the filmmaker, herself Egyptian, is not being coy about her sympathy.

These Girls is the first film produced by the recently resurrected Studio Misr, once the home of classic Egyptian cinema, since fallen into total decline, now reactivated and restored under the leadership of Karim Gamal El Din. Al-Banate Dol, the title in Egyptian Arabic dialect, could also mean “Those Girls,” which from one angle might be better. But the English subtitles, which are essential to this talkative and highly colloquial film, are excellent.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:31 AM.

-

Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Climates (2006)

NURI BILGE CEYLAN: CLIMATES (2006)

Zero by the hygrometer

Turkish director Ceylan is uncompromising in his alienated view of relationships here. Issa, the hero, if we may call him that, played by Ceylan himself, and his luminous-faced, smiling, but quick to weep girlfriend Bahar (Ceylan’s wife Ebru), see their life together fail while they are on a holiday trip by the sea, and move apart when they return to Istanbul. Later Issa tries again, going to a remote snowy location in the East where Bahar is at work on a long TV project, but they part again. And the snow comes down. The End. In between Issa goes back to a former lover, Serap (Nazan Kesal), and they have a violent sex session on the floor. Is it a bitch-fight, a rape, or passion? It’s hard to say. (There are moments of dry humor too.) There is other violence: Bahar causes an accident when she and Issa are riding a motorcycle by momentarily blinding him. But in between, there is much silence. Ceylan is a master of the long stare and of silences. He requires patience. But there’s a rhythm to his melancholy and a keen sense of the visual that can be satisfying.

What makes you care about the silences is that they seem real. The sedate pace of the film reminds one that relationships in fact take a long time to develop. They don't generally begin or end overnight. But the non-responses are so excruciating at times one wishes these people would just try to say something, anything.

There is a decrepit quality about Ceylan’s perpetually downcast, unshaven hero. He is drenched in ennui, and unwilling to seem vulnerable. Issa is older than Bahar, yet he has yet to finish his thesis. He teaches classes at the university. He's a pretentious loser who's not ready to put much energy into his pretense. (There may be a kind of glamour about this kind of character for ordinary people -- for ambitious university students, for instance. It's the glamour of existentialism; of Camus' Stranger.) Issa photographs old buildings and ruins. But he is going nowhere. Precisely for that reason he assures Bahar when he returns to her that he has changed, and can change some more. He lies and says he hasn’t seen Serap again (he had an affair with with Serap that Bashar knows about before this last encounter, so she can guess what has happened).

Ceylan is at home with dark and cold. Issa's small hotel room in the cold snowy East is wonderfully gloomy as he sits there in the dim light from outside. The crunch of the snow, like the tiny crackle of a burning cigarette, is a vivid reminder of an unfriendly world. The tinkle of a little music box smuggled in from the Gulf countries shows how weak is the chance of a reconciliation. When Issa meets Bahar with photos of their vacation and the gift of the music box, she goes off leaving them both on the table. No time for a second glass of tea. When he appeals to her the next day in a small van, the futility of his plea is cuningly underlined by being constantly interupted by people opening the door and stuffing in equipment for the next shoot.

As Anthony Lane said about Ceylan’s Distant (Uzak), winner of the Jury Prize at Cannes in 2003, which I have not seen, his world is unfamiliar. It might resemble Tarkovsky (a clip from whose Stalker appears in the previous film) but there are Turkish mountains and minarets in the background. The HD photography is quite beautiful, especially in the exteriors and the snow scenes. Obviously a festival favorite; and this is good festival stuff. But Ceylan seems not yet to have caught on with American arthouse audiences. This from the sound of it is a more accessible film than Distant. But if the exposure isn’t there, audiences won’t have a chance to respond, and so far this Turkish writer/director is the specialty of a small clique of devotes. It has a distributor, though: Zeitgeist Films.

Climates (Ikimler) won the Fipresci Award at Cannes this year.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:32 AM.

-

GUILLERMO DEL TORO: PAN'S LABYRINTH (2006)

Dreams in red; memories in blue: fascism and a child's escapes

Pan’s Labyrinth (El Laberinto del Fauno) is an unusual blend of fairy tale and nightmarish modern history – a well-produced, well-acted amalgam with seamless and powerful use of sound, image and special effect that seems likely to impress some American art-house audiences and fans or the Mexican director’s earlier Spanish-language films, Cronos and The Devil’s Backbone. Like the latter, this is colored by the Spanish Civil War. Franco’s men have won, but the Republicans are still fighting and the nasty Captain Vidal (Sergi Lopez) heads a small company of fascist forces headquartered in a hillside mill who are trying to wipe out a band of partisans operating nearby. As the film begins a pair of period Rolls Royces carries Carmen (Ariadna Gil), the new wife of Vidal, pregnant and ill. With her is her bookish, reserved daughter Ofelia (Ivan Baquero). Perhaps to escape the ugly world of the Captain, who immediately reveals himself to be not just a stiff meanie, but a chauvinist and a sadistic brute, Ofelia, already followed by a large clicking fairy-insect on the ride, retreats into the fantasy world of her books, which soon becomes the film's alternative universe. Playing outdoors near a damp labyrinth, Ofelia encounters an aged Faun (Pan; del Toro regular Doug Jones, in mechanized and digitalized gear) who tells her she is a lost princess who must perform three dangerous tasks to be restored to power and return to her underground home.

The movie could be seen as a sinister spin on the Alice books or perhaps as Disney-meets-Bunuel (though Bunuel isn’t really a source). This is magic realism with a bloody streak and a free play of imagination. Del Toro blends his strongest personal models here – the influences of exiled Spanish Republicans who were mentors to him in his youth; fairly tales and legends; comic books; even video games play into the mixture. If the result feels somewhat indigestible, it’s not because the writer-director hasn’t given his historical and fantasy worlds equal weight, but because their coexistence is both hard to credit and too vivid. Events on both sides of the looking-glass are equally horrific, and the flow back and forth is smooth. And a strong feature of the film is that despite its use of state-of-the-art special effects, they are handled with a certain tact and restraint.

While Ofelia is performing her tasks, including an encounter with a giant toad and a terrifying Pale Man (Jones again) with eyes in his palms, Captain Vidal is losing ground against the partisans, who are helped by his housekeeper Mercedes (Maribel Verdu of Y Tu Mamá También) and his doctor (Alex Angulo); Vidal personally and zestfully carries out medieval-style tortures to extract information from captured fighters. Meanwhile the ailing, pregnant Carmen is a virtual prisoner, and it’s clear Vidal only wants a male son and doesn’t care if she dies in childbirth. To protect her future brother, Ofelia uses a large, squirmy root given her by the Faun that looks like a human fetus, and prays for the survival of her mother.

Those who are eager for the downfall of the evil Captain are not likely to be disappointed, but this is a bloody, disturbing story in which there are few survivors and is absolutely not a fairy tale for children. Even more creepy than the unpredictable psychopath of With a Friend Like Harry here, Sergi Lopez is one of the best screen villains now working: his Captain Vidal is a disturbing if unvarying blend of Freudian obsession and sheer cruelty. Is this what men – or fascists – are like? (Scenes of the fantasy world are in warm colors with rounded 'feminine' shapes predominant; the fascists’ realm is in blues and 'male' right angles.)

While the story moves along with jaw-dropping vividness and del Toro never loses touch with his own imagination, the family relationships have no more depth than a fairy tale. A less grandly visual film with less spectacular effects might have interrelated real and imaginary worlds in more thought-provoking ways. It’s not entirely clear what Ofelia’s attitudes toward the actual setting are. Nonetheless, despite its horrific details and its strange combination of the childlike and the political, this is, overall, a visual and auditory treat, indebted to many sources yet not quite like anything else. It had a a kind of festive grandeur that made it a suitable closing night presentation for the New York Film Festival, 2006.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:34 AM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks