-

Andrew Bujalski: COMPUUTER CHESS (2013)

ANDREW BUJALSKI: COMPUTER CHESS (2013)

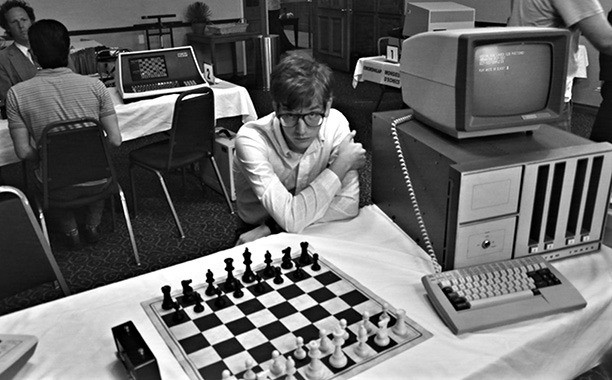

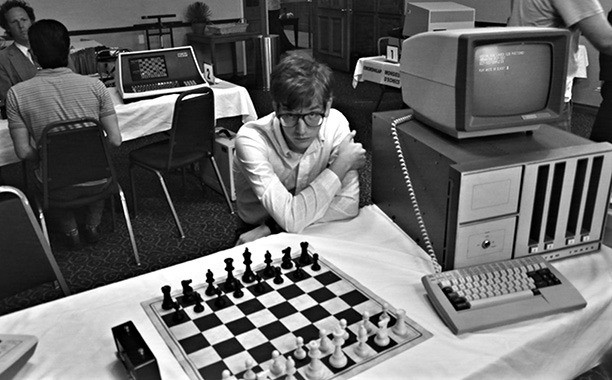

PATRICK RIESTER IN COMPUTER CHESS

Terrifyingly nerdy

Mumblecore "godfather" Andrew Bujalski (Mutual Appreciation, Funny Ha Ha, Beeswax) takes a new tack in his latest film, Computer Chess, away from his own generation and time into a moment that might seem for him resonantly, awesomely prehistoric. He reconstructs (or invents?) a weekend circa 1980 computer chess convention long before the sleek age of smart phones and Mac Airs. To do this he uses a combination of improvisation, studiously bad hair and unfashionable clothes, and ancient Portapak videotape equipment, mimicking the shooting style that goes with this technology, thus recapturing in the round a scary nerdiness. The result can seem brilliant -- or totally stupid, depending how you look at it. The cult potential of this film is unquestionable. It is instantly recognizable as unique. It may not initially be a whole lot of fun to watch -- unless, that is, you're consciously filtering it through Pynchon and comparing it favorably with Pablo Larraín and and Harmony Korine, which not all viewers will manage. Distinctly odd this certainly is, one of the year's most original American films; and conceivably a bold new step for Bujalski to greater scope and a wider audience.

But this is a movie that will polarize audiences. When it showed at Sundance "squares" like Hollywood Reporter's Todd McCarthy ("deadly dull") and Variety's Justin Chang ("Hit or miss") dutifully noted the singularity and authentic look of the film but didn't particularly like it. "Hipsters" like Mike D'Angelo ("78/100, "Deeply, deeply, deeply weird"--it's now no. 2 on D'Angelo's year's running ten-best list) and Vadim Rizov ("major filmmaking") on the other hand were thrilled to the core. (These were January, pre-release, reviews.)

As so often the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Both sides acknowledge the spot-on evocation of period (even though that period's a bit vague). The consciousness-raising est-like meetings (with a dash of group sex) also happening at the dinky hotel that weekend could be well before 1980 and Spotpak cameras go back to 1969. The bad hair and clothes and sexism evoke something like thirty years ago well, as does the fuzzy black and white video (Bujalski's ironic response to chiding about when he would move to -- modern -- video from 16mm. film).

But authenticity and bad acting are not the same: they may come close, but they will never meet. It's also true that the humor here falls flat, and if this isn't a comedy what is it? Computer Chess is original but also a long slog whose cringe-worthiness peaks when the middle-aged couple try to lure the shyest, youngest programmer Peter Bishton (Patrick Riester) into sex with them. The pervasive nerdiness has a terrifying way of making you feel it's entering you and becoming you and reflecting everyday life more than any other movies do.

And there is the meta-fictional realization that all this "realism" is highly stylized. In fact what's lacking are the one or two cool guys who'd set off the gang of nerds and make them nerdier, as a drop of black paint is said to make a gallon of white paint whiter. But everybody thinks this seems like real found footage. It does -- sort of. And one does appreciate what the Guardian writer Andrew Pulver admiringly noted, "a wide-eyed appreciation for just what humble, shabby beginnings the digital revolution sprang from."

Real computer programmers and various personalities participate as cast members in Bujalski's geek game along with huge clunky period computers with clackity keyboards and black screens spewing rows of white digits. They are outsized -- but still not capable yet by a long sight of beating a living human chess master. As A.O. Scott notes, "the triumph of I.B.M.’s Big Blue seems a very long way off." The program of the event is to pit various rival computer chess programs against each other in playoffs, and at the end the winning program gets to play against a human, the arrogant conference leader Henderson (played by academic and film critic Gerald Peary). Some programming team heads like the experimental psychologist Martin Beuscher (Wiley Wiggins) coyly vaunt their personal aims and methods. Others, like Shelly Flintic (Robin Schwartz), repeatedly touted as the tourney’s first female participant, or the shy and possibly brilliant youngster Peter, hover mutely in the background. The boastful and evidently disliked Michael Papageorge (Myles Paige) is for no good reason forced to wander the hotel at night searching for a room. A skinny call girl hovers in front. In a mystical sci-fi touch, Peter thinks the computers have souls and the one he's involved with is failing because it doesn't want to play against another computer but against a human. The goofy, invasive free love encounter group conference, led by a tall black "African" Papageorge thinks may just be from Detroit, is an obvious contrast, and helps round out the sense of period goofiness. The plump lady who tries to seduce Peter says he'll never reach his "true potential" if he sticks to programming or the 64 squares of a chess board -- and so on.

Sudden split screens interrupt the otherwise period video images, which as has been pointed out are more consistently dated in visual style than the use of Sony U-matic cassette video cameras in Pablo Larraín's No. For a few minutes in an unrelated scene of Papageorge at his mother's, Bujalski reverts to blotchy color film. If you have seen the documentaries about the human-computer chess wars (notably Kasparov vs. Deep Blue) you will miss here any depth or excitement in the snatches of games that, as Todd McCarthy wrote, "are excerpted in ways that offer no insight or, God forbid, tension." In fact Bujalski's deadpan humor here bets on deliberately letting everything fall flat. That's the point.

There is much to ponder here, perhaps most resonant being the idea of a crowd of geeks and nerds who don't yet know they are to rule the world and of a burgeoning technology that now looks ridiculously primitive, reminding us how ruthless progress is and how clunky and limited present technology is likely to look thirty years hence.

Now that the film has had its July US theatrical release and will get more widely reviewed, awareness of it is likely to spread; and it has had time to percolate in my mind as something memorably unique. They don't make 'em like this any more (if they ever did). A.O. Scott of the NY Times describes Computer Chess as "sneakily brilliant" and ends, "Artificial intelligence remains an intoxicating theory and a heady possibility, about which I am hardly qualified to speak. But I do know real filmmaking intelligence when I see it." Aaron Hills of the Village Voice calls the film "So far the funniest, headiest, most playfully eccentric American indie of the year." In five months or so he may want to drop the "so far."

Computer Chess debuted at Sundance (surprisingly, a first for Bujalski), in its "Next" section. It was also shown at Berlin, Montclair, the SFIFF (the latter where it was originally screened by me). US theatrical release (at Film Forum, New York) was July 17, 2013.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2015 at 12:30 AM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks