-

Art of the Real previews; Jarmusch retrospective, FSLC

Art of the Real

Jim Jarmusch retrospective at Lincoln Center

A Film Society of Lincoln Center series that interprets documentary in the widest possible sense. I expect to provide screening notes on the following films of the series. I'll also attend one film from the complete retrospective of Jim Jarmusch, Dead Man. General Forum thread for discussion of these topics here.

ART OF THE REAL

April 11 - 26, 2014

The Film Society of Lincoln Center's new annual series Art of the Real is a nonfiction showcase founded on the most expansive possible view of documentary film. The inaugural edition features new work from around the world alongside retrospective selections by both known and unjustly forgotten filmmakers. It is a platform for filmmakers and artists who have given us a wider view of nonfiction cinema and at the same time brought the form full circle, back to its early, boundary-pushing days. Co-programmed by Dennis Lim and Rachael Rakes.

Focus on the Sensory Ethnography Lab

In a mere eight years, the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard University has gone from an unusually ambitious academic program to one of the most vital incubators of nonfiction and experimental cinema in the United States. The films in this selection, including work produced at the SEL and work that inspired SEL makers, attest to the aspirations of sensory ethnography: to experience the world, and to transmit some of the magnitude and multiplicity of that experience. Presented in collaboration with the 2014 Whitney Biennial.

Click on the title above for the full program. I'll comment on just a few of the offerings.

PERMANENT VACATION: THE FILMS OF JIM JARMUSCH

April 2 - 10. 2014

Over the course of a single-minded yet constantly surprising career that has now spanned more than three decades, Jim Jarmusch has become a beloved, forever-cool icon of independent American (and world) cinema. His movies combine a romantic wanderlust, a sense of humor both humane and deadpan, and a connoisseur’s appreciation of the highs and lows of art and popular culture (Elvis Presley, Yasujiro Ozu, and William Blake, for starters). This complete retrospective—which includes 11 features and several shorts and music videos—leads up to the upcoming release of Jarmusch’s latest feature, Only Lovers Left Alive (a selection of the 2013 New York Film Festival, opening at the Film Society of Lincoln Center on April 11). Jarmusch’s latest exquisite genre reinvention, the film is a paean to the pleasures of long-term relationships in the guise of a vampire movie. It also strikes a pitch-perfect balance of melancholy and joy, and celebrates art’s enduring power to re-invigorate one’s experience of the world—something that could be said of all the films in this retrospective. Film Society of Lincoln Center page for this retrospective.

JIM JARMUSCH FILMOGRAPHY

1980 Permanent Vacation

1984 Stranger Than Paradise

1986 Down by Law

1989 Mystery Train

1991 Night on Earth

1995 Dead Man

1999 Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

2003 Coffee and Cigarettes

2005 Broken Flowers

2009 The Limits of Control

2012 Only Lovers Left Alive

I will view at Lincoln Center and comment on Jarmusch's Dead Man (1995).

Links to the reviews:

Actress (Robert Greene 2014)--AOTR

Bloody Beans (Narimane Mari 2013)--AOTR

Change of Life/Mudar de Vida (Paulo Rocha 1966)--AOTR

Dead Man (Jim Jarmusch 1995)--Jarmusch retrospective

Red Hollywood (Thom Andersen, Noël Burch 1996; reformatted 2013)--AOTR

La última pellícula (Ray Martin, Mark Paranson 2013)-AOTR

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2014 at 01:00 PM.

-

LA ÚLTIMA PELLÍCULA (Ray Martin and Mark Peranson 2013)

RAY MARTIN AND MARK PERANSON: LA ÚLTIMA PELLÍCULA (2013)

LA ÚLTIMA PELLÍCULA

An egocentric filmmaker talks about himself, and the apocalypse, and the end of film, in Mexico

"In this documentary within a narrative—and vice versa—a grandiose filmmaker (Alex Ross Perry) arrives in the Yucatán to scout locations for his new movie, a production that will involve exposing the last extant celluloid film stock on the eve of the Mayan Apocalypse. Instead, he finds himself waylaid by the formal schizophrenia of the film in which he himself is a character. Simultaneously a tribute to and a critique of The Last Movie (Dennis Hopper’s seminal obliteration of the boundary separating life and cinema), La última película engages with the impending death of celluloid through a veritable cyclone of film and video formats, genres, modes, and methods. Martin and Peranson have created an unclassifiable work that mirrors the contortions and leaps of the medium’s history and present." -- Art of the Real FSLC blurb.

In the event, this Shandean ramble does contain some lovely imagery, but it's more impressive in the concept than the execution, which of course fits very well with the nature of Lawrence Sterne's eccentric masterpiece itself. Of course there was no quetion of using "the last celluloid stock." Some directors (like James Gray) still insist on using film, and some of the very best use film in whole or in part, including Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson, Christopher Nolan, Rian Johnson, and Stephen Spielberg, besides Alex Ross Perry, though oddly, in some scenes where Perry is supposed to be scouting for a location in Mexico, he's holding a small digital video camera. And ironically, this film was screened for the press in digital form, though a 35mm. print was to be shown to the public. My favorite part of this rambling, not always interesting film is the sequence when Perry walks around ranting against the wealthy looking American hippies in odd looking clothes right in front of him who have assembled at the Mayan temple to adopt ridiculous odd "meditative" poses on the eve of the apocalypse. But the weakness of the film is that it's better in Perry's monologues, grandiose and repetitious as they are, than in anything "cinematic" that's included. Of course the many film formats introduced and the distressed effects on some of the imagers, as well as the highly saturated landscapes at dusk add interest and beauty, but such things can't take the place of structure and interesting content. La Última Pellícula often seems like a film class effort, carried to an extreme and done by an adult. In his Toronto review for <a href="http://variety.com/2013/film/reviews/toronto-film-review-la-ultima-pelicula-1200657690/">Variet </a> Dennis Harvey pointed out that this flimsy spoof of Hopper's The Last Movie will "fly over the heads of most viewers" at best because Hopper's film has been little seen.

La última película, 88 mins., was screened for this review as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center's Art of the Real series, and this film does fulfill the series' interest in work that pushes the boundaries between documentary and fiction in new ways. This film is shown in the Art of the Real series at Lincoln Center Friday, April 11, 2014 at 6:30pm.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 03:17 PM.

-

CHANGE OF LIFE (Paulo Rocha 1966)

PAULO ROCHA: CHANGE OF LIFE/MUDAR DE VIDA (1966)

MARIA BARROSO IN CHANGE OF LIFE

A classic Portuguese film combines neorealism with elements of fairy tale

"A soldier [a disenchanted veteran of the Angola war] returns home to a Portuguese fishing village that has changed during his absence in Paulo Rocha's masterpiece of “sculpted reality,” a direct response to his mentor Manoel de Oliveira's Rite of Spring.. . . Paulo Rocha's second feature, conceived as a direct response to his mentor Manoel de Oliveira’s Rite of Spring (which Rocha worked on as well), is a masterpiece of 'sculpted reality,' using fictional conceits and non-actors cast as themselves to create an ethnographic portrait of Furadouro, a remote Portuguese fishing village. The dramatic premise, about a soldier returning home to a place that has changed in both subtle and obvious ways during his absence, serves as a pretext for Rocha to respectfully examine the specificities of Furadouro's people, their daily routines and rituals, and their evolving relationships with the village’s history" --Art of the Real FSLC blurb.

Certainly one of the finest, most seamless examples of docudrama ever seen. This beautiful and haunting film by Rocha, the central figure of Novo Cinema, requires far more study and explanation; a single viewing is inadequate. The first point that must be made is that it's confusing to watch it because the "digital projection" it's now cast in makes it look as fresh as a daisy, as if it were made last year and the filmmaker had miraculously found a group of Portuguese fisherman and their families who looked and dressed as if they were living, not in 1966 really, but the 1940's or 1950's, because except for briefly glimpsed cars and trucks that can be spotted as of the 1960's, the clothes are so drab and traditional they could be from any of three decades. But the reformatted film now looks too pristine to come from anything but the last decade. So the feeling is very strange but compelling, sometimes magical, certainly timeless.

Second, these people are remarkable actors. The story seems artificial, of the period (the 1960's), but with a little of the quality of a fairy tale or legend. It is implausible as realism, despite the extremely naturalistic settings and people. The protagonist isn't a non-pro. Adelino is played by Geraldo Del Rey, the handsome "Brazilian Alain Delon," and feels like a storybook hero. His undying love of Júlia, who has married his brother Raimundo, has the quality of myth. His behavior is unrealistic. He has a mysterious back ailment that cause him to take to bed and sweat copiously, but he does challenging physical work and when in bed with the injured back, tosses and turns, a thing back sufferers wouldn't do.

There is an odd contrast between this doomed love story and the realistic elements, such as the search for work, the clear picture that the Portuguese fishing village of Furadouro to which Adelino has returned is terribly poor. The residents live in houses that are little more than huts; Adelino lives in a structure that's almost like a Native American teepee, made of sticks and straw. Obviously to call this kind of film "an ethnographic portrait" is a misleading simplification. It uses its "ethnographic" elements in a complex and rather mysterious way. In particular, it is hard to tell man times where the story is going, though it always seems sure of itself, and the pacing is sure.

Change of LIfe/Mudar de vida, 90 mins., was shown by Harvard Film Archive and later at Filmforum in Los Angeles in 2012 and also in this new restored digital print at Locarno Sept. 2013. Filmforum provides more complete information, which explains that this was "an important precursor to the radical documentary-shaped fiction of Trás-os-Montes and, much later, the work of Pedro Costa and Miguel Gomes." Screened as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center's Art of the Real series 2014, showing Thursday, April 24 at 9:00pm and Friday, April 25 at 5:00pm at Lincoln Center. Highly recommended.

This film may currently be viewed in its entirety on YouTube, but without subtitles. The image quality is poor (and not the digital restoration with its subtle gray tones) but you can at least appreciate the beautiful mandolin music soundtrack with its fados-like flavor.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 03:14 PM.

-

ACTRESS (Robert Greene 2014)

ROBERT GREENE: ACTRESS (2014)

BRANDY BURRE IN ACTRESS

An former actress dramatizes her own life as a housewife

"This thoroughly compelling and at times thoroughly unnerving new film by Robert Greene (Fake It So Real) is a documentary that feels like intimate melodrama. Brandy Burre had a recurring role on HBO’s The Wire when she gave up her career to start a family. After a few years of life in the country, she decides to return to acting, and sets the denouement of her relationship in motion. As she comes apart on camera in varying shades of drama, it's never clear at what level this film may simply be the next role." So reads the Art of the Real FSLC blurb. But this film is more suitable for a PBS series than a festival, and it is hardly new in any way technically. It very much resembles the famous and pioneering pre-reality show 12-hour 1973 PBS series "An American Family," in which also the parents in question of the Loud family, whose eldest son Lance is openly gay, find their marriage falling apart. Here, Burre's husband, who is poorly depicted in the film, a restauranteur, apparently distant as a husband, if a diligent father to the two small children rarely utters a line on camera. While he and the kids are on a trip visiting his parents, Brandy enjoys her freedom by having a date with an unidentified man in New York City, away from her and her husband's Beacon, New York residence. It is when Brandy's husband discovers this relationship that he decides the marriage is on the rocks and it's time to move out to his own apartment, and there are hints in Brandy's earlier monologues to the camera that love had gone out of the marriage well before this. Descriptions of the film that imply it's Brandy's decision to go back into acting that causes the marriage to disintegrate go against the facts as shown in the film itself.

There is too much pointless use of slow motion in this film, which moves too slowly as it is. The 88 minutes feel like much more. Filming of Brandy's expressed thoughts about getting acting roles and preparations for auditions is needlessly drawn out, and when we expect something to happen, instead, everything stops because Brandy has fallen out of her car and suffered contusions to her eye. Fake It So Real being the director's previous film, about pro wrestlers, the obvious high concept of the film is that Brandy will be self-dramatizing in her "playing" of herself even when engaged in mundane tasks like feeding the children. But it's hard to see anything new in this Whether or not Brandy's tears are exaggerated or not when she recounts moments when her partner first showed he cared more about his restaurant than about her, the sentiments are such as any disappointed woman would express. Obviously the Loud family in "An American Family" in 1973 became "actors" too because cameras were always being trained upon them and their interactions. Actress plays as the closing night film in the Art of the Real 2014 series at Lincoln Center Saturday, April 26 at 8:00pm. Filmmaker Robert Greene and subject Brandy Burre in person for Q&A.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 03:12 PM.

-

BLOODY BEANS (Narimane Mari 2013)

NARIMANE MARI: BLOODY BEANS (2013)

Algerian kids filmed in a poetic reconsideration of poverty and the Algerian war

"A group of Algerian children frolic on the beach, but their roughhousing soon turns into a kind of reenactment of the Algerian War of Independence that plays out as equal parts Lord of the Flies and Les Carabiniers." This is the Lincoln Center Art of the Real series blurb in brief, but if Jay Weissberg's detailed description in Variety is correct, the film has a "performance piece feel" throughout, but is not conceived as a "reenactment" that develops out of "roughhousing." Instead, the bunch of skinny boys (and a few plumper girls) swim in the Mediterranean all day, but when they talk, it vaguely emerges that this is taking place during the time of the Algerian war and is not just a reenactment of it, however symbolic and performance-piece-ish the following action is. This includes a trip to the pig-faced colonial man's house, then a night when the boys paint their bodies and don makes and go through a Christian cemetery to the caserne where they "kidnap" a French guard (played by an actor with an Arab name, though, Samy Bouhouche), dance around with balloons in nice light with nice music, and take him back to the beach, where they make friends with him and dawn breaks. The final sequence shows the boys and girls floating in the calm water and reciting the lines of an Antonin Artaud poem that ends with the question, "Is being better than obeying?" To which the answer is yes.

This is a little film where you have to go with the flow, and the nighttime sequence is a lot more beautiful than anything else, particularly the dancing around with balloons and mock stabbings with paper knives, in which the boys show great spirit and invention and move with balletic grace.

Comparisons with The Lord of the Flies have been made in references to this film, and the boys have been referred to as "feral," but these are misleading exaggerations. Mari doesn't develop a narrative situation complex enough to suggest any alteration in the boys or their having a "society" other than their being pals from poor families who swim at the same beach. Though their families aren't seen, when they complain all the time about eating a diet consisting mainly of beans and sleeping all in one room "like hens," they're saying they have (poor) families they live with normally.

Importantly, the boys are very lively, and their interactions in the water and on the beach and thereafter are very playful, affectionate, and free, and this is the heart of the film's energy and life. Each "child" (as they're called in the credits) has a real complete name but also a nickname, like "Bone Marrow." One of them sings songs, at first an Egyptian love song, later Algerian songs. One is exceptionally tall and scrawny. But they are nearly all skinny, and they are unfortunately not well differentiated either as characters or as physical types as are the characters in William Golding's The Lord of the Rings, and this is a weakness: see them howeer simply as a homogenous group of kids who become an impromptu performance troupe.

I can't improve on Weissberg's concluding lines ending a fine detailed description of Bloody Beans, in which he notes that "intense workshoppping" was importanat in bringing out the best "in the non-pro tyke actors." Indeed as he writes, their "simmering, almost balletic energy drives the rhythms of the film as much as the accomplished editing"; also as he writes, dp Nasser Madjkane's "acive camera practically dances alongside the children" in long takes that hold onto the mood. The music and "curious soundscapes" are extremely important in what becomes an "overall dreamlike picture." Special credit goes to the memorable and original music by Zombie Zombie, Cosmic Neman, and Etienne Jeman; it takes over during the final credits and even after the final credits for a good length of time, and anyone watching the film would be a fool to leave before the last note his sounded. The music is a huge element here but also a thoroughly integral one.

Weissberg notes with disapproval that this film has been "mislabeled a documentary by certain festivals" -- particularly Copenhagen's CPH:DOX, where it won the Best Doc prize. Festivals indeed may need to review their categories, and keep the hybrid categories separate from more informational "documentary" programs in giving out awards. As thisdescription should show, Bloody Beans is an imaginative romp with strong political-historical overtomes using non-actors, and has nothing of he observational recoding documentary about it -- unlike, for example, Paulo Rocha's 1966 Change of LIfe,, also in the Art of the Real series, which makes extensive use of actual milieux of the non-actors incorporated into its story, though it also is not a pure documentary but a fanciful narrative using non-actors, somewhat as in Italian Neorealist films. But the definition of Art of the Real makes clear that it's interested in artful, imaginative boundary-crossers, and Bloody Beans is a perfect example.

Bloody Beans/Loubia hamra ("Red Beans"), 77 mins., was first shown at Marseille, then CPH: DOX and Turin. It was screened for this review as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center's 2014 Art of the Real series, in which it shows Saturday, April 12, 2014 at 9:30pm and Sunday, April 13 at 4:30pm at Lincoln Center. Filmmaker Narimane Mari in person for Q&A at both screenings.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 03:18 PM.

-

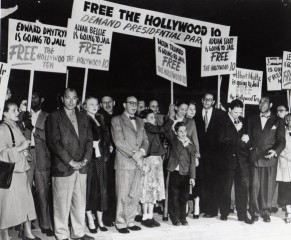

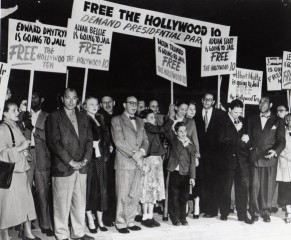

RED HOLLYWOOD (Thom Andersen, Noël Burch 1996)

THOM ANDERSEN, NOËL BURCH: RED HOLLYWOOD (1996)

Reissuing a reassessment of communists in Hollywood

In his original review. film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum described Red Hollywood as "A highly illuminating, groundbreaking, and entertaining video documentary that defies a major taboo in most mainstream writing about current movies.” This film in its remastered and reedited form was shown at the Disney Theater in Los Angeles in January 2014. Thom Anderson is the CalArts film professor known for Los Angeles Plays Itself. He can be counted on for deep knowledge of period Hollywood and an independent point of view. What he and Rosenbaum have in mind is that our perspective on the Hollywood "Red" (Communist) artists blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee is inaccurate, because many of the films they made from the Thirties to the Fifties are denigrated or just forgotten. Film scholars and writers Andersen and Burch, whose documentary is narrated by Billy Woodberry, seek to counter the glib view that of the Hollywood Ten only two had talent and the rest were just unlikeable. To know the forgotten films revisited here is to rethink Hollywood films and perhaps America. These films in a variety of genres raise leading questions about social issues, labor, race, and the Hollywood studio system itself. For students of film and Hollywood an the Forties and Fifties, Red Hollywood is a must-see and contains some invaluable, thought-provoking material. That's not to say it's perfect. It's organization is sometimes puzzling. Sometimes it's hard to see what point is being made.

Red Hollywood is a combination of voiceover narration, talking heads, and film clips from 53 mostly little known films. The speakers included blacklisted writer-filmwriters -- Paul Jarrico, Ring Lardner Jr., Alfred Levitt, and Abraham Polonsky (Polonsky has the last word). The film begins by explaining the historical background, the post-war period, pro-American and pro-Russian propaganda like Paul Jarrico's Song of Russia, the function of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and the Hollywood establishment's cooperation with HUAAC, to ban the Hollywood Ten and others who stood up to the committee's witch hunting. Those who refused to name names or testify to HUAAC were blacklisted; some where able to work again in the Sixties. A lot of clips of Thirties and Forties movies written by communists follow, showing that they didn't mind doing pro-war propaganda, and that Hollywood usually opposed workers' strikes no matter who was writing. It's hard to see what some of these clips add up to, except to a reflection of the times with an American touch, like the family learning about Pearl Harbor and the US delcaring war on Japan while the wife urges her men to come to table "or the roast will get cold." There is typical sentimentalism in the little boy who tells his uncle who's newly out of work that he can "feed" him like his out of work father by asking the butcher for a bone for his dog, then turning it over to him mom to make soup.

The review of films through clips is organized not chronologically but by topics, "myths," "war," "class," "sexes," "hate," "crime," and "death." This doesn't seem the best system. With each new topic there is a return to the Thirties and then the Forties, and some directors and writers are revisited, but no one figure is focused on at length or in depth. Sometimes the point is how communists in film were able to present their own ideas. At other times it seems they did not, or embraced a mainstream view, like opposition to workers' strikes during the War, or pursuit of the War itself. Many of the clips are moments that are very preachy, because they're chosen because they express ideas -- explicitly. Such moments are often the ones that seem the most dated in Hollywood films. It's not so clear that these clips show the Hollywood communist writers had "talent" in a cinematic sense. What is clear is that they may have injected "ideas" into their writing a lot. Perhaps these are intellectual films. But sometimes the "ideas" seem simplistic and crude. And of course, that goes for Hollywood as a whole. In the light of these clips, it seems pushing it on Rosenbaum's part to suggest the films referenced in Red Hollywood may be ground fof constructing "new canons" of cinema, but they do add to our sense of what Thirties and Forties Hollywood movies were like.

Things look up a bit when the documentary switches to the topic of "Sex," showing a teasing scene between a glamorous woman and what seems to be an advertising writer who's turned on by her in John Howard Lawson's Success at Any Price, which the narration says is a writer who was to become a communist willing to indicate the role of class and money in sexual transactions. It's clear the man doesn't think he can afford the woman and she says "I could use you." Whether she actually has a financial advantage over him, however, isn't so clear, from this excerpt anyway.

The film ends with Polansky's reading a climactic scene from Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969), which he co-wrote and directed. It was one of only three films he made, and the first he made after being blacklisted in the late Forties. "Indians don't last in prison. They weren't born for it like the whites..." It's fascinating to see the aging Polansky read the scene, than watch Robert Blake perform it in a clip (one of the few in color). The dialogue may sound artificial, Forties. But how Blake brings it to life! At the end, Polansky declares that the only causes worth fighting for are the lost ones.

Red Hollywood, 120 mins., remastered and reedited, has been shown at a number of venues since its rerelease in 2013. It was screened for this review as part of the Art of the Real series of the Film Society of Lincoln Center. It will be shown in the series Saturday, April 12, 2014 at 6:30pm and Sunday, April 13 at 2pm at Lincoln Center. Filmmaker Thom Andersen in person for Q&A on April 12.

In its earlier form this film is available in it entirety on YouTube.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 02:51 PM.

-

DEAD MAN (Jim Jarmusch 1995)--Permanent Vaction: The Films of Jim Jarmusch (FSLC)

JIM JARMUSCH: DEAD MAN (1995)

Permanent Vacation: The Films of Jim Jarmusch

Film Society of Lincoln Center 2-10 April 2014

JOHNNY DEPP IN THE OPENING TRAIN SEQUENCE OF JARMUSCH'S DEAD MAN

'Dead Man' revisited

"It is preferable not to travel with a dead man," says the Henri Michaux epigraph to Jim Jarmusch's 1995 film. Is it preferable not to watch the film again, having seen and been deeply impressed by it when it opened in America in 1996? Seeing it in Lincoln Center's retrospective makes its trippyness seem even trippier, its hallucinatory strangeness highlighted by the overlapping of memory with how it looks now, highlighting the best and worst of it. It still seems a brilliant vision, a dark masterpiece one would hardly have predicted from the director's first five films. Dead Man is grander than them, and also set in the past. Its elements jar with each other: hallucinatory strangeness, crude, shocking, or gross moments all through; violence mocking gunslinger Westerns; dry jokes; poetry, ritual, myth. If Jarmusch even begins to fit all these together, he's staged one of the great coups of movies of the Nineties. One should begin by just unquestioningly savoring Dead Man's rich strangeness. But eventually on re-watching one ought to be more qualified to say what it all means. But don't forget e.e. cummings' line, "A poem must not mean, but be."

On maybe the simplest level Dead Man is a typical picaresque tale, depicting a meek young character who runs into trouble immediately, has adventures, and somehow survives throughout them -- because William Blake does actually survive for a remarkably long time, given that he is a dead man, from when Charlie Dickenson shoots him and kills his ex-girlfriend Thel Russell (Mili Avital). But William Blake's bad luck, going across the country on his last dollar after spending everything on his parents' funeral, then laughed at and expelled at gunpoint when he presents his letter guarantee of a job, is so black, the story right away is more Kafkaesque than picaresque.

Is it all a nightmare dream? It seems so right from that opening ride on the train, with William Blake of Cleveland (Johnny Depp, looking very young and naive; he will look Indian, slavic, and toughened at the end of things). Around him sit richly tricked out nineteenth century rural characters. Then there is the moment when men open the windows and fire away their rifles at buffalo, because it's government policy to have open season on them (like Indians). Then the train fireman, eyes popping out of his soot-darkened face (the preternaturally strange Crispen Glover) sits and talks to Blake, in his loud plaid suit, clutching his suitcase, wearing his shiny granny glasses. Glover talks dreamy nonsense. He's tripping. But the key words he utters are "hell" -- "What makes you come all the way out here. . . to hell?" And "end of the line." "Machine," the town Blake thinks he's headed to for his job as bookkeeper for the Dickenson factory, is the "end of the line." The message is clear. He's a goner before the opening credits. This opening sequence alone, with its visionary interiors and interrupting tempo shots of wheels and the rising sound of train on track, makes this film classic. There is no other sequence quite like it on film. But, like the lovely transcendental opening of Von Trier's Melancholia, it risks making the rest anticlimactic.

Dead Man is a long slow trip into death, like Thomas Man's Death in Venice or Malcolm Lowry's Under the Volcano. Like Hemingway's "Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" its milquetoast becomes brave, and a calm mensch, and then dies. Not surprisingly, there are bones everywhere, and when William Blake first walks into Machine he sees a wall full of skulls. When his spirit guide, Nobody (Gary Farmer) trips on peyote, he sees Blake's head turn into a white skull.

[img] ......

......

Is it an absurdist hipster romp? Some would say so. And it screams with mocking laughter, like John Hurt's when William Blake insists on going in to speak to the factory owner, Dickenson (Robert Mitchum). Dead Man is, incidentally, a parade of tasty cameos. It's also striking to see how young some of the actors looked then, and how some (Depp) still look much the same and some (Hurt) looked gnarly even then. Most come and go fast. Even the three assassins Dickenson Senior hires to hunt down William Blake for killing his son Charlie (Gabriel Byrne) soon bump each other off or get bumped off. Hence Gary Farmer as Nobody becomes extremely important as the only character/actor (character actor) who runs through to the end, and if you don't like him, you won't like Dead Man. Nobody is jokey, absurd, profound, unclassifiable, like the whole movie. The actor is a Canadian-born Native American, but he is nobody -- nobody's conventional idea of an Indian. He's very wise, but maybe he's a wise fool. It turns out he takes his ritual role as a guide to the mirror world quite seriously.

So then when Nobody brings the by now seriously wounded and clearly dying William Blake by canoe to the Northwest Indian coastal village to place him in a Ship of Death sturdy enough to carry him to the other world, there's no more joking. This may be why this passage is in some ways my least favorite, because by this time the film has gone on a little bit too long, its hypnotically slow pacing has begun to catch up with it (despite the energy provided by the throbbing, haunting rhythm of Neil Young's guitar, a musical motif that's one of Dead Man's most defining elements). And there is something a little too gray about this last section, just as some of the earlier woods scenes are a little too dark. Let's not forget, though, that Jarmusch and his dp, Dutch Wim Wenders regular Robby Müller, are providing some of the freshest images of the Wild West we've ever seen, both avoiding and mocking cliché.

Maybe it's obvious why a lot of people never seem to "get" Jarmusch, if you can say Dead Man is his "most conventional film," yet it's somehow such a mishmash of elements and tones you may need to be an aficionado to appreciate it. The Metacritic rating is 58%. "Come back, Jim Jarmusch. Come back to the pungency of your first films. Leave the 1970s. Come back to the future," wrote Stanley Kaufman in The New Republic. And Stephen Holden of the New York Times said "The film's energy begins to flag after less than an hour, and as its pulse slackens it turns into a quirky allegory, punctuated with brilliant visionary flashes that partially redeem a philosophic ham-handedness." Maybe so, but note well that there are some important raves in Metacritic's list, one at the top from no less an authority than Jonathan Rosenbaum, who classified it in The Chicago Reader as a "masterpiece." But I became personally aware of Jarmusch's tricky status when I loved his recent The Limits of Control (and called it the best thing he's done since Dead Man), but could find only two or three favorable reviews of it.

Dead Man, 121 mins., debuted at Cannes in May 1995, when it was nominated for the Palme d'Or. It opened in US cinemas 10 May 1996, when this reviewer saw it at the Paris Theater on 57th Street in New York just back from a hallucinatory journey of his own. Screened for this review for the second time 18 years later as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center's retrospective, Permanent Vacation: The Films of Jim Jarmusch, May 2-10, 2014. It shows Saturday, 5 April 2014 at 9:00pm, Sunday, 6 April at 1:15 pm, Wed. 9 April at 6:30 pm, and Thurs., 10 April at 3:45 pm. Shown with Jarmusch's music video for Neil Young's "Dead Man Score" (5 mins.).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 02:49 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

......

......

Bookmarks