-

New York Film Festival 2020

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-28-2021 at 07:01 PM.

-

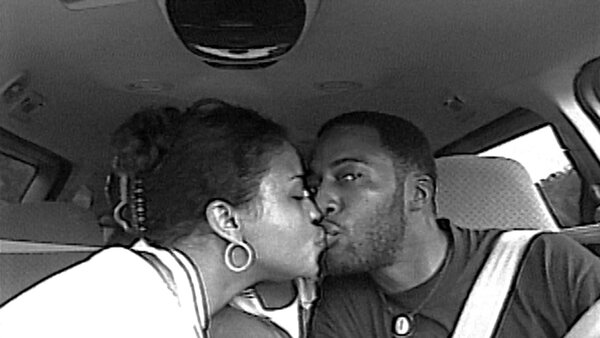

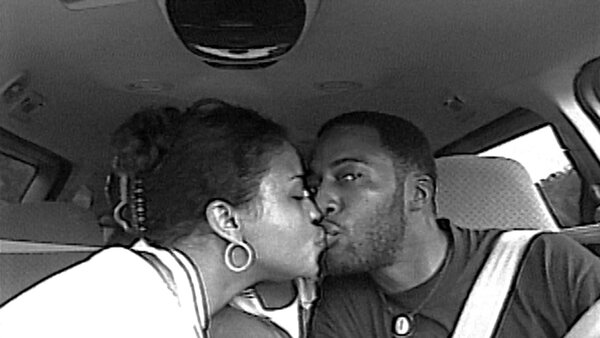

LOVER'S POINT (Steve McQueen 2020)

STEVE MCQUEEN: LOVER'S ROCK (2020)

A celebration staged - then watched

Lovers Rock, the opening night film of the 58th New York Film Festival, is an hour-plus television series episode that is part of McQueen's five-part "Small Axe" anthology that premieres on BBC One later this year and in the US on Amazon Prime.

Lovers Rock is nearly zero as a story - boy meets girl, they dance all night, take dawn bike ride, girl sneaks into house in time to go to church - but as a staged event it is enormous, a West Indian soul-reggae house party dance night that Peter Bradshaw, who gives it five out of five stars in a Guardian review, calls "the best party ever." He accurately says "everything and nothing" happens and notes most of this 68-minute film, co-scripted by McQueen with writer-musician Courttia Newland, designed by Helen Scott and (mainly?) shot by Shabier Kirchner, would be a five-minute sequence in a regular film. Dennis Lim, the Film at Lincoln Center Program Director, in a Zoom-style interview with McQueen, suggests this is more like one of the short art films he made before he got started on features, the chronicling of a process-event. I came to scoff (not a fan of McQueen coming into it), but I became a convert. This is a rich, lush, enveloping event. It's alive. It's young sexy blackness as you've never seen it caught on film.

But Bradshaw is also right in calling it a "novella," because it has characters and mini-backstories to burn ("everything") - only they're brief and sketchy ("nothing"). McQueen told Lim this remarkably rich "staged" event was (became) a real party; it would have happened (gone on, and on and on) whether the camera was there or not; he felt "invited," and (he said this two or three times) "it was euphoric." In a way all but Michael Ward and Franklyn and Amarah-Jae St Augin as Martha, the couple the camera follows out into the night-into-morning at the end, are extras. but they are extras who are stars in their own right, starring in their own movie, living their own party, and they give their all. McQueen just had to "know when to step back" - and watch and let it happen. Self-indulgent? Yes, but no, because he frames it so beautifully.

The time is 1980. The setting is set in Ladbroke Grove, west London, over a single evening at a house party in 1980. The people are mostly West Indian first or second generation men and women. Blacks weren't really welcome at London dance clubs, which had quotas for them, and so they made their own so-it-yourself clubs, for themselves. They took a living room, filled it with a humongous set of speakers, and charged a 50p entry fee at the door, extra for food and drink from the kitchen. Men dressed up in tight bell bottoms and fancy dress jackets with eventful hats; women wore fancy, slinky dresses they or their own had made for them. McQueen, who calls this a "blues party," is drawing on the experience of his own parents here, and a female relative whose father left the door open so she could sneak back in after a dance party in the morning, just as Martha (St Aubin) does here, to deceive her religious mother and go to church with her Sunday morning. All this is there, starting with the dragging in of the speakers and setting up of the table to play the vinyl, and dragging of the sofas into the back yard for private, more romantic interludes by couples during the night.

The music is enveloping. The atmosphere is sexy, and sexier as the night wears on. The music is lover’s rock, soul and reggae. Lovers rock is a thing, a "largely underground phenomenon," London black reggae emphasizing women's feelings, a genre that went global, a Guardian article Bradshaw references explains, but went largely unrecognized at home and faded away.

I don't know how period-authentic all the gestures are, but McQueen says they avoid gestures that aren't. One is the way the men grab the women's elbow, then slide it down to their hand, asking for a dance. Did men drink bottled beer while dancing? I guess they did. They light a lot of nice long thin spliffs, and the women smoke cigarettes, innocent highs. It seemed like some of the men were very predatory, but it's interesting how they cloak it in an air of chivalry and flowery compliments. Martha comes in with her friend Patty (Shaniqua Okwok), who disappears early on. Martha runs out after her but can't find her, and, with a group of whit men aproaching her, quickly withdraws back into the party room. Apparently Patty is miffed that Franklyn has settled on Martha and not her. Or she didn't get the man she longed for.

At one point there's a moment in a bedroom with two women sitting on a bed kissing.

A remarkable and lovely moment comes - though in conventional terms, like everything else, it goes on too long, when the music stops and the entire crowd sings the Janet Kay song "Silly Games," a cappella. It's the kind of thing you'd absolutely insist had to be staged, and it apparently wasn't. McQueen says this just happened, he had nothing do do with it. It's climactic, but there's much, much more. Remember in Aleksandr Sokurov's Russian Ark part of the show-offy single take is the ballroom full of elegant costumed dancers with the Mariinsky Orchestra with Valery Gergiev conducting, and at the end the camera comes back to them, and they're still dancing? You imagine those dancers, dancing hour after hour for the camera. This is like that, only the dancers are having a hell of a good time. And at the end the music gets faster, and they get crazy, and the screen is full of figures jumping and jiving, leaping and down on the floor waggling their arms and legs.

Before she goes home Franklyn takes Martha to the garage where he works, to make out, to entertainher in privacy. But his young white boss comes in, all unexpected, because it's Sunday morning, and chews him out and says, "You don't bring your Doris here!" At this point, Franklyn drops his Jamaican lilt he's bee speaking in all night and talks to the young white guy in more "multicultural London," a bland of cockney. Was the Jamaican a fake? No, it was probably his first language. This is only a hint of the depth and richness of this remarkable film's cultural and social detail. As I said I cam to scoff, and I admit I did feel bored in the middle of it, feeling it was going on much, much too long, which it does by normal standards. But I was swept away in the deep soul vibe and, the warm eroticism, and the fantastic go-for-broke in-character lived performances of the ensemble. As an opening night film, in a real not virtual NYFF, this would have worked unusually well. It's engaging, energetic, upbeat, and unique. How great it would have been on the Walter Reade Theater's great sound system and big screen.

Lovers Rock, 68 mins., episode of McQueen's five-part "Small Axe" anthology series for BBC (two othes also included in the NYFF) watched in virtual form as part of the New York Film Festival, for which it was the Opening Night film.

MICHAEL WARD AND AMARAH-JAE ST AUBYN IIN LOVERS ROCK

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-18-2020 at 01:09 AM.

-

Malmkrog (Cristi Puiu 2020)

CRISTI PUIU: MALMKROG (2020)

MARINA PALLI AND DIANA SAKALAUSKAITÉ in MALMKROG

Idle rich with a lot to talk about, c. 1900

I reviewed Cristi Puiu's The Death of Mr. Laaarescu as part of the 43rd New York Film Festival in 2005. It was my first press screening at my first NYFF. It's also credited with spearheading a "Romanian New Wave." Malmkrog is named for a luxurious estate in Transylvania where the action, if we can call it that, transpires. Five Russian aristocrats in 1900, speaking to each other in stilted French as was their custom, talk from before lunch till after dinner about a variety of general subjects drawn from a book by the Russian 19th-century philosopher Vladimir Solovyov called Three Conversations. A 1915 English version is headed "War and Christianity from the Russian Point of view." It all goes to show the idleness of Russian aristocrats as seen by a latter-day Romanian, and mind-sets in which liberalism is a mask for colonialism and racism. It is largely a sterile exercise, more stagnant pond than New Wave, but the beautiful staging and disciplined acting are wonders to behold.

Stilted French - that is a determining factor. This doesn't have the quality of speech. There are two men - one man, a general, having left early - and three women. Besides war, the place of Russia in Europe and the world is another topic, and the existence of evil in the world a third big one. There are some characteristics attached to the speakers. For instance, it's the general's wife, Ingrida (Diana Sakalauskaité), who defends war. The letter she reads about her husband's satisfaction at killing a horde of Ottoman Bashi-bazouk soldiers as punishment for their hideous massacre of a town full of Armenians is one of the film's more memorable moments. The "Franco-Russian" Edouard (Ugo Broussot, a theatrically-trained French actor), understood to be a prosperous businessman, expounds at length (several prominent reviews, Jonathan Romney's for Screen Daily and Boyd van Hoeij's for Hollywood Reporter, refer to it as "mansplaining") on Russia's role as a "European" civilizer of the world, in a way that incorporates Solovyov's racist attitude to the "yellow-faced" Chinese. Two other women, Madeleine (Agathe Bosch), a dryly intellectual middle-aged woman and Olga (Marina Palii), young and condescended to but presumably Nikolai's wife, complete the endlessly chattering group. The actors' discipline and stamina are world-class.

Why is all this relevant, and what makes three hours and twenty minutes of stilted philosophical debate material for a film? The answer isn't evident, and this is a step backward, or further backward, from the lively, humane Cristi Puiu who made Mr. Lazarescu. This is more a test for film buffs and particularly festival-goers who pride themselves on their stamina and Olympic-level attention spans. It's like sitting through a Wagner opera if you're not a Wagner fan, but without the beautiful music. One reviewer recommended coffee "or something stronger."

There are moments of hints of excitement. We see in his own shortest of the five chapters headed "István," headed for the butler, who directs a team of nearly silent and diligent servants the outwardly "liberal" five conversationalists studiously ignore, that he hits a kitchen employee guilty of making bad - or could it be lightly poisoned? - tea. Later, there's a disturbance and loud music heard and the bell of the host Nikolai (Frédéric Schulz-Richard) is not answered. Then there is a wild chase of figures from the kitchen and explosions, with the five dropping to the floor. I thought revolution had come, and they had died. But we see them in the distance later out in front of the estate, mysteriously congregating. Maybe it was only firecrackers - after all, this was Christmas Eve. The sounds in the background, perhaps including a music lesson for a child, and the work of the servants, including the bathing and dressing and bedding of a member of the group who is unwell, show Puiu's meticulous attention to every detail, including of course furnishings and costumes. But one detail that has eluded him: making this action interesting or relevant to us.

"A pristine, sometimes terrifying vision, of the shimmering violence beneath the colonialist's veneer of politesse" says a current NYFF tag for this film. Nice one. But you can't sell this dry summary of a dated book that facilely.

Malmkrog, 200mins., debuted at the Berlinale FEb. 2020; Belgrade, Vilnius (internet), Cluj, and was screened online for this review as part of the New York Film Festival (Sept. 17-Oct. 11), hybrid with virtual and drive-in screenings.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-28-2021 at 07:19 PM.

-

GUNDA (Victor Kossakovsky 2020)

VICTOR KOSSAKOVSKY: GUNDA (2020

GUNDA WITH PIGLET IN GUNDA

In a pig's eye

What is the average life span of a pig? Well, that's just one of the many questions that Gunda, a non-fiction film focused on a large sow that's just given birth, will not answer for you. I confess myself resistant sometimes to the purely observational approach to documentaries, in dealing with subject matter where I'm ignorant of and could use some instruction. I am not a barnyard person. One of my thoughts while watching Gunda was though we get to hear the (enhanced) sounds, we don't have to smell the smells. I was grateful documentary Smell-o-Vision has not come, however John Waters might delight in the thought.

There is evidently a runt of the litter - isn't there always? But while the camera seemed to follow this less energetic, more tentative piglet, it was never clear what was going to happen to it, if the eponymous large sow would be helping it, or just testing it. Earlier on, she appeared to sit on a weakling. Here an explanation would have been welcome.

Of course, if there were explanations, this would not be the festival-ready art film it is, with its brilliant, contrasty black and white images, and its impressively austere aesthetic, it's willingness to take long pauses, when we're waiting for the piglets to come out of the hutch occupied by their mom, or for the free range chickens in another location edited in between the pig sequences, whose movements onto grassy surfaces are a marvel of tentativeness. For a bit, the film seems to have become a highly specialized closeup portrait of how chickens plant their - what do you call them? paws, claws, feet on the ground. And then comes the promised sight of the one-legged chicken. Yes, and a fascinating show of coping under adversity it is. And then the camera, as restless as the growing piglets, who grow jumpier and pushier in each successive sequence, moves on. What is the fate of the one-legged chicken? Did it live happily ever after? Another unanswered question.

But this illustrates that this film - which also cheats in shooting not just on Gunda's farm in Norway, but also on ones in Spain and Britain, and making them blend together - isn't simply observational, like, for example one of my longtime favorites and models of such filmmaking, Philibert's To Be and to Have. Because Kossakovsky, known for the "visionary" quality of his films, and their "simplicity," has chosen dramatic moments - a very large sow with a new brood; a chicken with one leg. Because observing these farm animals in their ordinary daily rounds would be pretty unexciting, unless presented in an informational documentary, filmed over a long period, with narration based on lengthy informed observation and expertise. Some things don't necessarily cry out to be made into an art film.

Nonetheless for many viewers no doubt Gunda does perform an important function. It takes you into an at least apparently unmediated view of the world of pigs and chicks, and cattle too (they like to stare at you, and use each other's tails as fly-whisks, while pigs get away from bugs by wallowing in mud). Away from the music and the narration, viewers may look harder, feel closer, and learn to form their own opinions. They will be uninformed opinions, but they won't be crafted by artificial anthropomorphic storylines. Of course we are grateful for a film that's so keenly observed and beautiful, and for the lack of a narration that might have been tasteless or corny. And needless to say, I was glad to have no dialogue after the tedious yakfest that was Crisi Puiu's Malmkrog, seen and reviewed here last night.

No dialogue is necessary for the stunning finale, when Gunda suddenly has her whole brood taken away, and the last ten minutes are her looking for them, and I guess going through the first stage of Kübler-Ross's five stages of grief. Executive-produced by now famous vegan Joaquin Phoenix, this brilliantly made film is a strong statement of the stark inequality of the place of humans in the natural world.

Gunda,93 mins., debuted at the Berlinale Feb. 2020, released theatrically in Norway Aug. 2020, and was part of the Main Slate of the New York Film Festival (Sept. 17-Oct. 11, showing Sept. 19, screened virtually as part of the NYFF for this review. A Neon release. Slated for Crested Butte and Hamptons showings in October.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 06-13-2021 at 06:16 PM.

-

THE CALMING 平静 (Song Fang 2020)

SONG FANG: THE CALMING 平静 (2020)

QI XI IN THE CALMING

Where life, though joyless, still is calm

I reviewed Son Fang's first film, Memories Look at Me, as part of the 2012 NYFF.

This one, about movie lady Lin Tong (Qi Xi), a documentary filmmaker who's broken up with her boyfriend Guiren, is itself in a sense becalmed. Call it meditative, observational, or, to be more trendy, slow cinema. In Japan for movie business, Lin only tells one Japanese guy what's happened. In Tokyo her hotel view at night is gorgeous. She goes to Niigata to see snow, staying in hotels, taking public transportation, alone. She looks at things. We get the point: she's lonely, perhaps shut down. Back in China, she moves into a new apartment. Visiting with her parents, her father, a doctor, is very ill now. They don't know. She doesn't tell them. She gives him congee. That's not much for forty minutes, but it's a kind of warmup, warmup for contemplation. I started to miss the pigs in Gunda. They're so enthusiastic! Even if they only grunt or oink. But of course it's just a question of tuning in. The Letterboxd responses are very happy and approving.

When Lin meets up with her good friend in Hong Kong, the energy level rises. She has a nice caucasian husband who speaks Chinese, which one rarely sees in a film. Asked about Guiren, she says things are as usual, but "Let's change the subject." Gradually one realizes Lin is not so much sad as learning to live alone. But as a kind of artist, she is used to that state. I remembered T.S. Eliot's The Cocktain Party, how Peter and Celia bond because they discover both like to "go to concerts alone, and to look at pictures." It's nice to experience certain things, like music and pictures, even wild nature, alone, but nicer if one can do that by choice, if one has a partner.

Lin is reminded she hasn't one. There's the nice husband, and another man who's just getting married, and the old couple observed walking, still in good health and still walking hand in hand. And Lin's own parents, but with the hint of loss in her good friend's grandmother's recent peaceful passing in her sleep.

To see how Lin is learning to experience things alone and to be, perforce, alone, we often see her against the window of a single hotel room, or on a train, or a boat ride, with the scenery behind her and no one nearby. Or lovely foliage, with no one else around. Every time the shot is beautifully composed, and that expresses calm. Aesthetics are a discipline that calms. "After great pain a formal feeling comes."

After many beautiful scenes experienced by Lin alone, she has pain, and spends time, unexplained, in a hospital. Then she attends a concert playing Handel's "Alexander Balus" oratorio, and hears the beautiful aria containing the lines, "Where life, though joyless, still is calm,/And sweet content is sorrow's balm." Life, though joyless, still is calm. That sums it up. "Sublime, don't you think?" as asks the Chevalier Danceny (Keanu Reeves) in Stephen Frears' Dangerous Liaisons, after music like this. A tear drips down from Lin's eye as she listens, as it should.

The Calming is very beautiful, and calm, so beautiful and calm it's not quite real and can't quite breathe. But it can provide great satisfaction to some viewers. If one had a copy, one could take a hit off it at almost any point, and zone out.

The Calming 平静 ("Calm"), 92 mins., debuted at the Berlinale Feb. 2020, and showed at the NYFF virtual festival Sept. 19. Screened online for this review as part of the New York Film Festival (Sept. 17- Oct. 11, 2020).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-11-2020 at 09:55 AM.

-

TIME (Garrett Bradley 2020)

GARRETT BRADLEY: TIME (2020)

A woman waits eighteen years for her husband to get out of prison

Time by documentarian Garrett Bradley is an amalgam. Focused on a black mother whose husband is in prison for nearly twenty years and her six sons, it blends a mixture of film footage. The most plangent and vivid, sometimes clumsy, is home footage shot by the mother herself of the boys for her husband. The rest was made by the filmmaker's cameramen of the family. The whole is joined together by conversion of all to black and white. The period footage is purposely jumbled up in time, to be not just documentation but the haunting of memory. The result is perhaps intentionally disorienting - a "vibrant cubist portrait," as Shri Linden puts it in her Hollywood Reporter review.

Sibyl Fox Richardson, known as Fox Rich, the center of the film, is the wife of Rob Richardson, sentenced to sixty years in Louisiana State Prison for a failed bank robbery. It was an act done out of "desperation," Fox Rich says. They and another were trying to start a hip hop clothing store, in Shreveport but an investor pulled out, and they were poor. Fox Rich was involved in the crime too, as the driver. She agreed to plea bargain and wound up doing 3 1/2 years. Rob wouldn't, and he got the big sentence.

The point of the jumping around is what? To make us feel the same powerlessness, perhaps, as Fox Rich and enter into her memories. The whole point is her struggle, her pain, and her determination, as she raises the boys, with help from her mother, into what looks like an impressive, good-looking brood. Fox Rich is a powerful, steadfast, determined woman, who we see often as an inspirational speaker in her self-defined cause talking to wives and families of prisoners about how incarceration of black people in America is slavery, and she is an abolitionist. At some times we see she has a car dealership, and recording a filmed advertisement, presumably for television. This is Fox Rich's portrait and that of her six sons, especially the twins, Freedom and Justus, born after Rob was imprisoned because she was pregnant when he went in.

The time-mix makes a dizzying continuum of the near twenty-year wait, reduced to only two visits to her husband a month, and the thousands wasted on lawyers who come up with nothing, while the boys go from chirping kindergarteners, junior high schoolers and high schoolers to college kids, and back again, and Fox Rich waits and controls her anger and pain as year after year she calls the white judge's office to find out what his response is to the latest appeal of the sentence.

As is often the case, I appreciate the artistry of this film, and above all the immediacy of its vivid personal portraiture, while still wishing it had at least sometimes been also framed in a more conventionally explicit form or included more conventionally explanatory material, more facts. But there are many strong moments here. Fox Rich is eloquent, and fascinating. All the different hair styles! The dignity, and the passion! Filmed by Bradley, Justus, a very handsome 18-year-old, perhaps, says, in crisp tones, "When my mother and father were arrested for robbing a bank" (with a confident click on the "k" of "bank"), "she wound up having a set of twins, one being myself, the other being my twin brother Freedom." He also says, "My family has a very strong image." (Here we see them assembled, adult, well dressed, at a public occasion.) "But behind that is a lot of hurt, lot of pain." And this film is a stirring portrait of that pain.

What stands out is Fox Rich's apparently unwavering loyalty to her husband, and to the cause of making a decent living and raising her sons right, in the racist South. Eighteen years for a minor bank robbery, a sentence of sixty? I guess they didn't have access to the right fancy lawyers. I guess they were Black in America.

The score is unusual, like the chronology, periods of conventional string music augmented by a tranquil piano performance by a now ninety-something Ethiopian nun called Emahoy Tsegué Guèbrou, found on YouTube.

Greg Nussen wrote eloquently of this film on Letterboxd: "Time is both a cinematic wonder and a heavy piece of political agitation. . . [it's] as much about the arbitrary nature of time as it is about the fallacy that forms the basis of the American justice system. Time that is 'served' and time that is taken away, time that is thrust upon victims of the system and time that is even gained. Prisons are neither places for rehabilitation nor a useful means with which to punish someone, they accomplish nothing of value except for the people that literally profit off it."

"Are we going to see him get out?" I think we wonder as we watch. Yes, we do, and it's worth the wait. Rob comes out in a T-shirt saying "NEVER GIVE UP." The return is joyous, sexy, and loving. Rob is not a cowed victim. He is presidential. At a celebration of many hugs he says the greatest value and the greatest faith is love and adds, "If it could be an acronym it would be Life's Only Valid Expression." These people have a lot of class. They're pretty awesome.

Time, 81 mins., debuted at Sundance Jan. 2020, and won the Documentary Directing award at Sundance and has won several other awards and nominations. It also showed at Miami Mar. 2020 and Sept. 20 at the virtual New York Film Festival, as part of which it was screened for this review, and is set for showing Sept. 24 at Zurich, Camden International (virtual) Film Festival, London and the Hamptons (virtual) Oct. 9. It is slated for internet release on Oct. 16 in the US and Oct. 23 in Canada.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-14-2023 at 11:08 PM.

-

NIGHT OF THE KINGS/LA NUIT DES ROIS (Philippe Lacôte 2020)

PHILIPPE LACOTE: NIGHT OF THE KINGS/LA NUIT DES ROIS (2020)

KONÉ BAKARY IN NIGHT OF THE KINGS

Night of the red moon

Night of the Kings/La Nuit des rois is a celebration set in Côte d'Ivoire and primarily in French, of improvisation, storytelling, and dramatic staging that also touches on the politics of control and the precariousness of life. Sometimes the narrative line may seem too much interrupted, but this is itself brilliant storytelling that impresses with its verve and flair and announces the arrival of a bold new talent from Africa. The setting is MACA, an overcrowded, disorderly prison in Abjijan, Cote d'Ivoire, in the middle of a jungle-park. "La MACA is the only prison in the world run by an inmate," someone declares. He is called Barbe Noire (Black Beard: Steve Teintchieu), and he is sick, and his authority is faltering. One called Demi Fou (Half Crazy: Digbeu Jean Cyrille) is a pretender for the throne. But he must contend with Lass (Abdoul Kariyi Konajé). The opening scene follows a new inmate as he arrives, riding rather grandly alone, in a yellow shirt, in the back of an open truck (Koné Bakary: but don't look him up: you'll find only Bakary Koné, a Cote d'Ivoirean footballer). He looks young and a little delicate, feminine (with a necklace), and yet also proud and strong. (The prison contains a truly effeminate young man, a cross dresser who's moved around, but never does anything). The prison throbs with energy. Guards or managers seem to stay in a room by themselves observing from a distance.

As soon as Barbe Noire sees the new arrival he impulsively decides to name him "Roman," a designated storyteller. This will distract the attention of the prisoners and prolong Barbe Noir's authority a little. What the new Roman doesn't know is that the Scheherazade-like tradition calls for him to tell stories for one night, a night of the red moon, and then he will be killed. Later Roman sees the iron hook at the top of the stairs and meets a strange old white man with a big bird on his shoulder (legendary French actor of Beau Travail and Holy Motors Denis Lavant) who tells him what his fate will be. Barbe Noire does not last the night, but Roman does.

There are only a few named characters, but this is very much an ensemble piece with a hundred extras who provide a surging energy. When Roman begins his storytelling, clad now in a handsome long blue silk shirt and standing on a box, there emerges a small company of self-appointed singers, mimes, and dancers around him who will act out, underline, and in the oral tradition, delay key moments of his tale.

How will Roman even survive a minute? He seems timid at first arrival, almost speechless. But when he speaks, scoffers are soon silenced. He announces he is a pickpocket, scoundrel, shyster - and common thief (cheers). He tells that he had an aunt who was a griot (oral bard), and he launches into a criminal epic close to his own experience - the life of Zama King - they know who he is - his own childhood friend, now a legendary crime boss, just arrested, head of the notorious e "Microbes" gang who rode in on an insurrection.

Roman weaves in legendary elements such as a king and queen (artist/hair sculptress Laetitia Ky) arriving long ago and a blind father for Zama, Soni (Rasmané Quédraogo). Bakary Koné holds his own as a dramatic speaker, but there's the chorus at hand, and scenes illustrating his tale, notably the king and queen arriving along the seashore, almost TV-footage of civil unrest, and Zama marching through a crowd with Roman on the periphery. Meanwhile time out for a quick feast, and for Barbe Noire to collapse and give up - making Roman's story just the framework for Lacote's effort to tell three stories, that of Roman, i.e. Zama King; of Barbe Noire; and the story of his own effort to weave things together into a very theatrical whole. As storytelling, no one of the three is totally convincing. But as cinema, this is a rich and tasty dish, deftly and economically weaving together many essential elements of an African life and culture shown to be still flourishing amid poverty, confinement, civil unrest and political upheaval. Roman nods to City of God, and a review for the Toronto Globe and Mail calls it "City of God crossed with A Prophet by way of One Thousand and One Nights." Indeed the final shot may link Koné Bakary's Roman with Tahar Rahim's Malik El Djebena in Jacque Audiard's prison epic. High ambitions; great models.

Night of the Kings/La Nuit des rois, debuted at Venice Sept. 2020, also included at Toronto and the New York Film Festival virtual edition, as part of which it was reviewed Thurs., Sept. 24, 2020 for this review. Coming to Chicago and Reykjavik in October. Metascore 82% (so many mainstream reviews).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-25-2020 at 01:28 AM.

-

CITY HALL (Frederick Wiseman 2020)

FREDERICK WISEMAN: CITY HALL (2020)

MAYOR OF BOSTON MARTY WALSH IN CITY HALL

Guy Lodge's Variety review lead off, "Frederick Wiseman’s Mammoth Boston Doc Shows Anti-Trump Politics in Practice."

The people who work for the city work for you"

"...My view is that these films are biased, prejudiced, condensed, compressed but fair. I think what I do is make movies that are not accurate in any objective sense, but accurate in the sense that I think they're a fair account of the experience I've had in making the movie."

First of all: Frederick Wiseman does not know boredom. Frederick Wiseman is interested in everything. Frederick Wiseman thinks we are interested too. Normally the "city hall" of an American city includes primarily the mayor's office and the city council, the city government. Last time in Monrovia, Indiana, Wiseman looked at a little town in the Midwest. Now he looks at one of America's great cities, Boston, Massachusetts, the biggest city in New England, one of the oldest large cities. It's also a city of racial and sectarian conflict, of warring ethnicities.

But Wiseman isn't looking at problems. He looks at institutions. Here, "City Hall" seems to encompass the whole city. And indeed in a liberal government the city government has a hand in, and responsibility toward, every part of that city. But this is also very largely a portrait of Marty Walsh, Mayor of Boston. He's everything that the President in Washington today (whom he refers to, but will not name) is not.

As we learn, Mayor Walsh is the son of Irish immigrants, and he is in recovery from alcoholism. He is a classic liberal with natural sympathy for immigrants, for people of color and other minorities, who boasts that during his five years in office, unemployment has sunk to 2%, and Boston has been named the easiest city in the country to get a job. He is an impressive individual. This film is like an advertisement for Marty Walsh. If he ran for President of the United States, I'd vote for him.

Did this film need to be four and a half hours long? I don't know. At times if you're paying attention to its many scenes - separated, as Wiseman had often done before, by montages of still shots of the city - you may wonder why some of them were included. People pouring over artifacts? A dog being examined by a vet? A school planning meeting? The kitchen of a man with an infestation of rats?

But we can say this film shows the wide reach of Boston's city government. Its responsibilities are myriad, and the sweep of the scenes pays homage to the range of Marty Walsh's caring and interest. He, like Wiseman, seems never to be bored. It particularly fascinated me that he took a Marine veterans' meeting as the opportunity to tell about his former alcohol problem In another scene already, about arts and recovery, it seemed, an articulate young man has said that recovery is all about stories. It's true. So here, Mayor Walsh tells the story of his alcoholism, suggesting that what an old lady says they used to call "shell shock" and now is called PTSD, is something that also requires the healing effect of telling your story to others.

As for the length, think of it as a way of conveying what it's like to sit through a day in any city hall, a day of meetings. The endless talk. Some of it, people telling their stories, which may heal them and us. Wiseman teaches us to be patient and listen, to the ordinary talk and everyday stories that are part of a comprehensive sympathy.

City Hall, 272 mins., debuted at Venice Sept. 2020 (Fair Play Cinema Award - Special Mention) and is scheduled for Toronto Hamburg, New York and Camden International (Maine) also in Sept. Screened online for this review on its virtual release date in the NYFF, Sept. 25, 2020. Metascore 89%.

Here's a review by a local resident. I mean to read it all. It's long, like a Wiseman film.

Opens Friday, November 13, 2020

in the Roxie Virtual Cinema

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-20-2020 at 11:05 PM.

-

DAYS 日子 (Tsai Ming-liang 2020)

TSAI MING-LIANG: DAYS 日子(2020)

ANONG HOUNGHEUANGSY AND LEE KANG-SHENG IN DAYS

The music box

Reactions range (on Letterboxd) from "a snoozer from start to finish" to "almost my favorite Tsai film" and a loving account from someone who has seen all ten of his films and flew to Berlin just to see this one in the festival, for his first big -screen Tsai experience, and felt well-rewarded, but had to endure bored and disrespectful audience members around him.

Among Tsai's films, though I haven't seen all of them, some of the main themes clearly are loneliness and lassitude and sex, or the implied desire for it, and for companionship. We get all that here in this unusually slow film featuring Tsai's longtime muse and life companion Lee Kang-sheng, along with a young Thai newcomer, Anong Houngheuangsy. (They are called in the credits respectively Kang and Non, but I'll just call them by their real names.)

This time Lee for the first time plays someone well off. Thus he occupies the rural compound here that Tsai and he actually moved into some time ago, and he can afford to fly to Bangkok and stay in a nice hotel room, where he will receive Anong, whom we've observed - and I do mean observed - patiently preparing a meal for himself in his rudimentary but airy digs and on duty in a food stall where he works. Later Anong reappears as a full service masseur, and I also do mean full service. The two men come together, the now fifty-two-year-old one, still suffering from the real-life neck ailment seen in The River and walking with a painful shuffle, and the twenty-something one, after an hour of this two-hour film has passed. Their encounter is the centerpiece and emotional core of this film typically suffused with sadness and loneliness but also with moments of warmth and gratitude, and always a feat of patient observation.

A slow film with long passages where not only the camera but its human point of observation is still, if it works for you, alerts you and awakens your sympathy and skill in observation. Since, unlike the Berlin presentation described by Francesco Quario on Letterboxd mentioned above, the New York version was virtual, we have the peripheral distractions Martin Scorsese has bewailed, and also the temptation to stop and start or interrupt or skip that may aid observation, or not, but disrupt the sense of an ongoing irresistible force you get in a movie theater, apart the glory of the Walter Reade Theater or Alice Tully Hall with their impressive screens and immersive sound systems.

As A.O. Scott observed in his New York Times review of Tsai's 2005 Wayward Cloud, those at all familiar with Tsai "will note that water is an important motif in his films," and in them "roofs and pipes are always leaking" on "lonely, alienated city dwellers." I understand from Giovanni Marchini Camia's detailed and admiring BFI review of Days, that more recently Tsai has made short films in non-urban locations, and also declared himself retired, or ready to retire. Francesco Quario has said this may be the last, though he would "gladly take a hundred more."

In the first half Lee gets an elaborate trad medicine treatment for his neck and backbone with wires and hot coals; before that he spends a long time staring out the window while water flows noisily. Water appears again as we watch Anong, in Bangkok, to whom we go back and forth from Lee, preparing a meal for himself of "fish soup, papaya salad and sticky rice" (Camia) on the floor, with a lot of washing food and water spilled on the floor around him where he squats. This sequence is a soothing alternative to Lee's pain and look of sadness, because Anong's food preparation is calm and methodical, almost happy, you might say. The only thing is - is it just for himself? Because it seems rather a lot of food; and we don't get much of a look at his consumption of it once he's done.

Then we come to Lee in the Bangkok hotel room. It's a large, simple, but well-appointed and peaceful room, with nice wood paneling. Methodically, Lee takes the cover off the big bed and folds it away, counts out money and puts the rest in a drawer. When the sequence of the massage by Anong (in jockey shorts) begins, Lee is already laid out face down, eyes closed. After a while he's asleep and snoring. Now Anong's patience and attentiveness to ritual we saw as he prepared a meal comes into its own as direct human kindness. With amazing delicacy his hands crisscross and circle up and down and over Lee's back. Many details suggest that as a masseur he's trained and knows what he's doing. And then, Lee is on his back, the caressing becomes sexual, the jockey shorts come off.

This sequence isn't pornographic, barely even sexual but rather, sensual and more simply patient, attentive, and touching. As Lee gets closer to satisfaction and there is tenderness and warmth in Anong's participation and they embrace and kiss with real feeling, and as with Anong's following Lee into the shower and continuing there to spray him and soap him and massage him, this is always modest and undramatic and real, but no mere mechanical servicing, for sure.

No wonder, then, when both have dried off and dressed they sit down together on the foot of the bed. Lee gives Anong a present of a little music box that plays the theme from Chaplin's Limelight, and Anong keeps winding it and winding it so the theme plays on and on; and here, Quario begins to weep and will go on weeping for the rest of the film.

Here also the dragging-on-and-on quality of the film takes on a new, plangent meaning, because it's saying these two lonely men, one weary and past middle age, the other young, don't want to part. And so there's a coda sequence to the encounter that happens outside, in a little Chinese noodle shop, where they sit together eating, facing each other - but not like the still: they're separated from us by a street full of loud passing traffic. Then there is blackness. And we rejoin the men, apart again and in different countries. As Quario has come to Berlin for Tsai's new film, Lee has come to Bangkok for a massage, and now we're all back at home.

At the end, Anong and Lee are alone again. And no one in this film has uttered more than a few words, and there have been by choice no subtitles.

I would say this is a pretty memorable film. I will not easily forget the sight of Anong later, after Lee is gone, sitting on a bench in noisy traffic, listening to the music box play the Limelight theme again, over and over and over.

Days 日子, 127 mins., debuted at Berlin Feb. 2020 (where it won the Teddy Award), showed at Taipei July, IndieLisboa Aug., and, where it was screened virtually for this review, New York starting Sept. 25. Also to be shown at London in Oct. 2020.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-29-2020 at 07:26 PM.

-

NOMADLAND (Chole Zhao 2020)

CHLOE ZHAO: NOMADLAND (2020) Centerpiece

FRANCES MCDORMAND IN NOMADLAND

Forced off the grid and choosing to stay there

At the outset of Nomadland,based on a book by Jessica Bruder, Chinese-born American filmmaker Chloe Zhao's second big feature after her remarkable The Rider (NYFF 2017), onscreen captions announce that in 2011 US Gypsum closed a factory and resultingly the town of Empire, Nevada collapsed. Proof: the zip code was discontinued. The movie follows Fern (Frances McDormand), suddenly a widow and set adrift by the town's collapse. Fern suddenly takes up life as a nomad, living out of her modified van and working the seasonal shifts at Amazon fulfillment centers, beet processing plants, or as part of a janitorial crew at an RV park, in a job found by her fellow migratory nomad, Linda May. Linda May is a real person. So are many in Nomadland - and the artistry of this film, and theirs, is that they're good playing themselves; and McDormand blends in well with them. Fern is not "homeless," she says, but "houseless." Not a strong distinction.

I confess my resistance to Nomadland, though it weakened somewhat past halfway through, then came back when the ending didn't seem to avoid sentimentality as The Rider did so well. This film shows with its grand old fashioned Searchlight Pictures opening that Zhao is more mainstream than I'd supposed. The Rider had a real person (wounded young cowboy Brady Jandreau) right at the center of it; it was about him. The new film has a famous actress, Frances McDormand, as Fern, at the center. That's very different. Another well known actor-person is on hand as Fern's would-be boyfriend on the road, David Strathairn. That relationship doesn't quite work out, and Straithairn doesn't quite convince. These presences of course make the movie more marketable, but otherwise a very different kind of movie, with a big producer and smooth strings-plus-piano score weaving the meandering storyline together.

As Fern meets many real persons in her wanderings and goes to new places this becomes a travelogue of modern hard times in the American West. McDormand, who's been in so many good movies, playing here one of the most central roles of her life, doesn't fail us here. But Fern is a cheery cypher, a soul who doesn't stay and doesn't share. Not that there aren't people like that out there, and maybe they're the kind who wander like this and resist offers of places to stay like with her sister Dolly (Melissa Smith) - meeting with whom, to get a desperately needed loan, is a defining moment. But there's not much of a story here. Maybe the main story is not the one about stubborn wanderlust but of harsh economic necessity, which some viewers think makes this film prophetic of future post-pandemic travails.

I'm with Michael Phillips, only more so, who in his Chicago Tribune review admits he finds Nomadland "a shade less wonderful than The Rider, with fewer sharp edges and a tad more contrivance." He says he loves it anyway. I don't love it. I can see, though, how it fits with a group of strong American movies about contemporary outlaws and wanderers who live off the grid. Its moments of checking in with settled people reminded me of Captain Fantastic; the saga to save the van seemed familiar. Personal favorites in this very American genre are Matt Ross's Captain Fantastic and Sean Penn's Into the Wild], and another recent good one is Debra Granik's Leave No Trace. (People make lists of off-the-grid movies.) At Walgreen's checkout the other day, I found there's a slick handbook for sale on "living off the grid." Maybe this is the lingering ingrown cold edge of the American pioneering spirit. Perhaps the widespread lust for such life helps explain how the US has done worse than any other country in the pandemic, because so many people refuse to follow rules.

Nomadland has, of course, some nice moments. It's rich with characters, notably "cheap RV" evangelist Bob Wells. Also touching is the drunken young man - I didn't catch his name - whom Fern gives a lighter to and whom she meets later and gives her another, prettier lighter (in this movie, alas, a significant event), and to whom she recites Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 ("Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?") to dress up a letter to his girlfriend. Lovely, thanks to Shakespeare. Only trouble is, in a film as busy and distracted and in love with sunsets and vistas as this one, a few nice moments aren't enough.

Nomadland, 108 mins., debuted Sept. 11, 2020 at Venice, winning the Golden Lion and two other awards, also showing in many other festivals, including Toronto (People's Choice award), New York (where it was viewed, as the Centerpiece film, for this review), Helsinki, Reykjavik, Zurich, London, Hamburg, the Hamptons, Montclair, and more. C̶u̶r̶r̶e̶n̶t̶ Metascore 9̶8̶%̶ 89%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-14-2023 at 11:09 PM.

-

THE DISCIIPLE (Chaitanya Tamhane 2020)

CHAITANYA TAMHANE: THE DISCIIPLE (2020)

A STILL FROM TAMHANE'S THE DISCIPLE

Trapped in the pressures of musical tradition in modern India

The Disciple is a fantastic, complex and quite unexpected film about the undermining of cultural tradition and the pressure on a fledgling practitioner of traditional art to achieve an inaccessible perfection. Of Tamhane's debut film Court, shown in New Directors/New Films 2015, I wrote, "All the romance has been drained from our vision of India by the time we've experienced this complex, mind-boggling, convincing film." This sophomore effort isn't quite as grim as that meandering, ironic picture of India's corrupt, bureaucratic judicial system, but here again Tamhane gives us a disturbing, challenging watch that takes on central aspects of Indian life. Tamhane is a remarkable, uniquely thought-provoking filmmaker, a significant new cinematic voice from India.

The main character is a not-so-young man called Sharad (real musician and fledgling actor Aditya Modak) who wishes to become a significant performer-singer of Śāstriya Saṅgīt, North Indian classical music, aka Hindustani music. This music dates from the 12th century when it branched off from far older music. We know if from the sitar maestro Ravi Shankar, who brought it to the West. He taught us about ragas, and that there were morning and evening ones: here we learn that there are numerous more specific ones even little boys, in some families, are supposed to know the names of. We also learn that yoga and yogic meditation are elements in the mastery of this art. Khayal is the tradition of improvisational singing, and it comes from the Arabic word for "imagination," but all the rest of this film is in Marathi language with a few moments and frequent words in English.

Once I heard Ravi's sister-in-law Lakshmi Shankar: her singing had technical perfection and an otherworldly beauty. But a difficulty here is that we don't know this highly improvisational yet deeply traditional music well enough to know when the singing is good or not. And it's important to know that Sharad, who is riddled by doubt, may not be good enough - or not good enough yet. Modak must be conveying that, but can we appreciate it? We hear frequent excerpts from classical Indian music concerts, which may seem beautiful and calming, but also trouble us with trying to figure out where they fit in today's India and where Sharad fits in.

Sharad lives with and cares for his aged guruji (Arun Dravid, a master of khayal), who is very severe with him always and seems to suggest he won't make the grade, that his performances are too bland or repetitious. The worst of it is Sharad is criticized by his guru under his breath in joint public performances where the student tabla player and young female singing sitar player seem accepted by him as successes. He also listens to tapes - we hear them as we see him in slow motion riding in the evening on the astonishingly deserted Mumbai freeway on his motorbike - the sharp voice of Maai (Sumitra Bhave), a legendary woman, his guru's guru, whose singing was never recorded, but who pronounces on the relentless demands of the art and the absurdity of paying attention to conventional standards or performing for audiences. (It turns out Sharad's father was a student of Maai, but a mediocre one; it's on him to do better.) "I sing only for my guru and for my god," she says, her "god" presumably being Sarasvatī, the Hindu goddess of knowledge, music, art, speech, wisdom, and learning; in her Wikipedia picture she is seen playing a sitar with two of her four arms. The slow-mo motorbike ride with the guru's guru is a repeated signature image, one of the ones we take away from this complicated, often troubling flim.

Sharad does some tutoring of young boys with a harmonium. But Sharad's mother, who thinks he keeps the boys too long working, keeps telling him to get a real job, or any job job, which he rejects. Yet he must pay his guru's medical bills. He does work at a recording business under Kishore (Makarand Mukund) selling CD's made from tapes of obscure Indian classical music artists.

Sharad is initially only 24, and by tradition he must be a student till he's 40, and only then can get married; he tells his mother a divorcee or widow will be okay. Meanwhile, he masturbates, the film frankly shows, to the inspiration of online porn. He surfs and finds an unflattering video of himself performing, more noise in his dedicated life. The years go by, and we see him at different stages, with and without a mustache.

Always there is the threat, further out, of Hindustani music's degeneration or corruption or simply fading out thorough lack of interest or lack of understanding or lack of audience. The idea of "fusion" corrupting the music comes several times, first close to home from a student offered a job in a "fusion" band asking (through his mother) Sharad's permission to take it - his consent is withering in its disapproval; then on TV, from Shaswati Bose (Kristy Banerjee), a young woman contestant on a reality music competition show called "Fame India" who starts out with a minute or two of classical performance. The judges congratulate her on her voice and it's "on the Mumbai!" From then on she becomes a pop/Bollywood fusion star Sharad must be watching in horror. It's all the pain of not being appreciated when the tradition you are following is the pure, true one and what is admired all around is a debasement, or something from abroad.

Worse yet debasement comes from within, when Sharad has a meeting arranged by Kishore with Rajan Joshi (Prasad Vanarse), a renowned music critic who clams to know all - he's quite convincing - and who promply, while consuming a whisky and soda, trashes both Sharad's guru and even Maai, whom he speaks of in the most humiliating terms imaginable. It's a brilliantly written scene, pushing the situation to the limits without overstepping credibility. You acutely feel its sting, and Sharad's rage and sense of insult.

How it all ends we don't really know from a final brief scene that appears happy but leaves the outcome of all that's gone before uncertain. Tamhane, who wrote, directed, and edited this film, is all the more proven a true original from this second example. But he remains austere, as indicated by the work of his dp Michal Sobocinski, who provides many unflashy establishing shots and photographs the real live concerts from a discreet distance. We are lucky to have this fiercely intelligent new director from India.

The Disciple, debuted at Venice Sept. 4, 2020 to general acclaim, winning there Best Screenplay, the FIPRESCI Prize, and the Golden Lion (Best Film). Reviewed enthusiastically there by Jay Weissberg in Variety and Deborah Young in Hollywood Reporter. Also shown at Toronto, Zurich (nominated for best international feature), New York and London. Screened for this review as part of the virtual NYFF Sept. 29, 2020. Executive produced by Alfonso Cuarón. Metacritic rating 83%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 06-25-2022 at 09:55 AM.

-

THE SALT OF TEARS/LE SEL DES LARMES (Philippe Garrel 2020)

PHILIPPE GARREL: THE SALT OF TEARS/LE SEL DES LARMES (2020)

OULAYA AMAMRA AND LOGANN ANTUOFERMO IN THE SALT OF TEARS

Lucky Luc

Philippe Garrel is a regular in NYFF Main Slates, perhaps for his classic French style and stubborn independence as a filmmaker. The look here is handsome, the storytelling is economical, and the actors are all good, but Garrel senior begins to seem more and more an inexplicable anachronism, his blindly chauvinistic point of view downright shocking this time, though maybe for some the storyline here may seem simply novel. And always there is the old fashioned framework, the rich black and white images, the frequent voiceover narration using the formal passé simple tense. Garrel collaborated again here with the prolific screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, now 89, who worked in an almost surreal "exquisite corpse" style with Garrel's son Louis recently on the latter's second feature as a director, A Faithful Man (NYFF 2018).

It's all from the point of view of lucky, clueless, avowedly cowardly Luc (Logann Antuofermo), son of a carpenter, living in the provinces. He meets a girl of Arab origin and impressive hair at a bus stop in Paris, Djemila (Oulaya Amamra), and from this springs a connection. We have to grant that Garrel writes his women pretty dumb too, since it's well goofy of Djemila to fall instantly for a guy who hardly says a word to her. Luc seems to connect just by staring. Luc explains to Djemila that he's only in Paris to apply to a famous and prestigious training program for ébénistes, cabinetmakers, the Boulle School. He quickly gets her into his bed, but she won't go all the way. Nonetheless when he soon returns to the provinces, she's devastated.

It's surprising that Garrel spends so much on this relationship and makes it the first, emotional, one and the most memorable. One really does feel the power of the long exchanged looks. When Djemila tells Luc he's very "doux" (sweet, gentle), at that point it seems convincing and rather interesting. The actor radiates warmth, sexuality, and yes, gentleness. He tells Djemila he'll "never forget her." In these days of email and cellphones, this too is an anachronism, because of course, it's easy to keep in touch. Back he goes to his carpenter father (André Wilms), with whom he lives. Later Luc confesses (through the voiceover) to his "lacheté" toward Djemila, his cowardice.

Eventually we see that the only human Luc cares about is his father, and that's the one relationship in this film of real depth. The movie has two other women up its sleeve for Luc, neither of whom will really matter, though number three is ostensibly the charm, the keeper. Ant the plot jumps the shark later on, and I began to lose track, or cease to care. Immediately upon his return home, Luc runs into Geneviève (Louise Chevillotte, seen also in Gerrel's 2017 Lover for a Day, NYFF 2017)Geneviève instantly pops into bed with Luc - or do they have sex in the bath? She is hot for her Lycee lover from six or seven years earlier, no questions asked. This goes on for a while, and then Luc gets the letter of acceptance to the Boulle School, which makes his dad cry: he never made it that high in the French carpentry pecking order. Needless to say, this, like Garrel's kind of filmmaking, is an antique craft.

Before Luc leaves home for school, when he has promised Geneviève they'd see each other every other week, she breaks down and confesses to him she is pregnant with his child. Far from delighted he is furious and yells at her, saying she has "betrayed him," since this isn't a responsibility he is ready for, financially or otherwise. Clearly not. His departure is cold, and he isn't in touch. Geneviève, like Djemila, has admittedly been foolish to fall into this relationship again so heavily. Can't she see how shallow Luc is?

Need we say that soon after he gets set at éboniste school, a personable black colleague, Jean-René (Teddy Chawa), sets up a double date for the two of them with two nurses, he with Alice (Aline Belibi), Luc with Betsy ( Souheila Yacoub)? Before you know it or the action has accounted for it Luc and Betsy are living together and then, with Paco (Martin Mesnier), a coworker of Betsy's who - needs a place for a while. Paco must endure the sound of Luc and Betsy's lovemaking, there's no way around it. Luc has to get up very early for cabinetry school leaving Paco and Betsy in bed in their small apartment, since they work later, and - that's the kind of world this is - Luc has to worry that Betsy could also be popping into bed with Paco.

The last part of the plot shifts the attention to Luc's father, perhaps a figure of more weight - but it's too late. My first experience with Philippe Garrel's films was the best one: the drawn-out, dreamy, ultra-sad evocation of late sixties Paris, Regular Lovers (NYFF 2005). A couple times Garrel senion has evoked his own famous, druggy failed love affairs effectively. But this is a tale that's hard to swallow.

The Salt of Tears/Le sel des larmes, 100 mins., debuted at the Berlinale Feb. 2020, opened in Paris theaters in July (AlloCiné press rating 3.5). Screened for this review as part of the virtual New York Film Festival Sept. 29, 2020. Also slated for Moscow Oct. 4. A Distrib Films release.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-03-2020 at 05:57 PM.

-

FAUNA (Nicolás Pereda 2020)

NICOLÁS PEREDA: FAUNA (2020)

LÁZARO GABINO RODRIGUEZ AND LUISA PARDO (WEARING WIGS) IN FAUNA

Meeting up and making up

The 38-year-old Mexican-Canadian filmmaker Nicolas Pereda's Fauna is not part of the elite but more mainstream Main Slate but from the NYFF's "new and innovative" Currents series - a collection one needs to approach with an open mind. Pereda is working in an intentionally disjointed ironic minimalist manner. Partly this seventy-minute feature is dead serious, touching on Mexico's pervasive "narcos" issues in the first half and alluding to a disappeared activist miner in the second. But it's also playfully absurdist in its references to making up stories and acting. Little happens here and less makes fully coherent sense - the hardest kind of movie to summarize. But one hangs on every word as one did long ago with the plays of Eugène Ionesco. Pereda is clearly a sui generis original. This review constitutes a first look. I don't know what all this "means," but one is in a distinctive world. Pereda is a semi-surrealist/semi-abstract painter delighting in his ability to shape his own world at will, and his medium is his actors and his scenes.

Pereda likes to work with a few actors who are his friends. Critics complain this film is too offbeat and nonsensical to make any political points, but he wouldn't care; he has an international following and has received international accolades (see below). This is work that in part fits in with a playful strain in Latin American filmmaking one finds in Alonso Ruizpalacios (of Güeros ) or Alexis Dos Santos of the 2006 Glue, or the films of Fernando Eimbcke and even Gerardo Naranjo, though I don't quite see their charm here. He might owe something to the Iranian master Abbas Kiarastomi; one thinks of his Certified Copy.

Cigarettes, as in old Hollywood movies, are key narrative devices. Two siblings arrive separately in a small mining town to visit their parents. Sister Luisa (Luisa Pardo) is with boyfriend Paco (Francisco Barreiro); both are actors. Luisa’s estranged brother, Gabino (regular Pereda collaborator Lázaro Gabino Rodríguez), comes on his own. They both use GPS which doesn't work very well, and when the GPS tells them they've arrived at their destination, they don't believe it.

Paco goes to buy cigarettes; he and Gabino are both out. A guy has just bought out the little local shop and Paco begs the man to sell him and the man bargains hard. One gets the impression Paco has paid two or three times the price and been forced to buy two packs. Then when he goes inside, the man who has reamed him is Luisa's father (José Rodríguez López). Gabino insists on paying Paco 40 pesos for one pack. But when Paco tells him he's paid more than double, Gabino gets annoyed an demands the 40 pesos back.

Everyone seems disgruntled. They sit down to eat, but dad says the food tastes off and insists they go out, for "pizza," of to "the Oasis." At the Oasis, dad insists that since Paco has said he has a role in the "Narcos" TV series, he perform one of his scenes. Paco protests that so far, he has not had any lines. Dad still insists, so he does a mute scene. Not satisfied, dad presses further, insisting he should just make up lines. Paco winds up doing a whole scene speaking the lines of the lead actor in the series. Barriero really is in "Narcos" as a minor member of the Arellano Félix cartel family, and the lines he performs are actual ones that Pereda has painstakingly transcribed. When Paco has done the scene, dad presses him to do it again.

At night, Luisa is lying in bed with her mother, but can't sleep because she's nervous over an acting role. She wakes her mother up, and says the lines. Her mother says she's fine, but she would say them differently. She then does say them - and damned if she doesn't say them much better.

The second half is more fanciful, growing largely out of a slim novel that Gabino is reading. Luisa asks him to describe the book, and he proceeds to do so, apparently freely improvising. This becomes "a mystery involving a missing activist, an amateur investigator (Rodríguez), twin sisters named Flora and Fauna (both played by Pardo), a low-level criminal (Barreiro), and an unseen group of narcos with nefarious ties to the local mine." (I'm quoting from a long discussion of this film and interview with Pereda by Jordan Cronk in Cinema Scope, where readers may go if they want more information.)

But here, just as the jokey disagreeableness of the first part undercut the serious references to Mexico's drug cartel problem, jokes about Gabino mistakenly entering Fauna's room when they're staying at the same motel and "stealing" her towel and playful references to the fact that this is all about fantasy and imagination, disguise (because the actors are using wigs, Gabino with a full head of hair covering his shaven head), and the idea of improvisation and performance, undercut the references to gangsters involved in the mining industry and disappearing an investigator.

Many themes crop up in these sequences, but a key one is manipulation, the ability to alter the direction of others but the likelihood of oneself being misdirected.

Nicolás Pereda has made nine feature films, two medium-length films and two short films that have been presented at festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno and Toronto, as well as in art galleries such as the Reina Sofía in Madrid, the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris, the Guggenheim and MoMa. His work has been the subject of 36 retrospectives worldwide at venues such as Anthology Film Archive, Pacific Film Archive, Jeonju International Film Festival, TIFF Cinematheque and Cineteca Nacional de México. He has received 30 awards in national and international festivals. In Mexico he has won the award for Best Mexican Film at the festivals of Guadalajara, Morelia, Guanajuato, Ficunam, Monterrey and Los Cabos. In 2010 he was awarded the Orizzonti Prize at the Venice Film Festival.

Fauna, 70 mins., debuted at Toronto Sept. 16 and showed starting Sept. 19, 2020 at the virtual New York Film Festival, as part of which it was screened online for this review. It is also scheduled for the AFI Latin American Film Festival Sept. 27.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-22-2020 at 01:42 AM.

-

MLK/FBI (Sam Pollard 2020)

SAM POLLARD: MLK/FBI (2020)

How the FBI hounded MLK and let him die

This is above all, a film that organizes things for us, things we may already know. It focuses on key dates. I'm not sure if there is a whole lot new here for one well acquainted with the US in the sixties. Tis may be the first film to uncover fully the extent of the FBI's surveillance and harassment of Martin Luther King, Jr. But what emerges that may be most fresh is a different sense of the mood of the country, what white Americans in general thought and felt. It's also a good-looking film. As is often the case now with modern digital editing techniques, everything looks snappy, and it's made stylish and unified by being almost entirely in brilliant black and white. It's a good choice not to have talking heads seen but archival footage, with the voiceover identified discretely by a name in the corner.

What we particularly need to know is that after the milestone March on Washington (August 28, 1963), with MKK's famous "I have a dream" speech, an example of his leadership, eloquence, and ability to rise to the greatest occasion, the number two man at the FBI, W.C. Sullivan, director for domestic intelligence operations, declared King to be "the most dangerous Negro in America." And they set upon him with all their ability to follow and snoop, with wiretaps and later "bugs" and officers in next rooms listening wherever King went. This film makes clear that this suspicion was not peculiar to the FBI, least of all the paranoia of FBI boss J. Edgar Hoover, but typical of the mood of the country at that time. Glimpses of many films show how Americans were indoctrinated in an admiration of the FBI. Women admired the agents and thought them sexy; little boys wanted to grow up to become them.

They found King relied heavily on a lawyer, Stanley Levinson, who was a former communist. He was brought up before the notorious HUAC, the House Un-American Activities Committee. President Kennedy met with MLK and warned him he must not associate with Levinson. King promised he would stop. This was a lie: he continued to see him.

I lived through this period, but this film has helped me see that I may very well have experienced it differently from a majority of white Americans. For some of us, the civil rights movement in the South was stirring; Reverend King was impressive; Black Power seemed right, the Panthers in Oakland a force for good. Many white Americans felt threatened. They saw the demonstrations and non-violent battles King led as did the UPS reporter Gay Pauley, who questioned King hostilely on air, as ending in blood, and hence dangerous and disruptive. King does not lose his cool, and has a good answer. But probably for many viewers, the questions were more important than the answers, and expressed their point of view.

For the FBI and perhaps much of white America, Black activism was as threatening and dangerous as communism and indistinguishable from it. The FBI feared "the rise of a Black messiah" in the success of MLK.

This film goes easy on J. Edgar Hoover. It describes his private life as "problematic," and quickly runs a montage of him with his male longtime companion. But Sullivan and Hoover together had it in for MLK.

When they ramped up their snooping on King, they soon discovered he had multiple extra-marital relations. From then on this became the major focus of their investigations of King. They gathered more and more data, and in private spoke with horror and disgust of King's sexual affairs, as filthy and disgusting. Coretta Scott King probably knew of them; in one clip she says she knew King better than anyone, as if to say so.

Next important date: November 22, 1963, the assassination of President Kennedy. President Johnson pushed through the Civil Rights Act as a memorial to Kennedy, and signed it June 2, 1964. In October 1964 MLK received the Nobel Peace Prize. This is shown. There is a bit of sexist condescension in the explanation that Coretta would indeed accompany him to Stockholm, even though she was the mother of four. (They didn't know the Nobel Committee would probably pay for the children to come too.) At the signing of the Civil Rights Act, King is standing close by; J. Edgar Hoover is hovering in front.

You can't say Hoover was merely a typical American in his growing hatred of King, which flamed out after the Nobel Prize, when he publicly declared "Dr. Martin Luther King is the most notorious liar in the country." At this point, the film shows, they started sparring, and eventually met up and supposedly spoke amicably.

Eventually there were "fifteen incidents" of MLK with women which the FBI made public, but the press, honoring King's reputation much enhanced by the Nobel Prize, didn't reveal these things. The FBI simply went on hounding King and eventually threatened and confronted him.

Finally the FBI sent King and his wife a tape compendium of recorded moments of him allegedly with other women in sexual situations along with a letter suggesting that he was utterly ruined and should kill himself. Clearly the FBI was off the rails in its persecution of King by this point. Former (2013-2017) FBI chief James Comey in voiceover says "this represents the darkest episode in the FBI's history." One may suspect King is not the only individual hounded this way, but we must take Comey's word on this.

From here on, King reportedly led to an "emotional crisis" for King, and he appeared increasingly agitated, though it's also said that he was too busy to obsess about the FBI's persecution of him. A decisive change came when, reportedly here inspired by a Ramparts article publishing photos of Vietnamese children disfigured or maimed by US napalm, King chose to speak out in opposition to the Vietnam war at last. When he did so decisively in his now well known speech in New York's Riverside Church, this meant he had cut himself off from the White House, as he acknowledged. The film reports that the press berated King for this stand: it shows multiple newspaper op-ed articles against him.

MOre details follow: notably, COINTELPRO, the FBI's massive program of surveillance and infiltration of political groups judged to be "subversive" (well covered in other documentaries). By this point, it's noted, Black activism was more a target than communism. This film names two Black undercover FBI agents who infiltrated Black activist groups: Ernest Withers, eighteen years an agent, and Jim Harrison.

MLK went on, instrumental in organizing the Poor People's Campaign, a program that was multi-racial, and further reaching than the previous civil rights movement. He was growing and changing (like Malcolm X), and we can only imagine what he might have achieved if he had lived beyond the age of thirty-nine.

King's leadership in the PPC was cut short by his assassination on April 4, 1968, which came the day after one of his best speeches, the film suggests - an alarm about crack-downs on the right to free speech in America that he had observed happening all over the country. For a while, the film ponders this event: clearly, the FBI followed King so closely, why didn't it see an impending assassination and stop it. Indeed.

MLK/FBI, 104 mins., debuted at Toronto Sept. 2020, and showed at New York, as part of which it was screened (virtually) on its NYFF release date, Sept. 25. Also slated for Chicago and putative US theatrical release Jan. 15, 2021.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-28-2021 at 07:31 PM.

-

ISABELLA (Matías Piñeiro 2020)

MATIAS PIÑEIRO: ISABELLA (2020)

MARIA VILLAR AND AGUSTINA MUÑOZ IN ISABELLA

In which the young Argentinian still proves opaque

Argentine filmmaker Matías Piñeiro (previously reviewed here, Viola (ND/NF 2012) and The Princess of France, (NYFF 2014) is not a director whose work I've liked. But I'm back again, because how can one dislike something based on Shakespeare? Perhaps I just didn't get it and need to try harder. This year's NYFF blurb says Piñeiro again refers to Shakespeare, this time to "anchor a loose yet intellectually rigorous examination of life’s loves," etc. This makes the last five out of his filmography of ten films, if we count shorts, where he has done something like this; this is his sixth feature. For tis one, after a detour to New York (where he now lives) for his last, Hermia and Helena - not reviewed here - Piñeiro returns to his native Buenos Aires, including some beautiful country scenes shot in Argentina's Córdoba Province.

But what makes it tricky is Pineiro isn't just riffing off a Shakespeare text, but doing that indirectly while focusing on actors auditioning or rehearsing, who of course have personal issues of their own. And he very much makes use of a small personal company of players and friends he has been using repeatedly in these films, which may lead to inside references and jokes. Regulars include María Villar and Agustina Muñoz as, respectively, Mariel, a teacher with stage aspirations, and Luciana, a more established actress. The focus shifts back and forth between the lead-up to a crucial audition and a time years later.

And this time then there is the thing of the colors and the stones. The film begins with a beautiful sunset where the sky is violet, red, purple. At one point the stones are used to refer to a tone, when acting or speaking. There is also a ritual of twelve stones that are thrown.

As David Erlich notes on IndieWire, Piñeiro eschews establishing shots here that would show us where we are so it all seems to happen in a neutral present. "In many respects," writes Erlich, "this feels like an exercise that was [more?] important for Piñeiro to make than it is for us to see; playful but seldom fun, it’s the rare film so ensconced in its characters’ headspace that it doesn’t seem the least bit conscious of the fact that it’s being watched." Erlich thinks Piñeiro is ready to leave Shakespeare behind. Or at least he hopes so.

A writer for Criterion, Joshua Brunsting, calls Isabella "Easily the filmmaker’s most obtuse and elliptical work." If so, since that's been the problem all along, my choice to watch another of Piñeiro's similarly constructed movies seems like an ill fated one. Brunsting (I'd say) clarifies the film more than Erlich, in particular explaining the meaning of the constant moments showing color swatches and differently shaped stones, which partly refer to the main character Marion's later involvement in an art project similar to a color-and-light installation by James Turrell (the color compositions also very much resemble the work of Josef Albers). These represent different emotional tones. It's this film's "tonal and narrative shifts" that, Brunsting writes, make it a "densely layered work."

As we watch we clearly grasp, many times over given Piñeiro's habit of repetition, that Mariel (Maria Villar), who when initially seen is pregnant, as well as in need of funds, is in a kind of competition with Luciana (Agustina Munoz), a more successful actress who's involved with Mariel's estranged brother (Guillermo Solovey, relatively only glimpsed here), who is putting on the production of Measure for Measure in which Mariel would like to win a role. And as is gradually and repeatedly made clear, Luciana gets the role of Isabela (Isabel in Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, which is being put on in Spanish). Mariel renounces acting, and later, is involved in art projects.

The key scene in the play, shown only once in an audition with Mariel, comes when she stands before a judge who offers to release her brother if she will give herself to him. But Mariel's brother, who reads the judge's part in her audition, gives the role to Luciana.

As I have said before, a Piñeiro film works very well for professors or students to analyze, but not so well to watch. In a recent Brooklyn Rail interview with Piñeiro by Jessica Dunn Rovinelli, it's obvious he has only a vague idea what the colors and the stones mean, though he has external reasons for using them. He admits he knows very well where every segment in the time-shuffled film fits in the chronology, but he doesn't mention the viewer. For the editing, Piñeiro says it was "a little bit like doing a puzzle." He admits he tackled a jigsaw puzzle of a Jackson Pollock painting and "failed big time."

This time I watched Piñeiro's film and didn't try too hard to follow it. I just sat back and let the copious dialogue wash over me, enjoying the walks in the grasses of Córdoba Province and the play with colors and light, especially purple. The color, Piñeiro tells Brooklyn Rail, helps relax you. Otherwise, it's a Jackson Pollack jigsaw puzzle.

Isabella, 80 mins., debuted at Berlin Feb. 2020, showed at IndieLisboa in Aug., and was screened for this review as part of the Sept. 17-Oct. 11, 2020 virtual and drive-in New York Film Festival where it showed starting Sept. 24.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-29-2020 at 09:38 AM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks