-

49th San Francisco International Film Festival 2006

____________

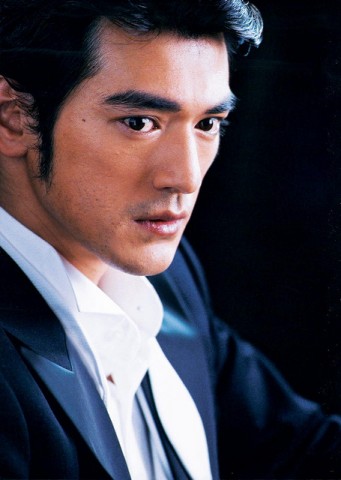

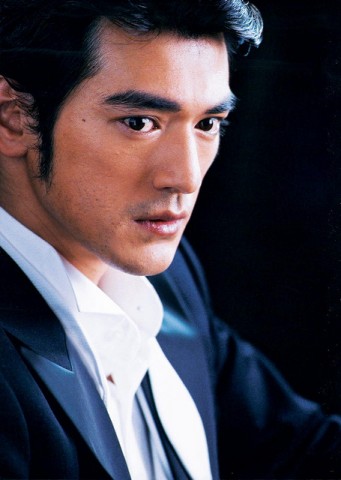

Opening night's Perhaps Love featured Takeshi Kaneshiro

SFIFF 2006: LINKED INDEX TO REVIEWS

All About Love (Daniel Yu 2005)

Betrayal, The (Philippe Faucon 2005)

Beyond the Call (Adrian Belic 2006)

Brothers of the Head (Keith Fulton, Lous Pepe 2005)

Cycling Chronicles: Landscapes the Boy Saw (Koji Wakamatsu 2005)

Dignitiy of the Nobodies (Fernando E. Solanas 2005)

Factotum (Bent Hamer 2005)

Favela Rising (Jeff Zimbalist, Matt Mochary 2005)

Gabrielle (Patrice Chéreau 2005)

Half Nelson (Ryan Fleck 2006)

Iberia (Carlos Saura 2005)

Illumination (Pascale Breton 2005)

Iraq in Fragments (John Longley 2005)

Life I Want, The (Giuseppe Piccioni 2004)

News from Afar (Ricardo Benet 2004)

Northeast (Juan Diego Solanas 2005)

One Long Winter Without Fire (Greg Zglinski 2004)

Perfect Couple, A (Nobuhiro Suwa 2005)

Petit Lieutenant, Le (Xavier Beauvois 2005)

Play (Alicia Scherson 2005)

Regular Lovers (Philippe Garrel 2005)

Romance and Cigarettes (John Turturro 2005)

Sa-Kwa (Kang Yi-Kwan 2005)

See You in Space (Ég veled! József Pacskovszky 2005)

Shooting Under Fire (Sacha Mirzoeff, Bettina Borgfeld 2005)

Sun, The (Alexandr Sokurov 2004)

Taking Father Home (Ming Liang 2005)

Underground Game (Roberto Gervitz 2005)

Wayward Cloud (Tsai Ming-liang 2005)

INTRODUCTION

by Chris Knipp

PICKING AND CHOOSING

In reporting on the 49th annual San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF) I’m responding to Jonathan Rosenbaum’s frequently repeated warning that what we get in US movie theaters doesn't show the full range and quality of world filmmaking. But my comments will be colored by the fact that my personal goal remains that of seeing the best of new films regardless of where they come from or where I get to see them.

The SFIFF's ubiquitous flyer claims to offer “227 unique films.” Guess what: uniqueness is by definition a very rare quality, and you're not going to find that many new films anywhere that are either great or unique — though "unique" (if used very loosely) is a safer word because if a movie isn't great, maybe it's different. Quality is an issue to me. And that means choosing well. But the trouble is that with two weeks of public screenings and 227 films there's pressure and little time. How does one choose?

To give some picture of the festival's all-over quality, I began by not choosing. The SFIFF pre-festival press screenings appeared to be basically a random list of offerings and I've been attending as many of them as I could, plus viewing some available VHS tapes of festival selections before the public screenings began.

This initial sampling leads me to conclude that at best maybe only ten percent of the total offerings are really exciting—“unique” in a positive sense. But the NYFF, which focused on nothing but what the committee of the Film Society deemed to be the very best of the world's films for 2005, chose only twenty-five. So that ten percent can be very important.

Last year I realized there are festival lemons, truly disastrous movies that are passed from festival to festival with the same continually augmented hype until they either get shot down by outspoken and visible big city critics (if anyone is even paying attention) — or festival organizers move on to a new crop of the next year's lemons. Making my selections of what else to see during the intense two-week period of the festival public screenings my humblest hope is to avoid lemons — or failing that, to call attention to them. Such is the nature of a film festival with many offerings.

At the other extreme of course one hopes for real finds — the one out of ten that really mattered. Others are worthwhile or fun, but haven't caused a major rise in blood pressure — and too many have been disappointments or even fiascos. That's a kind of uniqueness I can do without. But of course those who put together a big film festival aren't looking for uniqueness. They're looking for a wide range, and trying to provide opportunities for new artists and new directions -- all of which is commendable.

With this large a selection there is also a diminishing chance that the most outstanding offerings will be new to festival-goers. Clearly some of the best selections have been seen elsewhere; and without having attended Cannes, Toronto, Berlin, or Tribeca, I already know that Le Petit Lieutenant is terrific from being at the Rendez-Vous and I know that Gabrielle, The Sun, and Regular Lovers are very fine films from seeing the NYFF's official selections last year. So far, prior to the public screenings, I can only observe that one way or another I've seen 18 of the selections and that I can heartily recommend one that was new to me. That was Alicia Scherson's Play, which represents the work of a brilliant new director, and discoveries like her are why one goes to festivals. Or that's why I go, anyway.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-11-2015 at 06:20 PM.

-

[To be shown at the San Francisco International Film Festival April 23, 26, and 28 and May 3, 2006.]

ALICIA SCHERSON: PLAY

Thirty-two-year-old Chilean filmmaker Alicia Scherson has made an extraordinarily accomplished and delightful first feature. Let's not try to start out by declaring what it's "about": it's too rich and delicate for that to be anything but a travesty. Let's just mention that Play won the Best New Narrative Filmmaker award at the Tribeca festival a year ago but still has no US distribution -- and hence, its appearance at the upcoming 49th San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF). Fresh, rich in invention, sure in its unique tone, Play is a significant addition to world cinema and marks Alicia Scherson out as one of Latin America's exciting new filmmakers. It deserves to be widely seen. Like all great filmmakers, Scherson knows well how important time is -- how a movie is all about time -- and can play the game of time. In Play we're always in the present, always absorbed; the game is always in play.

If Play seems to be about "nothing," look again. Antonioni's L'Avventura and Fellini's La dolce vita were about "nothing" too. Scherson has modulated Antonioni's boredom into bemused loneliness and Fellini's wealthy idleness into a twenty-first century urban anomie of easy meetings and easy separations. But again, the generalizations feel wrong and should be held till much later. Clearly Scherson sees life with a precision and wit even the greatest directors might envy.

In a way the real protagonist of Play is the city of Santiago, Chile. Scherson conceived her film, in which several people wander around the city, when on a Fulbright in Chicago, thinking about Santiago. Her male protagonist, Tristán (Andres Ulloa), wakes up in the arms of his wife Irene (Aline Kupperhein) feeling terribly sad. He goes to work -- he's an architect on a construction site but a strike is called and later he gets knocked down by a drunk, and loses consciousness after running into a post. Awakening in the street the next day with a scar on his head, he goes into what the French call a fugue -- wandering around the city, getting drunk, no longer quite caring who he is -- and seeming to lose his identity, since he isn't working, he isn't with his wife or at home, and around a dive bar he has begun to frequent people keep mistaking him for somebody named "Walter." He spends the night in his old room at the house of his blind, charming mother, (the very accomplished Coca Guazzini) who now has a hunky magician living with her (Jorge Allis).

Meanwhile Cristina (Viviana Herrera), a young Indian woman from the southern hinterland whose "story" the movie follows from the start in parallel with Tristán's, is paid to care for Milos (Francisco Copello) an old, ill Hungarian man. Out for a walk, she comes across the abandoned briefcase of Tristán in a dumpster and at once lays out its contents and begins smoking his cigarettes and lighting them with his lighter and listening to his MP3 with his big headphones. Cristiana is sweet but a loner, walking a lot, playing the "flippy" Japanese video games in the center of town. An observer, she wants to return the briefcase, but she can't resist taking time to analyze its contents first and winds up stalking Tristán and secretly, invisibly, partially inhabiting his now disoriented life. In the meantime she cares for her sick man, reading to him from the National Geographic about an Amazonian tribe wiped out by invading white people. She goes on listening to music on Tristan's headphones and starts a running conversation with a sexy gardener, Manuel (J. Pablo Quezada), near Milos' building. (All Scherson's men are attractive, her women too.) A mercurial, honest fellow, as full of passion and life as Tristán is full of passionate ennui, the gardener likes Cristina, but declares her to be strange. At one point they start kissing, and then she immediately says goodbye and walks away.

Scherson mocks her own device of having Cristina follow Tristán and Irene at one point by having the three following each other, Indian file. She majored in biology in college, and she's above all a careful observer, neither making fun nor drawing heavy conclusions. Significant changes happen for both Tristán and Cristina before the movie ends. There are no conventional "resolutions." And yet things feel wonderfully resolved. It's a mark of Scherson's brilliance in design that even in the very last few minutes we're still curious to learn -- and learning -- important things about both the main characters -- yet can't really say for sure where they're going to go from here. The great thing is that through all the playful randomness of the narrative, we never lose our focus on the two contrasting moods of Tristán's lost melancholy and Cristina's busy but disoriented contentment with urban life.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-12-2009 at 11:36 AM.

-

GIUSEPPE PICCIONI: THE LIFE I WANT/LA VITA CHE VORREI (2004)

Very instructive

This throught-provoking, informative movie about romance, acting, and filmmaking seems not to have traveled well, but it's really full of interest. It got some award nominations in Italy and a significant one in Berlin and the two actors, Luigi Lo Cascio and Sandra Ceccarelli, who’ve appeared together frequently before, have their fans—but also their enemies. “Lento noioso e pesante” a viewer posted on the Italian movie site FilmUp—slow, boring, and heavy. It is that, at times, and at times gave me the feeling that I was either on drugs or having a very bad dream. It’s so incestuously self-referential and claustrophobic it’s chilling—and numbing; but it’s also a master class on what a scary convoluted experience it would be to have an affair with another actor while making a movie in which the two of you are having an affair—in costume, in another century. What is real? Before the two shoot the last scene of the story based on La Traviata in which the girlfriend is dying and the rejected lover weeps over her deathbed, the actress has just told the actor that she is through with him and never wants to see him again. The writers and director take a very Italian and sentimental way out of this sad finale with a cute, upbeat coda, but the actor, Lo Cascio’s character, who has told the actress earlier that he scorns actors who”really” cry in crying scenes, obviously is weeping “real” tears in the deathbed scene. The character, the modern day actor, that is, is constantly getting phone calls from an “admirer” who tells him his acting is worthless. And on FilmUp, sure enough, Lo Cascio himself gets comments about how talentless he is. In fact, Lo Cascio and Ceccarelli perform acting gymnastics in this movie that will knock your eyes out and the beautiful and expressive Ceccarelli was nominated for the 2005 European Film Academy Best Actress Award for this performance. And yet, the movie is so obsessive that it can bore you to tears at times too, and what may doom it aside from its meta-linguistic focus on an art form is that basically it’s a chick flick, a Cosmo tale about a sensitive and naďve woman at the whim of a worldly, self-centered man. I can see why Jennifer and Brad broke up, after this. Not somehow a movie that makes your heart sing, but need-to-know informaiton for any film buff.

Showing at the SFIFF four times at two venues, this would be a worthwhile choice for anyone who likes fairly serious mainstream European films that may not ever be showing in US theaters. And it should appeal to anyone who wants a look at the glamour and stress of filmmaking from an Italian perspective.

Sat, Apr 22 / 9:15 / Kabuki / LIFE22K

Mon, Apr 24 / 8:30 / Kabuki / LIFE24K

Thu, Apr 27 / 6:00 / Kabuki / LIFE27K

Sun, Apr 30 / 7:00 / Aquarius / LIFE30A

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2006 at 11:53 AM.

-

Keith Fulton, Louis Pepe: Brothers of the Head (2005)

THE TREADAWAY TWINS IN BROTHERS OF THE HEAD

A band that's really together

Experts can outline for you the elaborate history of rock docs and mock rock docs. Suffice it to say that Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe's Brothers of the Head goes them all one better with the kinkiness of the fantasy world it creates. It's about Seventies Siamese-twin boys from a remote area in England joined at the lower chest who're taken up by an impresario looking for something special: a musical freak show. Isn't that redundant, in the era of Lou and the Velvet and Ziggy and the New York Dolls? Well, no, because we've never seen a movie about Siamese twins before and we'll never see one about Siamese twin rock stars again. Real twins Harry and Luke Treadaway play Tom and Barry Howe, respectively, with incredible enthusiasm and scary charm. Joining them is a large band of prosthetic conjoining flesh, hidden at first but successively more boldly revealed in public performances when the initial audiences thought them a fake. Probably none of this would work if the two actors didn't look like the healthiest, happiest, prettiest English boys you could imagine. When they do the intimacy and the conflict involved in such a scene, the Treadaways know whereof they speak. The heart of the movie is watching them together in action.

The opening scene shows a lawyer tiptoeing into a damp corner of the northeast English coastline to get the dad of the two boys to sign a contract. This turns out to be a clip from "Two-Way Romeo," an unfinished fictional film about the boys' lives by Ken Russell, who talks about the "project" onscreen. A down-on-his-luck manager, Zak Bedderwick (Howard Attfield), we learn, found the actual twins and had them trained musically to develop a novelty rock band.

Later we alternate between successively creepier cuts from Russell's opus interruptus (in his version one of the boys gets a fetus growing out of his stomach) to the "real," also unfinished, documentary done in the early to mid-Seventies by American filmmaker Eddie Pasqua (Tom Bower) about the boys' shaky beginnings -- they're lodged in a big empty mansion where their rough working class musical manager Spitz (Stephen Eagles) beats Barry, the more obstreperous twin, to keep him in line -- and ultimate rise and hectic meltdown of hysteria, emotional conflict, sex, drugs, and inevitable, obligatory breathless self-destruction.

Later after their talent-less-ness is patiently trained out of them and Tom masters guitar and Barry does lead vocals, they sing together and get so much into the whole performance thing (Roeg's Performance may come to mind--something of the same hothouse surreal sensuality is evoked) along with the high of public appearance-cum-substance abuse, the twins are having a mad, wild good time.. But the more they enjoy themselves -- and this is what undercuts the creepiness: the sense of pure joy of self realization -- the more being forever conjoined becomes both raison-d'ętre and curse for the pair.

The film's ultimate guilty pleasure is absorbing a sense of the many complex levels of physical and psychic interaction Siamese twins (especially in such an intense lifestyle) would have, which the real twin actors are able to play convincingly: Tom and Barry go from finishing each other's sentences to erotic acts we can only imagine. They eventually become a manic pre-punk pair in a band known as Bang Bang, which plays in successively larger clubs, as the boys graduate from chain smoking to drinking to lines of coke and pills, feverish sex and psychosexual warfare.

An attractive woman, Laura Ashworth (Diana Kent, Tania Emery) comes along to do an academic treatise on the pair as a study of "the exploitation of the handicapped." To quiet her the manager hires her on with the crew and she falls in love with Tom. Once they're part of the music scene all kinds of pleasure come the boys' way along with mood swings, especially from the always unstable Barry, that challenge the power of their togetherness. A surgeon speaks about the unfeasibility of separating the two, especially now they're grown, since they share a single liver and Barry has a congenital heart defect; but later investigation reveals that Laura indeed was looking into the possibility of surgery and contacting this very surgeon, no doubt with a view to having Tom all to herself. She was banished for her pains. A sequence perhaps suggestive of Frank's Cocksucker Blues about the early Stones on tour hints at the obvious point that if one boy of the pair had sex, they both would, and the natural pattern was a polymorphous foursome. There's freaky sex for you. All of which brings back the Seventies as vividly as any almost-real fantasy could.

Kink in this case would especially include that sub-genre of twin fantasies, and this one constantly tickles out thoughts of the queerness of glam rock, (the whole Iggy/Ziggy thing) -- or, as Pepe said at a festival Q&A, "When you strap two good-looking 20-year-olds to each other, a certain subtext starts to emerge." Tom and Barry are perpetually hugging and touching each other because they're conjoined. They're adept at moving together and you even see them running and cavorting on an English lawn.

You can laugh at the genre but with the sleazy-beautiful mock-Seventies images and the twin actors' natural verbal and physical volatility, Fulton and Pepe really pull you into this story, which was drawn from a novel by Brian Aldiss (who is a character played here by James Greene as the author of Kurt Russell's movie) and adapted for the screen by Tony Grisoni.

The images are ably handled by Anthony Dod Mantle, who shot 28 Days Later, Dogville, and Manderlay but gets to play with styles more here, producing footage that combines current talking heads with beautifully faked Seventies-style footage from the presumably unfinished documentary.

This one isn't likely to draw as mainstream a crowd as Fulton and Pepe's previous success, Lost in La Mancha, but it's guaranteed instant cult status. If you like kink, you like the Seventies, and you like proto-punk, Brothers of the Head is the cult mock rock doc for you.

SHOWTIMES

Sat, Apr 29 / 9:15 / Kabuki / BROT29K

Tue, May 02 / 6:30 / Kabuki / BROT02K

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-01-2017 at 12:20 AM.

-

Zeff Zimbalist, Matt Mochary: Favela Rising

Not just a sense of rhythm

Favela Rising is a documentary about the slums of Rio, the favelas, specifically the most violent one, Vigário Geral. According to this film, a lot more kids have died violently in Rio's favelas over the last decade or so than in Israel/Palestine during the same period -- a fact astonishing if true, which shows how under-recognized this social problem is in the rest of the world. This is an important topic, especially for those who see hope in grassroots efforts to marshal the neediest and most at risk through a vibrant cultural program. This is a compelling documentary, if occasionally marred by a somewhat too personality-based version of events and by grainy digital video and film that sometimes may make you think you need (new) glasses.

Drug lords rule in the favelas and gun-toting teenage boys are the main drug dealers, like in parts of Colombia. Fernando Meirelles' City of God/Cidade de Deus has been accused of celebrating violence Cidade de Deus is another of Rio's many favelas). But the early section of Favela Rising shows that in fact favela boys do celebrate violence and want to deal drugs where the money and the action are. It's cool to carry a gun there, cool to work as a drug trafficker: it's fifty times more profitable than the earnings available by other means.

Mochary first discovered the AfroReggae movement and its leaders Anderson Sá and José Junior while visiting Rio for a conference and quickly persuaded his friend and mentor Zimbalist to quit his job and come down to help make a film with his own promise to fund it. Sá's eloquence and charisma and a startling twist in his life make him the center of the film and its chief narrator, but like the favelas themselves the film teems with other people. No doubt about the fact that Sá is a remarkable leader, organizer, and artist.

Vigário Geral is compared to Bosnia: shooting there was very dangerous. Anderson Sá's friendship and protection and caution and diplomacy in the shooting enabled the filmmakers to gain access and shoot detailed footage of their subject matters while (mostly: there were close calls) avoiding any serious confrontations with drug lords or drug-dealing cops. They also trained boys to use cameras and left them there on trips home. That resulted in 10% of the footage, including rare shots of violent incidents including police beatings. It's hard for an outsider to keep track of police massacres in Rio. There was one in the early 1990's that looms over the story and inspired Sá, who ended his own early involvement in drug trafficking to lead his cultural movement. The cops are all over the drug trade and if anybody doesn't like that the ill trained police paramilitaries come in (often wearing black ski masks) and shoot up a neighborhood, killing a lot of innocents.

This is pretty much the picture we get in Meirelles' City of God, except that this time Sá, Junior, and the other guys come in, starting in Vigário Geral but spreading out eventually to a number of other favelas to give percussion classes that attract dozens of youth -- girls as well as boys. Their AfroReggae (Grupo Cultural AfroReggae or GCAR) program, formed in 1993, is a new alternative way of life for young black men in the Rio ghettos. It leads them, the film says, to leave behind smoking, alcohol, and drugs to explode into rap, song, percussion, and gymnastics in expressive, galvanic performances. Eventually the best of the performers led by Sá wind up appearing before big local audiences with local producers, and their Banda AfroReggae has an international recording contract.

Other centers and groups have been created by or through the GCAR over the years in Vigário Geral and other favelas to seek the betterment of youth by providing training and staging performances of music, capoeira, theater, hiphop and dance at GCAR centers.

The performance arts aren't everything, just the focal point. GCAR is also a movement for broader social change Gathering public awareness through such performances, the centers also provide training in information (newspaper, radio, Internet, e-mail links), hygiene and sex education, to seek to bridge gaps between rich and poor, black and white, and to offer workshops in audio-visual work, including production of documentaries. The program is currently active in four other favelas.

There are many scenes of favela street and home life in Favela Rising and they look very much like the images in City of God with the important difference that the focus and outcome are very, very much more positive. Not that it isn't an uphill battle. And the corruption of the police, the inequities of the social system, and the indifference of the general population of Brazil are not directly addressed by any of this. But there's a scene where Sá talks to some young kids in another favela, cynical boys not enthusiastic about AfroReggae and determined to work in the drug trade as Sá himself did as a boy. Sá doesn't seem to be convincing any of them despite pointing out that traffickers don't make it to the age of fifty. But we learn that the most negative boy in this group, Richard Morales, joined the movement five months later. There's also the account of a freak accident that disabled Sá, but with a positive outcome.

The documentary isn't clinical, so we don't get a lot of facts and analysis or talking heads (besides the GCAR leaders'). But it bursts with spirit when we see the big percussion sessions and far bigger live concerts and its impact is of something bright, light-hearted and positive in the face of decades of poverty and spiraling violence. It would be great if the images were sharper and clearer and if the story were edited down a little, but this is vibrant, inspiring material and represents committed, risk-taking documentary filmmaking and it's nice that Favela Rising has been included in seven film festivals and won a number of awards, including Best New Documentary Filmmaker at the Tribeca Film Festival. It's currently being shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London. However, a wide art house audience in the US seems somewhat unlikely.

SHOWTIMES

Sat, Apr 29 / 8:00 / Baycat / -1

Mon, May 01 / 6:30 / Kabuki / FAVE01K

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-28-2018 at 09:05 PM.

-

Bent Hamer: Factotum (2005)

Jack of all trades and master of the bottle

If you remember that Bent Hamer made the little film about a Forties Scandinavian household efficiency program called Kitchen Stories, you'll be partially prepared for the dry, sardonic style of this follow-up feature, the Charles Bukowski-based epic of seedy living Factotum, in which Matt Dillon gives a stylized, restrained performance as the authorial stand-in, Hank Chinaski, and Lili Taylor and Marisa Tomei seamlessly slide into the roles of Hank's alcoholic girlfriends Jan and Laura. Bulked up with a zombie stare, stifled voice and shambling walk, Dillon is very good, if, due partly to script limitations, not as compelling as Mickey Rourke in Barbet Schroeder's Barfly. Even overweight and horribly dressed Dillon is still far too handsome to resemble the pockmarked and ugly real-life Bokowski, but you can't fault good looks in a leading man, and the film is dominated by Dillon's character, who's in every scene, his narrative voice brought in to move the episodic plot along and provide Bukowski's insistent commentary on life as he sees it.

Those episodes are all we get, and apart from brief writing and longer romantic interludes, they mainly concern a long round of short-lived jobs -- sorting pickles in a pickle factory, boxing brake shoes, dusting statues, driving a cab (a hard-on's no danger to the driver, the instructor says, but sneezing is), assembling bike parts, and so on, from which Hank is unfailingly soon fired for drunkenness or lateness, insubordination or other misdemeanors -- whereupon he goes back to writing, drinking, and sex -- which latter, Jan tells him, is no good when he gets successful as he does for a while playing the horses. (There's none of the post office sorting job Bukowski did for a long time.) For Bukowski and his alter ego being a seedy loser is a thing carried off with such chutzpah that it's sexy -- and drinking and sex are equally close ways to feed the libido. There are plenty of the ten-cent aphorisms the tireless writer worked at, and there's a plug for the Black Sparrow Press that eventually started to keep and publish his endlessly mailed out submissions and today still survives off maintaining the slob genius' oœvre in public hands.

Bokowski appeals to the young, the easily impressed, the hard drinking, and those who like the pithy sayings and ignore the arrested development. For those of bourgeois mentality and upbringing there's a certain imperishably tonic thrill in watching a man who's been down so long it looks like up; who can tell the employer who's just fired him to give him his severance check immediately so he can hurry up and get drunk; for whom no flophouse or flat is too seedy, no bibulous girlfriend a worse drunk than he. How liberating it might be not to care about losing everything, knowing that since paper and pen are nearly free you'll never stop writing: or if you lose heart for a minute or two, a dip into the works of some other writer will encourage you in the belief that you can do better. Bokowski was a tough one.

Matt Dillon is Irish enough to have seen something of the hard drinking life himself. One senses that he knows whereof he speaks and can convey the alcoholic lifestyle without irony or melodrama. There's nothing quite like Lili Taylor coming out in her underwear to fix Hank a meal. His request is for another round of pancakes. "There's still no butter," she says. "Well, they'll be extra crisp," he replies.

In a smaller but still choice role Marisa Tomei is well disguised as another drunken lady Hank goes home with, finding that she lives with a flaky French millionaire called Pierre (Didier Flamand) with a little yacht and dreams of composing an opera.

Hank's been taken off so many two bit jobs being fired has no sting left for him. Bukowski's persona is impenetrable and he's a simple survivor: he's almost utterly resistant to the forces of change his wayward lifestyle would activate in lesser beings and hence, unlike the downward spiraling drunk so movingly played by Nick Cage in Leaving Las Vegas, for instance, Bukowski's Hank in Dillon's performance cannot build toward pathos or true depth. As suggested, this film doesn't develop its sequences and relationships as thoroughly as Barfly, for which Bukowski himself wrote the screenplay, giving it a continuity and focus Factotum's more cobbled-together script doesn't quite muster.

There's something condescending and cultish in the European cultivation of the Bukowski myth in which this is another short chapter. Factotum is an occasionally amusing, at moments laugh-out-loud kind of movie that's well served by all the principals and by director Hamer's dry wit and restraint, but after the desultory and boring stretches have eventually started to pile up you may begin to say: So what? and wish the fresh novel feel of the early scenes could've been better sustained throughout. Not to fault the editing, but mightn't a native's keener ear for the rhythms of the dialogue have kept the flow going better? This is one to see if you like Matt Dillon or Bukowski; otherwise, save your time.

SHOWTIMES

Sat, Apr 22 / 9:00 / Kabuki / FACT22K

Sun, Apr 30 / 3:00 / Kabuki / FACT30K

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-25-2014 at 11:33 PM.

-

Ryan Fleck: Half Nelson (2005)

Ryan Fleck: Half Nelson (2005)

Half success

Ryan Gosling, the twenty-five-year-old Canadian-born actor remembered for the Mickey Mouse Club, Murder by Numbers, and The Notebook, gave such a memorable performance as the Jewish Nazi skinhead in Henry Bean's The Believer that it was a pity a technicality kept him from getting an Oscar nomination for it. By reputation Gosling is one of America's young actors most willing to delve deeply into a role and thoroughly commit to it, and The Believer amply proves that. But some of his performances and choices since have aroused doubt about his depth, his range, and his wisdom in choosing roles. Perhaps one of his drawbacks is his unprepossessing appearance. As a junior high teacher in a ghetto school in his new film, Ryan Fleck's Half Nelson, Gosling looks like a reedy student himself and his bland expression and his small, too-close-together eyes hardly hint at the torment that might result from living a double life as upright politically committed history teacher and off-duty full-time cokehead. What are the demons that drove him to such an addiction? All we can see are the weakness and laziness that keep him in it. When not addressing the class he can barely stay awake, so you wonder how he landed the additional job of girls' basketball coach. Gosling may have gotten into the theme of dialectic that he emphasizes in his classes enough to be able to improvise his teaching sessions, but they're mostly so simple they're embarrassing. The role is problematic. As an addict, Dan Dunne, his character, is shut down emotionally. Under those circumstances how do you convey the presence of masked feelings? There is more to Gosling and to Dunne than meets the eye here, but the movie is a disappointment.

The other actors can't support Gosling or his character either. None of the ghetto people or scenes presented in this movie -- regardless of how authentic the sets or actors -- comes across as real. Frank (Antony Mackie) is a handsome drug dealer who looks after Drey (Shareeka Epps), one of Dunne's students and a member of his basketball team whom he makes friends with after she discovers him doing crack in the girls' restroom. Mackie's Frank is too charismatic for a dealer in the hood. Drey (Shareeka Epps), a non-actress, has fresh moments, but her relationship with her teacher (Gosling) never takes off as it should because their scenes are as underwritten as the classroom sequences are pretentious. The competition between Frank and Dan to be Drey's mentor seems fatuous. Drey's brother is in jail because of working for Frank, so Frank is responsible for Drey? Dan is Drey's cokehead teacher, so he can be a role model for her? How does all that work?

Late in the movie inter-cutting between a gathering at Frank's house and an alcoholic evening for Dan at his parents', though obvious, introduces some complexity. But for the most part one can only wonder where the film is going, and the conclusion has to be it's setting up a situation, but has no where to go with it. Dan's dull bleary expression every time he enters the classroom looks real enough, but you wonder how he can convince the class that he's a good teacher. He is painfully sincere, but he hardly convinces us. The dinner with the parents show they are old lefties who were antiwar activists in the Sixties. But they don't know anything about Dan, and they're in a wine haze themselves. These scenes need to be carried further to carry emotional weight.

There are imbedded political messages in the movie. First come the important little history lessons (Attica, the CIA overthrow of Allende, Brown vs. Board of Education) delivered periodically by Dan's students that concern race and class and America's transnational political machinery. Then there's Dan's exchange with a Latina teacher he likes (Monique Curnen) about Marx and Hitler. And there's Drey's discovery of Frank's collection of humiliating blackface figurines. All these are moments that provide commentary on the relationship Dan and Drey are trying to establish, which may somehow be about to save Dan at the film's end. But director Fleck is too timid to push these points into a real shape, and what Half Nelson gives us remains only a situation, not a statement. Jittery camera-work and improvisation don't help much. Gosling may have gotten an interesting role again this time; this is not only a well-meaning movie but a pretty smart one, with its political awareness and its avoidance of classroom drama clichés. But outside the environs of Sundance mere savvy and unconventionality will only get you so far, and however well he prepared, Gosling doesn't inhabit the role of Dan and bring us to the edge of our seats the way he did with the role of Danny Balint in The Believer.

SHOWTIMES

Sun, Apr 30 / 6:15 / Kabuki / HALF30K

Tue, May 02 / 9:00 / Kabuki / HALF02K

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-08-2006 at 12:24 PM.

-

Greg Zglinski: One Long Winter without Fire

One long movie without a ray of hope

The title of this film isn't very catchy, even in the original French, but it gives fair warning of what's to come: a motion picture in which much is to be endured and little is to be enjoyed. Tout un hiver is a glimpse at cross-cultural encounters that might put a Swiss mountain farm couple's hardship into perspective when the husband gets to know some refugees from Kosovo who've suffered much greater horrors. Jean (Aurélian Recoing) and his wife Laure (Marie Matheron) have lost most of their livestock in a fire that killed their five-year-old daughter. Laure has lost her mind as a result and Jean puts her into a psychiatric clinic, a step that Laure's possessive sister Valérie (Nathalie Boulin) seems to ill approve of.

Jean must get work at a steel mill to pay debts and that is where he meets the Kosovar refugees working there, including Kastriot (Blerim Gjoci) and his sister Labinota (Gabriela Muskala). Jean is drawn to Labinota, perhaps because she seems as grief-ridden and bereft as he does. Her husband disappeared six years ago when soldiers murdered a whole community. He may have been killed, or he may have escaped, but she is still waiting. Kastriot is friendly to Jean and invites him to Kosovar social gatherings; he hides his own traumas but at times has a short fuse. The Kosovars have seen their families raped, their throats cut, their houses burned to the ground.

The harsh but spectacular Jura mountain landscapes are a big player in this film. Cinematographer Witold Pióciennik's cinematography is impeccable and sometimes uniquely lovely. His close-ups of the principals spare us nothing; there's no escape from the fact that Recoing's and Gjoci's faces are deeply and subtly expressive but the two ladies are overplaying their melodramatic roles, Matheron far too exaggeratedly nutty, and Muskala too pathetic and sweet.

Jean considers selling everything and moving somewhere else: a new start. Laure, who is perhaps beginning to become coherent again, is not enthusiastic. But like the rest of the story, this issue is something we keep going back and forth on without any resolution.

There's heavy-handed symbolism about crows against the snow, fire forbidden in the farm and big fire at the steel mill. Where is the Polish-born and trained Swiss-adopted director Zglinski going with all this? The editing is relentlessly arc-less: when we think Laure may be better we glimpse her engaging a a long mad scream of pain. Though Laure comes out of the clinic, and Jean has some warm times with the quietly accepting and ultimately cheerful Labinota, there's no sense of resolution; no sense indeed that we've gotten anywhere. Zglinski is obviously interested in the contrast between the warm Kosovars (parallel to the warmer and wilder Poles he knows from his own experience) and the more stoical and shut-down Swiss. But that's just a given, not a source of any revelations. As if the parents' terrible grief weren't enough, everything else seems exaggerated. The Kosovars are a little too celebratory and unpredictable. The insurance assessor is a dry, mincing creep out of Dickens. The possessive sister almost seems to have a lesbian attachment to Laure. The steel mill camaraderie has a consistently menacing and nasty air about it. One leaves with a sodden feel of unmitigated grimness. Tout un hiver sans feu was seen and reviewed as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival, 2005. It was shown on French TV in 2007; theatrical opening in Poland 2005.

[No US distributor]

SHOWTIMES

Sat, Apr 22 / 9:15 / PFA / ONE22P

Fri, Apr 28 / 9:45 / Kabuki / ONE28K

Mon, May 01 / 6:15 / Kabuki / ONE01K

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-25-2014 at 11:37 PM.

-

John Turturro: Romance and Cigarettes (2005)

Privileged fiasco

Turturro's Romance and Cigarettes leaves almost no impression -- unless you're bowled over by James Gandolfini singing (he hasn't much of a voice). Nick Murder (pointless surname) works as a garbage man in Queens (an occupation fleetingly referenced) and fixes bridges with Steve Buscemi, who gives him advice in dialogue that's not very well written or delivered. Nick's married to Kitty (Susan Sarandon) and has three daughters -- Mary Louise Parker, Mandy Moore, and Aida Turturro (deceased from The Sopranos, John's cousin; Turturro works himself and his little boy into the movie too at some point). What's this lively cast doing in such a fiasco? Well, Turturro has been in some good movies -- notably Do the Right Thing, Barton Fink, and The Big Lebowski -- and he has lots of friends. The Coen brothers, whom he's worked with so notably, produced.

The action begins when Kitty finds a pornographic note and realizes Nick is cheating on him. She calls in Christopher Walken for moral support. And Walken's an old song and dance man, so he adds something.

You might call this a partial, second-hand, working-class musical. It's second-hand in the sense that none of the music is original. And it's partial because not all the principal characters sing or appear in musical numbers. Buscemi, Eddie Izzard (as a minister), Mary Louise Parker don't get them. Numbers are dubs or voice-overs of songs from James Brown, Tom Jones, Englebert Humperdink, Westside Story, Saturday Night Fever, and many other sources, which evoke John Waters (especially now that he's gone musical with Hairspray) when they're performed in the down-and-dirty settings of a shabby Queens suburb. Sometimes this achieves poetry; other times, more often, it just seems odd, and Turturro hasn't Water's gift for sleaze, which might have transformed this story into high camp. It runs more to crudity, to a degree admittedly unusual for a (partial) musical, chiefly through the mistress, Tula (Kate Winslet), a gutter-mouthed shop girl from Lancashire who thinks -- and talks, in vivid detail -- of little but sex. Tula's lively, zoftig, and in her crude way a hot number. But she's awfully shallow.

There's audacity in the conception. Gandalfini singing would startle even Dr. Melfi. Certainly this is a good cast. But it's not necessarily the right cast. Gandalfini fits -- were it not for his overwhelming current association with that mansion in Jersey and with Edie Falco, who seems a more likely match for him than Sarandon. She has done working class roles (White Palace, Thelma and Louise); but she's fifteen years older than Gandalfini, and seems too classy for this setting. Izzard's out of place in leading a mixed-race Queens gospel choir. Kate Winslet's sublimely into her role, but her character is a little too tacky for the conventional musical love interest she is, by default, made to become.

There's not much of a story (one longs for John Water's ornate plot structures) and Turturro's editing is patchy -- he has a bad habit of snipping in two or three other scenes during a song to no purpose. In fact none of this would make it within two hundred miles of Broadway, though as The Mother (who appears when Nick's in hospital from OD'ing on licorice) Elaine Stritch gives her five-minute cameo a Broadway intensity and snap. Along with the vagueness in the action, the period is also undetermined, a "general retro feel," as Variety puts it -- very general, not very retro -and so not surprisingly, as is probably already obvious, the tone is also uneven.

Eventually Nick decides to give up Tula, and Kitty (Sarandon), somewhat reluctantly, takes him back. Sarandon injects some genuine feeling -- no doubt from another, more serious, movie -- into those final scenes. Winslet is a buoyant scene-stealer throughout in her (unfortunately) smaller role, and when Nick pushes her in the river in his goodbye scene with her she has an underwater singing sequence that is the movie's best moment visually -- it's gloriously improbable and quite beautiful. There's more. Bobby Carnavale is an absurd peacock as Mandy Moore's neighbor fiancé: his looks and strutting are eye-catching, but he'd need either to be less obtrusive or have more lines for the character to work in the whole thing. But -- What "whole thing" are we talking about? This effort just doesn't hold together. You keep wondering how individual scenes might have worked well somewhere else, in some other movie, where the style and tone were consistent.

Romance and Cigarettes is a privileged US indie movie, the kind that it took pull to get made and that, because of the pull, and the stars brought in as a result, gets good festival mileage and Sundance buzz, but fizzles out in the real world.

P.s.: This is Turturro's third feature as a director. Does anybody besides his mother and the respective casts and crews remember the first two?

SHOWTIMES

Sat, Apr 29 / 8:00 / Kabuki / ROMA29K

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2006 at 11:58 AM.

-

Carlos Saura: Iberia (2005)

Carlos Saura: Iberia (2005)

Worthy, but not Saura's best musical film

If Saura hadn't done anything like this before, Iberia would be a milestone. Now it still deserves inclusion to honor a great director and a great cinematic conservator of Spanish culture, but he has done a lot like this before, and though we can applaud the riches he has given us, we have to pick and choose favorites and high points among similar films which include Blood Wedding (1981)--a turning point in the director's work from social commentary to music, theater, and dance, Carmen (1983), El Amor Brujo (1986), Sevillanas (1992), Salomé (2002) and Tango (1998). I would choose Saura's 1995 Flamenco (1995) as his most unique and potent cultural document, next to which Iberia, however similar on the surface, ultimately pales.

Iberia is conceived as a series of interpretations of the music of Isaac Manuel Francisco Albéniz (1860-1909) and in particular his "Iberia" suite for piano. Isaac Albéniz was a great contributor to the externalization of Spanish musical culture -- its re-formatting for a non-Spanish audience. He moved to France in his early thirties and was influenced by French composers. HIs "Iberia" suite is an imaginative synthesis of Spanish folk music with the styles of Liszt, Dukas and d'Indy. He traveled around performing his compositions, which are a kind of beautiful standardization of Spanish rhythms and melodies, not as homogenized as Ravel's Bolero but moving in that direction. Naturally, the Spanish have repossessed Albéniz, and in Iberia, the performers reinterpret his compositions in terms of various more ethnic and regional dances and styles. But the source is a tamed and diluted form of Spanish musical and dance culture compared to the echt Spanishness of pure flamenco. Flamenco, coming out of the region of Andalusia, is a deeply felt amalgam of gitane, Hispano-Arabic, and Jewish cultures. Iberia simply is the peninsula comprising Spain, Portugal, Andorra and Gibraltar; the very concept is more diluted.

Saura's Flamenco is an unstoppably intense ethnic mix of music, singing, dancing and that peacock manner of noble preening that is the essence of Spanish style, the way a man and a woman carries himself or herself with pride verging on arrogance and elegance and panache -- even bullfights and the moves of the torero are full of it -- in a series of electric sequences without introduction or conclusion; they just are. Saura always emphasized the staginess of his collaborations with choreographer Antonio Gades and other artists. In his 1995 Flamenco he dropped any pretense of a story and simply has singers, musicians, and dancers move on and off a big sound stage with nice lighting and screens, flats, and mirrors arranged by cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, another of the Spanish filmmaker's important collaborators. The beginnings and endings of sequences in Flamenco are often rough, but atmospheric, marked only by the rumble and rustle of shuffling feet and a mixture of voices. Sometimes the film keeps feeding when a performance is over and you see the dancer bend over, sigh, or laugh; or somebody just unexpectedly says something. In Flamenco more than any of Saura's other musical films it's the rapt, intense interaction of singers and dancers and rhythmically clapping participant observers shouting impulsive olé's that is the "story" and creates the magic. Because Saura has truly made magic, and perhaps best so when he dropped any sort of conventional story.

Iberia is in a similar style to some of Saura's purest musical films: no narration, no dialogue, only brief titles to indicate the type of song or the region, beginning with a pianist playing Albeniz's music and gradually moving to a series of dance sequences and a little singing. In flamenco music, the fundamental element is the unaccompanied voice, and that voice is the most unmistakable and unique contribution to world music. It relates to other songs in other ethnicities, but nothing quite equals its raw raucous unique ugly-beautiful cry that defies you to do anything but listen to it with the closest attention. Then comes the clapping and the foot stomping, and then the dancing, combined with the other elements. There is only one flamenco song in Iberia. If you love Saura's Flamenco, you'll want to see Iberia, but you'll be a bit disappointed. The style is there; some of the great voices and dancing and music are there. But Iberia's source and conception doom it to a lesser degree of power and make it a less rich and intense cultural experience.

SHOWTIMES

Fri, Apr 21 / 4:45 / PFA / IBER21P

Sun, Apr 23 / 3:45 / Castro / IBER23C

Tue, Apr 25 / 9:45 / Kabuki / IBER25K

Thu, Apr 27 / 2:45 / Kabuki / IBER27K

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2006 at 11:49 AM.

-

Tsai Ming-liang: Wayward Cloud (2005)

Love in a time of watermelons

Tsai is back with his alter ego, the pretty-boy punk, Lee Kang-sheng, who this time has stopped selling watches and become a small time porn actor (I guess). The girl who wanted him, Chen Shiang-chyi, is back too and this time, they get together in the end (sort of).

Avantgardist filmblogger Adam Balz writes," The Wayward Cloud, a film by Tsai Ming-liang, is a profound glimpse into the sheltered world of pornography." Actually, Tsai can't really be trying to represent pornography accurately. His "pornography" shooting scenes are monotonous rabbit-style hump jobs by Lee Kang-sheng with real Japanese porn actress Sumomo Yazakura. The whole film is very impressionistic and surreal. The "world of pornography" is "represented" by nothing but lengthy shots of the boy, the girl, a cameraman and a light man, none of whom talk.

Balz admiringly continues with a question that without him we might not have thought of asking: "Who else would open a movie with a lengthy shot of an empty parking ramp, only to shift to a woman clad in a nurse's uniform lying on a bed with a half-watermelon placed over her genitalia? That style of unabashed risk-taking is something we'll never find in mainstream Hollywood, not for a long time." Mainstream Hollywood will not be jealous of the accomplishment of a lengthy shot of an empty parking ramp. The lady with the watermelon is hardly a breakthrough either. Unabashed risk-taking? Tsai is simply setting a mood, or more accurately declaring that this is a Tsai film. But this beginning really might be the work of any pretentious film school student.

What is arresting and way beyond film school are the lip-synced musical sequences of a chorus of women brandishing pink umbrellas and Lee Kang-sheng gyrating jauntily and gamely (the actor is nothing if not game) in a yellow raincoat, and he in a public men's room costumed as a giant penis with the women's chorus this time wearing orange cones jutting from their breasts and singing a song which can be interpreted as referring to lost erections. These sequences are a mixture of the comical and the purely bizarre that is truly jaw-dropping and might be very effective if incorporated into a satirical story, but Tsai was never made to work this way. His method is to hint and suggest. These sequences are simply interludes that liven up a depressing set of other scenes about lost people in a big apartment building in a city that's so low on water in summertime that people are requested to switch to watermelon juice. Yes, the girl is the one who met the boy when he was selling watches. In fact very early on she actually asks him, after a long mute sequence where they just stare at each other wordlessly, "Do you still sell watches?" He gives her a look as if to say, "You must be kidding!" What he's doing of course is acting in porno movies. Or he's supposed to be. As I said, his rabbit-style hump jobs are unlikely to be usable in even the most rudimentary kind of real porno movie; it's just a sketched-in way of saying, "This guy is a porn actor now."

But what else is there? A final scene in which the porn actress is found by the girl in the elevator naked and seemingly passed out. Shiang-chyi drags her back to her apartment. It's a slow process, I can tell you. Eventually the porn filmmakers find her again, and decide that despite her apparently being unconscious or dead, she'll do to shoot another scene. So they drag Ms.Yazakura down to the other end of the hallway. That's a long process too. It was more fun sitting in the kitchen staring at nothing in What Time Is It There? or watching people watch a movie in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. If this film is so "audacious," why is it so often boring? The following sequence, which caused observers to walk out of the festival theater in sophisticated Berlin, and wherein the boy humps the corpse, or unconscious woman, while shot by the maniacal but wholly unsubtle filmmakers, watched by the girl through a large keyhole window right over the bed, till the boy has a big orgasm and gives it to the girl on the face, ends the movie.

Balz begins, "In the first chapter of his 1979 book Seduction, French semiologist Jean Baudrillard discerned the spheres of sex in relation to pornography: "Pornography is the quadraphonics of sex. It adds a third and fourth track to the sexual act. It is the hallucination of detail that rules. Science has already habituated us to this microscopics, this excess of the real in its microscopic detail, this voyeurism of exactitude." I guess that makes this a cool movie, for him. I'm afraid I found it a tremendous disappointment. The River was pretty and haunting in its desolate urban melancholy, and What Time Is It There? is a delicate depiction of loneliness and separation that playfully alludes to Truffaut. Tsai is playing around in Wayward Cloud in another sort of way, but it's one that this time comes dangerously close to complete solipsism. Rent a real musical or a real porno film, you'll be better off. Note: the French title of this film is "The Taste of Watermelon." But that's another story…

SHOWTIMES

Sun, Apr 23 / 9:30 / Castro / WAYW23C

Tue, Apr 25 / 10:15 / Kabuki / WAYW25K

Wed, Apr 26 / 3:30 / Kabuki / WAYW26K

Fri, Apr 28 / 9:15 / PFA / WAYW28P

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2006 at 12:03 PM.

-

Nobuhiro Suwa: Perfect Couple (2005)

Nobuhiro Suwa: A Perfect Couple (2005)

Oppressive boredom

A couple on the verge of divorce (they announce it to friends at dinner), Marie (Valéria Bruni-Tedeschi) and Nicolas (Bruno Todeschini) have returned to Paris after some years of living in Lisbon to attend an old friend's wedding. Although they bicker a lot, at the film's end there's a chance they aren't going to get divorced after all. The shift in locale has caused a change in feelings. Or is it just that the movie has no development?

The Japanese director Nobuhiro Suwa had French contacts several years ago when he worked with Béatrice Dalle and Caroline Champetier, his cinematographer again here (who in turn has worked with some of today's most illustrious French directors) on M/Other, an "experimental" remake of Resnais' Hiroshima Mon Amour, a film selected to be shown in the Un Certain Regard category at Cannes 2002. And Un Couple parfait owes something to improvisational directors like Cassavetes.

But if Cassavetes is the model, there is a difference, and an important one. Cassavetes worked with New York actors and settings that he knew well; Suwa, who speaks no French, just set things up and let things and the actors play out on their own -- in what he says was the shortest shoot he's ever done. Well, the crew got their jobs out of the way quickly, but it's a slow business to watch the results. There are moments of truth here generated by the leads, but overall, not enough to relieve the longueurs of this oppressive, stifling, and tedious study of a marriage. For the most part it doesn't look very good either. Astonishingly, considering her having worked with Garrel, Beauvois, Fontaine, Jacquot, Téchiné, and Desplechin on some very good films, Champetier's images are so murky in this unfortunate effort you can't even see Tedeschini most of the time.

Improvisation is a worthwhile, perhaps sometimes essential, way for actors to hone their skills, and can be a useful way to add emotional authenticity and realism to screen performances. There's no doubt that a whole film that's improvised is a challenge for the principals here that they were brave to have taken on, and Bruno-Tedeschi in particular achieves some truthful moments. But the technique is risky. Improvisational filmmaking quite often seems more fake than movies that are carefully choreographed. Under pressure and with no specific plan actors leave out necessary expository details. When they tell Esther (Nathalie Boutefeu) and Vincent (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing) they're getting divorced, Marie and Nicolas forget to mention why and we never learn. They go on about other people's children so there's a hint that they're dissatisfied not to have produced any. Marie accuses Nicolas of being a fake. Well, acting is faking. The trick is to make it real. When actors are improvising, using fragments of their own experience and personalities with no intervention from a written text, the result may appear raw and authentic but it may as easily seem vague and unfocused. The content can't be completely autobiographical on the part of the actors, but without a text something is therefore missing. The actors in A Perfect Couple don't work up enough steam or have the chops and chutzpah to make this succeed as Cassavetes' actors such as Peter Falk, Gina Rowlands, Ben Gazzara, Seymour Cassel, and Cassavetes himself could do because of their rapport with the director and their history together and because of interest-generating conflicts they and Cassavetes introduced into the film plots.

Nicolas has a flirty drink with another wedding guest, Natacha (Joanna Preiss), and Marie runs into a school friend named Patrick (Alex Descas) and his son (Emett Descas) at a museum. Both scenes hint at the possibility that the couple may want to explore other possibilities, but being improvised without supervision, they fail to interact effectively with the whole. All we know is that at the end there is still some warmth in the marriage. But it's hard to care, since we're learned so little about the couple. Not much can be said for the performances of Bruno-Tedeschi and Tedeschini, who seem to have little in common other than their rhyming names.

The dullness (or shall we say neutrality) of the proceedings is increased by long static shots, sometimes with no actors in view, and occasional inexplicable blackouts suggesting the digital camera ran out of juice. If these effects create a sense of something new or convince you you're not watching unsupervised actors wildly flailing about for ideas and are actually eavesdropping on "reality," then rush to see Un Couple parfait. Otherwise you may want to take my advice and stay away from this clinker and hope it doesn't get to run the festival rounds; it isn't going to be at a theater near you and that's a good thing.

SHOWTIMES

Fri, Apr 21 / 9:15 / PFA / PERF21P

Sun, Apr 23 / 12:30 / Kabuki / PERF23K

Tue, Apr 25 / 9:30 / Kabuki / PERF25K

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-09-2014 at 06:07 PM.

-

Fernando E. Solanas: The Dignity of the Nobodies (2005)

Fernando E. Solanas: The Dignity of the Nobodies (2005)

Chaotic and grainy, but for some of us, essential viewing

This tumultuous and boldly-titled documentary, La Dignidad de los nadies, focuses on the poor and dispossessed of Argentina and their recent increasingly successful battles against neo-liberalism and globalization, as well as the continuing severe problems with repossessed farms, enormous poverty, widespread joblessness, and a socialized health care system in chaos. Fernando Solanas, a man of the revolutionary Sixties, sprang to fame in his early thirties with his 1968 documentary trilogy La Hora de los Hornos/The Hour of the Furnaces, and other bright spots in his career include Los Hijos de Fierro/The sons of Fierro (1975), Tangos: El Exilio de Gardel/Tangos: Gardel's Exile (1985), Sur/South (1988), El Viaje/The Voyage (1992), and Memoria del Saqueo/A Social Genocide (2004), recipient of the Golden Bear at Berlin.

Solanas says he began shooting The Dignity of the Nobodies with a large digital Beta camera but people thought he was from TV and behaved unnaturally, so he switched to smaller cameras, "replacing the possibilities of a better image by greater truth." That is the tradeoff. This documentary is full of life and poverty and mud. There's no place it doesn't go. It is truly a film of the people. But the look of the small digital cameras is rough and grainy. Unfortunately, we suffer from a new technology in transition.

The Dignity of the Nobodies is part of a larger picture, beginning with the forced resignation of President de la Rúa followed by a succession of several other failed presidents, the default on the international debut, the detaching of the Argentine peso from the dollar, and the subsequent "sacking" or robbery of the nation that took place in 2002 when banks shut down, local debts were absorbed into the national dept in what might be called an outright explosion of corruption in democracy after the country got rid of its military dictatorship. This is the sequence of events described in Solanas' Memoria del Saqueo (Social Genocide is the English title but obviously the title more accurately rendered is "Memoir of a Sacking"). The Dignity of the Nobodies is hence described as "the second chapter in a series of four documentaries exposing the corporate sacking of Argentina" and said to be focused "on the victims and their struggle to fight back." The projected two sequels are to be called Argentina Latente/Latent Argentina and La Tierra Sublevada/The Roused Land.

The Dignity of the Nobodies, which ranges all over Argentina as far as Patagonia to tell its story, is presented as a series of specific portraits, or sketches of situations as seen through the experiences of individuals. Toba, for example is a teacher who runs a free food kitchen, and saved the life of Martin, a delivery man who was shot by police at a 2001 police riot against the mothers of Plaza de Mayo. Antonia and Chipi are two others who feed two hundred people at a soup kitchen. Margarita and Colinche are a homeless and jobless couple with nine children who do odd jobs from a horse drawn cart; Colinche's dream is for her children to go to school; and in the sequels presented at the film's end, they are going to school. The "picket camp" is a huge gathering of jobless who live in solidarity and block roads to make their plight known: these scenes resemble the US in the Depression era. Lucy is a farm widow who has led a fight of other farm wives to prevent auctioning off of farms in an ongoing series of group disruption actions during which they sing the national anthem at auctions and shut them down.

Darío is a charismatic young martyr of the poor people's struggle -- he looked rather like Che Guevara in his prime -- who died in another police riot when trying to save a friend. Darío's death and the protests of his girlfriend, Claudia, and a host of supporters led to the unmasking of the killers and their imprisonment. The penultimate story is of Gustavo, a young priest of Greater Buenos Aires who's so outspoken against police "maffias" (their spelling) and their collusion with local mayors with ties to the previous dictatorship that he is driven out of his church and subsequently gives up the priesthood to be a full-time activist. Again the people were able to find justice in a case of police murders. The last segment is about the Patagonian Zanon ceramics factory. Several thousand factories were shut down as a result of the economic collapse of the country. Workers have seized and reopened about 160 and the Zanon factory is one that has been restored to productivity and sells to the local market. Keeping such factories open is an ongoing struggle against authorities, as is the struggle to prevent farms from being repossessed, despite the success of Lucy's group. The film ends with a freeze-frame on the young pretty face of a girl student, because students now donate time to help out at the hospitals.

Solanas is a profound chronicler and polemicist, but the chaotic nature of his material perhaps robs him of the possibility of being an artist. One longs at times for some Olympian voice, some kind of explanation by a provocative muckraker like Michael Moore or lucid diagrams like those in The Corporation, or the detailed personal intimacy of a story like Benjamin Kahn's in his documentary of searching out the identity of his father, the great architect Louis Kahn, in My Architect, or the almost clinical and yet sweet and human poetry too of a microscopic study like the one of schoolchildren in the French To Be and To Have, or the searching analysis and commitment of a biographical study like Herzog's Grizzly Man. Solanas can't provide any of these qualities. What he can provide in abundance is essential raw information and a rich human document. His movie may lead some of us to go and find out more about what has been happening in Argentina over the past decade. Despite the chaotic and unwieldy material, the editor Juan Carlos Macias bravely molds things into a coherent flow -- even if one inevitably knows this is only part of a larger picture requiring the kind of analysis provided in the preceding Solanas film, Social Genocide. Highly recommended for anyone interested in political documentary and essential viewing for students of contemporary Latin America. For all its graininess, great stuff; and about as humanistic and social-consciousness-raising as documentary filmmaking can get.

SHOWTIMES

Wed, Apr 26 / 6:00 / Kabuki / DIGN26K

Thu, Apr 27 / 8:30 / Kabuki / DIGN27K

Sat, Apr 29 / 1:00 / PFA / DIGN29P

Mon, May 01 / 7:00 / Aquarius / DIGN01A

Column on The Dignity of the Nobodies by local online writer Michael Guillen on his blogspot The EveningClass

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2006 at 11:44 AM.

-

John Longley: Iraq in Fragments (2005)

Sad images that don't quite add up

Longley's visually beautiful and emotionally saddening film in three parts, shot during two years spent in Iraq between the immediate aftermath of the invasion in 2003 and 2005, arouses tremendous hopes but ends by quite dashing them. Longley is great with a camera and patient with children and his documentary is full of lovely, yellow-filtered images. But his project to describe post-invasion Iraq is both over-ambitious and reductive. Longley wants to cover what he thinks are the three main divisions of the country -- Sunni, Shiite, and Kurd. But he tries to do this by reducing his focus to children and old people, speeches, and a few scenes of public violence, and the result feels empty.

Most memorable, because most integrated and most eloquently narrated (by the wispy, childish voice of the boy himself), is the first segment about eleven-year-old fatherless Mohammad (his father disappeared after speaking up about Saddam at some time in the past), who lives and works in the Sheikh Omar district of Baghdad. The camera is close up on Mohammad's sweet, expressive young face; or his voiceover declares, "Baghdad used to be beautiful" over shots of the city before the invasion (Longley made a short visit in 2002) and then, "the world is so scary now" as we watch big brown helicopters sputter threateningly overhead.

Mohammad lives with -- his grandmother, is it? We never see her or see him at home; but Longley hung out at the little auto repair shop where Mohammad was working long enough to fade into the tool racks and, astonishingly, to film uninterrupted Mohammad's encounters with his sometimes affectionate but more often abusive boss -- who smacks him and calls him a son of a whore for playing marbles with other boys; for not knowing how to spell his father's name; and finally for even spending time at school, which he is forced to give up to keep the job.

The boss also speechifies a bit about the occupation, which he considers far inferior to the days of Saddam: we can't help seeing this fat bully as a little Saddam lingering on in the Sheikh Omar district. Other voices are cut in throughout the segment with Baghdadis, presumably Sunnis (since that's meant to be the focus of this section), declaring the same things: the Americans just came to set up a military base, they're here for the oil (Mohammad says that too), they have not brought democracy, it's even worse now than under Saddam, everything they say is a lie.

Desperate for a father, Mohammad murmurs repeatedly that his boss loves him but in the end admits he has to escape the abuse. The rationalizing over, he leaves to work at his uncle's larger shop. He may still have his dreams of becoming a pilot and flying to more beautiful countries. Earlier, we watched him at school looking bright and eager as the teacher drilled the children on "dar" (house) and "dur" (houses) and quizzed them on how to use these words.

Did Mohammad get to go back to school and learn how to write "Haithem" (his father's name)? That we don't learn. Nor do we see his new workplace, or hear from relatives. Why did Longley focus so much time and attention on this boy? There's something heartrending about his little story, but he can't be seen as the future of the country. Alas, he has little future. This picture of Baghdad is vivid, but too limited.

Parts Two and Three focus, respectively, on Moqtada Sadr, Najf, and the movement to empower the Shiite majority and bring religious rule to the country; and on a sheep-herding and brick-making family in Kurdistan. Longley and his interpreter Nadeem gained remarkable access to the Moqtada camp through one of his men, thirty-two-year-old Sheikh Aws al-Kafaji, who let them film his activities, strategy meetings, rallies, marches, speeches, religious ceremonies, and an alcohol raid on the local market. There's even footage of a hospital, with a wounded man on a stretcher yelling, "Is this democracy?" "Amrika 'adu Allah," someone declares -- America is the enemy of God. Most noteworthy is footage of Sadr's men (or Kafaji's?) roughing up random people in the market suspected of selling booze and of encounters of Sadr's men with Spanish troops around the Imam Ali Shrine. The rest is a chaos of images, vivid and intense enough, but -- despite clear translations in subtitles of all the speechifying and excerpts from committee meetings -- without any sense of what it all may mean. No doubt about the fact that a lot of this material was dangerous to shoot, and again, Longley's camerawork is superior; this section will serve as excellent stock footage for future historical documentaries of the period.

Things became so dangerous that by September 2004, Longley decided to go north -- Koretan, south of Erbil, a small community of farms and brick ovens. From here on, no more Arabic is spoken, only the Kurdish language. After all the tumult of the Shiite uprising, Longley reverts to a smaller canvas, again focusing on boys, two close friends this time, so intimate they walk hand in hand to school, and their fathers. Mostly we see one of the boys, "Sulei" (Suleiman), an unsmiling youth with a chiseled face who wants to be a doctor, and his aging, bespectacled, chain-smoking father, a shepherd. Sulei talks about struggling to study his hardest to go into medicine, but again, the demands of supporting his aging dad and working both at baking bricks and tending sheep force Sulei to drop out of school -- even sadder than the case of Mohammad in Baghdad, because Sulei had a real desire to be somebody. The picture is the opposite here. Someone mentions Saddam's massacre of Kurds in the Eighties and moving in of Arabs, and the old man says, "God brought America to the Kurds." Quite a contrast to "America is the enemy of God." But again, a lonely boy without a future is no picture of the Kurds or of this complex land.

SHOWTIMES

Wed, Apr 26 / 6:15 / Kabuki / IRAQ26K

Fri, Apr 28 / 9:00 / Kabuki / IRAQ28K

Thu, May 04 / 8:45 / PFA / IRAQ04P

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-25-2014 at 11:26 PM.

-

Samir Nasr: Seeds of Doubt (Folgeschäden, 2004)

A measured story of erupting prejudice

Director Samir Nasr is German on his mother's side and Egyptian on his father's side. This protagonists in this feature (though scripted by German Florian Hanig) could be his parents. Tarik Slimani (Mehdi Nebbou) is an Algerian-born biologist researching the Ebola virus who lives in Hamburg with his blonde German wife Maya (Silke Bedenbender) and their little son, Karim (Mahmoud Alame). Not devout himself, Tarik is nonetheless raising Karim as a Moslem, and Karim's the only one in school not attending bible class.

Events get rough for Tarik and his little family due to post-9/11 anxieties. Nasr's story, which he reshaped to fit his own ideas working with a plot proposed to him by Arte television, isn't so much a political thriller (as originally planned) as it is a study of how stereotyping and cultural ignorance almost wreck a marriage when legitimate suspicions mix with hysteria because of the way Arabs and terrorism have become identified in the West. The fact that Hamburg is where the main European al-Qaeda cell was located turns up the volume on things.

At a dinner given by Maya's boss (she's the art director of an ad firm), their host says something about the Moslems still being in the Middle Ages. Tarik says he's glad there are so many experts on Islam now. The boss answers that he's no expert, but after 9/11 he read the Koran -- very carefully. Well, Tarik ironically responds, then 9/11 had some positive effects.

A report of this conversation may be why the German feds' terrorism branch starts talking to Maya shortly thereafter; we don't know the exact reason. But we do learn Tarik went to a big Moslem wedding in town attended by one of the 9/11 bombers, and without telling Maya.

In this conventionally well-made and well-acted film what emerges as important isn't isn't so much that the feds are on Tarik's tail, but that if you've got an Arab working with Ebola plus 9/11 that equals suspicious cops. The result is inevitable.

Maya is angry at being approached and takes Tarik's side, insisting the suspicions are preposterous. But little by little her faith in her husband is gradually eroded when other things happen: a pious Moslem Iranian friend comes and stays with them, without her having been told ahead of time, to attend another big Moslem wedding; without warning there's a large withdrawal from their bank account sent out of the country; as she discovers only later some of the Ebola in Tarik's lab mysteriously disappears and Tarik is banned from the lab; finally Tarik goes to Paris for the day on the very day when a terrorist attack occurs there, and he doesn't tell her about this trip either. She only learns of it by discovering the ticket among some papers in the flat. The Iranian friend may be the most suspicious element, unless you suspect Tarik of stealing Ebola out of his own lab. Or perhaps it's all equally suspicious. The friend is a devout Moslem and very dedicated: he runs a rural health clinic where he's pretty much on his own. (Could he really be training terrorists?) Meanwhile Karim gets into trouble at school by fighting with his best friend over religion; Tarik backs him up a bit on this, and Maya is annoyed by the way he does that -- but by then her trust is eroded.

There is a multiplication of detail, but nothing is proved to incriminate Tarik. This excess of vaguely, possibly incriminating detail is needed to justify Maya's loss of faith in her husband which climaxes when she runs to the federal police terrorism office chief who's seen her and asks about the attack in Paris. She rushes home from that and wrecks the living room, throwing papers in every direction and finally coming across the plane ticket.

Interpreters of the movie feel we're successfully duped into thinking like Maya and hence are surprised at the end when we learn Tarik was innocent -- that the Ebola disappearance has turned out not to be his fault, that he's back at the lab, and that his trip to Paris was for legitimate professional reasons. Not being a latent profiler of Arabs, however, I wasn't successfully duped by any of this. I was in Tarik's corner; observed how the excellent Mehdi Nebbou consistently projects reason and decency; and never for a minute believed Maya's suspicions justified. I can only say that Nasr and writer Hanig are a little bit guilty of profiling Maya as a "typical" non-Arab, innately suspicious, just waiting for her prejudice to be drawn out.

Since this slick, glossy movie was made for Arte TV, I thought of the British Traffik miniseries and the English wife who, when her German husband's revealed to be a drug shipper, far from turning against him as Maya does, jumps in and takes over the business.

But what's good about Seeds of Doubt is that in its conventional, smooth style it makes the escalating stress of Tarik and suspicion of Maya and the trouble Karim has at school unfold with a sense of cumulative inevitability that is psychologically convincing even though the plot is a little contrived. This is the portrait of a marriage in which communication has been, and under stress continues to be, awfully poor. But there are such marriages, if they're not always healed as easily as this one is.

One wishes the US were anywhere near such a level of sophistication about this hot topic, but can you imagine a US film this measured about an Arab with an American wife, post-9/11? And can you imagine an Arab movie director given the kind of opportunities and recognition in the US that Samir Nasr has been granted in Germany?

SHOWTIMES

Thu, Apr 27 / 6:15 / Kabuki / SEED27K

Wed, May 03 / 4:30 / Kabuki / SEED03K